Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia and Thrombocytopenia in Clonal B-Cell Disorders: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simultaneous Pure Red Cell Aplasia and Auto-Immune Hemolytic Anemia in a Previously Healthy Infant

Simultaneous Pure Red Cell Aplasia and Auto-immune Hemolytic Anemia in a Previously Healthy Infant Robert P. Sanders, MD July 16, 2002 Case Presentation Patient Z.H. • Previously Healthy 7 month old WM • Presented to local ER 6/30 with 1 wk of decreased activity and appetite, low grade temp, 2 day h/o pallor. • Noted to have severe anemia, transferred to LeBonheur • Review of Systems – ? Single episode of dark urine – 4 yo sister diagnosed with Fifth disease 1 wk prior to onset of symptoms, cousin later also diagnosed with Fifth disease – Otherwise negative ROS •PMH – Term, no complications – Normal Newborn Screen – Hospitalized 12/01 with RSV • Medications - None • Allergies - NKDA • FH - Both parents have Hepatitis C (pt negative) • SH - Lives with Mom, 4 yo sister • Development Normal Physical Exam • 37.2 167 33 84/19 9.3kg • Gen - Alert, pale, sl yellow skin tone, NAD •HEENT -No scleral icterus • CHEST - Clear • CV - RRR, II/VI SEM at LLSB • ABD - Soft, BS+, no HSM • SKIN - No Rash • NEURO - No Focal Deficits Labs •CBC – WBC 20,400 • 58% PMN 37% Lymph 4% Mono 1 % Eo – Hgb 3.4 • MCV 75 MCHC 38.0 MCH 28.4 – Platelets 409,000 • Retic 0.5% • Smear - Sl anisocytosis, Sl hypochromia, Mod microcytes, Sl toxic granulation • G6PD Assay 16.6 U/g Hb (nl 4.6-13.5) • DAT, Broad Spectrum Positive – IgG negative – C3b, C3d weakly positive • Chemistries – Total Bili 2.0 – Uric Acid 4.8 –LDH 949 • Urinalysis Negative, Urobilinogen 0.2 • Blood and Urine cultures negative What is your differential diagnosis? Differential Diagnosis • Transient Erythroblastopenia of Childhood • Diamond-Blackfan syndrome • Underlying red cell disorder with Parvovirus induced Transient Aplastic Crisis • Immunohemolytic anemia with reticulocytopenia Hospital Course • Admitted to ICU for observation, transferred to floor 7/1. -

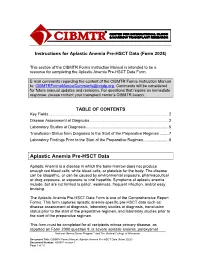

Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data (Form 2028)

Instructions for Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data (Form 2028) This section of the CIBMTR Forms Instruction Manual is intended to be a resource for completing the Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data Form. E-mail comments regarding the content of the CIBMTR Forms Instruction Manual to: [email protected]. Comments will be considered for future manual updates and revisions. For questions that require an immediate response, please contact your transplant center’s CIBMTR liaison. TABLE OF CONTENTS Key Fields ............................................................................................................. 2 Disease Assessment at Diagnosis ........................................................................ 2 Laboratory Studies at Diagnosis ........................................................................... 5 Transfusion Status from Diagnosis to the Start of the Preparative Regimen ........ 7 Laboratory Findings Prior to the Start of the Preparative Regimen ....................... 8 Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data Aplastic Anemia is a disease in which the bone marrow does not produce enough red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets for the body. The disease can be idiopathic, or can be caused by environmental exposure, pharmaceutical or drug exposure, or exposure to viral hepatitis. Symptoms of aplastic anemia include, but are not limited to pallor, weakness, frequent infection, and/or easy bruising. The Aplastic Anemia Pre-HSCT Data Form is one of the Comprehensive Report Forms. This form captures aplastic -

An Incidental Case of Transient Erythroblastopenia of Childhood

Clinical Pediatrics: Open Access Case Report An Incidental Case of Transient Erythroblastopenia of Childhood Allen Mao1*, Brian Gavan2, Curtis Turner3 1University of South Alabama, College of Medicine, Mobile, Alabama, USA;2Department of Pediatrics, University of South Alabama Children’s and Women’s Hospital, Mobile, Alabama, USA;3Department of Pediatrics, University of South Alabama Children’s and Women’s Hospital, Mobile, Alabama, USA ABSTRACT We highlight a pediatric case of Transient Erythroblastopenia of Childhood (TEC) and compare with published reports and contrast TEC with other causes of anemia, most notably Diamond Blackfan Anemia (DBA). Secondly, many of the business. The development of anemia may be subtle, and TEC is a diagnosis of exclusion. The broad differential diagnoses of anemia include decreased RBC production (erythropoiesis) or increased RBC destruction (hemolytic anemias). Decreased RBC production includes viral suppression and bone marrow failure (congenital or acquired). Keywords: Hepatosplenomegaly; Anemia; Erythroblastopenia; Echovirus INTRODUCTION CASE PRESENTATION Transient Erythroblastopenia of Childhood (TEC) is Our patient was a healthy 12 month old African American male characterized by a temporary cessation of erythrocyte production with no significant past medical history who presented for a well- with continued production of white blood cells and platelets in child checkup. Screening CBC and lead level were obtained. His previously healthy children. This is the most common Pediatric vital signs were temperature 36.6°C, pulse 136, and respiratory Pure Red Cell Aplasia (PRCA), an isolated anemia with rate 28. The physical exam was significant for mild conjunctival reticulocytopenia [1]. The etiology is unknown, yet suspected pallor, his height was in the 89th percentile, weight in 42nd causes of Transient Erythroblastopenia of Childhood (TEC) percentile, and he had no abnormal facies, digit abnormalities, include preceding viral illnesses (e.g. -

Blood Toxicity Lab 7

6/22/2020 Blood toxicity lab 7 Blood Basics Blood is a specialized body fluid. It has four main components: plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Blood has many different functions, including: 1-Transporting oxygen and nutrients to the lungs and tissues 2-Forming blood clots to prevent excess blood loss 3-Carrying cells and antibodies that fight infection 4-Bringing waste products to the kidneys and liver, which filter and clean the blood 5-Regulating body temperature 1 6/22/2020 Hematology: is the science or study of blood, blood-forming organs and blood diseases. In the medical field, hematology includes the treatment of blood disorders and malignancies, including types of hemophilia, leukemia, lymphoma and sickle-cell anemia. Hematotoxicology : is the study of adverse effects of drugs, nontherapeutic chemicals, and other chemicals in our environment on blood and blood-forming tissues. Each of the various blood cells (erythrocytes, granulocytes, and platelets) is produced at a rate of approximately one to three million/s in a healthy adult and several times that rate in conditions where demand for these cells is high, as in hemolytic anemia or suppurative inflammation. The hematopoietic tissue is also susceptible to : 1-The secondary effects of toxic agents that affect the supply of nutrients, such as iron 2- The clearance of toxins and metabolites, such as urea 3- The production of vital growth factors, such as erythropoietin and granulocyte colony- stimulating factor(G-CSF). 2 6/22/2020 The consequences of direct or indirect damage to blood cells and their precursors are predictable and potentially life-threatening. -

Epoietin-Induced Antibody-Mediated Pure Red Cell Aplasia and Responses to Immunosuppression Therapy: 2 Case Reports and Literature Review

內科學誌 2010:21:441-447 Epoietin-induced Antibody-mediated Pure Red Cell Aplasia and Responses to Immunosuppression Therapy: 2 Case Reports and Literature Review Yuan-Hsin Chang1,3, Ken-Hong Lim1, Hsin-Chang Lin2, Ming-Chih Chang1, Gon-Shen Chen1, Ruey-Kuen Hsieh1 1Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei 10449, Taiwan; 2Department of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei 10449, Taiwan; 3Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Sijhih Cathay General hospital, Taipei County 22174 Abstract Recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) induced antibody-mediated pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) was a rare disease. Herein, we reported 2 cases with confirmed diagnosis of EPO- induced antibody- mediated PRCA in our institution. Case 1: a 53 year-old female with uremia and regular hemodialysis was regularly administered with EPO-α (Eprex) subcutaneously. Progressive unexplained anemia was noted 13 months after therapy with Eprex. Bone marrow study revealed remarkable erythroid hypoplasia compatible with PRCA. Anti-EPO antibody levels were detected. After withdrawal of Eprex and administration of cyclo- sporine, her anemia gradually improved. Serum level of anti-EPO antibody became undetectable. Another form of EPO (darbepoetin) was administered to the patient and hemoglobin recovered to 10.4 g/dL. Case 2: a 46 year-old male with chronic kidney disease related anemia underwent a regular subcutaneous EPO-β (Recormon) therapy. He developed profound anemia in spite of dose increase of EPO-β and combination with darbepoetin usage. EPO induced antibody-mediated PRCA was confirmed by the detection of anti-EPO antibody and severe erythroid hypoplasia in the bone marrow. -

Immune-Mediated Pure Red Cell Aplasia in Renal Transplant Recipients

Letters to the Editor Amsterdam) for their collaboration in the MLPA kit development. majority of cases,1 the diagnosis of immune-mediated Key words: Diamond-Blackfan anemia, RPS19, deletion, MLPA. cytopenia is rarely considered in organ transplant recipi- Corresponcence: Ugo Ramenghi, MD, Associate Professor of ents, given the immunocompromised status. Etiologies of Pediatrics, Hematology Unit, Pediatric Department, University of post-transplant PRCA are rather dominated by chronic Torino, Piazza Polonia 94, 10126, Torino, Italy. Phone: internation- parvovirus B19 infections2 and drug-induced bone mar- al +39.011.3135788. Fax: international +39.011.3135382. 3 E-mail: [email protected] row toxicity. However, in most cases reported in the lit- Citation: Quarello P, Garelli E, Brusco A, Carando A, Pappi P, erature with drug-induced PRCA, cyclosporine A (CyA) Barberis M, Coletti V, Campagnoli MF, Dianzani I, and was introduced to replace the incriminated drug. We, Ramenghi U. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification therefore, hypothesized that some post-transplant PRCA (MLPA) enhances molecular diagnosis of Diamond-Blackfan may be immune-mediated, especially in renal transplant anemia due to RPS19 deficiency. Haematologica 2008; 93:1748- 1750. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13423 recipients treated with a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-free regimen. This hypothesis is supported by an unexpected- ly high frequency of LGL-like clonal disorders in organ References transplant recipients,4 and by a recent report of autoim- mune cytopenia occurring in up to 5.6% of pancreas 1. Campagnoli MF, Garelli E, Quarello P, Carando A, Varotto transplant recipients receiving a calcineurin inhibitor-free S, Nobili B, et al. Molecular basis of Diamond-Blackfan 5 anemia: new findings from the Italian registry and a regimen. -

Acoi Board Review 2017 Text

CHERYL KOVALSKI, DO FACOI NO DISCLOSURES ACOI BOARD REVIEW 2017 TEXT ANEMIA ‣ Hemoglobin <13 grams or ‣ Hematocrit<39% TEXT IRON DEFICIENCY ‣ Most common nutritional problem in the world ‣ Absorbed in small bowel, enhanced by gastric acid ‣ Absorption inhibited by inflammation, phytates (bran) & tannins (tea) TEXT CAUSES OF IRON DEFICIENCY ‣ Blood loss – most common etiology ‣ Decreased intake ‣ Increased utilization-EPO therapy, chronic hemolysis ‣ Malabsorption – gastrectomy, sprue ‣ ‣ ‣ TEXT CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF IRON DEFICIENCY ‣ Impaired psychomotor development ‣ Fatigue, Irritability ‣ PICA ‣ Koilonychiae, Glossitis, Angular stomatitis ‣ Dysphagia TEXT ANEMIA MCV RETICULOCYTE COUNT Corrected retic ct : >2%: blood loss or hemolysis <2%: hypoproliferative process TEXT ANEMIA ‣ MICROCYTIC ‣ Obtain and interpret iron studies ‣ Serum iron ‣ Total iron binding capacity (TIBC) ‣ Transferrin saturation ‣ Ferritin-correlates with total iron stores ‣ can be nml or inc if co-existent inflammation TEXT IRON DEFICIENCY LAB FINDINGS ‣ Low serum iron, increased TIBC ‣ % sat <20 TEXT MANAGEMENT OF IRON DEFICIENCY ‣ MUST LOOK FOR SOURCE OF BLEED: ie: GI, GU, Regular blood donor ‣ Replacement: 1. Oral: Ferrous sulfate 325 mg TID until serum iron, % sat, and ferritin mid-range normal, 6-12 months 2. IV TEXT SIDEROBLASTIC ANEMIAS Diverse group of disorders of RBC production characterized by: 1. Defect involving incorporation of iron into heme molecule 2. Ringed sideroblasts in bone marrow javascript:refimgshow(1) TEXT CLASSIFICATION OF SIDEROBLASTIC -

Successful Treatment of Pure Red Cell Aplasia of an 88-Year-Old Case With

haematologica online 2004 8-36 mU/mL). Examination of the patient’s bone mar- Successful treatment of pure red cell aplasia of row showed severe hypoplasia specific for erythroid an 88-year-old case with cyclosporin A and ery- lines (erythroid, 0%) but leukemic blasts and no abnor- thropoietin after thymectomy mality in other cell lineages, suggesting a diagnosis of pure red cell aplasia. Antinuclear antibody titer was ×640 An 88-year-old Japanese female with pure red (homogeneous and speckled pattern). The HLA-DRB1 cell aplasia was treated safely and effectively by a alleles included 0101 and 0405. Chest roentgenogram combination of thymectomy, cyclosporin A, and revealed an enlarged heart with a cardiothoracic ratio of erythropoietin. The thymoma was histologically 54% and the presence of pleural effusion, suggesting classified as lymphocytic type or cortical type, impaired cardiac function by severe anemia. which are uncommon in cases of a thymoma Computerized chest tomography revealed a relatively accompanied by pure red cell aplasia. large thymic mass (3×3 cm) for her advanced age. Immunohistochemical analysis of the thymoma Although all previous medication prior to the admission and bone marrow revealed a predominance of was withdrawn, anemia was not improved. In order to CD8+ cells. Thymectomy alone was ineffective, but suppress the suspected autoimmune condition, a cyclosporin A treatment subsequent to thymecto- thymectomy was performed. The pathological diagnosis my was safe and effective and resulted in the dis- of the thymic mass was thymoma of lymphocytic type appearance of a Vβ12 bearing T cell clone in the (the Lattes-Bernatz classification) or cortical type (the bone marrow. -

ICD-10 Guide for Common Non-Malignant Blood Disorders

ICD-10 Guide for Common Non-Malignant Blood Disorders Hemolytic Anemias Sickle Cell Disorders Aplastic Anemias and Other Bone D55.0 Anemia due to G6PD deficiency Marrow Failures D57.00 Hb-SS disease w/ crisis, unspecified D55.1 Anemia due to other disorders of D60.0 Chronic acquired pure red cell aplasia D57.01 Hb-SS disease w/ acute chest glutathione metabolism D60.1 Transient acquired pure red cell syndrome D55.2 Anemia due to disorders of glycolytic aplasia D57.02 Hb-SS disease w/ splenic enzymes D60.8 Other acquired pure red cell aplasias sequestration D55.3 Anemia due to disorders of nucleotide D60.9 Acquired pure red cell aplasia, D57.1 Sickle cell disease w/o crisis metabolism unspecified D57.20 Sickle cell/Hb-C disease w/o crisis D55.8 Other anemias due to enzyme disorders D61.01 Constitutional (pure) red blood cell D57.21 Sickle cell/Hb-C disease w/ crisis D55.9 Anemia due to enzyme disorder, aplasia D57.211 Sickle cell/Hb-C disease w/ acute unspecified D61.09 Other constitutional aplastic anemia chest syndrome D61.1 Drug-induced aplastic anemia D57.212 Sickle cell/Hb-C disease w/ splenic Thalassemia D61.2 Aplastic anemia due to other external sequestration agents D56.0 Alpha thalassemia D57.219 Sickle cell/Hb-C disease w/ crisis, D61.3 Idiopathic aplastic anemia D56.1 Beta thalassemia unspecified D61.810 Antineoplastic chemotherapy induced D56.2 Delta-beta thalassemia D57.3 Sickle cell trait pancytopenia D56.3 Thalassemia minor D57.40 Sickle cell thalassemia w/o crisis D61.811 Other drug-induced pancytopenia D56.4 Hereditary -

PNH) with Complex Evolution and Liver Transplant Jornal Brasileiro De Patologia E Medicina Laboratorial, Vol

Jornal Brasileiro de Patologia e Medicina Laboratorial ISSN: 1676-2444 [email protected] Sociedade Brasileira de Patologia Clínica/Medicina Laboratorial Brasil Alencar, Railene Célia B.; Guimarães, Andréa M.; Brito Junior, Lacy C. Report of a case of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) with complex evolution and liver transplant Jornal Brasileiro de Patologia e Medicina Laboratorial, vol. 52, núm. 5, octubre, 2016, pp. 307-311 Sociedade Brasileira de Patologia Clínica/Medicina Laboratorial Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=393548491005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative CASE REPORT J Bras Patol Med Lab, v. 52, n. 5, p. 307-311, October 2016 Report of a case of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) with complex evolution and liver transplant 10.5935/1676-2444.20160051 Relato de um caso de hemoglobinúria paroxística noturna (HPN) com evolução complexa e transplante hepático Railene Célia B. Alencar; Andréa M. Guimarães; Lacy C. Brito Junior Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), Pará, Brazil. ABSTRACT The paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare acquired disease, with thrombotic episodes and frequent pancytopenia. We report the case of a 32 year-old female PNH patient with bone marrow aplasia, which followed a complex course, diagnosed with aplastic anemia associated with PNH, evolving in three years with Budd-Chiari syndrome and liver transplantation. Post-transplant complications, hepatic arterial thrombosis, graft rejection, liver retransplantation and treatment of PNH with eculizumab. -

Anti-Erythropoietin Antibodies and Pure Red Cell Aplasia

DISEASE OF THE MONTH J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 398–406, 2004 EBERHARD RITZ, FEATURE EDITOR Anti-Erythropoietin Antibodies and Pure Red Cell Aplasia JEROME ROSSERT,* NICOLE CASADEVALL,† AND KAI-UWE ECKARDT,‡ *Department of Nephrology, Tenon hospital (AP-HP) and Pierre and Marie Curie University, Paris, France; †Department of Hematology, Hôtel Dieu (AP-HP), Paris, France; and ‡Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Charité, Campus Virchow Klinikum, Berlin, Germany More than twenty years ago, investigators who immunized unrecognized phenomenon have not been confirmed, and the rabbits against human erythropoietin (EPO) to generate poly- incidence rates of epoetin-induced PRCA seem to have passed clonal antibodies noted that the animals producing antibodies the peak. Nevertheless, clinicians should be aware of signs and against this hormone became progressively anemic (1). Appar- consequences of this complication. Moreover, this issue raises ently human EPO was sufficiently different from rabbit EPO to important safety considerations for the development and ap- be recognized as a foreign protein; however the antibodies proval of future epoetin molecules and biogenerics, in general. were crossreactive with rabbit EPO and neutralized it. At that time the anemia observed in these animals provided indirect Pure Red Cell Aplasia: A Rare Hematological Disease proof that EPO is an essential growth factor for erythropoiesis. PRCA is an isolated disorder of erythropoiesis that leads to Patients have been treated with recombinant human EPO a progressive, severe anemia of sudden onset (11). Due to an (rHuEPO or epoetin) since the late 1980s. Initially, the recom- almost complete cessation of red blood cell (RBC) production 3 binant hormone was only given intravenously. -

Could Anti-Erythropoietin Receptor Antibodies Be the Future Management of Beta Thalassemia Intermedia?

Elmer ress Letter to the Editor J Hematol. 2016;5(4):151-153 Could Anti-Erythropoietin Receptor Antibodies Be the Future Management of Beta Thalassemia Intermedia? Ashraf Abdullah Saad To the Editor the chronic anemic state results in erythropoietin production become unchecked [6]. Erythropoietin drives the proliferation of erythroid precursors in the bone marrow and extramedullary Thalassemia syndromes are the most common hereditary sites. Erythroid marrow hypertrophy can reach up to 25 - 30 genetic diseases of mankind. They result from an imbalance times the normal marrow cavity volume and leads to the char- between the number of alpha-and beta-globin chains. When acteristic skeletal deformities, osteoporosis and pathological the amount of beta-globin chains are absent or reduced, the fractures of long bones [7]. More interestingly is the extramed- disease is called beta thalassemia. However, the pathology is ullary expansion. This results from the arrest at differentiation entirely related to the relative excess of alpha-globin chains. of erythroid precursors in response to sustained erythropoietin These highly unstable chains precipitate within erythroid pre- surge leading to sustained proliferation of the erythropoietic cursors in the bone marrow causing direct membrane damage tissue that sweep past the bone marrow to invade and colonize and premature cell death by apoptosis. This central hemolysis all body sites but predominantly homing the spleen and liver. is termed as ‘ineffective erythropoiesis’ and is the main deter- This is termed ‘extramedullay hematopoiesis’ (EMH) which minant of anemia in beta thalassemia [1]. Peripheral hemoly- can result in devastating complications as these masses can sis of mature red blood cells is caused by this mechanism but grow up in tumor-like forms.