Cultural Conceptions of Hiv/Aids in Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

067 Risky Business

Risky Business: The Duque Government’s Approach to Peace in Colombia Latin America Report N°67 | 21 June 2018 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The FARC’s Transition to Civilian Life ............................................................................. 3 III. Rural Reform and Illicit Crop Substitution ...................................................................... 7 IV. Transitional Justice .......................................................................................................... 11 V. Security Threats ................................................................................................................ 14 VI. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 19 APPENDICES A. Colombian Presidential Run-off Results by Department ................................................ 21 B. Map of Colombia ............................................................................................................. 22 C. Acronyms ......................................................................................................................... -

Perspectives: an Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle De González, and Thomas Mcilwraith

Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology Edited by Nina Brown, Laura Tubelle de González, and Thomas McIlwraith 2017 American Anthropological Association American Anthropological Association 2300 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1301 Arlington, VA 22201 ISBN: 978–1-931303–55–2 http://www.perspectivesanthro.org This book is a project of the Society for Anthropology in Community Colleges (SACC) http://sacc.americananthro.org/ and our parent organization, the American Anthropological Association (AAA). Please refer to the website for a complete table of contents and more information about the book. PUBLIC ANTHROPOLOGY Robert Borofsky, Hawaii Pacific University, Center for a Public Anthropology [email protected] http://www.publicanthropology.org/ LEARNING OBJECTIVES As an example of public anthropology (following the model • Explain how the structure of academic of the Kahn Academy), Dr. Borofsky has created short careers, topical specialization, and 10–15 minute videos on key topics in anthropology for in- writing styles contribute to difficulty troductory students. All 28 videos are available from the with communicating findings from Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology academic anthropology to a wider website. public. • Identify examples of anthropological INTRODUCTION research that has contributed to the public good. Was Julie Andrews right when (in the Sound of Music) • Define public anthropology and she sang, “Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place distinguish it from academic to start?” Should authors follow her advice in writing text- anthropology and applied book chapters by, at the beginning, explaining the organiza- anthropology. tion of the chapter so readers will know what to expect and • Assess the factors that contribute be able to follow the chapter’s themes clearly? I cannot sing to a desire for public engagement in Do Re Me half as well as Julie Andrews. -

Risky Business Northern California Authority Northern California

Municipal Pooling Municipal Pooling Authority Risky Business Northern California Authority Northern California How to Get Your Sleep Back… (Continued from Page 1) WINTER IS COMING—PREPARE Risky Business Fall Here are a few of the recommended ways to blunt the impact of COVID-19 2020 disruption on your sleep: YOUR HOME FOR THE COLD! • Get up at the same time each day – This is important even on the week- ends, so your brain and body get into a rhythm. Avoid sleeping in or napping Before the weather gets too cold, you should How to Get Your Sleep Back on Track in the afternoon. protect your house and family from the ele- • Get outside early – Natural sunlight tells our brain it is daytime so your brain ments. Here are some essential areas to check: can start preparing to help you perform your best and help you to wind down at the same time at night Roof COVID-19 has disrupted nearly every aspect of • Keep a routine – A routine will aid productivity, improve mood and expend the Look for missing shingles, cracked flashing, everyone’s life, and sleep is no exception. But be careful, says same amount of energy each day to best earn quality sleep onset at the same and broken overhanging tree limbs. UH clinical psychologist Carolyn Ievers-Landis, PhD -- the time each night. • Stay physically active – Exercising early in the day also helps to earn sleep Check the chimney for mortar deterioration irregular sleep schedules created by COVID-19 can have a at the same time each night. -

Visionary's Dream Led to Risky Business Opaque Deals, Accounting Sleight of Hand Built an Energy Giant and Ensured Its Demise

Visionary's Dream Led to Risky Business Opaque Deals, Accounting Sleight of Hand Built an Energy Giant and Ensured Its Demise By Peter Behr and April Witt Washington Post Staff Writers Sunday, July 28, 2002; Page A01 First of five articles For Vince Kaminski, the in-house risk-management genius, the fall of Enron Corp. began one day in June 1999. His boss told him that Enron President Jeffrey K. Skilling had an urgent task for Kaminski's team of financialanalysts. A few minutes later, Skilling surprised Kaminski by marching into his office to explain. Enron's investment in a risky Internet start-up called Rhythms NetConnections had jumped $300 million in value. Because of a securities restriction, Enron could not sell the stock immediately. But the company could and did count the paper gain as profit. Now Skilling had a way to hold on to that windfall if the tech boom collapsed and the stock dropped. Much later, Kaminski would come to see Skilling's command as a turning point, a moment in which the course of modern American business was fundamentally altered. At the time Kaminski found Skilling's idea merely incoherent, the task patently absurd. When Kaminski took the idea to his team -- world-class mathematicians who used arcane statistical models to analyze risk -- the room exploded in laughter. The plan was to create a private partnership in the Cayman Islands that would protect -- or hedge -- the Rhythms investment, locking in the gain. Ordinarily, Wall Street firms would provide such insurance, for a fee. But Rhythms was such a risky stock that no company would have touched the deal for a reasonable price. -

Medical-Anthropology-2015.Pdf

Princeton University Department of Anthropology Spring 2015 MEDICAL ANTHROPOLOGY ANT 335 M/W 11:00 am- 12:20 pm Lewis Library 120 Instructor: Professor João Biehl ([email protected]) Lecturer: Bridget Purcell ([email protected]) Graduate Student Assistants: Kessie Alexandre ([email protected] Thalia Gigerenzer ([email protected]) Course Description Medical Anthropology is a critical and people-centered investigation of affliction and therapeutics. It draws from approaches in anthropology and the medical humanities to understand the body- environment-medicine interface in a cross-cultural perspective. How do social processes determine disease and health in individuals and collectivities? How does culture surface in the seeking of treatment and the provision of medical care? What role do medical technologies and public interventions play in health outcomes? Which values inform medical theory and practice, and how might the humanities deepen our understanding of the realities of disease and care? In the first half of the course, we will discuss topics such as: the relation of illness, subjectivity, and social experience; the logic of witchcraft; the healing efficacy of symbols and rituals; the art of caregiving and moral sensibility. We will also probe the reach and relevance of concepts such as the normal and the pathological, body techniques, discipline and normalization, medicalization, the nocebo and placebo effects, the mindful body, and the body politic. In the second half of the course, we will explore how scientific -

Risky Business: Rethinking Lateral Partner Hiring

Risky Business Rethinking Lateral Hiring February 2019 BROUGHT TO YOU BY Table of Contents About The Authors..................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology............................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 Status Quo: Big Hires, Big Opportunities ................................................................................ 8 Everyone Hires ......................................................................................................................... 8 Hiring Laterally to Strengthen Existing Practice Areas .............................................................. 9 Lateral Hiring as a Way to Bring in New Clients and Support Growth ..................................... 10 Lateral Hiring to Support Expansion ....................................................................................... 12 Succession Planning .............................................................................................................. 14 Key Takeaways: Lateral Hiring Supports a Range of Goals for Law Firms ............................. 14 Risk, Reward, and Failure........................................................................................................ 15 The Cost of Acquiring Lateral Partners .................................................................................. -

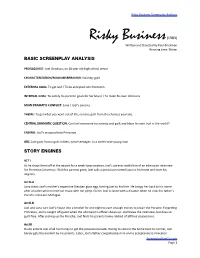

Risky Business Script Analysis

Risky Business Screenplay Analysis Risky Business (1983) Wri$en and Directed by Paul Brickman Running 7me: 96min BASIC SCREENPLAY ANALYSIS PROTAGONIST: Joel Goodson, an 18 year old high school senior CHARACTERIZATION/MAIN MISBEHAVIOR: Naivety; guilt EXTERNAL GOAL: To get laid / To be accepted into Princeton INTERNAL GOAL: To sasfy his parents’ goals for his future / To make his own decisions MAIN DRAMATIC CONFLICT: Lana / Joel’s parents THEME: To get what you want out of life, remove guilt from the chances you take. CENTRAL DRAMATIC QUESTION: Can Joel overcome his naivety and guilt and blaze his own trail in the world? ENDING: Joel’s accepted into Princeton. ARC: Joel goes from a guilt-ridden, naive teenager, to a street-wise young man. STORY ENGINES ACT I As he drops them off at the airport for a week-long vacaon, Joel’s parents no7fy him of an admission interview for Princeton University. With his parents gone, Joel calls a pros7tute named Lana to his home and loses his virginity. Act II-A Lana steals Joel’s mother’s expensive Steuben glass egg, forcing Joel to find her. He brings her back to his home aer an altercaon turned car chase with her pimp, Guido. Joel is faced with a disaster when he sinks his father’s Porsche into Lake Michigan. Act II-B Joel and Lana turn Joel’s house into a brothel for one night to earn enough money to repair the Porsche. Forgeng Princeton, Joel is caught off guard when the admission’s officer shows up. Joel blows the interview, but does so guilt-free. -

INVISIBLE WOUNDS: RETHINKING RECOGNITON in DECOLONIAL NARRATIVES of ILLNESS and DISABILITY by CAROLYN MARGARET UREÑA a Dissert

INVISIBLE WOUNDS: RETHINKING RECOGNITON IN DECOLONIAL NARRATIVES OF ILLNESS AND DISABILITY By CAROLYN MARGARET UREÑA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Comparative Literature Written under the direction of Ann Jurecic And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2017 © 2017 Carolyn Margaret Ureña ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Invisible Wounds: Rethinking Recognition in Decolonial Narratives of Illness and Disability By CAROLYN MARGARET UREÑA Dissertation Director: Ann Jurecic Working at the interface of literary studies, decolonial theory, and disability studies, my dissertation draws on literature and film across a variety of genres, including fiction by Ralph Ellison, Gabriel García Márquez, Toni Morrison, and Junot Díaz, to demonstrate how literary narratives about illness and disability contribute to understanding racial formations and ameliorating colonial wounds. The dissertation develops a critical framework for understanding the ways in which a sustained encounter between critical race studies, disability studies, and the medical humanities can generate new conceptions of health and healing. I accomplish this through a reassessment of the writings of decolonial theorist Frantz Fanon, a physician who used narrative case studies and ethnography to illuminate the imbrication of race, illness, and disability. By introducing a decolonial perspective to the study of narratives of illness and disability, this project not only challenges the medical humanities and disability studies to consider the experience of race and the effects of colonialism, but also foregrounds questions of disability and illness within the fields of race theory and postcolonial studies, where they have until now received minimal scholarly attention. -

Paul Farmer Is One of the Most Extraordinary People I Have Ever Met

“Paul Farmer is one of the most extraordinary people I have ever met. A brilliant doctor and teacher, he tirelessly works for the poorest of the poor, insisting that they deserve the very best care that is available. He not only changes individual lives, but massive systems, proving against overwhelming objections that his methods are not only what Christian compassion demands, but that they bring about effective cures. Jennie Weiss Block will make you fall in love not only with Paul, but with the beloved people to whom he is so passionately committed. This is not a book you can put back on the shelf after reading; it will move you to take the next step in your own commitment to accompany the poorest in our world.” — Barbara Reid, OP Professor of New Testament Studies Catholic Theological Union “It is rare that readers get to explore the lives of legendary people while they are still with us making this book a precious gift. One of the greatest physician-scholar-activist servants in American history, Paul Farmer is a powerful model of service to the poor. The world has much to learn from his life and witness. For anyone with a heart for the vulnerable, the poor, and the underserved, this thoughtful new text about an extraordinary human being is an inspiration and must-read.” — Bryan Stevenson Director of Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy “Some say that the devil is in the details, but in the life of Paul Farmer, there’s grace in those details! Whether he’s living in Haiti, Liberia, Rwanda, or Cambridge, channeling the corporal works into weapons of mass salvation, or running with the preferential option for the poor, Paul’s life exudes the call that’s so tangible in these pages. -

In His Compelling Book, Farmer Captures the Central Dilemma of Our Times—The Increasing Disparities of Health and Well-Being Within and Among Societies

PRAISE FOR PAUL FARMER’S PATHOLOGIES OF POWER “In his compelling book, Farmer captures the central dilemma of our times—the increasing disparities of health and well-being within and among societies. While all member countries of the United Nations denounce the gross viola- tions of human rights perpetrated by those who torture, murder, or imprison without due process, the insidious violations of human rights due to structural violence involving the denial of economic opportunity, decent housing, or ac- cess to health care and education are commonly ignored. Pathologies of Power makes a powerful case that our very humanity is threatened by our collective failure to end these abuses.” ROBERT S. LAWRENCE, President of Physicians for Human Rights and Professor of Preventive Medicine, Johns Hopkins University “Pathologies of Power is a passionate critique of conventional biomedical ethics by one of the world’s leading physician-anthropologists and public intellectu- als. Farmer’s on-the-ground analysis of the relentless march of the AIDS epi- demic and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among the imprisoned and the sick- poor of the world illuminates the pathologies of a world economy that has lost its soul.” NANCY SCHEPER-HUGHES, author of Death without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil “Wedding medicine and anthropology, painstaking clinical and field observation with rigorous conceptual elaboration, Farmer gives us that most rare of books: one that opens both our minds and hearts. Pathologies of Power uses the prism of public health to illuminate the structural forces that decide the ‘right to sur- vive’ on the global stage. -

Second Opinion February 2018

3/5/2018 Second Opinion: Newsletter of the Society for Medical Anthropology Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS Newsletter of the Society for Medical Anthropology View this email in your browser February 2018 / Vol. 6, Issue 1 In This Issue: From the SMA President Congratulations to 2017 SMA Award Recipients! SMA-SPA Box Lunch Mentoring Receives High Praise Updates from MASA SMA Welcomes New Anthropology News Liaisons CPF: 2018 Sections Editions of Anthropology News SMA Call for Proposals: 2018 AAA Annual Meeting Society for Applied Anthropology 2018 Annual Meeting Past President EJ Sobo's Parting Words: A Focus on Readiness for Rapid Response Book Announcements General Announcements Facebook Twitter Website From the SMA President Dear SMA members, I’m pleased to write for the first time in Second Opinion as President of the Society for Medical Anthropology. First, I’d like to share with you some new business that we discussed at our board meeting last December. We voted to create the Hazel Weidman Award for Exemplary Service, which will be presented every other year starting in 2019, named after the driving force behind the creation of the predecessors of Medical Anthropology Quarterly and the SMA. We also voted to organize the third SMA conference in 2019, this time in a Latin American country. Our purpose is to acknowledge and engage the intellectual production coming from that region, particularly in three areas: 1) critical epidemiology, social medicine, and critical medical anthropology, 2) indigenous movements and intercultural care in health, and 3) sexual and reproductive health and rights. However, the conference would not be bounded to any particular region; instead, it would have a focus on entangled and shared histories and on the work of displacements and decentering. -

Bridget Hanna

BRIDGET HANNA Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute Asia Center Department of Sociology and Anthropology Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Northeastern University Harvard University [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Cambridge, MA Social Anthropology, 2014 Dissertation Toxic Relief: Science, Uncertainty, and Medicine after Bhopal Committee: Arthur Kleinman, Ajantha Subramanian, Sheila Jasanoff Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA Courses Environmental Health, Epidemiology & Biostatistics, 2009-10 A.M. Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Social Anthropology, 2008 B.A. Bard College, Annandale, NY Cultural Anthropology, 2004 Thesis The School of the Future: The Social Construction of an Environmental Hazard in the Post-industrial Fringe POSTDOCTORAL AFFILIATIONS & OTHER RESEARCH POSITIONS Postdoctoral Research Associate, Social Science & Environmental Health Research Institute, Department of Sociology & Anthropology, Northeastern University, 2014-2015; 2016. Designed survey and research materials for environmental health data privacy project with Silent Spring Institute; developed socio-exposome research project; participated in SSEHRI research group, STS training program, and sociological research training. Visiting Scholar, Asia Center, Harvard University, 2014-2016. Visiting Scholar, Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado, 2012-2014 Research Assistant to Professor Arthur Kleinman, Harvard Department of Social Medicine 2008;