Petrogenesis of the Platinum-Group Minerals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Profile

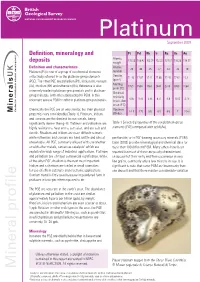

Platinum September 2009 Definition, mineralogy and Pt Pd Rh Ir Ru Os Au nt Atomic 195.08 106.42 102.91 192.22 101.07 190.23 196.97 deposits weight opme vel Atomic Definition and characteristics 78 46 45 77 44 76 79 de number l Platinum (Pt) is one of a group of six chemical elements ra UK collectively referred to as the platinum-group elements Density ne 21.45 12.02 12.41 22.65 12.45 22.61 19.3 (gcm-3) mi (PGE). The other PGE are palladium (Pd), iridium (Ir), osmium e Melting bl (Os), rhodium (Rh) and ruthenium (Ru). Reference is also 1769 1554 1960 2443 2310 3050 1064 na point (ºC) ai commonly made to platinum-group metals and to platinum- Electrical st group minerals, both often abbreviated to PGM. In this su resistivity r document we use PGM to refer to platinum-group minerals. 9.85 9.93 4.33 4.71 6.8 8.12 2.15 f o (micro-ohm re cm at 0º C) nt Chemically the PGE are all very similar, but their physical Hardness Ce Minerals 4-4.5 4.75 5.5 6.5 6.5 7 2.5-3 properties vary considerably (Table 1). Platinum, iridium (Mohs) and osmium are the densest known metals, being significantly denser than gold. Platinum and palladium are Table 1 Selected properties of the six platinum-group highly resistant to heat and to corrosion, and are soft and elements (PGE) compared with gold (Au). ductile. Rhodium and iridium are more difficult to work, while ruthenium and osmium are hard, brittle and almost pentlandite, or in PGE-bearing accessory minerals (PGM). -

Predictability of Pothole Characteristics and Their Spatial Distribution At

79_Chitiyo:Template Journal 12/15/08 11:16 AM Page 733 Predictability of pothole characteristics J o and their spatial distribution at u Rustenburg Platinum Mine r n by G. Chitiyo*, J. Schweitzer*, S. de Waal*, P. Lambert*, and a P. Olgilvie* l P a p Synopsis thermo-chemical erosion of the cumulus floor by new influxes of superheated magma best explains the observed data. e Prediction of pothole characteristics is a challenging task, Partial to complete melting of the cumulate floor occurred in r confronting production geologists at the platinum mines of three phases. The first represents the emplacement of hot the Bushveld Complex. The frequency, distribution, size, magma. This magma, due to turbulent flow and high chemical shape, severity and relationship (FDS3R) of potholes has a and physical potential, aggressively attacks the existing floor huge impact on mine planning and scheduling, and (crystal mush on the magma/floor interface). Regional consequently cost. It is with this in mind that this study was erosion is manifested by large, often coalescing potholes. initiated. During the second phase, when the magma emplacement Quantitative analysis of potholes indicates that pothole process ceased and cooling in situ started, two distinct size (area covered) can be described by two partly periods of pothole formation ensued. The first is related to overlapping lognormal distributions. These are referred to as rapid cooling along the relatively steep part of the Newton Populations A (smaller) and B (larger). The range of Cooling Curve, when Population B potholes nucleated observed pothole sizes conforms to a simple double randomly and grew rapidly with concurrent convective exponential growth model based on Newton’s Cooling Curve. -

Washington State Minerals Checklist

Division of Geology and Earth Resources MS 47007; Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Washington State 360-902-1450; 360-902-1785 fax E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dnr.wa.gov/geology Minerals Checklist Note: Mineral names in parentheses are the preferred species names. Compiled by Raymond Lasmanis o Acanthite o Arsenopalladinite o Bustamite o Clinohumite o Enstatite o Harmotome o Actinolite o Arsenopyrite o Bytownite o Clinoptilolite o Epidesmine (Stilbite) o Hastingsite o Adularia o Arsenosulvanite (Plagioclase) o Clinozoisite o Epidote o Hausmannite (Orthoclase) o Arsenpolybasite o Cairngorm (Quartz) o Cobaltite o Epistilbite o Hedenbergite o Aegirine o Astrophyllite o Calamine o Cochromite o Epsomite o Hedleyite o Aenigmatite o Atacamite (Hemimorphite) o Coffinite o Erionite o Hematite o Aeschynite o Atokite o Calaverite o Columbite o Erythrite o Hemimorphite o Agardite-Y o Augite o Calciohilairite (Ferrocolumbite) o Euchroite o Hercynite o Agate (Quartz) o Aurostibite o Calcite, see also o Conichalcite o Euxenite o Hessite o Aguilarite o Austinite Manganocalcite o Connellite o Euxenite-Y o Heulandite o Aktashite o Onyx o Copiapite o o Autunite o Fairchildite Hexahydrite o Alabandite o Caledonite o Copper o o Awaruite o Famatinite Hibschite o Albite o Cancrinite o Copper-zinc o o Axinite group o Fayalite Hillebrandite o Algodonite o Carnelian (Quartz) o Coquandite o o Azurite o Feldspar group Hisingerite o Allanite o Cassiterite o Cordierite o o Barite o Ferberite Hongshiite o Allanite-Ce o Catapleiite o Corrensite o o Bastnäsite -

New Mineral Names*,†

American Mineralogist, Volume 104, pages 625–629, 2019 New Mineral Names*,† DMITRIY I. BELAKOVSKIY1 AND FERNANDO CÁMARA2 1Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninskiy Prospekt 18 korp. 2, Moscow 119071, Russia 2Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra “Ardito Desio”, Universitá di degli Studi di Milano, Via Mangiagalli, 34, 20133 Milano, Italy IN THIS ISSUE This New Mineral Names has entries for 8 new minerals, including fengchengite, ferriperbøeite-(Ce), genplesite, heyerdahlite, millsite, saranchinaite, siudaite, vymazalováite and new data on lavinskyite-1M. FENGCHENGITE* X-ray diffraction pattern [d Å (I%; hkl)] are: 7.186 (55; 110), 5.761 (44; 113), 4.187 (53; 123), 3.201 (47; 028), 2.978 (61; 135). 2.857 (100; 044), G. Shen, J. Xu, P. Yao, and G. Li (2017) Fengchengite: A new species with 2.146 (30; 336), 1.771 (36; 24.11). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data the Na-poor but vacancy-dominante N(5) site in the eudialyte group. shows the mineral is trigonal, space group R3m, a = 14.2467 (6), c = Acta Mineralogica Sinica, 37 (1/2), 140–151. 30.033(2) Å, V = 5279.08 Å3, Z = 3. The structure was solved by direct methods and refined to R = 0.043 for all unique I > 2σ(I) reflections. Fengchengite (IMA 2007-018a), Na Ca (Fe3+,) Zr Si (Si O ) 12 3 6 3 3 25 73 Fenchengite is the Fe3+ analog of eudialyte with a structural difference (H O) (OH) , trigonal, is a new eudialyte-group mineral discovered in 2 3 2 in vacancy dominant N5 site and splitting its Na site N1 into N1a and the agpaitic nepheline syenites and its pegmatite facies near the Saima N1b sites. -

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE HUGH ALLSOPP LABORATORY University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE HUGH ALLSOPP LABORATORY University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX- PROCESS OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT J.A. KINNAIRD, F.J. KRUGER, P.A.M. NEX and R.G. CAWTHORN INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 369 UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND JOHANNESBURG CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX – PROCESSES OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT by J. A. KINNAIRD, F. J. KRUGER, P.A. M. NEX AND R.G. CAWTHORN (Department of Geology, School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, P.O. WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa) ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 369 December, 2002 CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX – PROCESSES OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT ABSTRACT The mafic layered suite of the 2.05 Ga old Bushveld Complex hosts a number of substantial PGE-bearing chromitite layers, including the UG2, within the Critical Zone, together with thin chromitite stringers of the platinum-bearing Merensky Reef. Until 1982, only the Merensky Reef was mined for platinum although it has long been known that chromitites also host platinum group minerals. Three groups of chromitites occur: a Lower Group of up to seven major layers hosted in feldspathic pyroxenite; a Middle Group with four layers hosted by feldspathic pyroxenite or norite; and an Upper Group usually of two chromitite packages, hosted in pyroxenite, norite or anorthosite. There is a systematic chemical variation from bottom to top chromitite layers, in terms of Cr : Fe ratios and the abundance and proportion of PGE’s. Although all the chromitites are enriched in PGE’s relative to the host rocks, the Upper Group 2 layer (UG2) shows the highest concentration. -

Mineral Processing

Mineral Processing Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy 1st English edition JAN DRZYMALA, C. Eng., Ph.D., D.Sc. Member of the Polish Mineral Processing Society Wroclaw University of Technology 2007 Translation: J. Drzymala, A. Swatek Reviewer: A. Luszczkiewicz Published as supplied by the author ©Copyright by Jan Drzymala, Wroclaw 2007 Computer typesetting: Danuta Szyszka Cover design: Danuta Szyszka Cover photo: Sebastian Bożek Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej Wybrzeze Wyspianskiego 27 50-370 Wroclaw Any part of this publication can be used in any form by any means provided that the usage is acknowledged by the citation: Drzymala, J., Mineral Processing, Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy, Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr., 2007, www.ig.pwr.wroc.pl/minproc ISBN 978-83-7493-362-9 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part I Introduction to mineral processing .....................................................................13 1. From the Big Bang to mineral processing................................................................14 1.1. The formation of matter ...................................................................................14 1.2. Elementary particles.........................................................................................16 1.3. Molecules .........................................................................................................18 1.4. Solids................................................................................................................19 -

Temagamite Pd3hgte3 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Temagamite Pd3HgTe3 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Orthorhombic. Point Group: n.d. As rounded to irregular inclusions, to 115 µm, in chalcopyrite. Physical Properties: Hardness = n.d. VHN = 92 (25 g load). D(meas.) = 9.5 (synthetic). D(calc.) = 9.45 Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: In polished section, white with a gray tinge. Luster: Metallic. Anisotropism: Weak in air, stronger in oil, in pale gray to dark gray. R1–R2: (470) 51.8–52.8, (546) 52.9–53.9, (589) 54.2–55.0, (650) 57.1–57.7 Cell Data: Space Group: n.d. (synthetic). a = 11.608(2) b = 12.186(1) c = 6.793(1) Z=6 X-ray Powder Pattern: Synthetic. 2.912 (10), 2.187 (9), 1.959 (7), 1.661 (5), 1.624 (5), 1.462 (5), 1.155 (5) Chemistry: (1) (2) Pd 34.9 34.5 Pt 1.0 Hg 22.1 22.0 Bi n.d. 0.13 Te 42.1 42.1 Total 99.1 99.73 (1) Temagami Mine, Canada; by electron microprobe, corresponding to Pd2.99Hg1.00Te3.01. (2) Stillwater complex, Montana, USA; by electron microprobe, corresponding to (Pd2.95Pt0.05)Σ=3.00Hg1.00Te3.00. Occurrence: Cogenetic with moderately high-temperature invasive chalcopyrite magma (Temagami Mine, Canada). Association: Merenskyite, hessite, chalcopyrite, st¨utzite. Distribution: In Canada, in Ontario, from the Temagami Cu–Ni mine, Temagami Island, Lake Temagami, Nipissing district [TL] and from a prospect near Rathbun Lake. In the USA, from the Stillwater complex, Montana; and the New Rambler Cu–Ni mine, Medicine Bow Mountains, east of Encampment, Albany Co., Wyoming. -

Download the Scanned

American Mineralogist, Volume 59, pages 906-918, 1974 Domainsin Minerals Rosnnr E. NpwNnarvr Materials ResearchLaboratory, The PennsylaaniaState Uniuersity, Uniuersity Park, Pennsyluania16802 Abstract Mimetic twinning in minerals is reviewed in terms of the tensor properties of the orientation states, showing which forces are eftective in moving domain walls. Following the Aizu method, various types of ferroic species are developed frorn the free energy function. Examples of ferroelectric, ferromagnetic, ferroelastic, ferrobielectric, ferrobimagnetic, ferrobielastic, ferro- elastoelectric, ferromagnetoelastic, and ferromagnetoelectric minerals are described. Introduction and ferromagnetoelectric.As explained later, each Twinning is widely used in mineral identification type of domain reorientationarises from a particular and in elucidating the formation conditions of rocks. term in the free energy function. The distribution of transformation twins in rock- A ferroic crystal contains two or more possible forming minerals enables one to establish the orientationstates or domains;under a suitably chosen thermal processes that have occurred in the rock. driving force the domain walls move, switching the Mechanical twinning is studied by petrologists in crystal from one orientation stateto another. Switch- the analysis of flow effects. In rock magnetism, it ing may be accomplishedby mechanicalstress (a), is the arrangement of ferromagnetic domains which electricfield (E), magneticfield (I/), or somecombina- determines remanent magnetization. These are but tion of the three. Ferroelectric, ferroelastic, and a few examples of twin phenomena in minerals. ferromagneticmaterials are well known examplesof In the past twinned crystals have been classified primary ferroic crystals in which the orientation according to twin-laws and morphology, or accord- statesdiffer respectivelyin spontaneouspolarization ing to their mode of origin, or on a structural basis, P,",, spontaneousstrain 6r"r and spontaneous but there is another classification scheme which magnetizatiorrMr"t. -

Sampling and Estimation of Diamond Content in Kimberlite Based on Microdiamonds Johannes Ferreira

Sampling and estimation of diamond content in kimberlite based on microdiamonds Johannes Ferreira To cite this version: Johannes Ferreira. Sampling and estimation of diamond content in kimberlite based on micro- diamonds. Other. Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris, 2013. English. NNT : 2013ENMP0078. pastel-00982337 HAL Id: pastel-00982337 https://pastel.archives-ouvertes.fr/pastel-00982337 Submitted on 23 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N°: 2009 ENAM XXXX École doctorale n° 398: Géosciences et Ressources Naturelles Doctorat ParisTech T H È S E pour obtenir le grade de docteur délivré par l’École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris Spécialité “ Géostatistique ” présentée et soutenue publiquement par Johannes FERREIRA le 12 décembre 2013 Sampling and Estimation of Diamond Content in Kimberlite based on Microdiamonds Echantillonnage des gisements kimberlitiques à partir de microdiamants. Application à l’estimation des ressources récupérables Directeur de thèse : Christian LANTUÉJOUL Jury T M. Xavier EMERY, Professeur, Université du Chili, Santiago (Chili) Président Mme Christina DOHM, Professeur, Université du Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (Afrique du Sud) Rapporteur H M. Jean-Jacques ROYER, Ingénieur, HDR, E.N.S. Géologie de Nancy Rapporteur M. -

Copper in South Africa-Part 11

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall., vol. 85, no. 4. Apr. 1985. pp. 109-124 Copper in South Africa-Part 11 by C.O. BEALE* SYNOPSIS This, the second and final part of a review on the subject(the first part was published in the March issue of this Jouma/), deals in detail with the 9 copper-producing companies in the Republic of South Africa. These are The Phosphate Development Corporation, Prieska Copper Mines (Pty) Ltd, Black Mountain Mineral Development Co. (Pty) Ltd, Rustenburg Platinum Holdings Ltd, Impala Platinum Holdings Ltd, Western Platinum Ltd, The O'okiep Copper Co. Ltd, Messina Ltd, and Palabora Mining Co. Ltd. The following are described for each company: background, development, geology, mining, concentration, and current situation. The last-mentioned company, being South Africa's largest producer, is dealt with in greatest detail. SAMEVATTING . Hierdie tweede en slotdeel van 'n oorsig oor die onderwerp (die eerste deal het in die Maart-uitgawe van hierdie Tydskrif verskyn) handel in besonderhede oor die 9 koperproduserende maatskappye in the Republiek van Suid- Afrika. Hulle is die Fosfaat-ontginningskorporasie, Prieska Copper Mines (Pty) Ltd, Black Mountain Mineral Develop- ment Co. (Pty) Ltd, Rustenburg Platinum Holdings Ltd, Impala Platinum Holdings Ltd, Western Platinum Ltd, The O'okiep Copper Co. Ltd, Messina Ltd, en Palabora Mining Co. Ltd. Die volgende wQfd met betrekking tot elkeen van die maatskappye bespreek: agtergrond, ontwikkeling, geologie, mynbou, konsentrsie en huidige posisie. Die laasgenoemde maatskappy, wat Suid-Afrika se grootste produsent is, word in die meeste besonderhede bespreek. THE PHOSPHATE DEVELOPMENT CORP. CFOSKOR)' This Company was formed in 1951, on Government Foskor concentrate contributes significantly to the load initiative, to exploit the apatite (phosphate) resources of on Palabora's smelter and refinery, and also the annual the Phalaborwa Igneous Complex (Fig. -

Nickel Minerals from Barberton, South Africa: I

American Mineralogist, Volume 58, pages 733-735, 1973 NickelMinerals from Barberton,South Africa: Vl. Liebenbergite,A NickelOlivine SvsneNoA. nn Wnar Nationnl Institute lor Metallurgy, I Yale Road.,Milner Park, I ohannesburg,South Alrica Lnwrs C. ClI.x Il. S. GeologicalSuruey, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, California 94025 Abstract Liebenbergite, a nickel olivine from the mineral assemblage trevorite-liebenbergite-nickel serpentine-nickel ludwigite-bunsenite-violarite-millerite-gaspeite-nimite, is described mineral- ogically.Ithasa-1.820,P-1.854,7-1.888,ZVa-88",specificgravity-4'60,Mohs hardness- 6 to 6.5, a - 4.727, b - 10.191,c = 5.955A, and Z - 4. X-ray powder data (48 lines) were indexed according to the space grottp Pbnm. The mean chemical composi- tion, calculated from electron microprobe analyses of eight separate liebenbergite grains, gives the mineral formula: (NL eMgoaCoo,sFeo o)Sio "nOn The name is for W. R. Liebenberg, Deputy Director-General of the National Institute for Metallurgy, South Africa. Introduction mission on New Minerals and Mineral Names (rMA). A re-investigationof the trevorite deposit at Bon Accord in the Barberton Mountain Land, South Experimental Methods Africa, led to the discovery of two peculiar but distinct nickel mineral assemblages.Minerals from The refractive indices were determined by the the assemblagewillemseite-nimite-feroan trevorite- conventional liquid immersion method using a reevesite-millerite-violarite-goethitehave been de- sodium lamp as light source.The optical and crystal scribed in earlier papers in this series (de Waal, morphologicalparameters were studiedwith the aid 1969, l97oa, 1970b;de Waal and Viljoen, I97L). of a universal stage. -

GSA TODAY Conference, P

Vol. 10, No. 2 February 2000 INSIDE • GSA and Subaru, p. 10 • Terrane Accretion Penrose GSA TODAY Conference, p. 11 A Publication of the Geological Society of America • 1999 Presidential Address, p. 24 Continental Growth, Preservation, and Modification in Southern Africa R. W. Carlson, F. R. Boyd, S. B. Shirey, P. E. Janney, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 5241 Broad Branch Road, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20015, USA, [email protected] T. L. Grove, S. A. Bowring, M. D. Schmitz, J. C. Dann, Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA D. R. Bell, J. J. Gurney, S. H. Richardson, M. Tredoux, A. H. Menzies, Department of Geological Sciences, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7700, South Africa D. G. Pearson, Department of Geological Sciences, Durham University, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK R. J. Hart, Schonland Research Center, University of Witwater- srand, P.O. Box 3, Wits 2050, South Africa A. H. Wilson, Department of Geology, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa D. Moser, Geology and Geophysics Department, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0111, USA ABSTRACT To understand the origin, modification, and preserva- tion of continents on Earth, a multidisciplinary study is examining the crust and upper mantle of southern Africa. Xenoliths of the mantle brought to the surface by kimber- lites show that the mantle beneath the Archean Kaapvaal Figure 2. Bouguer gravity image (courtesy of South African Council for Geosciences) craton is mostly melt-depleted peridotite with melt extrac- across Vredefort impact structure, South Africa. Color scale is in relative units repre- senting total gravity variation of 90 mgal across area of figure.