Ray Charles Biographers…Excellent.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 08/19/2010 11:24 Am

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 08/19/2010 11:24 am WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 08/12/2010 to 08/18/2010 Last Period (TP) = 08/05/2010 to 08/11/2010 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 1 Kenny Burrell Be Yourself HighNote 2010 15 15 0 1 39 Tomas Janzon Experiences Changes 2010 15 2 13 3 2 Curtis Fuller I Will Tell Her Capri 2010 13 11 2 3 23 Chris Massey Vibrainium Self-Released 2010 13 3 10 5 3 Lois Deloatch Roots: Jazz, Blues, Spirituals Self-Released 2010 10 10 0 5 9 Buselli Wallarab Jazz Mezzanine Owl Studios 2010 10 5 5 Orchestra 7 16 Mark Weinstein Timbasa Jazzheads 2010 8 4 4 7 71 Amina Figarova Sketches Munich 2010 8 1 7 7 71 Steve Davis Images Posi-Tone 2010 8 1 7 10 5 Nnenna Freelon Homefree Concord 2010 7 8 -1 10 9 Fred Hersch Whirl Palmetto 2010 7 5 2 12 5 Tim Warfield A Sentimental Journey Criss Cross 2010 6 8 -2 12 8 Rita Edmond A Glance At Destiny T.O.T.I. 2010 6 6 0 12 16 Eric Reed & Cyrus Chestnut Plenty Swing, Plenty Soul Savant 2010 6 4 2 12 23 The Craig Russo Latin Jazz Mambo Influenciado Cagoots 2010 6 3 3 Project 12 39 Radam Schwartz Songs For The Soul Arabesque 2010 6 2 4 12 71 Tamir Hendelman Destinations Resonance 2010 6 1 5 12 267 Buckwheat Zydeco Lay Your Burden Down Alligator 2009 6 0 6 12 267 Charlie Musselwhite The Well Alligator 2010 6 0 6 20 4 Jason Moran Ten Blue Note 2010 5 9 -4 20 7 Stephen Anderson Nation Degeneration Summit 2010 5 7 -2 20 16 Keith Jarrett -

Arizona Musicfest 2021-22 Concert Season Announcement

azmusicfest.org NEWS RELEASE / CALENDAR LISTINGS ARIZONA MUSICFEST ANNOUNCES ITS 2021-22 CONCERT SEASON. CELEBRATING THE RETURN OF LIVE INDOOR PERFORMANCES, MUSICFEST PRODUCES AN EXCITING LINE-UP OF CONCERTS NOVEMBER THROUGH APRIL. LEGENDARY SINGER/SONGWRITER PAUL ANKA; BROADWAY ICON BERNADETTE PETERS; SUPERSTAR INSTRUMENTALIST KENNY G; COUNTRY MUSIC FAVORITE LEANN RIMES; BRAZILIAN LEGEND SERGIO MENDES; CLASSICAL VIRTUOSOS SARAH CHANG AND EMANUEL AX; PINK MARTINI AND THE TEXAS TENORS HEADLINE THE SPECIAL SEASON. June 2021 Media Contact: Allan Naplan, Executive and Producing Director For PR inquiries: [email protected] / (480) 488.0806 Photo Requests: PR Assets can also be obtained at the following link: https://azmusicfest.org/pr-assets/ To obtain further press materials, please email requests to [email protected]. ARIZONA MUSICFEST 2021-22 CONCERT SEASON Tickets are now on sale for Arizona Musicfest’s 31st anniversary season—The Stars Return to Musicfest! With great excitement and anticipation, Arizona Musicfest announces a starry lineup of exceptional artists to celebrate the return of live indoor concerts in North Scottsdale. Following the challenges and disappointments of last season, Musicfest is thrilled to regroup and renew its commitment to bringing the joy of music to all. In its largest season ever, Musicfest will produce 30 concerts between November and April. “As our community emerges from the difficulties of the last year, we are honored to engage and entertain audiences with exceptional performances that will uplift and reunite friends, neighbors, and artists around our shared love of music.” Allan Naplan, Arizona Musicfest’s executive and producing director, said. This special season’s lineup includes many great artists, some making their Musicfest debuts, while others returning due to popular demand. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Title Format Released Abyssinians, the Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin

Title Format Released Abyssinians, The Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin, Barbara The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 2) CD 2002 The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 1) CD 2002 Adams Johnny Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me CD 1991 Adams, Johnny I Won't Cry CD 1991 Walking On A Tightrope - The Songs Of Percy Mayfield CD 1989 Good Morning Heartache CD 1993 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Ade, King Sunny Odu CD 1998 Alabama Feels So Right CD 1981 Alexander, Arthur Lonely Just Like Me CD 1993 Allison, DeAnn Tumbleweed CD 2000 Allman Brothers Band, The Beginnings CD 1971 American Song-poem Anthology, The Do You Know The Difference Between Big Wood And Brush CD 2003 Animals, The Animals - Greatest Hits CD 1983 The E.P. Collection CD 1964 Aorta Aorta CD 1968 Astronauts, The Down The Line/ Travelin' Man CD 1997 Competition Coupe/Astronauts Orbit Kampus CD 1997 Rarities CD 1991 Go Go Go /For You From Us CD 1997 Surfin' With The Astronauts/Everything Is A-OK! CD 1997 Austin Lounge Lizards Paint Me on Velvet CD 1993 Average White Band Face To Face - Live CD 1997 Page 1 of 45 Title Format Released Badalamenti, Angelo Blue Velvet CD 1986 Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me CD 1992 Badfinger Day After Day [Live] CD 1990 The Very Best Of Badfinger CD 2000 Baker, Lavern Sings Bessie Smith CD 1988 Ball, Angela Strehli & Lou Ann Barton, Marcia Dreams Come True CD 1990 Ballard, Hank Sexy Ways: The Best of Hank Ballard & The Midnighters CD 1993 Band, The The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down: The Best Of The Band [Live] CD 1992 Rock Of Ages [Disc 1] CD 1990 Music From Big Pink CD 1968 The Band CD 1969 The Last Waltz [Disc 2] CD 1978 The Last Waltz [Disc 1] CD 1978 Rock Of Ages [Disc 2] CD 1990 Barker, Danny Save The Bones CD 1988 Barton, Lou Ann Read My Lips CD 1989 Baugh, Phil 64/65 Live Wire! CD 1965 Beach Boys, The Today! / Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) CD 1990 Concert/Live In London [Bonus Track] [Live] CD 1990 Pet Sounds [Bonus Tracks] CD 1990 Merry Christmas From The Beach Boys CD 2000 Beatles, The Past Masters, Vol. -

James Baldwin and Ray Charles in “The Hallelujah Chorus”

ESSAY “But Amen is the Price:” James Baldwin and Ray Charles in “The Hallelujah Chorus” Ed Pavlić University of Georgia Abstract Based on a recent, archival discovery of the script, “But Amen is the Price” is the first substantive writing about James Baldwin’s collaboration with Ray Charles, Cicely Tyson, and others in a performance of musical and dramatic pieces. Titled by Baldwin, “The Hallelujah Chorus” was performed in two shows at Carnegie Hall in New York City on 1 July 1973. The essay explores how the script and presentation of the material, at least in Baldwin’s mind, rep- resented a call for people to more fully involve themselves in their own and in each other’s lives. In lyrical interludes and dramatic excerpts from his classic work, “Sonny’s Blues,” Baldwin addressed divisions between neighbors, brothers, and strangers, as well as people’s dissociations from themselves in contemporary American life. In solo and ensemble songs, both instrumental and vocal, Ray Charles’s music evinced an alternative to the tradition of Americans’ evasion of each other. Charles’s sound meant to signify the his- tory and possibility of people’s attainment of presence in intimate, social, and political venues of experience. After situating the performance in Bald- win’s personal life and public worldview at the time and detailing the structure and content of the performance itself, “But Amen is the Price” discusses the largely negative critical response as a symptom faced by much of Baldwin’s other work during the era, responses that attempted to guard “aesthetics” generally— be they literary, dramatic, or musical—as class-blind, race-neutral, and apolitical. -

At the PEG EGAN Night Performing Arts Center Sunsetguitar Image Is Entitled “Broken Chords”, and Was Provided by the Artist, Cynthia Board

2016Sunday at the PEG EGAN Night Performing Arts Center SUNSETGuitar image is entitled “Broken Chords”, and was provided by the artist, Cynthia Board. Egg Harbor Amphitheater on Church Street. Concert Series FREE admission! Shows start at 7:00 pm. June 19 July 31 Tommy Castro Jackie Allen and the Quartet Painkillers July 10 and Corky Siegel the “Jackie Allen possesses a voice that combines the expressiveness of Annie Lennox and the pitch of Chamber Blues Rickie Lee Jones, while achieving its own bright, with special guests dramatic sound –sassy & tender.” – People Magazine Sue Demel and August 7 Matthew Santos “Gritty Chicago blues and rarefied classical Dailey & Vincent “Funky Southern Soul, big city blues and classic chamber music might not seem like a match made rock ...... Silvery guitar licks that simultaneously in heaven – until you’ve heard Corky Siegel bring sound familiar and fresh.” - San Francisco Chronicle the two together…a crowning achievement.” – Chicago Tribune June 26 July 17 Birds of Chicago and A collective based Art Stevenson around JT Nero the Grammy Award nomination for Best Country and Allison Russell. Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals, and won Whether touring High Water Band the 2011 Dove Award for Best Bluegrass Album with as duo or with the “Singing From The Heart”. full family band, Nero and Russell have emerged as August 14 two of the most and compelling new Larry Gatlin voices in North American Roots music. the Blackwood Brothers July 3 High Water’s repertoire is taken from many The Persuasions sources: the bluegrass classics of Bill Monroe and The Persuasions have been the acknowledged the Stanley Brothers, early country music and “Kings of A Capella” mountain songs. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

News Release / Calendar Listing

Website: www.azmusicfest.org • Box Office: (480) 422-8449 NEWS RELEASE / CALENDAR LISTING ARIZONA MUSICFEST ANNOUNCES ITS 2020-21 CONCERT SEASON. CELEBRATING ITS 30TH ANNIVERSARY, MUSICFEST PRODUCES AN EXCITING LINE-UP OF CONCERTS. PINK MARTINI, CLASSICAL MUSIC ICON EMANUEL AX, THE TEXAS TENORS, AND BROADWAY’S JOHN LLOYD YOUNG HEADLINE THE SPECIAL SEASON. July 2020 Media Contact: Allan Naplan, Executive and Producing Director For PR inquiries: [email protected] / (480) 488.0806 Press Note: A calendar directory follows the release’s narrative overview 2020-21 CONCERT SEASON NOTE: Arizona Musicfest annually produces concerts between November and March. Due to COVID- 19, Arizona Musicfest will not perform concerts in the fall of 2020, nor during the 2020 holiday season. Musicfest will instead produce a reduced season between January and April 2021. _____________________________________________________________________________________ RAY ON MY MIND January 12, 2021 • 8pm Highlands Church (9050 E. Pinnacle Peak Road, Scottsdale) -A special theatrical concert honoring the American music legend. The music and life story of the great Ray Charles comes alive in this special theatrical concert. Portraying Ray, master pianist/vocalist Kenny Brawner leads his 11-piece orchestra and three sultry vocalists (a la the Raelettes) in a musical journey through the American legend’s most popular hits. From What’d I Say? and I Got a Woman, to Mess Around and the classic Georgia On My Mind, the iconic music is interwoven with monologues depicting how gospel, blues, country and jazz influenced Ray’s singular style. STEVE TYRELL January 22, 2021 • 8pm Highlands Church (9050 E. Pinnacle Peak Road, Scottsdale) - One of the leading contemporary purveyors of classic American standards. -

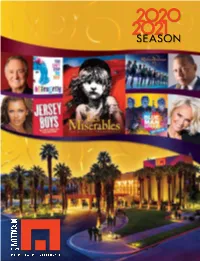

View Brochure

THE TIMES, THEY ARE A-CHANGING… C ONLY AT THE M CALLUM We’ve listened and recognize that many McCallum theatergoers prefer For more than three decades, the McCallum Theatre has brought the an earlier showtime. Beginning with the 2020-21 season: world to the Coachella Valley. Legendary entertainers. The biggest • Evening performances on Sunday – Thursday will begin at 7pm and best variety of shows. Performers at the top of their craft. • Friday and Saturday evening performances will remain at 8pm The 2020-2021 season is no exception. The McCallum is presenting one of its best Broadway seasons in recent years. Plus, there’s an • Matinees with no evening performances will begin at 3pm exciting array of McCallum premieres, brand new to the desert. • Broadway matinees will begin at 2pm. Broadway evening performance And audiences can expect lots of raucous comedy, international times may vary. song and dance, tributes to the jukebox of our lives and so much Note: all showtimes are subject to change depending on the needs of the more. There’s plenty to love – only at the McCallum. Get your performers or traveling companies. Please make sure to check your tickets to tickets today before the hottest shows sell out! ensure proper arrival time for all performances. It’s easy to purchase tickets online at www.mccallumtheatre.com. Or you can come to our box office at the McCallum (corner of Fred Waring and Monterey in Palm Desert). You can also McCallum audiences have truly embraced our Mitch’s order by phone at (760) 340-2787. Picks, returning for its seventh season in 2020-2021. -

Music Business

SINGLE COPY PRICE: 250 MUSIC BUSINESS Incorporating music reporter Vol.VIII,No. 40; May 9,1964 MILLION-$ TALENT BOOM New York Clubs Booking Best 40 1111 Names of All for Fair Visitors '.'NPIC(0111,MIjli By BEN GREVATT A MILLION DOLLARS worth of talent. That's the current story on the New York night club circuit as operators gear up to grab their share of the World's Fair sheckles being ploughed into the local economy by an estimated 35,000,000 visitors. The 1,000,000th visitor passed the turnstiles last week. Six of the major clubs right now are focusing on top head- LPII. Ets,.0,002 liners with five of these on the CHARTS & PICKS ZirSOVe.L distaff side. The lone male of eF Pop 100 . Page 21 Mid the group is Sammy Davis Jr., Pop LP's 24 whoopenedathree-week C & W 13 5rBSM stand at the Copa last week. Single Picks 18 of ',Wu BEYOND THIS, it's a battle Album Picks 22 of the blonds between Peggy Lee,holdingforthatthe - - . Americana's Royal Box andpartment, with Miss Lee tak- Patti Page, who moved intoing down $17,500 a week. In theWaldorf's Empire Roomaddition, she's got a suite of . He was just a delivery boy, but he caught his thumb ina last week. It's known that theher own and her entourage door during a recording session, and the screams that were taped Americana in particular is go-occupiesnineotherrooms made him a star . ." ing all out in the budget de - (nine!)in the high-rise hos- telry. -

Acoustic Sounds Winter Catalog Update

VOL. 8.8 VOL. 2014 WINTER ACOUSTICSOUNDS.COM ACOUSTIC SOUNDS, INC. VOLUME 8.8 The world’s largest selection of audiophile recordings Published 11/14 THE BEATLES IN MONO BOX SET AAPL 379916 • $336.98 The Beatles get back to mono in a limited edition 14 LP box set! 180-gram LPs pressed in Germany by Optimal Media. Newly remastered for vinyl from the analogue tapes by Sean Magee and Steve Berkowitz. The release includes all nine original mono mixed U.K. albums plus the original American- Cut to lacquer on a VMS80 lathe compiled mono Magical Mystery Tour and the Mono Masters, a three LP collection of Exclusive 12” 108-page hardbound book non-album tracks also compiled and mastered from the original analogue tapes. with rare studio photos! All individual albums available. See acousticsounds.com for details. FOUR MORE FROM THE FAB FOUR New LP Reissues - Including QRP Pressings! The below four Beatles LPs will be pressed in two separate runs. First up are 10,000 European-pressed copies. After those are sold through, the label will then release the Quality Record Pressings-pressed copies. All four albums are 180-gram double LPs! The Beatles 1967-1970 The Beatles 1962-1966 1 Love ACAP 48448 $35.98 ACAP 48455 $35.98 ACAP 60079 $35.98 ACAP 48509 $48.98 (QPR-pressed version; (QPR-pressed version; (QPR-pressed version; (QPR-pressed version; coming sometime in 2015) coming sometime in 2015) coming sometime in 2015) coming sometime in 2015) ACAP 484480 $35.98 ACAP 484550 $35.98 ACAP 600790 $35.98 ACAP ACAP 485090 $48.98 (European-pressed version; (European-pressed -

Kenneth Goldsmith

6799 Kenneth Goldsmith zingmagazine 2000 for Clark Coolidge 45 John Cage 42 Frank Zappa / Mothers 30 Charles Ives 28 Miles Davis 26 James Brown 25 Erik Satie 24 Igor Stravinsky 23 Olivier Messiaen 23 Neil Young 23 Kurt Weill 21 Darius Milhaud 21 Bob Dylan 20 Rolling Stones 19 John Coltrane 18 Terry Riley 18 Morton Feldman 16 Rod McKuen 15 Thelonious Monk 15 Ray Charles 15 Mauricio Kagel 13 Duke Ellington 3 A Kombi Music to Drive By, A Tribe Called Quest M i d n i g h t Madness, A Tribe Called Quest People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, A Tribe Called Quest The Low End Theory, Abba G reatest Hits, Peter Abelard Monastic Song, Absinthe Radio Trio Absinthe Radio Tr i o, AC DC Back in Black, AC DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, AC DC Flick of the Switch, AC DC For Those About to Rock, AC DC Highway to Hell, AC DC Let There Be R o c k, Johnny Ace Again... Johnny Sings, Daniel Adams C a g e d Heat 3000, John Adams Harmonium, John Adams Shaker Loops / Phrygian Gates, John Luther Adams Luther Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing, King Ade Sunny Juju Music, Admiral Bailey Ram Up You Party, Adventures in Negro History, Aerosmith Toys in the Attic, After Dinner E d i t i o n s, Spiro T. Agnew S p e a k s O u t, Spiro T. Agnew The Great Comedy Album, Faiza Ahmed B e s a r a h a, Mahmoud Ahmed E re Mela Mela, Akita Azuma Haswell & Sakaibara Ich Schnitt Mich In Den Finger, Masami Akita & Zbigniew Karkowski Sound Pressure Level, Isaac Albéniz I b e r i a, Isaac Albéniz Piano Music Volume II, Willy Alberti Marina, Dennis Alcapone Forever Version, Alive Alive!, Lee Allen Walkin’ with Mr.