Volume 41 Number 4 – Fall 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2014

Jan 14 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 160th birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 15 to Jan. 19. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at O'Casey's and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morning, followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's. The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker at the Midtown Executive Club on Thursday evening was James O'Brien, author of THE SCIENTIFIC SHER- LOCK HOLMES: CRACKING THE CASE WITH SCIENCE & FORENSICS (2013); the title of his talk was "Reassessing Holmes the Scientist", and you will be able to read his paper in the next issue of The Baker Street Journal. The William Gillette Luncheon at Moran's was well attended, as always, and the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street (Paul Singleton, Sarah Montague, and Andrew Joffe) entertained their audience with a tribute to an aged Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. The luncheon also was the occasion for Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan Whimsey Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber) honoring the most whimsical piece in The Serpentine Muse last year; the winners (Susan Rice and Mickey Fromkin) received certificates and shared a check for the Canonical sum of $221.17. And Otto Penzler's tradi- tional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportuni- ties to browse and buy. The Irregulars and their guests gathered for the BSI annual dinner at the Yale Club, where John Linsenmeyer proposed the preprandial first toast to Marilyn Nathan as The Woman. -

Ausstellungs-Katalog

----------------------------------------|---------------------------------------- -----------------------------------------p P----------------------------------------- -----------------------------------------p Sherlock Holmes Museum Meiringen/Switzerland Willkommen im Sherlock-Holmes-Museum // Meiringen, Schweiz Welcome to the Sherlock Holmes Museum // Meiringen, Switzerland I--------------------------------\--------------------------------? /--------------------------------\--------------------------------i Einführung Willkommen im Sherlock Bestimmung erhalten. der Welt, war häufig auf den Versuch, sich des De- tal nach Leukerbad. Zu Professor Moriarty Holmes „Das leere Haus“ (veröf- Enthusiasten jeden Alters Holmes-Museum. Das Das Museum steht unter Besuch in der Schweiz. tektivs zu entledigen. In Fuss überquerten sie den an den Rcichcnbachfällen fentlicht 190) erfahren und Herkunft. Neben dem Gebäude, in dem Sie sich dem Patronat der Sher- dieser Geschichte flohen Gemmi-Pass, kamen nach ein, und man glaubte, wir, dass im Todeskampf Museum können Sie die befinden, ist die 1891 ein- lock Holmes Society of So reiste er 189 auch Holmes und sein Freund Kandersteg und erreichten beide hätten nach einem nur Professor Moriarty Sherlock Holmes-Statue geweihte englische Kirche London und von Dame nach Meiringen und an und Biograph Dr. Watson via Interlaken schliesslich verzweifelten Kampf dort den Reichenbachfall hi- und an den Reichenbach- von Meiringen, welche für Jean Conan Doyle (191- die Rcichenbachfälle. Des vor ihrem Erzfeind Profes- Meiringen. ihren Tod gefunden. nabgestürzt ist. Sherlock fällen den Ort des Todes- die zahlreichen englischen 1997), der Tochter von Sir Schreibens von Sherlock sor James Moriarty, dem Holmes gelang es zu ent- kampfes selbst besuchen. Besucher gebaut worden Arthur Conan Doyle. Holmes-Geschichten über- Napoleon des Verbrechens, Hier verbrachten sie die Aber bald überzeugte der kommen und seine Arbeit war. Im Jahr 1991 hat drüssig unternahm er in aus London. Im Zug rei- Nacht vom . -

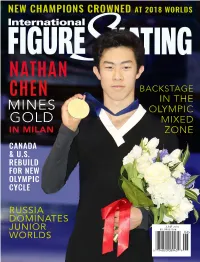

Nathan Chen Backstage in the Mines Olympic Gold Mixed in Milan Zone

NEW CHAMPIONS CROWNED AT 2018 WORLDS NATHAN CHEN BACKSTAGE IN THE MINES OLYMPIC GOLD MIXED IN MILAN ZONE CANADA & U.S. REBUILD FOR NEW OLYMPIC CYCLE RUSSIA DOMINATES JUNIOR JUNE 2018 WORLDS Elegance in Performance www.taniabass.com MADE IN NEW YORK CITY 212-246-2277 No regrets. Patrick Chan oficially announced his retirement from competitive skating on April 16. “Skating has been a big part of my life, and now I’m ready to take what it’s given me and transfer it over into something else, whatever that may be.” Photo: Susan D. Russell Contents 22 Features VOLUME 23 | ISSUE 3 | JUNE 2018 KEEGAN MESSING 6 Canada’s Leading Man BRADIE TENNELL 10 A Season of Firsts RUSSIAN REVOLUTION 12 At World Junior Championships JUMPING JUNIORS 16 New Generation: Quads and Triple Axels SYNCHRO WORLDS 18 Finland Dominates in Sweden BACKSTAGE IN PYEONGCHANG 20 Behind the Scenes in the Olympic Mixed Zone ON THE ON TOP OF THE WORLD COVER Ê 22 Top Names, Rising Stars Take Centre Stage at 2018 World Championships SKATE CANADA REBUILDS 36 End of an Era: What’s Next? U.S. FIGURE SKATING 39 TRANSITIONS Nathan Chen Developing a Youthful Strategy Departments VALLE PHOTO: FLAVIO 4 FROM THE EDITOR 44 FASHION SCORE 32 INNER LOOP 46 TRANSITIONS Reflections From Milan Moving On From the Competitive Ranks 42 THEY SAID IT Quotable Moments 48 QUICKSTEPS from 2018 Worlds COVER PHOTO: ROBIN RITOSS 2 IFSMAGAZINE.COM JUNE 2018 Vanessa James and Morgan Ciprès broke an 18-year drought for France when they captured the bronze medal in pairs at the 2018 World Championships. -

Adream Season

EVGENIA MEDVEDEVA MOVES TO CANADIAN COACH ALJONA SAVCHENKO KAETLYN BRUNO OSMOND MASSOT TURN TO A DREAM COACHING SEASON MADISON CHOCK & SANDRA EVAN BATES GO NORTH BEZIC OF THE REFLECTS BORDER ON HER CREATIVE CAREER Happy family: Maxim Trankov and Tatiana Volosozhar posed for a series of family photos with their 1-year-old daughter, Angelica. Photo: Courtesy Sergey Bermeniev Adam Rippon and his partner Jena Johnson hoisted their Mirrorball Trophies after winning “Dancing with the Stars: Athlete’s Edition” in May. Photo: Courtesy Rogers Media/CityTV Contents 24 Features VOLUME 23 | ISSUE 4 | AUGUST 2018 EVGENIA MEDVEDEVA 6 Feeling Confident and Free MADISON CHOCK 10 & EVAN BATES Olympic Redemption A CREATIVE MIND 14 Canadian Choreographer Sandra Bezic Reflects on Her Illustrious Career DIFFERENT DIRECTIONS 22 Aljona Savchenko and Bruno Massot Turn to Coaching ON THE KAETLYN OSMOND COVER Ê 24 Celebrates a Dream Season OLYMPIC INDUCTIONS 34 Champions of the Past Headed to Hall of Fame EVOLVING ICE DANCE HUBS 38 Montréal Now the Hot Spot in the Ice Dance World THE JUNIOR CONNECTION 40 Ted Barton on the Growth and Evolution of the Junior Grand Prix Series Kaetlyn Osmond Departments 4 FROM THE EDITOR 44 FASHION SCORE All About the Men 30 INNER LOOP Around the Globe 46 TRANSITIONS Retirements and 42 RISING STARS Coaching Changes NetGen Ready to Make a Splash 48 QUICKSTEPS COVER PHOTO: SUSAN D. RUSSELL 2 IFSMAGAZINE.COM AUGUST 2018 Gabriella Papadakis drew the starting orders for the seeded men at the French Open tennis tournament, and had the opportunity to meet one of her idols, Rafael Nadal. -

Pulkinen (USA), Kostiukovich/Ialin (RUS) Lead After First Day of World Junior Championships

March 7, 2019 Zagreb, CRO Pulkinen (USA), Kostiukovich/Ialin (RUS) lead after first day of World Junior Championships Camden Pulkinen (USA) and Polina Kostiukovich/Dmitrii Ialin (RUS) lead in the Junior Men’s and Junior Pairs events respectively after their Short Programs as the ISU World Junior Figure Skating Championships opened Wednesday in Zagreb, Croatia. A total of 180 skaters from 44 ISU members have been entered for the Championships: 38 Men, 46 Ladies, 17 Pair Skating couples and 31 Ice Dance couples. Pulkinen (USA) wins competitive Junior Men’s Short Program Camden Pulkinen (USA) took the lead in a very competitive Junior Men’s Short Program as the ISU World Junior Figure Skating Championships opened in Zagreb (CRO) on Wednesday. Tomoki Hiwatashi (USA) placed second followed by Italy’s Daniel Grassl. The top 10 skaters are separated by just over five points and a lot can happen in the Free Skating on Thursday. Skating to “Oblivion” by Astor Piazzolla, Pulkinen produced a triple Lutz-triple toeloop combination and triple flip as well as two level-four spins and footwork to set a new season's best of 82.41 points. “I’m very happy about the result and how I skated,” the 18-year-old said. “I know there was a little mistake with the [flying camel] spin on levels, so I could have been even better than I was today. The competition was fantastic. A lot of people skated clean programs and I am very happy that I was able to end up on top today and I’m looking forward to the free skating.” Hiwatashi’s performance to “Cry Me a River” by Arthur Hamilton featured a triple Axel, triple flip and triple Lutz-triple toe. -

Sherlock Holmes C Ontents

March 1999 Volume 3 Number 1 Sherlock Holmes "Your merits should be publicly recognized" (STUD) Stix - Shaw Bolo Tie Comes to Minnesota very special acquisition occurred "Sterling, Hand Engraved Original by Ed in New York during the 1999 Morgan @1983" Contents annual Sherlock Holmes birthday weekend. Dorothy Stix, wife of The Shaw legacy lives on too, as Dorothy the late Tom Stix (who, as 'Wiggins' headed continues to buy more Sherlochan books. Stix - Shaw Bolo Tie the Baker Street Irregulars for eleven years), "I can't stop," said Dorothy. She also keeps presented Friends President Richard Sveum an eye on the papers for Sherlocluan refer- with a bolo tie that had belonged to her ences and trims them out. She said, in a 100 Years Ago husband, and had originally belonged to brief interview, that she's, "been doing it for n John Bennett Shaw. 25 years and just can't quit." More than once she would catch somethng that John After seeing a similar bolo tie belonging to had missed and he would compliment her 50 Years Ago their longtime friend, Saul Cohen, Dorothy on her "good eye." All of the new material 3 Shaw had an artist in Taos, New Mexico she is accumulating will, "eventually go to create one for John. After John's death, Minnesota," she said. From the President Dorothy was going through his desk and 4 found the bolo. She felt that John had We would lke to offer a heartfelt "thank you" intended to give it to Tom and so she did - to Dorothy Stix and the Stix family for pre- An Update from the with the understanding that upon his death senting d-us specd item to the Collections Collections it would join the rest of John's collection at and also to Dorothy Shaw for continuing to 4 the University of Minnesota. -

Christopher and Barbara Roden Donate Shaw-Tracy Letters To

March 2002 D S O F N Volume 6 Number 1 E T Acquisitions I H R E ue Vizoskie, A.S.H., donated copies of two booklets that she compiled and edited. Teas and Toasts with the 3 Garridebs F was completed for the 10th Anniversary Picnic and Victorian Tea that is held annually by the 3 Garridebs, and it includes toasts and recipes of items that have been made for the picnics. Her second booklet, Sherlockians Aboard: S Their Adventures on and Memoirs of The Sherlock Holmes Society of London Golden Jubilee Cruise 2001, contains essays by a number of Americans and Canadians who participated in the cruise. Michael Doyle donated a copy of It Commenced with Two…, The Story of Mary Ann Doyle, written by Bonaventure Brennan, Sherlock Holmes RSM. Mr. Doyle purchased this book and had it signed by the author for presentation to the Collections. Mary Ann Doyle, COLLECTIONS the great-aunt of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, is noted in this book as a companion to Catherine McAuley, founder of the order of the Sisters of Mercy in 1831. “Your merits should be publicly recognized” (STUD) Don Hobbs presented Curator Tim Johnson with a copy of the Lithuanian magazine Veidas, which carried an article titled “Views of a Maniac Collector” and an accompanying picture of Don with Dorothy Rowe Shaw. While pursuing his own mani- ac collecting of foreign editions several years ago, Don was asked to write an article which he titled “Collecting Sherlock Contents Christopher and Barbara Roden Donate Holmes.” This ran in a different Lithuanian magazine in April 1997. -

2019/2020 ANNUAL REPORT SKATE ONTARIO WELCOME MESSAGE Lisa Alexander, Executive Director Karen Butcher, President

SKATE ONTARIO 2019/2020 ANNUAL REPORT SKATE ONTARIO WELCOME MESSAGE Lisa Alexander, Executive Director Karen Butcher, President The annual report is an opportunity to reflect on a season full of triumphs, development and of course, unexpected change and challenges. This skating season, unfortunately cut short, came with many accomplishments from Ontario skaters at all levels. Ontario skaters showed their pride and skated with TABLE OF CONTENTS heart at our Sectional Championships and again at the Skate Canada Challenge where they were the largest team. Ontario hosted the Canadian Tire National Skating Championships in January, bringing together athletes, coaches, volunteers and parents from across the country. It was a great display of collective hospitality and Welcome Message 3 fantastic results from Ontario athletes and volunteers. In addition to impressive international results, at the national level Ontario skaters were on the podium in every Clubs & Schools 4 - 5 event and won two Novice, two Junior and three Senior National titles. Skater Development 6 - 7 From a clubs and skating schools perspective, it is wonderful to see growth and hard work in all areas of the province. Thank you to the clubs for all of your engagement Coaches 8 - 9 and input with Assessment Days, Performance and Development Opportunities and participation in initiatives such as the STAR 6 - Gold Roadshow, Event Info Sessions Officials 10 - 11 and the CanSkate Excellence Program. Although it was disappointing the season ended early and new events like Bring ON the Fun! were cancelled, it was exciting to see how engaged everyone has been adapting to change. Your ideas, enthusiasm and energy have never been more important and appreciated as we navigate this new Synchronized Skating 12 - 13 reality. -

Ice Dance Won by 0.01 Points and Substitute Gogolev (CAN) Steals the Show

December 7, 2018 Vancouver, Canada Ice Dance won by 0.01 points and substitute Gogolev (CAN) steals the show Shevchenko/Eremenko (RUS) clinch Junior Dance victory by 0.01 points Sofia Shevchenko/Igor Eremenko clinched victory in the Junior Ice Dance event by the slimmest of margins and led Russia to a podium sweep at the ISU Junior Grand Prix Final in Vancouver (CAN) on Friday. Arina Ushakova/Maxim Nekrasov took the silver and the bronze went to Elizaveta Khudaiberdieva/Nikita Nazarov. Dancing to “Intro” by Onuka Witchdoctor and “Camo & Krooked Lijo” by Alina Orlova, Shevchenko/Eremenko delivered a strong performance, collecting a level four for the twizzles, combination spin and two lifts as well as a level three for the footwork sequences. The team from Moscow posted a new season’s best with 102.93 points. They were ranked second in the Free Dance but held on to first place with 170.66 points total. “We’re in a kind of shock now, and we go around glassy-eyed. We haven’t realized it yet. Sport is such a thing – one time you’re at the top and next time you’re at the bottom. This is our first major victory,” Shevchenko said. “It was so close with 0.01 points difference. It was worth the fight,” Eremenko noted. “We worked really hard for this competition, and we really wanted to show the kind of skate that we are able to show to our coaches during practice. Competition always brings worries and stress, it is a little different than training - which is why we were striving to relax and to show what we are truly capable of. -

Hits Triple Axel and Quad Lutz to Make History at ISU Junior Grand Prix in Lake Placid

September 4, 2019 Lake Placid, USA Liu (USA) hits triple Axel and quad Lutz to make history at ISU Junior Grand Prix in Lake Placid Alysa Liu (USA) made history by becoming the first female skater to land a triple Axel and a quadruple jump in one program at the ISU Junior Grand Prix event in Lake Placid. Shun Sato (JPN) secured the second consecutive gold medal for the Japanese junior men on the circuit this year while the Russian pairs, led by Apollinariia Panfilova/Dmtiry Rylov, continued their dominance by sweeping the podium. Favorites Avonley Nguyen/Vadym Kolesnik (USA) struck gold in the Ice Dance event. The winners have made a big step on the Road to Torino towards the qualification for the ISU Junior Grand Prix Final. Liu (USA) makes history, scores runaway victory Liu easily dominated the Junior Ladies and scored a runaway victory with 208.10 over Yeonjeong Park (KOR/186.58 points) and Anastasia Tarakanova (RUS/179.29 points) to break the Russian stronghold on the discipline. The American is the first non-Russian Lady to win a Junior Grand Prix event since 2016. Liu and Park debuted on the ISU junior circuit while Tarakanova is a veteran and was in the Junior Grand Prix Final the past two seasons. Liu led following a clean Short Program. She opened her Free Skating to “Illumination” by Jennifer Thomas with a triple Axel-double toeloop and a quadruple Lutz – and is the first woman two perform a triple Axel and a quad in one program. The 14-year-old followed up with six more triples, but she missed her second triple Axel. -

Breaking Ice Mar 2016 FR

Les dernières nouvelles fraîches de Kockelscheuer March 2016 Chers patineurs, chers parents, Ce mois sera marqué par un événement très spécial, pour notre Club, mais également pour la communauté internationale du patinage artistique. Comme chaque année, l’Union Luxembourgeoise de Patinage et le club Hiversport – Luxembourg Patinage organisent leur traditionnelle Coupe du Printemps, compétition qui pour la cinquième année figure sur la liste officielle de l’International Skating Union, l’organe officiel des plus grandes compétitions internationales de patinage artistique. Du 11 au 13 mars 2016, des patineurs venant du monde entier concourront sur la glace de la patinoire de Kockelscheuer, dans les catégories novice à senior, pour gagner leur place sur le podium d’une compétition au niveau très élevé. L’organisation de la Coupe du Printemps a permis aux clubs luxembourgeois d’affirmer leur professionnalisme au niveau mondial et de faire rayonner localement la pratique du patinage artistique, et chaque édition de la Coupe s’est traduite par un succès grandissant. Cette année encore, nous avons le plaisir d'accueillir plus de 120 patineurs venant de 26 pays différents dont le Japon, le Canada, Hong Kong, Singapour, le Kirghizistan, la France, la Belgique, l'Allemagne et bien sûr le Luxembourg représenté par les talentueuses Mara Wagner, Chloé Villedey, Gemma Marshall et Tereza Kravalova. Nous accueillerons des grands noms du patinage dont Takahito Mura qui a terminé 5ème aux récents Championnats des 4 Continents à Taïwan, Rin Niyata, deuxième du Junior Grand Prix de Torun en Pologne, Joshi Helgesson, 9ième des derniers Championnats d'Europe et vainqueur de la dernière Coupe du Printemps, Alexander Majorov qui a terminé 14ième des Jeux Olympiques de Sochi. -

Canadian Figure Skating Championships Championnats Canadiens De Patinage Artistique

Canadian Figure Skating Championships Championnats canadiens de patinage artistique Canadian Figure Skating Championships Championnats canadiens de patinage artistique Men/hommes Senior Junior Novice 1905 1 Ormond B Haycock (Minto SC) 1906 1 Ormond B Haycock (Minto SC) 1907 No competition - Minto Skating Club rink destroyed by fire/Pas de compétition.La patinoire du Club de patinage Minto a été détruite par un incendie 1908 1 Ormond B Haycock (Minto SC) 1909 no competition/pas de compétition 1910 1 Douglas H Nelles (Minto SC) 1911 1 Ormond B Haycock (Minto SC) 2 J Cecil McDougall 1912 1 Douglas H Nelles (Minto SC) 1913 1 Philip Chrysler (Minto SC) 2 Norman Scott (Minto SC) 1914 1 Norman Scott (Montreal WC) 2 Philip Chrysler (Minto SC) 1915-1919 No competitions held due to World War I | Compétition annulée à cause de la Première Guerre mondiale 1920 1 Duncan Hodgson (Montreal WC) 2 John Machado (Minto SC) 3 Melville Rogers (Toronto SC) 1921 1 Norman Scott (Montreal WC) 2 Duncan Hodgson (Montreal WC) 3 Melville Rogers (Toronto SC) 19221 Duncan Hodgson (Montreal WC) 2 Melville Rogers (Toronto SC)} 3 John Machado (Minto SC) 1923 1 Melville Rogers (Toronto SC) 2 John Machado (Minto SC) 3 Norman Gregory (Montreal WC) 19241 John Machado (Minto SC) 2 Montgomery Wilson (Toronto SC) 3 Norman Gregory (Montreal WC) Canadian Figure Skating Championships / 1 Championnats canadiens de patinage artistique Canadian Figure Skating Championships Championnats canadiens de patinage artistique Men/hommes Senior Junior Novice 1925 1 Melville Rogers (Toronto