Aquatektur – Japan 2008 Aquatektur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archi-Ne Ws 2/20 17

www.archi-europe.com archi-news 2/2017 BUILDING AFRICA EDITO If the Far East seems to be the focal point of the contemporary architectural development, the future is probably in Africa. Is this continent already in the line 17 of vision? Many European architects are currently building significant complexes: 2/20 the ARPT by Mario Cucinella, the new hospital in Tangiers by Architecture Studio or the future urban development in Oran by Massimiliano Fuksas, among other projects. But the African architectural approach also reveals real dynamics. This is the idea which seem to express the international exhibitions on African architecture during these last years, on the cultural side and architectural and archi-news archi-news city-panning approach, as well as in relation to the experimental means proposed by numerous sub-Saharan countries after their independence in the sixties, as a way to show their national identity. Not the least of contradictions, this architecture was often imported from foreign countries, sometimes from former colonial powers. The demographic explosion and the galloping city planning have contributed to this situation. The recent exhibition « African Capitals » in La Villette (Paris) proposes a new view on the constantly changing African city, whilst rethinking the evolution of the African city and more largely the modern city. As the contemporary African art is rich and varied – the Paris Louis Vuitton Foundation is presently organizing three remarkable exhibitions – the African architecture can’t be reduced to a single generalized label, because of the originality of the different nations and their socio-historical background. The challenges imply to take account and to control many parameters in relation with the urbanistic pressure and the population. -

A Humanist Approach to Tropical High-Rise a Centre for Urban Greenery and Ecology Publication 131

COMMENTARY CITYGREEN #7 130 Tall Buildings in Southeast Asia: A Humanist Approach to Tropical High-Rise A Centre for Urban Greenery and Ecology Publication 131 WOHA aims to transform and adapt vernacular and passive responses to the climate into the high-rise form and contemporary technologies, while creating comfort without the need for mechanical systems. High-rise, high-density living has been embraced as a positive accom- tures that jostle for height, status, and domination of nature through modation solution for many millions of people living in Asia’s growing technology. Inhabitants of these aggressive structures take pleasure urban metropolis. WOHA Architects has designed a series of build- in the high status of these glossy technological marvels. ings for Southeast Asia that expand the way high-rise, high-density living is conceived. Approaching the design from lifestyle, climate The emphasis in WOHA’s high-rise projects has been on the individual, and passive energy strategies, the towers are radical yet simple and on human scale, on choice, on comfort, on opening up to the climate, show that the tall building form can be expanded in many directions. on community spaces, and on nature. The mild environment of Singa- Located in Singapore, which has been the laboratory for much of its pore allowed these concerns to take priority over the typical shapers design research, WOHA articulates its approach to design, using both of the high-rise form. Through careful balancing of developers’ needs built and unbuilt projects as illustrations, in this paper. and end-user amenity, WOHA has managed to incorporate these values into projects with standard developer budgets. -

Tall Buildings in Southeast Asia - a Humanist Approach to Tropical High- Rise

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Tall Buildings in Southeast Asia - A Humanist Approach to Tropical High- Rise Authors: Mun Summ Wong, Founding Partner, WOHA Architects Richard Hassell, Founding Partner, WOHA Architects Subjects: Architectural/Design Social Issues Keywords: Climate Human Comfort Social Interaction Sustainability Publication Date: 2009 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal, 2009 Issue III Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Mun Summ Wong; Richard Hassell Tall Buildings in Southeast Asia - A Humanist Approach to Tropical High-rise "Much of the developing world is located around the equatorial belt, and it is vital that tropical design research addresses the important Mun Summ Wong Richard Hassell questions of how we can live well and Authors sustainably with our climate and with the Mun Summ Wong, Founding Partner, WOHA e: [email protected] densities projected for the rapidly growing Richard Hassell, Founding Partner, WOHA e: [email protected] region." WOHA 29 Hong Kong Street Singapore 059668 t: 65 6423 4555 High-rise, high-density living has been embraced as a positive accommodation solution for f: 65 6423 4666 many millions of people living in Asia’s growing urban metropolis. This paper outlines a Mun Summ Wong & Richard Hassell number of high rise case studies designed by a Singapore-based architectural practice (WOHA Wong Mun Summ and Richard Hassell are co-founding Architects) who have designed a series of buildings for South-East Asia that expand the way directors of WOHA, a regional design practice based in Singapore. -

Ryuichi Sakamoto Merry Christmas Mr

Ryuichi Sakamoto Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Stage & Screen Album: Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence Country: UK Released: 1988 Style: Soundtrack, Downtempo MP3 version RAR size: 1633 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1391 mb WMA version RAR size: 1695 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 573 Other Formats: XM AHX VOX WAV AAC DTS TTA Tracklist Hide Credits Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence A1 4:34 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Batavia A2 1:18 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Germination A3 1:47 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* A Hearty Breakfast A4 1:21 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Before The War A5 2:14 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* The Seed And The Sower A6 5:00 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* A Brief Encounter A7 2:23 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Ride, Ride, Ride (Celliers' Brother's Song) A8 1:03 Composed By – S. McCurdy* The Fight A9 1:29 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Father Christmas B1 2:00 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Dismissed! B2 0:10 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Assembly B3 2:16 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Beyond Reason B4 2:01 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Sowing The Seed B5 1:53 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* 23rd Psalm B6 2:00 Written-By – Trad.* Last Regrets B7 2:40 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Ride, Ride, Ride (Reprise) B8 1:04 Composed By – S. McCurdy* The Seed B9 1:02 Composed By – R. Sakamoto* Forbidden Colours B10 4:42 Composed By – D. Sylvian / R. Sakamoto*Vocals – David Sylvian Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – National Film Trustee Company Ltd. Copyright (c) – Virgin Records Ltd. -

Bjarke Ingels Group WEWORK SCHOOL, NEW YORK, USA

Gople Bjarke Ingels Group WEWORK SCHOOL, NEW YORK, USA Architectural Project: WeWork & BIG Photo: Dave Burk 3 GOPLE LAMP 4 BJARKE INGELS GROUP BJARKE INGELS GROUP BIG is a group of architects, designers and thinkers operating within innovative as they are cost and resource conscious, incorporating the fields of architecture, urbanism, research and development with overlapping design disciplines for a new paradigm in architecture. offices in Copenhagen and New York City. BIG has created a reputation BIG believe strongly in research as a design tool. for completing buildings that are as programmatically and technically 5 GOPLE LAMP 6 DESIGNERS MURANO GLASS A powerful LED light source is housed within a handblown glass diffuser, produced according to ancient Venetian glass-blowing techniques and created in Murano. The soft glass helps diffuse a soft glow, as light fills the pill shaped diffuser. The diffuser is available in three options: crystal glass with a white gradient, transparent glass with a silver or copper metallic finish. 7 GOPLE LAMP 8 BJARKE INGELS GROUP THE HUMAN LIGHT Gople Lamp is the perfect example of Artemide’s guiding philosophy of “The Human Light”. It aspires to create light that is good for the wellness of man and for the environment that has a positive impact on our quality of life. 9 GOPLE LAMP 10 BJARKE INGELS GROUP SAVOIR FAIRE The human and responsible light goes hand in hand with design and material savoir faire, combining next-generation technology with ancient techniques. It is a perfect expression of sustainable design. BIG OFFICES, COPENHAGEN, DENMARK Architectural Project: Offices 11 GOPLE LAMP 12 BJARKE INGELS GROUP WELLNESS The end result is a product that delivers both visual comfort and aesthetic value, while contributing to the wellness of both man and the environment. -

Table of Contents

CITYFEBRUARY 2013 center forLAND new york city law VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1 Table of Contents CITYLAND Top ten stories of 2012 . 1 CITY COUNCIL East Village/LES HD approved . 3 CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CPC’s 75th anniversary . 4 Durst W . 57th street project . 5 Queens rezoning faces opposition . .6 LANDMARKSFPO Rainbow Room renovation . 7 Gage & Tollner change denied . 9 Bed-Stuy HD proposed . 10 SI Harrison Street HD heard . 11 Plans for SoHo vacant lot . 12 Special permits for legitimate physical culture or health establishments are debated in CityLand’s guest commentary by Howard Goldman and Eugene Travers. See page 8 . Credit: SXC . HISTORIC DISTRICTS COUNCIL CITYLAND public school is built on site. HDC’s 2013 Six to Celebrate . 13 2. Landmarking of Brincker- hoff Cemetery Proceeds to Coun- COURT DECISIONS Top Ten Stories Union Square restaurant halted . 14. cil Vote Despite Owner’s Opposi- New York City tion – Owner of the vacant former BOARD OF STANDARDS & APPEALS Top Ten Stories of 2012 cemetery site claimed she pur- Harlem mixed-use OK’d . 15 chased the lot to build a home for Welcome to CityLand’s first annual herself, not knowing of the prop- top ten stories of the year! We’ve se- CITYLAND COMMENTARY erty’s history, and was not compe- lected the most popular and inter- Ross Sandler . .2 tently represented throughout the esting stories in NYC land use news landmarking process. from our very first year as an online- GUEST COMMENTARY 3. City Council Rejects Sale only publication. We’ve been re- Howard Goldman and of City Property in Hopes for an Eugene Travers . -

Enjoying the Outdoors Since 1947 Vestre of Norway Presents Street Furniture with Emphasis on Quality, Innovation and Function

VESTRE AT CLERKENWELL DESIGN WEEK 2014 Enjoying the outdoors since 1947 Vestre of Norway presents street furniture with emphasis on quality, innovation and function. The design is rooted in the principle of the Scandinavian aesthetic: products that are accessible and available to everyone. DATE: 20-22 MAY 2014 POP-UP EXHIBITION LOCATION: ST JAMES’ CHURCH GARDEN, CLERKENWELL CLOSE, LONDON EC1R 0EA Vestre invites you to visit our exhibition at the historic Clerkenwell site, which is the perfect venue to exhibit Vestre’s collection of street furniture and to enjoy the outdoors. We are delighted to announce that we will be serving genuine Scandinavian outdoor lunches. Vestre’s furniture is intended to bring something unique to, and cope with use in, the urban streetscape. It has to be usable summer and winter, year after year. This challenges the designer to create furniture that is not only timelessly elegant, but sufficiently strong and durable too. “The quality requirements for our furniture are tough and uncompromising, but not at the expense of innovative, playful design,” says CEO Jan Christian Vestre. He stresses how important it is to try out new concepts and a selection of this year’s news is part of the pop-up exhibition at Clerkenwell Design Week 2014: • Vestre BUZZ is a retro futuristic-inspired bench and table in circular form. • Vestre MOVE is a bench inspired by motion that is an invitation to take a welcome breather. • Vestre BLOC sun bench adds something more to a seating area: a place to Contacts: sit and be while soaking up some sun. -

Mountain Dwellings: Category Winner of World Architecture Festival 2008

Mountain Dwellings: Category Winner of World Architecture Festival 2008 Looking at the splendid photos of this building, what would you imagine? Is it a public building or a residential building? Or else? Named as Mountain Dwellings, this building is located in the Orestad, 33.000 m2, a new urban development in Copenhagen, Denmark. It contains housing (1/3)and parking (2/3) in combining successfully the splendours of the suburban backyard with the social intensity of urban density. Its visual appearance is stunning. The nice architecture design and success construction have enabled it to be the Category Winner of World Architecture Festival 2008 (http://www.worldbuildingsdirectory.com/project.cfm?id=755). What makes this project comfortable for living is that the parking area is connected to the street, and all apartments have roof gardens facing the sun, amazing views and parking on the 10th floor. The Mountain Dwellings appear as a suburban neighbourhood of garden homes, floating over a 10-storey building - suburban living with urban density. The residents of the 80 apartments will be the first in Orestaden to have the possibility of parking directly outside their homes. The gigantic parking area contains 480 parking spots and a sloping elevator that moves along the mountain’s inner walls. In some places the ceiling height is up to 16 meters which gives the impression of a cathedral-like space. The color design from facade to floor during the day and during the night makes the building unique from architectural point of view. Sika contributed in the decorative colour design of Mountain Dwellings. -

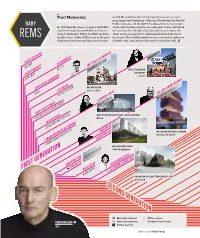

First Generation Second Generation

by Paul Makovsky world. Not only has the firm designed some of our era’s most important buildings—Maison à Bordeaux, the Seattle BABY Public Library, and the CCTV headquarters, to name just In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia a few—but its famous hothouse atmosphere has cultivated and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon VriesenVriesen-- the talents of hundreds of gifted architects. Look at the dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan chart on these pages: it is a distinguished architectural REMS Architecture. Today OMA is one of the most fraternity. These OMA grads have now created an influence influential architectural practices in the all their own, and they are the ones to watch in 2011. P ZAHA HADID RIENTS DIJKSTRA EDZO BINDELS MAXWAN MATTHIAS SAUERBRUCH WEST 8 SAUERBRUCH HUTTON EVELYN GRACE ACADEMY CHRISTIAN RAPP London RAPP + RAPP CHRISTOPHE CORNUBERT M9 MUSEUM LUC REUSE Venice, Italy WILLEM JAN NEUTELINGS PUSH EVR ARCHITECTEN NEUTELINGS RIEDIJK LAURINDA SPEAR ARQUITECTONICA KEES CHRISTIAANSE SOUTH DADE CULTURAL ARTS CENTER KGAP ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS Miami YUSHI UEHARA ZERODEGREE ARCHITECTURE MVRDV WINY MAAS MUSEUM AAN DE STROOM Antwerp, Belgium RUURD ROORDA KLAAS KINGMA JACOB VAN RIJS KINGMA ROORDA ARCHITECTEN BALANCING BARN Suffolk, England FOA WW ARCHITECTURE SARAH WHITING FARSHID MOUSSAVI RON WITTE FIRST GENERATION MIKE GUYER ALEJANDRO ZAERA POLO GIGON GUYER MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART Cleveland SECOND GENERATION Married/partnered Office closed REM KOOLHAAS P Divorced/separated P Pritzker Prize laureate OMA Former partner Illustration by Nikki Chung REM_Baby REMS_01_11_rev.indd 1 12/16/10 7:27:54 AM BABY REMS by Paul Makovsky In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesen- dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture. -

Generali Real Estate and Citylife Presented the New Project

The new gateway to CityLife Air, light, greenery and open spaces: a project designed for people and the city The global studio BIG-BJARKE INGELS GROUP has designed the new project Milan, 15 November 2019 - CityLife today presented the new project that marks the start of the district completion phase and that will create a new gateway to CityLife and the city. Selected following an international competition between major design and architectural studios, the project was created by the studio BIG - Bjarke Ingels Group. The project envisages the creation of two buildings joined by a roof with an urban-scale portico that, framing the three existing towers without reaching their height, will create a new gateway to CityLife from Largo Domodossola through an extensive green area that will further enrich the liveability of the district and constitute a new aspect of restoration for the City of Milan. A project designed for people that creates a bridge between private and public spaces. The roof will not only be an element forming a structural connection between the two buildings, but will also create a shaded public realm activated by street furniture and green spaces that can be used year-round. The architectural intervention was designed to open up and fully integrate the district, starting from the existing space and context. The new CityLife gateway will be integrated with the urban areas, the streets and the existing road network, creating a continuum between the district and the city. The new building will stand on an area of around 53,000 square metres (GFA) more than 200 metres long, with a characteristic portico structure that will be 18 metres wide at its narrowest point. -

ANNEX C: Factsheet on Team Members Behind the Singapore Pavilion Architecture & Creative Direction WOHA Architects WOHA

ANNEX C: Factsheet on team members behind the Singapore Pavilion Architecture & WOHA Architects Creative Direction WOHA was founded by Wong Mun Summ and Richard Hassell in 1994. The Singapore-based practice focuses on researching and innovating integrated architectural and urban solutions to tackle the problems of the 21st century such as climate change, population growth and rapidly increasing urbanisation. WOHA has accrued a varied portfolio of work and is known for its distinct approach to biophilic design and integrated landscaping. The practice applies their systems thinking approach to architecture and urbanism in their building design as well as their regenerative masterplans. Their rating system to measure the performance of buildings, as laid out in their book “Garden City Mega City”, has garnered interest internationally and is being adopted into construction policies in several cities. WOHA has received a number of architectural awards such as the Aga Khan Award for One Moulmein Rise as well as the RIBA Lubetkin Prize and International Highrise Award for The Met. The practice won the 2019 CTBUH 2019 Urban Habitat and Best Mixed-Use Building, 2018 World Architecture Festival World Building of the Year for Kampung Admiralty, and 2018 CTBUH Best Tall Building Worldwide for the Oasia Hotel Downtown. The practice currently has projects under construction in Singapore, Australia, China and other countries in South Asia. Visit www.woha.net for more information. Project Radius Experiential International Management One of the forerunners in providing experiential marketing solutions, Radius was founded in Singapore in 1997 and has since delivered 3,000 innovative and integrated marketing solutions globally. -

Good Design 2018 Awarded Product Designs and Graphics and Packaging

GOOD DESIGN 2018 AWARDED PRODUCT DESIGNS AND GRAPHICS AND PACKAGING THE CHICAGO ATHENAEUM: MUSEUM OF ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN THE EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURE ART DESIGN AND URBAN STUDIES ELECTRONICS 2018 File Number7669 Google Pixel 2, 2017 Designers: Google Hardware Design Team, Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA Manufacturer: Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA File Number7671 Google Pixelbook and Pen, 2017 Designers: Google Hardware Design Team, Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA Manufacturer: Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USAs File Number7672 Daydream View, 2017 Designers: Google Hardware Design Team, Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA Manufacturer: Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA File Number7673 Google Home, 2017 Designers: Google Hardware Design Team, Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA Manufacturer: Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA File Number7674 Google Home Mini, 2017 Designers: Google Hardware Design Team, Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA Manufacturer: Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA File Number7675 Google Home Max, 2017 Designers: Google Hardware Design Team, Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA Manufacturer: Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA File Number7676 Google Pixel Buds, 2017 Designers: Google Hardware Design Team, Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA Manufacturer: Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA File Number7677 Google Clips, 2017 Designers: Google Hardware Design Team, Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA Manufacturer: Google LLC., Mountain View, California, USA File Number7685 HP Omen X 17, 2016-2017 Designers: HP Inc., Houston, Texas, USA Manufacturer: HP Inc., Houston, Texas, USA Good Design Awards 2018 Page 1 of 77 December 10, 2018 © 2018 The Chicago Athenaeum - Use of this website as stated in our legal statement.