Story Rich Game Project: Liekko and the Stolen Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

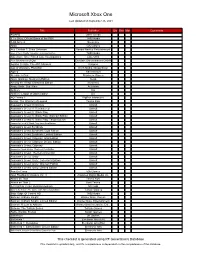

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Dual-Forward-Focus

Scroll Back The Theory and Practice of Cameras in Side-Scrollers Itay Keren Untame [email protected] @itayke Scrolling Big World, Small Screen Scrolling: Neural Background Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Thalamus Relay sensory signals to the cerebral cortex (e.g. vision, motor) Amygdala Emotional reactions of fear and anxiety, memory regulation and conditioning "fight-or-flight" regulation Familiar visual patterns as well as pattern changes may cause anxiety unless regulated Vestibular System Balance, Spatial Orientation Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Natural image stabilizer Conflicting sensory signals (Visual vs. Vestibular) may lead to discomfort and nausea* * much worse in 3D (especially VR), but still effective in 2D Scrolling with Attention, Interaction and Comfort Attention: Use the camera to provide sufficient game info and feedback Interaction: Make background changes predictable, tightly bound to controls Comfort: Ease and contextualize background changes Attention The Elements of Scrolling Interaction Comfort Scrolling Nostalgia Rally-X © 1980 Namco Scramble © 1981 Jump Bug © 1981 Defender © 1981 Konami Hoei/Coreland (Alpha Denshi) Williams Electronics Vanguard -

Ethics at Play in Undertale: Rhetoric, Identity and Deconstruction

Ethics at Play in Undertale: Rhetoric, Identity and Deconstruction Frederic SERAPHINE The University of Tokyo – ITASIA Program Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, JAPAN +81-3-5841-8769 Seraphine[at]g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the effect of ethical – and unethical – actions of the player on their perception of the self towards game characters within Toby Fox’s (2015) independent Role Playing Game (RPG) Undertale, a game often perceived as a pacifist text. With a focus on the notions of guilt and responsibility in mind, a survey with 560 participants from the Undertale fandom was conducted, and thousands of YouTube comments were scraped to better understand how the audience who watched or played the different routes of the game, refer to its characters. Through the joint analysis of the game’s semiotics, survey data, and data scraping, this paper argues that, beyond the rhetorical nature of its story, Undertale is operating a deconstruction of the RPG genre and is harnessing the emotional power of gameplay to evoke thoughts about responsibility and raise the player’s awareness about violence and its consequences. Keywords rhetoric, ethics, deconstruction, pacifism, violence, character, avatar, meta-storytelling INTRODUCTION There are some artistic experiences that stick with us for a very long time, aesthetic memories, that one may put between their first kiss and their first fight. For many of its players, a game like Undertale seems to fall into this category. Because its story puts the player in the situation of making choices that affect dramatically the course of the narrative, and the survival of its characters, it seems people who played this game grow an attachment to its fictional characters comparable to the attachment to a friend in their real life. -

Full Game Development

CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION FULL GAME DEVELOPMENT June 2021 CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION PROUD TO WORK WITH STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION EXTENSIVE IP EXPERIENCE We carefully study the IP's history and lore and follow every small detail to avoid costly mistakes. We create new content in precisely defined limitations and work closely with IP holders for timely approvals. STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION TECHNOLOGY FOCUS EXPERTISE Our experience with Unity along with certification from Playstation to Xbox, Nintendo and Apple Arcade allow us to provide powerful solutions for our customers. Focus: Mobile & cross-platform development / C# Platforms: Mobile / Switch / Cloud CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION CREATIVE APPROACH CORNERSTONES Game Design Expertise Align creative vision with your business goals with thought-through game design, game economy design, and level design for optimal pacing and enjoyment. And we have experts in all three areas. GAME IDEA & UNIQUE MECHANICS SEARCHING Producer's Vision During the vision formation & pre-production phase we test We strive to deliver an exceptional gaming experience: our game’s market fit to avoid mistakes during development, producer keeps a hand on pulse to see that the game’s get a full grasp on the scope of the project, foresee the catchy, or funny, or scary just as you wanted it, and works super fast. complications and liabilities of the game. Art Direction How to stand out on the market, or how to make all the details look consistent? How colors influence the mood of a player? You guessed it: our art director will be responsible that your game not only looks good, but feels right. -

Opera Acquires Yoyo Games, Launches Opera Gaming

Opera Acquires YoYo Games, Launches Opera Gaming January 20, 2021 - [Tuck-In] Acquisition forms the basis for Opera Gaming, a new division focused on expanding Opera's capabilities and monetization opportunities in the gaming space - Deal unites Opera GX, world's first gaming browser and popular game development engine, GameMaker - Opera GX hit 7 million MAUs in December 2020, up nearly 350% year-over-year DUNDEE, Scotland and OSLO, Norway, Jan. 20, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- Opera (NASDAQ: OPRA), the browser developer and consumer internet brand, today announced its acquisition of YoYo Games, creator of the world's leading 2D game engine, GameMaker Studio 2, for approximately $10 million. The tuck-in acquisition represents the second building block in the foundation of Opera Gaming, a new division within Opera with global ambitions and follows the creation and rapid growth of Opera's innovative Opera GX browser, the world's first browser built specifically for gamers. Krystian Kolondra, EVP Browsers at Opera, said: "With Opera GX, Opera had adapted its proven, innovative browser tech platform to dramatically expand its footprint in gaming. We're at the brink of a shift, when more and more people start not only playing, but also creating and publishing games. GameMaker Studio2 is best-in-class game development software, and lowers the barrier to entry for anyone to start making their games and offer them across a wide range of web-supported platforms, from PCs, to, mobile iOS/Android devices, to consoles." Annette De Freitas, Head of Business Development & Strategic Partnerships, Opera Gaming, added: "Gaming is a growth area for Opera and the acquisition of YoYo Games reflects significant, sustained momentum across both of our businesses over the past year. -

Video Gaming and Death

Untitled. Photographer: Pawel Kadysz (https://stocksnap.io/photo/OZ4IBMDS8E). Special Issue Video Gaming and Death edited by John W. Borchert Issue 09 (2018) articles Introduction to a Special Issue on Video Gaming and Death by John W. Borchert, 1 Death Narratives: A Typology of Narratological Embeddings of Player's Death in Digital Games by Frank G. Bosman, 12 No Sympathy for Devils: What Christian Video Games Can Teach Us About Violence in Family-Friendly Entertainment by Vincent Gonzalez, 53 Perilous and Peril-Less Gaming: Representations of Death with Nintendo’s Wolf Link Amiibo by Rex Barnes, 107 “You Shouldn’t Have Done That”: “Ben Drowned” and the Uncanny Horror of the Haunted Cartridge by John Sanders, 135 Win to Exit: Perma-Death and Resurrection in Sword Art Online and Log Horizon by David McConeghy, 170 Death, Fabulation, and Virtual Reality Gaming by Jordan Brady Loewen, 202 The Self Across the Gap of Death: Some Christian Constructions of Continued Identity from Athenagoras to Ratzinger and Their Relevance to Digital Reconstitutions by Joshua Wise, 222 reviews Graveyard Keeper. A Review by Kathrin Trattner, 250 interviews Interview with Dr. Beverley Foulks McGuire on Video-Gaming, Buddhism, and Death by John W. Borchert, 259 reports Dying in the Game: A Perceptive of Life, Death and Rebirth Through World of Warcraft by Wanda Gregory, 265 Perilous and Peril-Less Gaming: Representations of Death with Nintendo’s Wolf Link Amiibo Rex Barnes Abstract This article examines the motif of death in popular electronic games and its imaginative applications when employing the Wolf Link Amiibo in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017). -

Cole, Tom. 2021. ”Moments to Talk About”: Designing for the Eudaimonic Gameplay Experience

Cole, Tom. 2021. ”Moments to Talk About”: Designing for the Eudaimonic Gameplay Experience. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/29689/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] “Moments to Talk About”: Designing for the Eudaimonic Gameplay Experience Thomas Cole Department of Computing Goldsmiths, University of London April 2020 (corrections December 2020) Thesis submitted in requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract This thesis investigates the mixed-affect emotional experience of playing videogames. Its contribution is by way of a set of grounded theories that help us understand the game players’ mixed-affect emotional experience, and that support ana- lysts and designers in seeking to broaden and deepen emotional engagement in videogames. This was the product of three studies: First — An analysis of magazine reviews for a selection of videogames sug- gested there were two kinds of challenge being presented. Functional challenge — the commonly accepted notion of challenge, where dexterity and skill with the controls or strategy is used to overcome challenges, and emotional chal- lenge — where resolution of tension within the narrative, emotional exploration of ambiguities within the diegesis, or identification with characters is overcome with cognitive and affective effort. -

Immersion and Worldbuilding in Videogames

Immersion and Worldbuilding in Videogames Omeragić, Edin Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:664766 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-01 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – prevoditeljski smjer i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Edin Omeragić Uranjanje u virtualne svjetove i stvaranje svjetova u video igrama Diplomski rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2019. Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – prevoditeljski smjer i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Edin Omeragić Uranjanje u virtualne svjetove i stvaranje svjetova u video igrama Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2019. University of J.J. Strossmayer in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: -

Creación De Una Simbología Para Un Videojuego

TFG CREACIÓN DE UNA SIMBOLOGÍA PARA UN VIDEOJUEGO Presentado por Carlos Mercé Vila Tutora: María Lorenzo Hernández Facultat de Belles Arts de Sant Carles Grado en Bellas Artes Curso 2016-2017 Simbología para videojuego. Carlos Mercé 2 RESUMEN Mi trabajo de fin de grado consiste en la realización de un videojuego indie 2D de género acción, aventura, RPG(1) abarcando su producción artística y la creación de un prototipo. Para la elaboración de la historia, ambientación, caracterización y personalización de los personajes precisaré referentes previos, desde lo relativo a otros videojuegos del mismo género, series de anime con las que siento afinidad, pasando por un estudio de mitologías y religiones del mundo, centrándome en la cultura precolombina inca. A partir del anterior estudio me introduciré en la parte práctica del proyec- to, la elaboración de bocetos y concept art para plasmar las ideas y poder trabajar sobre ellas. Después de eso, el siguiente paso consiste en diseñar el juego con un estilo Pixel Art: Personajes, fondos, efectos, menús, etc. La elección de esta estética se debe por la afinidad que me produce trabajar con el 2D y por la nostalgia que me da al recordar a los videojuegos con los que disfrutaba de niño. La última fase del trabajo consistirá en guardar el trabajo de forma ordenada y con el formato de comprensión adecuado para proporcionarlo al encargado de la programación del videojuego, pasando el turno de elaborarlo y darlo a probar a algunas personas escogidas anticipadamente para comprobar la línea de dificultad. Palabras clave: Videojuegos, Pixel Art, dioses incas, 2D, iconografía religiosa, indie, mecánicas. -

Whats the Best Way to Store Downloads On

whats the best way to store downloads on ps4 What Is PlayStation Plus, and Is It Worth It? If you have a PlayStation 4, Sony’s PlayStation Plus service is required to play multiplayer games online. A subscription costs $10 per month or $60 per year. PlayStation Plus also includes additional benefits, like free games every month and members-only discounts on some digital games. What Is PlayStation Plus? PlayStation Plus is Sony’s online gaming subscription service for the PlayStation 4. It’s required to play online multiplayer games on the PlayStation 4. Whether you’re playing a competitive multiplayer game with people you’ve never met or a co-operative game with a friend who lives a few blocks away, you’ll need PS Plus to do it. Sony has also added some additional features to this service. Only PlayStation Plus members can upload their game saves, storing them online where they can be accessed on another console. PlayStation Plus members get some free games every month, and they also get access to some bonus sales on digital games. PlayStation 4 vs. PlayStation 3 and Vita. On the PlayStation 4, Sony’s PS Plus works exactly like Xbox Live Gold on the Xbox One. It’s required for online multiplayer gaming. However, if you have a PlayStation 3 or PlayStation Vita, PlayStation Plus is not required for online multiplayer gaming. You can play online games for free. PS Plus still gives you access to some free games and sales if you have a PS3 or Vita, but it’s much less critical than it is on a PS4. -

Chorst Resume 2020.Pdf

CAMERON HORST TECHNICAL SKILLS Game Developer – Technical Designer Languages C#, Editor Tools, Google Apps Script / Sheets Automation 924 N Ogden Dr Unit 6, West Hollywood, CA 90046 Software Unity, Maya, Substance, Adobe CC, Blender, Houdini, UE4, GitHub / (916) 747-5036 ◊ [email protected] Source Control https://twitter.com/CH_CGI/ Skills Game Programming, Game Mechanics, UX / UI Design, XR Development, 3D Mathematics WORK EXPERIENCE PROJECTS Artists of the Industry September 2017 - Present Marriott - Virtual Tour Platform (PC, iOS) Lead Designer / Unity Developer . Developed virtual tour platform . Lead developer on interactive experiences for augmented and virtual reality . Interface design, UI / UX development from concept through production. Built editor tools and automated production . Designed experiences for platforms and technologies including: Mobile AR, . Integrated tools with back-end media server 3dof and 6dof VR, 360 Domes, RFID, and 360 Video. Contributed to early concept design and built rapid prototypes to iteratively- United Airlines - VR Virtual Tour test ideas. (Mobile VR, Oculus Rift) . Met with prospective clients to demonstrate our products and to deliver . Developed interactive tour of data center proposals. Interfaced with current clients throughout development for . Designed real-time motion graphics regular reviews. Built VR run-time editor tools for object placement . Optimized production by developing production pipelines and building Unity editor tools and workflows integrating with back-end media servers. Built Coca-Cola - Connections Terminal (PC) automated spreadsheets for asset and data tracking. Built networking application for leadership conference Pawmigo June 2017 – December 2017 . Utilized RFID badges for attendee identification Unity Engineer / Developer . Integrated with back-end database . Ported Cat Sorter VR from SteamVR to OVR for publishing on the Oculus .