Growth of Modern Education Under Hereditary Monarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographical and Historical Background of Education in Bhutan

Chapter 2 Geographical and Historical Background of Education in Bhutan Geographical Background There is a great debate regarding from where the name of „Bhutan‟ appears. In old Tibetan chronicles Bhutan was called Mon-Yul (Land of the Mon). Another theory explaining the origin of the name „Bhutan‟ is derived from Sanskrit „Bhotanta‟ where Tibet was referred to as „Bhota‟ and „anta‟ means end i. e. the geographical area at the end of Tibet.1 Another possible explanation again derived from Sanskrit could be Bhu-uttan standing for highland, which of course it is.2 Some scholars think that the name „Bhutan‟ has come from Bhota (Bod) which means Tibet and „tan‟, a corruption of stan as found in Indo-Persian names such as „Hindustan‟, „Baluchistan‟ and „Afganistan‟etc.3 Another explanation is that “It seems quite likely that the name „Bhutan‟ has come from the word „Bhotanam‟(Desah iti Sesah) i.e., the land of the Bhotas much the same way as the name „Iran‟ came from „Aryanam‟(Desah), Rajputana came from „Rajputanam‟, and „Gandoana‟ came from „Gandakanam‟. Thus literally „Bhutan‟ means the land of the „Bhotas‟-people speaking a Tibetan dialect.”4 But according to Bhutanese scholars like Lopen Nado and Lopen Pemala, Bhutan is called Lho Mon or land of the south i.e. south of Tibet.5 However, the Bhutanese themselves prefer to use the term Drukyul- the land of Thunder Dragon, a name originating from the word Druk meaning „thunder dragon‟, which in turn is derived from Drukpa school of Tibetan Buddhism. Bhutan presents a striking example of how the geographical setting of a country influences social, economic and political life of the people. -

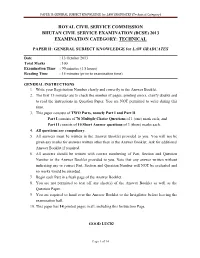

Technical Paper II –

PAPER II: GENERAL SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE for LAW GRADUATES (Technical Category) ROYAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION BHUTAN CIVIL SERVICE EXAMINATION (BCSE) 2013 EXAMINATION CATEGORY: TECHNICAL PAPER II: GENERAL SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE for LAW GRADUATES Date : 13 October 2013 Total Marks : 100 Examination Time : 90 minutes (1.5 hours) Reading Time : 15 minutes (prior to examination time) GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS 1. Write your Registration Number clearly and correctly in the Answer Booklet. 2. The first 15 minutes are to check the number of pages, printing errors, clarify doubts and to read the instructions in Question Paper. You are NOT permitted to write during this time. 3. This paper consists of TWO Parts, namely Part I and Part II. Part I consists of 70 Multiple Choice Questions of 1 (one) mark each; and Part II consists of 10 Short Answer questions of 3 (three) marks each. 4. All questions are compulsory. 5. All answers must be written in the Answer Booklet provided to you. You will not be given any marks for answers written other than in the Answer Booklet. Ask for additional Answer Booklet if required. 6. All answers should be written with correct numbering of Part, Section and Question Number in the Answer Booklet provided to you. Note that any answer written without indicating any or correct Part, Section and Question Number will NOT be evaluated and no marks would be awarded. 7. Begin each Part in a fresh page of the Answer Booklet. 8. You are not permitted to tear off any sheet(s) of the Answer Booklet as well as the Question Paper. -

West Bohemian Historical Review VIII 2018 2 | |

✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ West Bohemian Historical Review VIII 2018 2 | | Editors-in-Chief LukášNovotný (University of West Bohemia) Gabriele Clemens (University of Hamburg) Co-editor Roman Kodet (University of West Bohemia) Editorial board Stanislav Balík (Faculty of Law, University of West Bohemia, Pilsen, Czech Republic) Gabriele Clemens (Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) Radek Fukala (Faculty of Philosophy, J. E. PurkynˇeUniversity, Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic) Frank Golczewski (Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) Michael Gehler (Faculty of Educational and Social Sciences, University of Hildesheim, Hildesheim, Germany) László Gulyás (Institute of Economy and Rural Development, University of Szeged, Szeged, Hungary) Arno Herzig (Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) Hermann Joseph Hiery (Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany) Václav Horˇciˇcka (Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) Drahomír Janˇcík (Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) ZdenˇekJirásek (Faculty of Philosophy and Sciences, Silesian University, Opava, Czech Republic) ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ ✐ Bohumil Jiroušek (Faculty of Philosophy, University of South Bohemia, Ceskéˇ Budˇejovice,Czech Republic) Roman Kodet (Faculty of Arts, University of West Bohemia, Pilsen, Czech Republic) Martin Kováˇr (Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) Hans-Christof Kraus (Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Passau, -

A Historical Background of the Chhoetse Penlop∗ Dorji Wangdi+

A Historical Background of the Chhoetse Penlop∗ Dorji Wangdi+ The institution of the Chhoetse Penlop (later called Trongsa Penlop) is more than 350 years. It was started by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in 1647 after he appointed Chhogyel Minjur Tenpa as his representative in Trongsa. This royal institution with a unique blend of mythology and history represents Bhutan’s past. The Trongsa Dzong was founded by Yongzin Ngagi Wangchuk (1517-1554), the son of Lam Ngawang Chhoejay. According to the legend, Ngagi Wangchuk was guided in a vision by Palden Lhamo, the guardian deity of the Dragon Kingdom, to go to a place in central Bhutan which resembled a bow and which was abundant in food grains (mang-dru). The name Mangdey has its origin in this word. Accordingly, Pal Ngagi Wangchuk arrived at Trongsa in 1541 where he took residence in the village of Yueli which was located on the northern hill-slopes overlooking the then bare hillock upon which the Trongsa Dzong is presently located. One night when Pal Ngagi Wangchuk was meditating in Yueli, his attention was drawn by a flicker of light, resembling that of a butter-lamp burning in the open air, at the spot where the present day Goenkhang in the Trongsa Dzong is located. Upon visiting the spot, he was deeply overwhelmed by discovery of Lhamoi Latsho (a sacred lake of Palden Lhamo) and the hoof prints of Palden Lhamo’s steed. In 1543, Pal Ngagi Wangchuk established a small tshamkhang (meditation quarter) in the sacred spot brought ∗ This is a longer version of the paper printed in Kuensel, Vol XIX No. -

Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics the History of Institutional Change in the Kingdom of Bhutan: a Tale O

Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics The History of Institutional Change in the Kingdom of Bhutan: A Tale of Vision, Resolve, and Power by Marian Gallenkamp Working Paper No. 61 April 2011 South Asia Institute Department of Political Science Heidelberg University HEIDELBERG PAPERS IN SOUTH ASIAN AND COMPARATIVE POLITICS ISSN: 1617-5069 About HPSACP This occasional paper series is run by the Department of Political Science of the South Asia Institute at the University of Heidelberg. The main objective of the series is to publicise ongoing research on South Asian politics in the form of research papers, made accessible to the international community, policy makers and the general public. HPSACP is published only on the Internet. The papers are available in the electronic pdf-format and are designed to be downloaded at no cost to the user. The series draws on the research projects being conducted at the South Asia Institute in Heidelberg, senior seminars by visiting scholars and the world-wide network of South Asia scholarship. The opinions expressed in the series are those of the authors, and do not represent the views of the University of Heidelberg or the Editorial Staff. Potential authors should consult the style sheet and list of already published papers at the end of this article before making a submission. Editor Subrata K. Mitra Deputy Editors Jivanta Schöttli Siegfried O. Wolf Managing Editor Radu Carciumaru Editorial Assistants Dominik Frommherz Kai Fabian Fürstenberg Editorial Advisory Board Mohammed Badrul Alam Barnita Bagchi Dan Banik Harihar Bhattacharyya Mike Enskat Alexander Fischer Karsten Frey Partha S. -

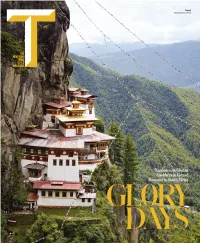

A Cultural and Historical Adventure: Hiking in Vietnam and Bhutan October 8-22, 2018

In Partnership with Asia Academic Experience, LLC A CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL ADVENTURE: HIKING IN VIETNAM AND BHUTAN OCTOBER 8-22, 2018 Ann Highum and Jerry Freund are ready to travel again with a group of adventuresome and curious people, in 2018. They are anxious to share their love for SE Asia and its people, culture, history and natural beauty. Bhutan and Vietnam are fascinating countries--safe for travel, culturally fascinating, and historically important. Bhutan, famous for its “happiness index” has been open for tourism for many years, but not so welcoming. They are working to change that, and since their tourism industry is now highly regulated and well managed, our colleague Lana has negotiated a fascinating tour. It is a privilege to have the opportunity to offer this tour to hardy souls who want a unique adventure in both the northern part of Vietnam and then in Bhutan. There will, of course, be a focus on learning on this tour, with local guest speakers and excellent local guides who will share their knowledge about each country with the group. The tour is also based on taking hikes in remarkable areas, interacting with different ethnic tribes to learn about their customs and cultures, staying in guesthouses in small villages, and experiencing each country more fully than is possible in other tours. It is important to note that many of the hiking experiences will involve uneven terrain, long uphill climbs and up to 7 miles per hike. Altitude is also a factor, although the highest areas we would visit are in the range of 7-8000 feet. -

In Pursuit of Happiness, Bhutan Opens to Globalization and Business

In Pursuit of Happiness, Bhutan Opens to Globalization and Business Kimberly A. Freeman, Ph.D. Mercer University Katherine C. Jackson Mercer University ABSTRACT The Kingdom of Bhutan, a small country situated on the border between China and India, has in recent years become a constitutional democratic monarchy. As part of its 2008 constitution, Bhutan committed to promote conditions that would enable the pursuit of Gross National Happiness. The country thus initiated an effort to improve the quality of life and happiness for its citizens and has embraced globalization far more than previously through attracting business, tourism, and communications. The author’s herein address some of the initiatives provide the context within which these efforts have arisen. Keywords: Bhutan; Gross National Happiness (GNH); Globalization; Constitutional democratic monarchy 1. Introduction In 2006, the 4th King of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, decided he wanted to open Bhutan up to the world and usher in modernization. Forty years ago, in 1972, Bhutan’s fourth king stated that “Bhutan should pursue Gross National Happiness (GNH) rather than Gross National Product (GNP)…with an emphasis not only on economic growth, but also on culture, mental health, social values, compassion, and community” (Sachs, 2011, p. 2) He chose to abdicate the throne to his eldest son and announced Bhutan would hold its first general elections in 2008. His son, King Jigme Khesar Namgyal Wangchuck, took the throne of the new democratic Bhutan on December 14, 2006. Jigme Yoser Thinley was elected prime minister in the election, and Bhutan’s constitution was ratified on July 18, 2008. The concept of GNH has a very long history in Bhutan. -

Pdf Banco Mundial

Estudios de Asia y África ISSN: 0185-0164 ISSN: 2448-654X El Colegio de México A.C. Rodríguez-Calles, Luis Breve historia de Bután. Una identidad y un horizonte común en torno a la felicidad como objetivo político Estudios de Asia y África, vol. 54, núm. 2, Mayo-Agosto, 2019, pp. 373-390 El Colegio de México A.C. DOI: 10.24201/eaa.v54i2.2434 Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=58660239007 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto ESTUDIOS DE ASIA Y ÁFRICA, VOL. 54, NÚM. 2 (169), 2019, PP. 373-390 ISSN 0185-0164 e-ISSN 2448-654X CULTURA Y SOCIEDAD https://dx.doi.org/10.24201/eaa.v54i2.2434 Breve historia de Bután. Una identidad y un horizonte común en torno a la felicidad como objetivo político A brief history of Bhutan. An identity and a common horizon around happiness as a political objective LUIS RODRÍGUEZ-CALLES* Resumen: Se hace un repaso histórico de los acontecimientos más re- levantes ocurridos en el territorio que ahora pertenece a Bután, en el periodo que llega a la instauración de una monarquía hereditaria a principios de siglo XX. En un cuadro se resumen esos acontecimien- tos. Así se pretende dar luz al periodo histórico más desconocido del país con objeto de complementar otros análisis académicos sobre la felicidad, el budismo y las particularidades del modelo de desarrollo en Bután. -

The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch 'Where is Bhutan?': The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N. This journal article has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form, subsequent to peer review and/or editorial input by Cambridge University Press in the Journal of Asian Studies. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press, 2021 The final definitive version in the online edition of the journal article at Cambridge Journals Online is available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911820003691 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Manuscript ‘Where is Bhutan?’: The Production of Bhutan’s Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Abstract In this paper, I interrogate the exhaustive ‘inbetweenness’ through which Bhutan is understood and located on a map (‘inbetween India and China’), arguing that this naturalizes a contemporary geopolitics with little depth about how this inbetweenness shifted historically over the previous centuries, thereby constructing a timeless, obscure, remote Bhutan which is ‘naturally’ oriented southwards. I provide an account of how Bhutan’s asymmetrical inbetweenness construction is nested in the larger story of the formation and consolidation of imperial British India and its dissolution, and the emergence of post-colonial India as a successor state. I identify and analyze the key economic dynamics of three specific phases (late 18th to mid 19th centuries, mid 19th to early 20th centuries, early 20th century onwards) marked by commercial, production, and security interests, through which this asymmetrical inbetweenness was consolidated. -

Stone Inscriptions: an Early Written Medium in Bhutan and Its Public Uses

Stone Inscriptions: An Early Written Medium in Bhutan and its Public Uses Dr. John Ardussi∗ Historical Background Public culture in Bhutan has since the earliest historical times revolved around community life and religion. The two were interlinked in Buddhist teachings brought to Bhutan from Tibet by monks in search of converts in what were once wilderness areas of the Himalayas. The 13th and 14th centuries saw periodic episodes of civil warfare in Central Tibet, sparked off by the inroads and depredations of the Mongols from Central Asia. Many Tibetan monks viewed these events as the culmination of prophecies urging men of religion to flee to so-called Beyul, or serene Hidden Lands along the Himalayan fringe, of which a few were rumored to exist in Bhutan. However Bhutan in those days was not the idyllic place of these men’s imaginations. Their biographies show that upon arrival, they found Bhutan to be a rather rough, illiterate and rural culture, full of dangers. Hence they employed the teaching of Buddhism as a tool to ‘pacify’ the land and people. For example, the famous Tibetan Drukpa monk named Lorepa came to Bumthang in 1248 AD. There, he addressed a crowd of 2,800 people whom he described as “beastlike” (dud ’gro dang ’dra ba), “wild, and temperamental” (rgod-gtum-po).1 The local people were said to be fond of eating meat and sacrificing animals. One century later, the Tibetan Kagyudpa monk named Choeje Barawa fled to Bhutan from the civil disorders in his native homeland of Gtsang, as described in one of his religious songs: ∗ Independent Scholar, CNRS – Paris; Kansas, USA. -

Higher-State-Of-Being-Full-Lowres.Pdf

HIGHER STIn the vertiginousAT mountainsE of Bhutan, where happiness is akin to holiness, bicycling has become much more than a national pastime. It’s a spiritual journey. BY JODY ROSEN OF BEINPHOTOGRAPHSG BY SIMON ROBERTS N BHUTAN, THERE IS A KING who rides a bicycle up and down the mountains. Like many stories you will hear in this tiny Himalayan nation, it sounds like a fairy tale. In fact, itís hard news. Jigme Singye IWangchuck, Bhutanís fourth Druk Gyalpo, or Dragon King, is an avid cyclist who can often be found pedaling the steep foothills that ring the capital city, Thimphu. All Bhutanese know about the kingís passion for cycling, to which he has increasingly devoted his spare time since December 2006, when he relinquished the crown to his eldest son. In Thimphu, many tell tales of close encounters, or near-misses ó the time they pulled over their car to chat with the bicycling monarch, the time they spotted him, or someone who looked quite like him, on an early-morning ride. If you spend any time in Thimphu, you may soon find yourself scanning its mist-mantled slopes. That guy on the mountain bike, darting out of the fog bank on the road up near the giant Buddha statue: Is that His Majesty? SOUL CYCLE The fourth king is the most beloved figure in A rider in the Tour of the Dragon, a modern Bhutanese history, with a biography 166.5-mile, one-day that has the flavor of myth. He became bike race through the mountains of Bhutan, Bhutanís head of state in 1972 when he was just alongside the Druk 16 years old, following the death of his father, Wangyal Lhakhang Jigme Dorji Wangchuck. -

The British Expedition to Sikkim of 1888: the Bhutanese Role

i i i i West Bohemian Historical Review VIII j 2018 j 2 The British Expedition to Sikkim of 1888: The Bhutanese Role Matteo Miele∗ In 1888, a British expedition in the southern Himalayas represented the first direct con- frontation between Tibet and a Western power. The expedition followed the encroach- ment and occupation, by Tibetan troops, of a portion of Sikkim territory, a country led by a Tibetan Buddhist monarchy that was however linked to Britain with the Treaty of Tumlong. This paper analyses the role of the Bhutanese during the 1888 Expedi- tion. Although the mediation put in place by Ugyen Wangchuck and his allies would not succeed because of the Tibetan refusal, the attempt remains important to under- stand the political and geopolitical space of Bhutan in the aftermath of the Battle of Changlimithang of 1885 and in the decades preceding the ascent to the throne of Ugyen Wangchuck. [Bhutan; Tibet; Sikkim; British Raj; United Kingdom; Ugyen Wangchuck; Thirteenth Dalai Lama] In1 1907, Ugyen Wangchuck2 was crowned king of Bhutan, first Druk Gyalpo.3 During the Younghusband Expedition of 1903–1904, the fu- ture sovereign had played the delicate role of mediator between ∗ Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, 46 Yoshida-shimoadachicho Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17F17306. The author is a JSPS International Research Fellow (Kokoro Research Center – Kyoto University). 2 O rgyan dbang phyug. In this paper it was preferred to adopt a phonetic transcrip- tion of Tibetan, Bhutanese and Sikkimese names.