Henry Fielding -15 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web 2.0 Storytellingemergence of a New Genre by Bryan Alexander and Alan Levine

Teaching and Learning Web 2.0 StorytellingEmergence of a New Genre By Bryan Alexander and Alan Levine story has a beginning, a middle, and a cleanly wrapped-up end- ing. Whether told around a campfire, read from a book, or played on a DVD, a story goes from point A to B and then C. It follows a trajectory, a Freytag Pyramid—perhaps the line of a human life or the stages of the hero’s journey. A story is told by one person or by a creative team to an audience that is usually quiet, even receptive. Or at least that’s what a story used to be, and that’s how a story used to be told. Today, with digital net- Aworks and social media, this pattern is changing. Stories now are open-ended, branching, hyperlinked, cross-media, participatory, exploratory, and unpre- dictable. And they are told in new ways: Web 2.0 storytelling picks up these new types of stories and runs with them, accelerating the pace of creation and participation while revealing new directions for narratives to flow. Bryan Alexander is Director of Research at the National Institute for Technology and Liberal Education (NITLE, http:// nitle.org). He blogs at <http://b2e.nitle.org/>. Alan Levine is Vice President, Community, and Chief Technology Officer for the New Media Consortium (NMC). He barks about technology at <http://cogdog blog.com>. 40 EDUCAUSE r e v i e w - November/December 2008 © 2008 Bryan Alexander and Alan Levine Illustration by David Lesh, © 2008 Definitions and Histories such as Dreamweaver, an arcane method connections in between. -

Blogs and the Narrativity of Experience

Blogs and the Narrativity of Experience José Ángel García Landa Universidad de Zaragoza [email protected] http://www.garcialanda.net Blogs and the Narrativity of Experience This paper undertakes an analysis of the narrativity of a form of discourse which has appeared recently (blogs) within the framework of an emergentist theory of narrativity and its discursive modes. The narrative/discursive characteristics of blogs emerge from a preexistent ground of more basic or less specific communicative practices; and narrative discursivity itself is an emergent phenomenon with respect to other cognitive and experiential phenomena. A number of formal and communicative characteristics of blog writing and of the blogosphere are discussed as emergent modes of experience within the pragmatic context of computer-mediated communication. _________________ 1 We shall undertake an analysis of the narrativity proper to a discursive form of recent appearance, weblogs or blogs, within the framework of an emergentist theory of narrativity and of its discursive modes. The narrative- discursive characteristics of blogs emerge from a prior basis of simpler or less specific communicative practices. And the narrativity of discourse is itself an emergent phenomenon with respect to other cognitive and experiential phenomena which necessarily underpin it, and are the basis on which its emergent nature must be defined. That is to say, there must be processes first, in order for processual representations to exist, and these representations must exist in simple forms before they give rise to complex narrative forms, associated to specific cultural and communicational contexts—for instance, the development of computer-mediated communicative interaction on the Web. Processes - Representations - Narratives - Narratologies Let us begin with absolute generality—with the narrativity of experience itself, situating narratives, and narratology, within an emergentist/evolutionary theory of reality. -

How to Write Best-Selling Fiction

kfajs aslkjf;laskjfa;lkesfhj kfajs aslkjf;laskjfa;lkesfhj kfajs aslkjf;laskjfa;lkesfhj Topic Subtopic kfajs aslkjf;laskjfa;lkesfhj. Literature & Language Writing How to Write Best-Selling Fiction Write to How “Pure intellectual stimulation that can be popped into the [audio or video player] anytime.” How to Write —Harvard Magazine “Passionate, erudite, living legend lecturers. Academia’s best lecturers are being captured on tape.” Best-Selling Fiction —The Los Angeles Times Course Guidebook “A serious force in American education.” —The Wall Street Journal James Scott Bell Novelist and Writing Instructor James Scott Bell is an award-winning novelist and writing instructor. He is a winner of the International Thriller Writers Award and the author of a best-selling book on writing, Plot & Structure: Techniques and Exercises for Crafting a Plot That Grips Readers from Start to Finish. He is also the author of numerous novels. Mr. Bell has taught novel writing at Pepperdine University as well as in writing seminars across the United States and many parts of the world, including Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom. THE GREAT COURSES® Corporate Headquarters 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, VA 20151-2299 USA Guidebook Phone: 1-800-832-2412 www.thegreatcourses.com Professor Photo: © Jeff Mauritzen - inPhotograph.com. Cover Image: © Need Image Credit.. Course No. 2533 © 2019 The Teaching Company. PB2533A Published by THE GREAT COURSES Corporate Headquarters 4840 Westfields Boulevard | Suite 500 | Chantilly, Virginia | 20151‑2299 [phone] 1.800.832.2412 | [fax] 703.378.3819 | [web] www.thegreatcourses.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2019 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. -

Web 2.0 Storytelling: Emergence of a New Genre (EDUCAUSE Revi

Web 2.0 Storytelling: Emergence of a New Genre (EDUCAUSE Revi... http://connect.educause.edu/Library/EDUCAUSE+Review/Web20Sto... © 2008 Bryan Alexander and Alan Levine. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative VIEW A PDF Commons Attribution 3.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). OF THIS ARTICLE EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 43, no. 6 (November/December 2008) Web 2.0 Storytelling: Emergence of a New Genre BRYAN ALEXANDER AND ALAN LEVINE Bryan Alexander is Director of Research at the National Institute for Technology and Liberal Education (NITLE, http://nitle.org). He blogs at http://b2e.nitle.org/ . Alan Levine is Vice President, Community, and Chief Technology Officer for the New Media Consortium (NMC, http://www.nmc.org). He barks about technology at http://cogdogblog.com Comments on this article can be sent to the authors at [email protected] and [email protected] and/or can be posted to the web via the link at the bottom of this page. A story has a beginning, a middle, and a cleanly wrapped-up ending. Whether told around a campfire, read from a book, or played on a DVD, a story goes from point A to B and then C. It follows a trajectory, a Freytag Pyramid—perhaps the line of a human life or the stages of the hero's journey. A story is told by one person or by a creative team to an audience that is usually quiet, even receptive. Or at least that’s what a story used to be, and that’s how a story used to be told. -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Leishman, Donna (2015) The challenge of visuality for electronic literature: Conference panel: The medium. In: The end(s) of electronic literature. ELMCIP / Irish Research Council & European Council, Bergen, pp. 138-139. ISBN 9788299908986, 9788299908979 Published by: ELMCIP / Irish Research Council & European Council URL: This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/42848/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) 2015: The End(s) of Electronic Literature 2015: The End(s) of Electronic Literature Electronic Literature Organization Conference Program and Festival Catalog Editors: Anne Karhio, Lucas Ramada Prieto, Scott Rettberg ELMCIP, University of Bergen Dept. -

Il Fenomeno Blog

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI CAGLIARI Facoltà di Studi Umanistici Corso di Laurea in Lettere Moderne IL FENOMENO BLOG Relatore Tesi di laurea di Prof. Carlo Figari Francesca Matta !1 Anno Accademico 2013-2014 Indice Introduzione 3 1. Genesi e diffusione del blog: dalla NewsPage alla Weblog Community 9 1.1 Tipologie e caratteri del blog 15 1.2 La diffusione del blog in Italia 19 2. Blog e giornalismo: il blogging è giornalismo? 24 2.1 Mediasfera e Blogosfera: due sistemi a confronto 30 2.2 Interrelazione tra Blogosfera e Mediasfera 36 2.3 Watchblogging 41 3. I blog dei quotidiani italiani: i numeri, i contenuti, i giornalisti 46 3.1 Dai blog giornalistici ai blog in redazione 56 3.2 I blog dei quotidiani italiani: Il Corriere della Sera e La Repubblica, L'Unione Sarda e La Nuova Sardegna 60 4. Intervista a Beppe Severgnini 69 Conclusioni 75 Glossario 79 Bibliografia 88 Sitografia 90 !2 Introduzione Il fenomeno blog, sviluppatosi all'inizio degli anni duemila, ha visto un progressivo cambiamento della propria forma e funzione, che ha coinvolto sia i media tradizionali sia i nuovi social media, diventando un importante collegamento tra i due sistemi d'informazione. Oggi sono presenti più di 152 milioni di blog1, di cui quasi la metà proviene dagli Stati Uniti2, seguiti dall'Europa, l'Oceania, l'America latina, il nord America, il sud Asia, l'Asia dell'est, il Medioriente e l'Africa. La maggior parte dei blogger raggiungono un'età media compresa tra i 25 e i 40 anni, mentre solo un terzo supera i 44 anni; il 37% dei lavoratori a tempo pieno indica il blog come principale fonte di guadagno3, perciò tende ad aggiornarlo più frequentemente rispetto ad altre categorie, come gli hobbisti, i lavoratori part-time e i lavoratori dipendenti: il 26% dei rispondenti sostiene di arrivare a pubblicare tre post al giorno. -

Blog Fiction: the Relational Poetics of a Distributed Narrative Form

Blog Fiction: The Relational Poetics of a Distributed Narrative Form by Emma Segar A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Edge Hill University. Submitted October 2015 1 Abstract This analysis explores blog fiction as a distributed narrative form, and the relational nature of the reading and writing processes that shape its poetics. It does this primarily through the analysis of Bad Influences1, the blog fiction that forms the creative part of this thesis. Bad Influences tells a disaster story distributed over four separate fictional blogs, exploring online identities, friendships, and how our relations to the world and our communities are shaped by the stories we tell about ourselves. Jill Walker Rettberg’s ideas on distributed narrative2 are used to investigate blog fiction’s distributions in time, space and authorship, and how these affect its narrative time, linearity, interactivity and poetics. The processes of writing and posting Bad Influences, and engaging with its readers, show how the use of the blog as a medium determines the characteristics of blog fiction as a form, and how the relations that emerge between readers, writers and the text produce, in Aukje van Rooden’s term, a relational poetics.3 This analysis concludes with an application of relational poetics to blog fiction and digital interactive fiction in general, touching upon emerging forms of fiction on social media platforms (e.g. Twitter fiction and interactive multiplayer narrative apps), in which relational processes are an essential component of the text, rather than simply a means to its access. -

The Early Novel, the Serial, and the Narrative Archive." in Blogtalks Reloaded: Social Software-Research & Cases, Ed

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Faculty Publications and Research Pomona Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2007 The leP asure of the Blog: The aE rly Novel, the Serial, and the Narrative Archive Kathleen Fitzpatrick Pomona College Recommended Citation Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. "The leP asure of the Blog: The Early Novel, the Serial, and the Narrative Archive." In Blogtalks Reloaded: Social Software-Research & Cases, ed. Thomas N Burg and Jan Schmidt. [Vienna 2006 www.blogtalk.net]. Vienna: Social Software Lab, 2007. Print. This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLEASURE OF THE BLOG: THE EARLY NOVEL, THE SERIAL, AND THE NARRATIVE ARCHIVE Kathleen Fitzpatrick Pomona College, Claremont, CA, USA [email protected] http://www.plannedobsolescence.net „Pleasure results from the production of meanings of the world and of self that are felt to serve the interests of the reader rather than those of the dominant.” — John Fiske (1987: 19) As this paper, which is a preliminary gesture toward a much larger work-in-progress, centers around the relationship between writing and the self as constructed through blogging, it seems almost necessary for me to begin with the personal, with my own self. This self is of course a multiply constructed subjectivity: there is the me that teaches, the me that attends endless meetings, the me that you might meet at a conference, the me that you could run into on the street. -

Will Spook You for Real

Will Spook You For Real. Strategies of Inspiring Societal Anxieties in Popular Forms of Fiction Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Neuphilologischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Christina Maria Huber M.A. 2016 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Peter Paul Schnierer Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Günter Leypoldt Dedicated with boundless love and gratitude to Gertraud Teiche, who taught me that kein Weg ist umsonst. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. Peter Paul Schnierer, for giving me the chance to work on this project, as well as for his time, his patience, and his helpful input. I am also indebted to my wonderful friends who have spent so much of their valuable time reading my dissertation and providing me with helpful comments and suggestions – above all, Edward Miles, Tina Jäger, Wiebke Stracke, and Matylda Stoy. Elke Hiltner was my ‘emotions supervisor’ in the English Department – a demanding job, but she performed wonderfully. Thanks to all the kind people around me who supported and guided me, and gave me encouragement, feedback and/or coffee. Finally, I owe more to Falko Sievers than I could possibly put in words. Thank you for everything you do and everything you are. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE 1. Introduction: “Will spook you for real” ...................................................... 2 2. Definitions and demarcations .................................................................. 7 2.1 Societal Anxieties .............................................................................. -

Curriculum Vitae

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Teaching „Writing 2.0‟ – The Impact of Web 2.0 Technologies on Teaching Writing in the EFL Classroom” Verfasserin Julia Prinz angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil) Wien, 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 362 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramt UF Englisch UF Russisch Betreuer: Dr. Norbert Pachler Acknowledgements/Danksagung Zuallererst möchte ich meinen Eltern, Gertrude und Manfred Prinz, für die Ermöglichung meines Studiums und ihre jahrelange finanzielle und seelische Unterstützung dabei danken. Durch ihr Verständnis, ihre Hilfe und Aufopferung habe ich mich immer in der nötigen Weise auf mein Studium konzentrieren können. Ohne den starken Zusammenhalt meiner Familie wäre ich sicher nicht so schnell an diesem Punkt angelangt und hätte mich beruflich und privat nicht zu dem Menschen entwickeln können, der ich heute bin. Mein Dank gilt außerdem meinem Freund, Marcel Hauer, der mir während meines gesamten Studiums immer mit Rat und Tat zur Seite stand, mir jeden Tag von neuem Mut und Selbstvertrauen gab, mir bei meinen Problemen zuhörte und mich in all meinen Entscheidungen unterstützte. Ich danke ihm auch dafür, dass er mich immer wieder erfolgreich aus dem stressbehafteten Alltag herausholte und mich in gleicher Weise durch Gespräche und Diskussionen in meiner Arbeit beflügelte. Weiters möchte ich mich für die großartige Betreuung von Dr. Norbert Pachler bedanken, der trotz der geographischen Distanz immer schnell auf meine Anliegen reagierte und mich sowohl in seinem Kurs als auch bei den Anmerkungen zu meiner Arbeit durch sein Wissen und seine Erfahrung unverzichtbar bereicherte. Im selben Atemzug muss ich daher auch dem Zufall danken, der mich im Sommersemester 2009 in Dr. -

Teaching Literature for the 21St Century

Silvia Pokrivčáková Eva Vitézová Gabriela Magalová Jana Javorčíková Teaching Literature for the 21st Century Vyučovanie literatúry pre 21. storočie Trnavská univerzita v Trnave Pedagogická fakulta 2017 Teaching literature for the 21st century Vyučovanie literatúry pre 21. storočie 2 Teaching literature for the 21st century Vyučovanie literatúry pre 21. storočie Silvia Pokrivčáková Eva Vitézová Gabriela Magalová Jana Javorčíková Teaching Literature for the 21st Century Vyučovanie literatúry pre 21. storočie 2017 3 Teaching literature for the 21st century Vyučovanie literatúry pre 21. storočie © Silvia Pokrivčáková, Eva Vitézová, Gabriela Magalová, Jana Javorčíková, 2017 Copyright information All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the above mentioned acts, without the prior permission of the author. The right of the author to be identified as the Author has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Act No. 618/2003 on Copyright and Rights Related to Copyright (Slovakia, EU). The text is assumed to contain no proprietary material unprotected by patent or patent application; responsibility for technical content and for protection of proprietary material rests solely with the author and is not the responsibility of the publisher. It is the responsibility of the author to obtain all necessary copyright release permissions for the use of any copyrighted materials in the manuscript prior to the submission. The print version of the book (ISBN 978-80-89864-07-2) by SlovakEdu, n.o. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. -

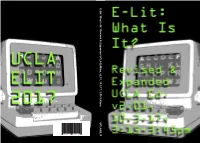

E-Lit: What Is It? Revised & Expanded UCLA Edition, V2.01, 10.3.17, 3:15

E-Lit: What Is It? Revised & Expanded UCLA Edition, v2.01, 10.3.17, 3:15-3:45pm UCLA ELIT 624206 800124 5 E-Lit: What is it? v2.01 October 3, 2017 By UCLA E-LIT 2017 For updates, Follow us on Instagram @uclaelit Electronic Literature: What Is It? V.01 N. Katherine Hayles (UCLA) http://eliterature.org/pad/elp.html Suzy Menazza: “What we have is 200 pages of incomprehensible nonsense” — that’s how UNFCCC Executive Secretary Yvo De Boer commented on the status oF the negotiations early this week during a meeting with NGO representatives here in Bonn, which included The Nature Conservancy. De Boer was reFerring to the new negotiating text For an international climate agreement, which includes a document drafted by the chair of the proceedings back in spring with additions submitted in June by the 192 countries discussing this new agreement. The result is a 199-page-long (and almost unmanageable) document — a combination oF old text, “new paragraphs or subparagraphs,” “alternatives to the original paragraphs” and “special cases” that comprise more than 2,000 brackets and are challenging even the most experienced delegates. Contents 1. Abstract 2. An abstract is a brieF summary oF a research article, thesis, review, conference proceeding, or any in- depth analysis of a particular subject and is often used to help the reader quickly ascertain the paper's purpose.[1] When used, an abstract always appears at the beginning of a manuscript or typescript, acting as the point-of-entry For any given academic paper or patent application.