Drawing, Interpretation and Costume Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

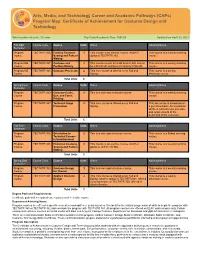

Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology

Arts, Media, and Technology Career and Academic Pathways (CAPs) Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology Total number of units: 23 units Top Code/Academic Plan: 1006.00 Updated on April 25, 2021 Fall Odd Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 366 Fantasy Costume 3 This course is an elective course. Another This course is a weekly morning Course Sewing and Pattern option is TECTHTR 365. course. Making Program/GE TECTHTR 367 Costume and 3 This course counts as a GE Area C Arts course This course is a weekly morning Course Fashion History for LACCD GE and Area C1 Arts for CSU GE. course. Program/GE TECTHTR 345 Costume Practicum 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This course is a weekly Course Spring. afternoon course. Total Units 8 Spring Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 363 Costume Crafts, 3 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a weekly morning Course Dye, and Fabric course. Printing Program TECTHTR 342 Technical Stage 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This lab course is scheduled on Course Production Spring. a per show basis. An orientation will be held to discuss schedule and requirements at the beginning of the semester. Total Units 5 Fall Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 305 Orientation to 2 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a Friday morning Course Technical Careers course. in Entertainment Program TECTHTR 365 Historical Costume 3 This course is an elective course. -

GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] +1(347)636.6681 AWARDS + HONORS SKILLS ASHLEY LAW EDUCATION WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL

ASHLEY LAW GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] http://ashleylaw.info +1(347)636.6681 linkedin.com/in/ashley-law instagram.com/_ashleylaw EDUCATION AWA RDS SKILLS SCHOOL OF VISUAL + GRAPHIS (GOLD) SOFTWARE ARTS (New York) NEW TALENT ANNUAL InDesign HONORS BFA Design Editorial Design “Zine”- Illustrator 2017–2019 2018 Photoshop PremierePro AfterEffects SCHOOL OF THE SVA HONOR’S LIST Sketch ART INSTITUTE OF 2017–2018 CHICAGO (Chicago) Fine Art + Visual CAPABILITIES & Critical Studies SAIC MERIT Branding 2013–2015 SCHOLARSHIP Content Production 2013–2015 Identity System Interactive/Digital Design Print + Editorial Design Typography WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL Junior Graphic Design for the GCL team focusing on CREATIVE LAB Designer creative direction of special projects, 06. 2019 - Present (New York) under the direction of Shu Hung and John Jay. Campaigns include collaborations (i.e. Lemaire, JW Anderson, Alexander Wang) and new store openings. MATTE PROJECTS Design Intern Designing client proposals, print, 01. 2019–04. 2019 (New York) digital & social collateral for marketing agency. Worked on projects for Cartier, The Chainsmokers, Moda Operandi & MATTE events (FNT, BLACK-NYC, Full Moon Festival, La Luna). PYT OPERANDI Creative Project Associate for artist management & creative 03–06. 2016 Associate project development company with emphasis (Hong Kong) in film, photography, exhibitions, project & business development consulting. CLOVER GROUP Intimates Design Designed for leading global manufacturer INTL LIMITED. Intern of intimate apparel, emphasis on the 08–10. 2015 (Hong Kong) Victoria’s Secret account. Visually detailed creative direction, identity & design of project pitches. Similar work for clients including Wacoal, Aerie, Lane Bryant. GIORGIO ARMANI Menswear R&D Shadowed Manager of R&D department OPERATIONS Intern for Menswear at HK Armani Corporate 06–09. -

Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association

For internal use only Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association. All rights reserved. Student(s): School: Selection: Troupe: 4 | Superior 3 | Excellent 2 | Good 1 | Fair SKILLS Above standard At standard Near standard Aspiring to standard SCORE Job Understanding Articulates a broad Articulates an Articulates a partial Articulates little and Interview understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the Articulation of the costume costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role designer’s role and specific and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; job responsibilities; thoroughly presents adequately presents and inconsistently presents does not explain an presentation and and explains the explains the executed and explains the executed executed design, creative explanation of the executed executed design, creative design, creative decisions, design, creative decisions decisions or collaborative design, creative decisions, decisions, and and collaborative process. and/or collaborative process. and collaborative process. collaborative process. process. Comment: Design, Research, A well-conceived set of Costume designs, Incomplete costume The costume designs, and Analysis costume designs, research, and script designs, research, and research, and analysis Design, research and detailed research, and analysis address the script analysis of the script do not analysis addresses the thorough script artistic and practical somewhat address the address the artistic and artistic and practical needs analysis clearly address needs of the production artistic and practical practical needs of the (given circumstances) of the artistic and practical and support the unifying needs of the production production or support the the script to support the needs of production and concept. -

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

Theatre (THEA)

Kent State University Catalog 2021-2022 1 THEA 11724 FUNDAMENTALS OF PRODUCTION LABORATORY II: THEATRE (THEA) PROPS AND SCENIC ART 1 Credit Hour Practice in theatre production techniques in the area of properties and THEA 11000 THE ART OF THE THEATRE (DIVG) (KFA) 3 Credit Hours scenic art. Using the life-centered nature of theatre as a medium of analysis, this Prerequisite: Special approval. course is designed to develop critically engaged audience members Corequisite: THEA 11722. who are aware of the impact, significance and historical relevance of the Schedule Type: Laboratory interconnection between culture and theatre performance. Contact Hours: 2 lab Prerequisite: None. Grade Mode: Standard Letter Schedule Type: Lecture Attributes: CTAG Performing Arts, TAG Arts and Humanities Contact Hours: 3 lecture THEA 11732 FUNDAMENTALS OF PRODUCTION II: COSTUMES, Grade Mode: Standard Letter LIGHTING AND PROJECTIONS 2 Credit Hours Attributes: Diversity Global, Kent Core Fine Arts, Transfer Module Fine An introduction to professional theatre production principles and Arts practices in the areas of costumes, lighting and projections. THEA 11100 MAKING THEATRE: CULTURE AND PRACTICE 2 Credit Prerequisite: Special approval. Hours Schedule Type: Lecture Overview of theatre practices through creative experiential learning. The Contact Hours: 2 lecture focus and course content combines practical and cultural experiences Grade Mode: Standard Letter and culminates with a performance event that provides a solid foundation Attributes: CTAG Performing Arts in the artistic process and an identity for the first-year theatre student. THEA 11733 FUNDAMENTALS OF PRODUCTION LABORATORY III: Prerequisite: Special approval. COSTUMES 1 Credit Hour Schedule Type: Lecture Practice in theatre production techniques in the area of costumes. -

Bsc-Costume-Design-And-Fashion.Pdf

PERIYAR UNIVERSITY PERIYAR PALKALAI NAGAR SALEM – 636011 DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM Syllabus for B.SC. COSTUME DESIGN AND FASHION ( SEMESTER PATTERN ) ( For Candidates admitted in the Colleges affiliated to Periyar University from 2017 - 2018 onwards ) PERIYAR UNIVERSITY REGULATIONS I. CONDITION Candidates seeking admission to the first year degree of Bachelor of Science in Costume Design and Fashion shall be required to have passed in any higher secondary course examination of the state board/CBSE/ICSE. Pass in any Fashion/ Costume/Textile/Apparel related Diploma course is eligible to admit in direct second year of this UG Course. II. DURATION The course for the degree of Bachelor Of Science Costume Design and Fashion shall extend over a period of three academic years - 6 Semesters and each semester normally consisting of 90 working days or 450 Hours. III. ELIGIBILITY FOR THE DEGREE A candidate shall be eligible for the degree of Bachelor Of Science Costume Design And Fashion, if he/she has satisfactorily undergone the prescribed courses of the study for a period not less than 6 semesters in an institution approved by the university has passed the prescribed examinations in all the 6 Semesters. IV. SUBJECT OF STUDY The subjects of the study for the B.Sc., Costume Design and Fashion and the syllabus for the subjects are given in the annexure. V. REQUIREMENT OF EXAMINATION The theory examinations will be conducted for 3 Hours by the university in the subjects prescribed for all the semesters in the month of November & April every year. The practical examinations will be conducted for 3 Hours by the university in all the subjects prescribed in every semester. -

DRAWING COSTUMES, PORTRAYING CHARACTERS Costume Sketches and Costume Concept Art in the Filmmaking Process

Laura Malinen 2017 DRAWING COSTUMES, PORTRAYING CHARACTERS Costume sketches and costume concept art in the filmmaking process MA thesis Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture Department of Film, Television and Scenography Master’s Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television Major in Costume Design 30 credits Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Sofia Pantouvaki and Satu Kyösola for the invaluable help I got for this thesis. I would also like to thank Nick Keller, Anna Vilppunen and Merja Väisänen, for sharing their professional expertise with me. Author Laura Malinen Title of thesis Drawing Costumes, Portraying Characters – Costume sketches and costume concept art in the filmmaking process Department Department of Film, Television and Scenography Degree programme Master’s Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television. Major in Costume Design Year 2017 Number of pages 85 Language English Abstract This thesis investigates the various types of drawing used in the process of costume design for film, focusing on costume sketches and costume concept art. The research question for this thesis is ‘how and why are costume sketches and costume concept art used when designing costumes for film?’ The terms ‘costume concept art’ and ‘costume sketch’ have largely been used interchangeably. My hypothesis is that even though costume sketch and costume concept art have similarities in the ways of usage and meaning, they are, in fact, two separate, albeit interlinked and complementary terms as well as two separate types of professional expertise. The focus of this thesis is on large-scale film productions, since they provide the most valuable information regarding costume sketches and costume concept art. -

(Purple Masque) Scenic Design Checklist

SECOND STAGE (PURPLE MASQUE) SCENIC DESIGN CHECKLIST MANDATORY ATTENDANCE AT: All director/designer meetings Minimum of two meetings with Faculty Scenic Designer: one prior to preliminary deadline, and one prior to final deadline. All production meetings Minimum of one run-through rehearsal prior to crew watch Crew watch All technical and dress rehearsals Strike Any conflicts with attending the above meetings/rehearsals must be cleared ahead of time with the faculty designer and the director. IMPORTANT INFORMATION There is a very limited time frame for installation and painting of scenery in the masque. Therefore, it is extremely important for you to be organized prior to your load in date. Some things to consider: You will be working late nights/weekends during load in and tech, so plan ahead to have papers/homework/studying done ahead of time. “I had to write a paper so the set didn’t get done until opening night” is not a valid excuse. EVERYTHING needs to be built prior to load in. It is best if you can paint pieces beforehand, also. If you are building a large unit, make sure it will fit through all doors. Large units in pieces should be “dry fit” in the scene shop to make sure they assemble as planned. Make sure you arrange for help ahead of time. People will be more willing to assist you if they know a week or two beforehand. This is not just your show. Having the scenery unfinished not only affects the actors, but the lighting and costume designs as well. ROUGH DESIGNS Rough designs will include research image boards of conceptual, architectural and detail inspirations for the set. -

Introduction

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS THE OLIVE WONG PROJECT PERFORMANCE COSTUME DESIGN RESEARCH GUIDE INTRODUCTION COSTUME DESIGN AND PERFORMANCE WRITTEN AND EDITED BY AILEEN ABERCROMBIE The New York Public Library for the Perform- newspapers, sketches, lithographs, poster art ing Arts, located in Lincoln Center Plaza, is and photo- graphs. In this introduction, I will nestled between four of the most infuential share with you some of Olive’s selections from performing arts buildings in New York City: the NYPL collection. Avery Fisher Hall, Te Metropolitan Opera, the Vivian Beaumont Teater (home to the Lincoln There are typically two ways to discuss cos- Center Teater), and David H. Koch Teater. tume design: “manner of dress” and “the history Te library matches its illustrious location with of costume design”. “Manner of dress” contextu- one of the largest collections of material per- alizes the way people dress in their time period taining to the performing arts in the world. due to environment, gender, position, economic constraints and attitude. Tis is essentially the The library catalogs the history of the perform- anthropological approach to costume design. ing arts through collections acquired by notable Others study “the history of costume design”, photographers, directors, designers, perform- examining the way costume designers interpret ers, composers, and patrons. Here in NYC the the manner of dress in their time period: where so many artists live and work we have the history of the profession and the profession- an opportunity, through the library, to hear als. Tis discussion also talks about costume sound recording of early flms, to see shows designers’ backstory, their process, their that closed on Broadway years ago, and get to relationships and their work. -

Choreography and Sounding Wearables

Scene 2 (1+2) pp. 197–220 Intellect Limited 2014 Scene Volume 2 numbers 1 & 2 © 2014 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/scene.2.1-2.197_1 Michèle danjoux London college of Fashion choreography and sounding wearables abstract Keywords This article explores the role of ‘sounding costumes’ and body-worn technologies for costume choreographic composition, with real-time interactional elements (such as microphones, body speakers, sensors) potentially integrated into movement and expressive behaviour. movement Sounding garments explore the interactions between dancer/performer, the costume and choreography the environment in the generation and manipulation of sonic textures. Briefly discussing sound historical precedents of integrated composition, the article will mainly refer to sounding wearable prototypes in DAP-Lab’s latest production, For the time being [Victory over the Sun] interactive (2012–2014), for which I designed the wearables, highlighting new methods for build- performance ing sensual wearable electro-acoustic costumes to create kinaesonic choreographies. The article analyses the multi-perspectival potentials of such conceptual garments/wear- able artefacts to play a significant part in the creation process of a performance, focus- ing on how wearable design can influence and shape movement vocabularies through the impact of its physical material presence on the body, distinctive design aesthetics and sound-generating capabilities. Choreographically, garments and body-worn tech- nologies act as amplifying instruments -

Costume Design: Key Questions

Costume Design: Key Questions Costume designer and architect Gabriela Yiaxis worked with Whitechapel Gallery Children's Commission 2015 artist Rivane Neuenschwander on the exhibition The Name of Fear. Gabriela is an experienced freelance costume designer who works worldwide on feature films, advertisements, TV, fashion and music. In this resource she shares key questions and the process of taking a costume from script to screen. Rivane Neuenschwander: The Name of Fear 2015 Costume Design: Key Questions Costume designer Gabriela Yiaxis shares some of her key considerations when developing costumes for feature films. Think about how all of these questions effect what you see on screen, some of these questions can also be applied to developing costume for theatre, advertising campaigns and catwalk collections. Setting What is the story about? Is the film contemporary, futuristic, epic, period? Which exactly era? Does the storyline have a fantasy or realistic approach? How does the director wants to tell the story? Funny, realistic, surreal? Will the film be shot in black and white, sepia, colour? Who is the audience for the finished product? Costume Design: Key Questions Building a character Examples of questions you should ask yourself when they are not on a script . How old are they? Is the character rich or poor? What is their social status? Aristocracy, working class, middle class? What is the characters family background? Are they from a traditional family background, alternative family background, single parent household, grew up in care? What is the characters role in the story? Banker, waitress, doctor, athlete, writer, homeless, musician, salesman, criminal? Consider how the characters personality affects the costume. -

Video Games and Costume Art -Digitalizing Analogue Methods of Costume Design

Video Games and Costume Art -digitalizing analogue methods of costume design Heli Salomaa MA thesis 30 credits Department of Film, Television and Scenography Master’s Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television Major in Costume Design Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture Supervisor: Sofia Pantouvaki Advisors: Petri Lankoski, Maarit Kalmakurki 2018 Aalto University, P.O. BOX 11000, 00076 AALTO www.aalto.fi Master of Arts thesis abstract ! Author Heli Salomaa Title of thesis Video Games and Costume Art - digitalizing analogue methods of costume design Department Department of Film, Television and Scenography Year 2018 Number of pages 100 Language English Degree programme Master's Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television, Major in Costume Design Abstract This thesis explores ways of integrating a costume professional to the character art team in the game industry. The research suggests, that integrating costume knowledge into the character design pipeline increases the storytelling value of the characters and provides tools for the narrative. The exploration of integrating a costume professional into game character creation as a process is still rare and little information of costume in games and experiences in transferring an analogue character building skillset into a digital one can be found, therefore this research was generated to provide knowledge on the subject. The research's main emphasis is on immersion-driven AAA-games that employ 3D-graphics and human characters and are either photorealistic or represent stylized realism. Technology for depicting reality is advancing and digital industries have become aware of the extensive skills required to depict increasingly realistic worlds.