BRITTEN SINFONIA MARK PADMORE Tenor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T H E P Ro G

Thursday, April 19, 2018, at 7:30 pm m a Art of the Song r g o Mark Padmore , Tenor r P Paul Lewis , Piano e h SCHUMANN Liederkreis (1840) Morgens steh’ ich auf und frage T Es treibt mich hin Ich wandelte unter den Bäumen Lieb Liebchen Schöne Wiege meiner Leiden Warte, warte, wilder Schiffmann Berg’ und Burgen schaun herunter Anfangs wollt’ ich fast verzagen Mit Myrten und Rosen BRAHMS Es liebt sich so lieblich im Lenze Sommerabend Mondenschein (1878) Es schauen die Blumen Meerfahrt Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht Intermission Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano Alice Tully Hall, Starr Theater Adrienne Arsht Stage Great Performers Support is provided by Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser, Audrey Love Charitable Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center. Public support is provided by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. Endowment support for Symphonic Masters is provided by the Leon Levy Fund. Endowment support is also provided by UBS. Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center UPCOMING GREAT PERFORMERS EVENTS: Friday, April 27 at 8:00 pm in David Geffen Hall Los Angeles Philharmonic Gustavo Dudamel, conductor ESA-PEKKA SALONEN: Pollux (New York premiere) VARÈSE: Amériques SHOSTAKOVICH: Symphony No. 5 Pre-concert -

Mark Padmore

` BRITTEN Death in Venice, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden At the centre, there’s a tour de force performance by tenor Mark Padmore as the blocked writer Aschenbach, his voice apparently as fresh at the end of this long evening as at the beginning Erica Jeal, The Guardian, November 2019 Tenor Mark Padmore, exquisite of voice, presents Aschenbach’s physical and spiritual breakdown with extraordinary detail and insight Warwick Thompson, Metro, November 2019 Mark Padmore deals in a masterly fashion with the English words, so poetically charged by librettist Myfanwy Piper, and was in his best voice, teasing out beauty with every lyrical solo. Richard Fairman, The Financial Times, November 2019 Mark Padmore is on similarly excellent form as Aschenbach. Padmore doesn’t do much opera, but this role is perfect for him………Padmore is able to bring acute emotion to these scenes, without extravagance or lyricism, drawing the scale of the drama back down to the personal level. Mark Padmore Gavin Dixon, The Arts Desk, November 2019 Tenor ..It’s the performances of Mark Padmore and Gerald Finley that make the show unmissable. …Padmore……conveys so believably the tragic arc of Aschenbach’s disintegration, from pompous self-regard through confusion and brief ecstatic abandon to physical and moral collapse. And the diction of both singers is so clear that surtitles are superfluous. You will not encounter a finer performance of this autumnal masterpiece. Richard Morrison, The Times, November 2019 BACH St John Passion¸ Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Simon Rattle. Royal Festival Hall, London Mark Padmore has given us many excellent evangelists, yet this heartfelt, aggrieved, intimate take on St John’s gospel narrative, sometimes spiked with penetrating pauses, still seemed exceptional. -

Summer Programs 2015 Highered Temple University Summer Owls

Summer Programs 2015 HigherEd Temple University Summer Owls Leadership Program ● For students completing grades 10 and 11 ● Opportunity to earn 3 college credits in courses in business, media and communication, health professions, or science ● Additional workshops in time management, study skills, and organization ● Held July 13August 2, 2015 ● Cost in 2014 was $4,195 (2015 cost is TBA) and includes the college course, room, board, workshops, and activities ● Students applying by March 17, 2015 will have their $55 application fee waived. Final application deadline is May 1 depending on space ● To apply students must submit a completed application, high school transcript, PSAT/SAT/ACT scores, one letter of recommendation from a teacher of counselor (recommended but not required). ● Students who successfully complete the summer course, apply to Temple, and matriculate as an undergraduate student will receive a $4,000 tuition grant ● For more information and to apply see http://www.temple.edu/summer/leadership/index.html Questions? Contact Dominque Kliger at (215)2042712 or email [email protected] Cornell University Summer College Programs for High School Students ● For students completing grades 1012 ● Opportunity to choose from over 60 courses and earn between 36 college credit ○ Three week session 1: June 20July 11 ○ Three week session 2: July 12August 1 ○ Six week programs: June 20August 4 ● Cost is $6,020 for a three week program and $11,950 for a six week program including classes, room, and board ● Limited financial -

In a World Gone Mad, Can Great Music Help Us See the Light? Orchestra Of

Kings Place 90 York Way London N1 9AG Principal Artists John Butt Sir Mark Elder Iván Fischer Vladimir Jurowski Sir Simon Rattle Sir András Schiff Emeritus Conductors William Christie Sir Roger Norrington In a world gone mad, can great music help us see the light? Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment’s 2020-21 Southbank Centre Season: The Edge of Reason Press Release: 20 February 2020 The Edge of Reason is part four of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment’s (OAE’s) Six Chapters of Enlightenment – concert seasons at Southbank Centre, where the OAE is Resident Orchestra. The series is inspired by the golden age of science and philosophy that gave the Orchestra its name. Crispin Woodhead, OAE Chief Executive, says: “We’re excited to be exploring the great arguments of the 18th century Enlightenment that still grip us today. Where do we find reason? What happens when we get to the edge of it – beyond it, even? What can the big debates and artworks of the past teach us as we stand, apparently, on the threshold of irrationality. The OAE is democratic, run by musicians who like to ask questions. This season, we look at where the boundaries of reason really lie with great works by Handel, Strauss, Schubert and others.’’ For many of their performances, whether in a concert hall or a pub (at its groundbreaking The Night Shift gigs), the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment introduces the music from the stage to share insights and connect with the audience. Playing on instruments the composer would have known and used, the players aim to make old works sound as new and fresh as when they were written. -

Sir James Galway : Living Legend

VOLUME XXXIV , NO . 3 S PRING 2009 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY SIR JAMES GALWAY : LIVING LEGEND Rediscovering Edwin York Bowen Performance Anxiety: A Resource Guide Bright Flutes, Big City: The 37th NFA Convention in New York City THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXIV, N O. 3 S PRING 2009 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 59 New York, New York 7 From the Editor 63 Notes from Around the World 11 Letters to the Editor 60 Contributions to the NFA 13 High Notes 61 NFA News 16 Flute Shots 66 New Products 47 Across the Miles 70 Reviews 53 From the 2009 Convention 78 NFA Office, Coordinators, Program Chair Committee Chairs 58 From Your Convention Director 85 Index of Advertisers 18 FEATURES 18 Sir James Galway: Living Legend by Patti Adams As he enters his 70th year, the sole recipient of the NFA’s 2009 Lifetime Achievement Award continues to perform for, teach, and play with all kinds of people in all forms of mediums throughout the world. 24 The English Rachmaninoff: Edwin York Bowen by Glen Ballard Attention is only now beginning to be paid to long neglected composer York Bowen (1884–1961). 28 York Bowen’s Sonata for Two Flutes, op.103: The Discovery of the Original “Rough and Sketchy Score” by Andrew Robson A box from eBay reveals romance, mystery, and an original score. 24 32 Performance Anxiety: A Resource Guide compiled by Amy Likar, with introduction by Susan Raeburn Read on for an introduction to everything you ever wanted to know (but were afraid to ask) about performance anxiety and related issues. -

2019/20 S E a S

2019/20 SEASON JANUARY - MARCH 2020 2 • Director’s Introduction • 3 We are delighted to welcome the French mezzo-soprano Marianne Crebassa for her Wigmore Hall debut this spring, presenting a programme of her native repertoire alongside two works from the distinguished Turkish pianist, Fazıl Say, who will accompany Crebassa in January. Vijay Iyer continues his contemplations on musicality with two events in January. Ritual Ensemble draws on various musical systems to forge a unity of orchestrated and ecstatic expressions in their music. The following afternoon, Iyer is joined in conversation by Professor Georgina Born for an exchange of ideas traversing the arts, humanities, and social and natural sciences. Our Beethoven celebrations continue with the cycles begun in autumn, including Trio Shaham Erez Wallfisch’s complete piano trios, Jonathan Biss in the complete piano sonatas, and James Ehnes and Andrew Armstrong’s exploration of the composer’s violin sonatas. An evening in March is dedicated to Beethoven’s string trios with Daniel Sepec, Tabea Zimmermann and Jean-Guihen Queyras. The Dover Quartet presents two consecutive concerts in January covering composers from Mozart and Rossini to Hindemith and double bassist Edgar Meyer. Meyer joins the quartet on the Sunday night for a Rossini duet and his own Quintet for strings. In February 2020, Wigmore Hall Learning presents its annual Learning Festival. From Monday 10 to Saturday 22 February, we will explore the concept of Musical Conversations, with a special Bechstein Session event with the Sacconi Quartet to open the festival on 10 February. The celebrated soprano Nelly Miricioiu will be leading what promises to be an insightful masterclass in March, following her lunchtime recital a week before. -

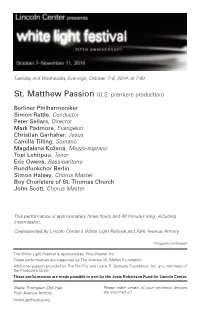

St. Matthew Passion (U.S

10-07 WL St Matthew_GP 9/24/14 12:00 PM Page 1 Tuesday and Wednesday Evenings, October 7–8, 2014, at 7:00 St. Matthew Passion (U.S. premiere production) Berliner Philharmoniker Simon Rattle , Conductor Peter Sellars , Director Mark Padmore , Evangelist Christian Gerhaher , Jesus Camilla Tilling , Soprano Magdalena Kožená , Mezzo-soprano Topi Lehtipuu , Tenor Eric Owens , Bass-baritone Rundfunkchor Berlin Simon Halsey , Chorus Master Boy Choristers of St. Thomas Church John Scott , Chorus Master This performance is approximately three hours and 40 minutes long, including intermission. Co-presented by Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival and Park Avenue Armory (Program continued) The White Light Festival is sponsored by Time Warner Inc. These performances are supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support provided by The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. and members of the Producers Circle. These performances are made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Wade Thompson Drill Hall, Please make certain all your electronic devices Park Avenue Armory are switched off. WhiteLightFestival.org 10-07 WL St Matthew_GP 9/24/14 12:00 PM Page 2 Endowment support is provided by the American Upcoming White Light Festival Events: Express Cultural Preservation Fund. Thursday–Saturday Evenings, October 9–11, MetLife is the National Sponsor of Lincoln Center. at 8:00 in Baryshnikov Arts Center, Jerome Robbins Theater Movado is an Official Sponsor of Lincoln Center. Chalk and Soot (New York premiere) Dance Heginbotham United Airlines is the Official Airline of Lincoln Brooklyn Rider Center. Co-presented with Baryshnikov Arts Center WABC-TV is the Official Broadcast Partner of Friday Evening, October 10, at 7:30 Lincoln Center. -

Kennesaw State University Wind Ensemble David Kehler, Music Director and Conductor

SCHOOL of MUSIC Where PASSION is heard Kennesaw State University Wind Ensemble David Kehler, Music Director and Conductor Performances by students in the KSU Wind Ensemble studios of: Paul Dickinson, KSU Tuba/Euphonium Studio John Lawless, KSU Percussion Studio Douglas Lindsey, KSU Trumpet Studio Hollie Lawing Pritchard, KSU Trombone Studio John Warren, KSU Tuba/Euphonium Studio Wednesday, September 30, 2020 | 7:30 PM Presented virtually from Morgan Concert Hall of the Bailey Performance Center PROGRAM RILEY HODGES (b. 2001) A Group of Owls is Called a Parliament Riley Hodges, piano Brad Cannata, bass Andrew Yi, percussion Sam Brooke, percussion Ben Bouland, percussion VASSILY BRANDT (1869-1923) Country Pictures I. In the Church II. Under a Lime Tree III. At the Feast Sommer Lemcoe, trumpet Cierra Weldin, trumpet Billy Sands, trumpet Matthew Garren, trumpet Jalen Dobson, trumpet 1 SCHOOL of MUSIC Where PASSION is heard JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Vivace from Clarinet Sonata No. 1 in f minor, Opus 120 Jessica Bell, clarinet Eric Jenkins, piano JOHN PSATHAS (b. 1966) Planet Damnation Michael Makrides, timpani JOHN STEVENS (b. 1951) Manhattan Suite I. Rock Zachary Leinberger, euphonium Noah Minch, euphonium Nick Collins, tuba Kobe Greene, tuba MARK GLENTWORTH (b. 1960) Blues for Gilbert Jared Cook, vibraphone ASTOR PIAZZOLLA (1921-1992) Cafe 1930 from Histoire du Tango Olivia Kesler, Eb clarinet Grace Liebl, Bb clarinet John Warren, Bb clarinet Emily O’Connor, bass clarinet 2 SCHOOL of MUSIC Where PASSION is heard EDWARD GREGSON (b. 1945) Concerto for Tuba I. Allegro Deciso Laurenz Oriondo, tuba Eric Jenkins, piano VIENNA TENG (b. 1978) arr. -

Duke University Wind Symphony and KSU Wind Ensemble, "The Duke

Kennesaw State University College of the Arts School of Music presents The Duke Blue Devils meet the KSU Owls Duke University Wind Symphony KSU Wind Ensemble Verena Moesenbichler-Bryant, guest conductor Steven Bryant, special guest composer Monday, October 14, 2013 8:00 p.m Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Seventeenth Concert of the 2013-14 Concert Season Program Duke University Wind Symphony Verena Moesenbichler-Bryant, conductor SCOTT LINDROTH (b. 1958) Spin Cycle (2001) ERIC WHITACRE (b. 1970) October (2000) David Kehler, guest conductor STEVEN BRYANT (b. 1972) Ecstatic Waters (2008) I. Ceremony of Innocence II. Augurs III. The Generous Wrath of Simple Men IV. The Loving Machinery of Justice V. Spiritus Mundi Intermission KSU Wind Ensemble David Thomas Kehler, conductor STEVEN BRYANT Ecstatic Fanfare (2012) JOSEPH SCHWANTNER (b. 1943) … and the mountains rising nowhere (1977) STEVEN BRYANT Idyll (2013) Verena Moesenbichler-Bryant, guest conductor STEVEN BRYANT Solace (2012) Georgia Premiere Program Notes Spin Cycle SCOTT LINDROTH born 1958 Scott Lindroth earned degrees from the Eastman School of Music and the Yale School of Music. He has been the recipient of many awards and fellowships, including the Rome Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Revson Fellowship, an Academy Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Howard Foundation Fellowship. His music has been performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Nether- lands Wind Ensemble, and many other chamber ensembles in the United States and Europe. A recording of Lindroth's chamber music, Human Gestures, is avail- able on CRI, and a recording of Spin Cycle, performed by the University of Michi- gan Wind Ensemble was released on the Equilibrium label in December 2002. -

Download Booklet

THE ENGLISH CONCERT Viola Concerto in G major TWV 51:G9 Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) y I. Largo [3.20] Dall’Abaco, Porpora, Marcello, Tartini & Telemann u II. Allegro [2.43] i III. Andante [3.20] o IV. Presto [3.21] Concerto à più instrumenti in D major Op. 5, No. 6 Evaristo Felice Dall’Abaco (1675-1742) Alfonso Leal del Ojo viola 1 I. Allegro [3.30] 2 II. Aria Cantabile [1.49] Total timings: [68.43] 3 III. Ciaccona [2.41] 4 IV. Rondeau Allegro [0.58] 5 V. Allegro [3.56] HARRY BICKET DIRECTOR / HARPSICHORD Nadja Zwiener & Tuomo Suni violins | Joseph Crouch cello www.signumrecords.com Cello Concerto in G major Nicola Porpora (1686-1768) 6 I. Amoroso [4.57] 7 II. Allegro [4.45] The English Concert is an orchestra which Evaristo Felice Dall’Abaco (1675-1742) was 8 III. Largo [3.37] draws its inspiration from the elite orchestras of born in Verona, the son of a noted guitarist, 9 IV. A tempo giusto [4.09] 18th-century Europe: its members are recruited Damiano Dall’Abaco. Unusually, he appears to Joseph Crouch cello from amongst Europe’s foremost instrumentalists have been a skilled player of both violin and who are led either from the harpsichord or cello, having studied both instruments with Oboe Concerto in D minor Alessandro Marcello (1673-1747) by their principal violinist or Konzertmeister, Giuseppe Torelli. His first post was as a 0 I. Allegro moderato [3.22] just as were the famed court orchestras of violinist in the court orchestra in Modena, q II. -

Sir Colin Davis Discography

1 The Hector Berlioz Website SIR COLIN DAVIS, CH, CBE (25 September 1927 – 14 April 2013) A DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey With special thanks to Philip Stuart © Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey All rights of reproduction reserved [Issue 10, 9 July 2014] 2 DDDISCOGRAPHY FORMAT Year, month and day / Recording location / Recording company (label) Soloist(s), chorus and orchestra RP: = recording producer; BE: = balance engineer Composer / Work LP: vinyl long-playing 33 rpm disc 45: vinyl 7-inch 45 rpm disc [T] = pre-recorded 7½ ips tape MC = pre-recorded stereo music cassette CD= compact disc SACD = Super Audio Compact Disc VHS = Video Cassette LD = Laser Disc DVD = Digital Versatile Disc IIINTRODUCTION This discography began as a draft for the Classical Division, Philips Records in 1980. At that time the late James Burnett was especially helpful in providing dates for the L’Oiseau-Lyre recordings that he produced. More information was obtained from additional paperwork in association with Richard Alston for his book published to celebrate the conductor’s 70 th birthday in 1997. John Hunt’s most valuable discography devoted to the Staatskapelle Dresden was again helpful. Further updating has been undertaken in addition to the generous assistance of Philip Stuart via his LSO discography which he compiled for the Orchestra’s centenary in 2004 and has kept updated. Inevitably there are a number of missing credits for producers and engineers in the earliest years as these facts no longer survive. Additionally some exact dates have not been tracked down. Contents CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF RECORDING ACTIVITY Page 3 INDEX OF COMPOSERS / WORKS Page 125 INDEX OF SOLOISTS Page 137 Notes 1. -

Tansy Davies & Nick Drake Cave

Press release TANSY DAVIES & NICK DRAKE CAVE World premiere The Printworks, Canada Water, London, SE16 7PJ Wednesday 20 June to Saturday 23 June, 7.30pm Saturday 23 June, 2.30pm Tickets on sale 31 January 2018 londonsinfonietta.org.uk The London Sinfonietta, in association with The Royal Opera, presents a landmark new commission by one of the UK’s most exciting composers Tansy Davies and award-winning writer Nick Drake. A bold site-specific opera, Cave is about one man’s quest for survival and courage in a future ruined by climate change. Set in a cave and inspired by their significance across history, the vast space at Printworks provides the perfect venue for this world premiere production. The score, a tapestry of dark, luminous and visceral sounds, conjuring strange spaces full of imagined ancestral spirits, will be expertly performed by tenor Mark Padmore, mezzo- soprano Elaine Mitchener and the London Sinfonietta. Cave is directed by Lucy Bailey and conducted by Geoffrey Paterson. The London Sinfonietta approached Tansy Davies to commission this work as the finale to its 50th Anniversary Season, signifying the ensemble’s commitment to creating innovative, forward-looking new music projects that carry important messages about life in the 21st century. Cave reunites the successful partnership of Davies and Drake following Between Worlds, their operatic response to the events of 9/11 which won the 2016 British Composer Award for Stage Work. Like their first collaboration, Cave tells a story of human suffering balanced by the healing force of the natural world. The central character is a man fleeing from the devastating effects of climate change, who is also on a quest for his lost child.