Power Play and Performance in Harajuku

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Acculturation Process for Kaigaishijo: a Qualitative Study of Four Japanese Students in an American School

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 The acculturation process for kaigaishijo: A qualitative study of four Japanese students in an American school Linda F. Harkins College of William & Mary - School of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Personality and Social Contexts Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Harkins, Linda F., "The acculturation process for kaigaishijo: A qualitative study of four Japanese students in an American school" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539618735. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-6dp2-fn37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORM ATION TO U SE R S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

A 5 Day Tokyo Itinerary

What To Do In Tokyo - A 5 Day Tokyo Itinerary by NERD NOMADS NerdNomads.com Tokyo has been on our bucket list for many years, and when we nally booked tickets to Japan we planned to stay ve days in Tokyo thinking this would be more than enough. But we fell head over heels in love with this metropolitan city, and ended up spending weeks exploring this strange and fascinating place! Tokyo has it all – all sorts of excellent and corky museums, grand temples, atmospheric shrines and lovely zen gardens. It is a city lled with Japanese history, but also modern, futuristic neo sci- streetscapes that make you feel like you’re a part of the Blade Runner movie. Tokyo’s 38 million inhabitants are equally proud of its ancient history and culture, as they are of its ultra-modern technology and architecture. Tokyo has a neighborhood for everyone, and it sure has something for you. Here we have put together a ve-day Tokyo itinerary with all the best things to do in Tokyo. If you don’t have ve days, then feel free to cherry pick your favorite days and things to see and do, and create your own two or three day Tokyo itinerary. Here is our five day Tokyo Itinerary! We hope you like it! Maria & Espen Nerdnomads.com Day 1 – Meiji-jingu Shrine, shopping and Japanese pop culture Areas: Harajuku – Omotesando – Shibuya The public train, subway, and metro systems in Tokyo are superb! They take you all over Tokyo in a blink, with a net of connected stations all over the city. -

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

Clothing Fantasies: a Case Study Analysis Into the Recontextualization and Translation of Subcultural Style

Clothing fantasies: A case study analysis into the recontextualization and translation of subcultural style by Devan Prithipaul B.A., Concordia University, 2019 Extended Essay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication (Dual Degree Program in Global Communication) Faculty of Art, Communication and Technology © Devan Prithipaul 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Devan Prithipaul Degree: Master of Arts Title: Clothing fantasies: A case study analysis into the recontextualization and translation of subcultural style Program Director: Katherine Reilly Sun-Ha Hong Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor ____________________ Katherine Reilly Program Director Associate Professor ____________________ Date Approved: August 31, 2020 ii Abstract Although the study of subcultures within a Cultural Studies framework is not necessarily new, what this research studies is the process of translation and recontextualization that occurs within the transnational migration of a subculture. This research takes the instance of punk subculture in Japan as a case study for examining how this subculture was translated from its original context in the U.K. The frameworks which are used to analyze this case study are a hybrid of Gramscian hegemony and Lacanian psychoanalysis. The theoretical applications for this research are the study of subcultural migration and the processes of translation and recontextualization. Keywords: subculture; Cultural Studies; psychoanalysis; hegemony; fashion communication; popular communication iii Dedication Glory to God alone. iv Acknowledgements “Ideas come from pre-existing ideas” was the first phrase I heard in a university classroom, and this statement is ever more resonant when acknowledging those individuals who have led me to this stage in my academic journey. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

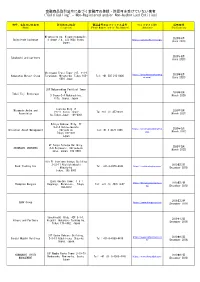

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) Miyakojima-ku, Higashinodamachi, 2020年6月 SwissTrade Exchange 4-chōme−7−4, 534-0024 Osaka, https://swisstrade.exchange/ (June 2020) Japan 2020年6月 Takahashi and partners (June 2020) Shiroyama Trust Tower 21F, 4-3-1 https://www.hamamatsumerg 2020年6月 Hamamatsu Merger Group Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105- Tel: +81 505 213 0406 er.com/ (June 2020) 0001 Japan 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. -

TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP JR Yamanote

JR Yamanote Hibiya line TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP Ginza line Chiyoda line © Tokyo Pocket Guide Tozai line JR Takasaka Kana JR Saikyo Line Koma line Marunouchi line mecho Otsuka Sugamo gome Hanzomon line Tabata Namboku line Ikebukuro Yurakucho line Shin- Hon- Mita Line line A Otsuka Koma Nishi-Nippori Oedo line Meijiro Sengoku gome Higashi Shinjuku line Takada Zoshigaya Ikebukuro Fukutoshin line nobaba Todai Hakusan Mae JR Joban Asakusa Nippori Line Waseda Sendagi Gokokuji Nishi Myogadani Iriya Tawara Shin Waseda Nezu machi Okubo Uguisu Seibu Kagurazaka dani Inaricho JR Shinjuku Edo- Hongo Chuo gawa San- Ueno bashi Kasuga chome Naka- Line Higashi Wakamatsu Okachimachi Shinjuku Kawada Ushigome Yushima Yanagicho Korakuen Shin-Okachi Ushigome machi Kagurazaka B Shinjuku Shinjuku Ueno Hirokoji Okachimachi San-chome Akebono- Keio bashi Line Iidabashi Suehirocho Suido- Shin Gyoen- Ocha Odakyu mae Bashi Ocha nomizu JR Line Yotsuya Ichigaya no AkihabaraSobu Sanchome mizu Line Sendagaya Kodemmacho Yoyogi Yotsuya Kojimachi Kudanshita Shinano- Ogawa machi Ogawa Kanda Hanzomon Jinbucho machi Kokuritsu Ningyo Kita Awajicho -cho Sando Kyogijo Naga Takebashi tacho Mitsu koshi Harajuku Mae Aoyama Imperial Otemachi C Meiji- Itchome Kokkai Jingumae Akasaka Gijido Palace Nihonbashi mae Inoka- Mitsuke Sakura Kaya Niju- bacho shira Gaien damon bashi bacho Tameike mae Tokyo Line mae Sanno Akasaka Kasumi Shibuya Hibiya gaseki Kyobashi Roppongi Yurakucho Omotesando Nogizaka Ichome Daikan Toranomon Takaracho yama Uchi- saiwai- Hachi Ebisu Hiroo Roppongi Kamiyacho -

Willieverbefreelikeabird Ba Final Draft

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning Fashion Subcultures in Japan A multilayered history of street fashion in Japan Ritgerð til BA-prófs í japönsku máli og menningu Inga Guðlaug Valdimarsdóttir Kt: 0809883039 Leðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorkellsdóttir September 2015 1 Abstract This thesis discusses the history of the street fashion styles and its accompanying cultures that are to be found on the streets of Japan, focusing on the two most well- known places in Tokyo, namely Harajuku and Shibuya, as well as examining if the economic turmoil in Japan in the 1990s had any effect on the Japanese street fashion. The thesis also discusses youth cultures, not only those in Japan, but also in North- America, Europe, and elsewhere in the world; as well as discussing the theories that exist on the relation of fashion and economy of the Western world, namely in North- America and Europe. The purpose of this thesis is to discuss the possible causes of why and how the Japanese street fashion scene came to be into what it is known for today: colorful, demiurgic, and most of all, seemingly outlandish to the viewer; whilst using Japanese society and culture as a reference. Moreover, the history of certain street fashion styles of Tokyo is to be examined in this thesis. The first chapter examines and discusses youth and subcultures in the world, mentioning few examples of the various subcultures that existed, as well as introducing the Japanese school uniforms and the culture behind them. The second chapter addresses how both fashion and economy influence each other, and how the fashion in Japan was before its economic crisis in 1991. -

“Down the Rabbit Hole: an Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion”

“Down the Rabbit Hole: An Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion” Leia Atkinson A thesis presented to the Faculty of Graduate and Post-Doctoral Studies in the Program of Anthropology with the intention of obtaining a Master’s Degree School of Sociology and Anthropology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Leia Atkinson, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract An ethnographic work about Japanese women who wear Lolita fashion, based primarily upon anthropological field research that was conducted in Tokyo between May and August 2014. The main purpose of this study is to investigate how and why women wear Lolita fashion despite the contradictions surrounding it. An additional purpose is to provide a new perspective about Lolita fashion through using interview data. Fieldwork was conducted through participant observation, surveying, and multiple semi-structured interviews with eleven women over a three-month period. It was concluded that women wear Lolita fashion for a sense of freedom from the constraints that they encounter, such as expectations placed upon them as housewives, students or mothers. The thesis provides a historical chapter, a chapter about fantasy with ethnographic data, and a chapter about how Lolita fashion relates to other fashions as well as the Cool Japan campaign. ii Acknowledgements Throughout the carrying out of my thesis, I have received an immense amount of support, for which I am truly thankful, and without which this thesis would have been impossible. I would particularly like to thank my supervisor, Vincent Mirza, as well as my committee members Ari Gandsman and Julie LaPlante. I would also like to thank Arai Yusuke, Isaac Gagné and Alexis Truong for their support and advice during the completion of my thesis. -

Description of Fences

Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Description of Fences フェンスの説明 / Description des obstacles Fence 1 – RIO 2016 EQUO JUMPINDV----------QUAL000100--_03B 1 Report Created TUE 3 AUG 2021 17:30 Page 1/14 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Fence 2 – Tokyo Skyline Tōkyō Sukai Tsurī o 東京スカイツリ Sumida District, Tokyo The new Tokyo skyline has been eclipsed by the Sky Tree, the new communications tower in Tokyo, which is also the highest structure in all of Japan at 634 metres, and the highest communications tower in the world. The design of the superstructure is based on the following three concepts: . Fusion of futuristic design and traditional beauty of Japan, . Catalyst for revitalization of the city, . Contribution to disaster prevention “Safety and Security”. … combining a futuristic and innovating design with the traditional Japanese beauty, catalysing a revival of this part of the city and resistant to different natural disasters. The tower even resisted the 2011 earthquake that occurred in Tahoku, despite not being finished and its great height. EQUO JUMPINDV----------QUAL000100--_03B 1 Report Created TUE 3 AUG 2021 17:30 Page 2/14 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Fence 3 – Gold Repaired Broken Pottery Kintsugi, “the golden splice” The beauty of the scars of life. The “kintsugi” is a centenary-old technique used in Japan which dates of the second half of the 15th century. -

Memoirs of a Geisha Arthur Golden Chapter One Suppose That You and I Were Sitting in a Quiet Room Overlooking a Gar-1 Den, Chatt

Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html Memoirs Of A Geisha Arthur Golden Chapter one Suppose that you and I were sitting in a quiet room overlooking a gar-1 den, chatting and sipping at our cups of green tea while we talked J about something that had happened a long while ago, and I said to you, "That afternoon when I met so-and-so . was the very best afternoon of my life, and also the very worst afternoon." I expect you might put down your teacup and say, "Well, now, which was it? Was it the best or the worst? Because it can't possibly have been both!" Ordinarily I'd have to laugh at myself and agree with you. But the truth is that the afternoon when I met Mr. Tanaka Ichiro really was the best and the worst of my life. He seemed so fascinating to me, even the fish smell on his hands was a kind of perfume. If I had never known him, I'm sure I would not have become a geisha. I wasn't born and raised to be a Kyoto geisha. I wasn't even born in Kyoto. I'm a fisherman's daughter from a little town called Yoroido on the Sea of Japan. In all my life I've never told more than a handful of people anything at all about Yoroido, or about the house in which I grew up, or about my mother and father, or my older sister-and certainly not about how I became a geisha, or what it was like to be one. -

Tokyo Orientation 2017 Ajet

AJET News & Events, Arts & Culture, Lifestyle, Community TOKYO ORIENTATION 2017 Stay Cool and Look Clean - how to be fashionably sweaty Find the Fun - how to get involved with SIGs (and what they exactly are) Studying Japanese - how to ganbaru the benkyou on your sumaho Shinju-who? - how to have fun and understand Shinjuku Hot and Tired in Tokyo - how to spend those orientation evenings The Japanese Lifestyle & Culture Magazine Written by the International Community in Japan1 CREDITS & CONTENT HEAD EDITOR HEAD OF DESIGN & HEAD WEB EDITOR Lilian Diep LAYOUT Nadya Dee-Anne Forbes Ashley Hirasuna ASSITANT HEAD EDITOR ASSITANT WEB EDITOR Lauren Hill COVER PHOTO Amy Brown Shantel Dickerson SECTION EDITORS SOCIAL MEDIA Kirsty Broderick TABLE OF CONTENTS John Wilson Jack Richardson Michelle Cerami Shantel Dickerson PHOTO Hayley Closter Shantel Dickerson Nicole Antkiewicz COPY EDITORS Verushka Aucamp Jasmin Hayward ART & PHOTOGRAPHY Tresha Barrett Tresha Barrett Hannah Varacalli Bailey Jo Josie Jasmin Hayward Abby Ryder-Huth Hannah Martin Sabrina Zirakzadeh Shantel Dickerson Jocelyn Russell Illaura Rossiter Micah Briguera Ashley Hirasuna This magazine contains original photos used with permission, as well as free-use images. All included photos are property of the author unless otherwise specified. If you are the owner of an image featured in this publication believed to be used without permission, please contact the Head of Graphic Design and Layout, Ashley Hirasuna, at ashley. [email protected]. This edition, and all past editions of AJET CONNECT,