The Relevance of Persistence Hunting to Human Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Marathon Running: Capabilities in Humans

The Evolution of Marathon Running: Capabilities in Humans The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lieberman, Daniel E., and Dennis M. Bramble. 2007. The evolution of marathon running: Capabilities in humans. Sports Medicine 37(4-5): 288-290. Published Version doi:10.2165/00007256-200737040-00004 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3716644 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Sports Med 2007; 37 (4.6): 288-290 CONFERENCE PAPER 0112-1642/07/0004<l2a8/S44.'J5/0 e 2007 Adis Data Intormatian BV. All rights reserved. The Evolution of Marathon Running Capabilities in Humans Daniel E. Lieberman^ and Dennis M. Bramble^ 1 Departments of Anthropology and Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA 2 Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA AbStrOCt Humans have exceptional capabilities to run long distances in hot, arid conditions. These abilities, unique among primates and rare among mammals, derive from a suite of specialised features that permit running humans to store and release energy effectively in the lower limb, help keep the body's center of mass stable and overcome the thermoregulatory challenges of long distance running. Human endurance running perfonnance capabilities compare favourably with those of other mammals and probably emerged sometime around 2 million years ago in order to help meat-eating hominids compete with other carnivores. -

Lack of Water and Endurance Running Could Have Caused the Exponential Growth in Human Brain “Point of No Return” Model

Lack of water and endurance running could have caused the exponential growth in human brain “Point of no return” model Konrad R. Fialkowski University of Warsaw, Poland; An den Langen Luessen 9/1/3; 1190 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: [email protected] Growth in brain volume is one of the most spectacular changes in the hominid lineage. The anthropological community agrees on that point. No consensus, however, has been reached on selection pressures contributing to that growth. In that respect Martin (1984) can be invoked. In his review of size relationships among primates he stated that despite the relationship between brain size, body size and feeding behavior no single interpretation could be provided that revealed the causality of such relationship. This paper deals with one specific aspect of hominid brain growth: the fact that for most of the hominid period, growth in brain volume was exponential in character. To the author’s knowledge, no attempt has been made to identify a selection mechanism that can facilitate just the exponential features of that growth (as distinct from any of its other characteristics). It is broadly accepted that the dynamics of this growth were peculiar. Growth was very fast, or even rapid in the evolutionary scale of time. The most profound evidence of that opinion was expressed by Haldane (quoted after Mayr 1970: 384): “J. B. S. Haldane liked to emphasize that this dramatic increase in brain size was the most rapid evolutionary change known to him”. EXPONENTIAL GROWTH OF HOMINID BRAIN VOLUME In mathematical terms the exponential function is the very fast growing function. -

An Anthropological Assessment of Neanderthal Behavioural Energetics

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY, CLASSICS & EGYPTOLOGY An Anthropological Assessment of Neanderthal Behavioural Energetics. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Andrew Shuttleworth. April, 2013. TABLE OF CONTENTS……………………………………………………………………..i LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………………v LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………………………..vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………………...vii ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………………viii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................1 1.1. Introduction..............................................................................................................1 1.2. Aims and Objectives................................................................................................2 1.3. Thesis Format...........................................................................................................3 2. THE NEANDERTHAL AND OXYEGN ISOTOPE STAGE-3.................................6 2.1. Discovery, Geographic Range & Origins..............................................................7 2.1.1. Discovery........................................................................................................7 2.1.2. Neanderthal Chronology................................................................................10 2.2. Morphology.............................................................................................................11 -

The Relevance of Persistence Hunting to Human Evolution

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Journal of Human Evolution 55 (2008) 1156–1159 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol News and Views The relevance of persistence hunting to human evolution Louis Liebenberg Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, 11 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA article info of ER in early Homo. In addition, sophisticated PH may have contributed to the evolution of modern human intellectual abilities. Article history: Received 9 February 2008 Accepted 7 July 2008 Context of recent observations Keywords: The statement that ‘‘over the course of 20 years, only two of the Endurance running Foragers ER hunts observed by Liebenberg were spontaneous’’ (Pickering Homo and Bunn, 2007: 436) is misleading. Firstly, I should clarify the Hunter-gatherers context within which I conducted my field research over the course Persistence hunting of 20 years. As an independent researcher (with no funding), I Tracking would have liked to have witnessed more hunts, but I simply did not have the financial means to do so. -

Language Evolution to Revolution

Research Ideas and Outcomes 5: e38546 doi: 10.3897/rio.5.e38546 Research Article Language evolution to revolution: the leap from rich-vocabulary non-recursive communication system to recursive language 70,000 years ago was associated with acquisition of a novel component of imagination, called Prefrontal Synthesis, enabled by a mutation that slowed down the prefrontal cortex maturation simultaneously in two or more children – the Romulus and Remus hypothesis Andrey Vyshedskiy ‡ ‡ Boston University, Boston, United States of America Corresponding author: Andrey Vyshedskiy ([email protected]) Reviewable v1 Received: 25 Jul 2019 | Published: 29 Jul 2019 Citation: Vyshedskiy A (2019) Language evolution to revolution: the leap from rich-vocabulary non-recursive communication system to recursive language 70,000 years ago was associated with acquisition of a novel component of imagination, called Prefrontal Synthesis, enabled by a mutation that slowed down the prefrontal cortex maturation simultaneously in two or more children – the Romulus and Remus hypothesis. Research Ideas and Outcomes 5: e38546. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.5.e38546 Abstract There is an overwhelming archeological and genetic evidence that modern speech apparatus was acquired by hominins by 600,000 years ago. On the other hand, artifacts signifying modern imagination, such as (1) composite figurative arts, (2) bone needles with an eye, (3) construction of dwellings, and (4) elaborate burials arose not earlier than © Vyshedskiy A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Run for Your Life Humans Evolved to Run

COMMENT ILLUSTRATION BY PHIL DISLEY BY ILLUSTRATION Run for your life Humans evolved to run. This helps to explain our athletic capacity and our susceptibility to modern diseases, argue Timothy Noakes and Michael Spedding. he forthcoming Olympics in London Charlie, holds the English marathon record regularly to chase down meat. For many, will celebrate the performance capac- and won Olympic bronze in 1984 by ignor- exercise is no longer an integral part of daily ity of humans and our remarkable ing drink stations at crucial stages in the Los life, leading to a host of modern ailments. Tability to prepare our bodies and minds for Angeles marathon. We began exchanging In short, we think specific tasks. But, at the same time as we e-mails. Eventually, that correspondence “Most humans that exercise is not just are pushing our bodies to new limits in ath- coalesced into the theory we outline here. today do not important for general leticism, we are experiencing unprecedented Over millions of years, humans evolved live in an health — it is essen- levels of relatively modern diseases such as from tree-dwelling apes to become Homo environment tial to the molecular obesity, diabetes and psychiatric and neuro- sapiens, capable of elite athleticism1. Simply where they memory of who we degenerative disorders. put, we evolved to run. While early homi- must chase are. Without it, we are We, the authors, were both considering nins were undergoing intense skeletal and down meat.” at risk of being obese the modern paradox of elite athleticism and metabolic changes, major changes also and diabetic, and of growing susceptibility to disease when we occurred in their brains2. -

The Endurance Running Hypothesis and Hunting and Scavenging in Savanna-Woodlands

Journal of Human Evolution 53 (2007) 434e438 News and Views The endurance running hypothesis and hunting and scavenging in savanna-woodlands Travis Rayne Pickering a,b,*, Henry T. Bunn a a Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, 5240 Social Science Building, Madison, Wisconsin 57306, USA b Institute for Human Evolution, University of the Witwatersrand, WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa Received 15 June 2006; accepted 3 January 2007 Keywords: Carcass foraging; Early Homo; Tracking; Zooarchaeology Introduction However, as with any provocative idea, there are several as- pects of the ER hypothesis pertaining to carcass acquisition Recently, Bramble and Lieberman (2004: 345) provided that warrant deeper examination. We believe that even within a review of morphological evidence suggesting to them the ‘‘limitations of the archaeological and ethnographic re- ‘‘that endurance running is a derived capability of the genus cords’’ there are data available to test the hypothesis that hunt- Homo, originating about 2 million years [Myr] ago, and may ing and scavenging selected for ER in early Homo. Here, we have been instrumental in the evolution of the human body focus on paleohabitat and paleoecology as factors that, when form.’’ The authors went on to hypothesize that long-distance considered in combination with the realities of pursuit- endurance running (ER) may have been critical to encephal- foraging, diminish the plausibility of early Homo using ER ized early Homo in gaining access to high-quality food re- in hunting and scavenging. sources, including especially meat, marrow, and brains. They The ca. 2.3e1.5-Myr-old African environments of H. -

4-Bunn-Gurtov-Hunting.Pdf

Quaternary International 322-323 (2014) 44e53 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Prey mortality profiles indicate that Early Pleistocene Homo at Olduvai was an ambush predator Henry T. Bunn*, Alia N. Gurtov University of WisconsineMadison, Department of Anthropology, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706, United States article info abstract Article history: The prime-adult-dominated mortality profile of large bovids in the 1.8 Ma FLK Zinj assemblage, Olduvai Available online 23 November 2013 Gorge, Tanzania, was recently attributed to ambush hunting by early Homo (Bunn, H.T., Pickering, T.R. 2010. Quat. Res. 74, 395e404). We now investigate a logical follow-up question: is enough known about the causes and pervasiveness of prime-adult-dominated mortality profiles (defined as >70% prime adults) from modern ecosystems and from archaeological sites to warrant their attribution solely to hominin hunting? Besides hominin hunting, three methods of scavenging could have provided the large bovids butchered at FLK Zinj: first-access scavenging from non-predator-related accidents; late-access passive scavenging from lion (or other) kills; early-access aggressive scavenging from lion (or other) kills. We present new data on hunted prey from Hadza bow hunting (e.g., N ¼ 50 impala; N ¼ 18 greater kudu) near Lake Eyasi, Tanzania, and from San bow hunting (N ¼ 13 gemsbok) in the Kalahari Desert, Botswana, documenting non-selective, living-structure profiles. We present new data on drowned wildebeest (N ¼ 175) from Lake Masek, in the Serengeti, documenting many prime adults but also a significantly high percentage of old adults, unlike the profile at FLK Zinj. -

Bovid Mortality Profiles in Paleoecological Context Falsify

Quaternary Research 74 (2010) 395–404 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yqres Bovid mortality profiles in paleoecological context falsify hypotheses of endurance running–hunting and passive scavenging by early Pleistocene hominins Henry T. Bunn a,⁎, Travis Rayne Pickering a,b a Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, 5240 Social Science Building, Madison, Wisconsin, 53706, USA b Institute for Human Evolution, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa article info abstract Article history: The world’s first archaeological traces from 2.6 million years ago (Ma) at Gona, in Ethiopia, include sharp- Received 21 February 2010 edged cutting tools and cut-marked animal bones, which indicate consumption of skeletal muscle by early hominin butchers. From that point, evidence of hominin meat-eating becomes increasingly more common Keywords: throughout the Pleistocene archaeological record. Thus, the substantive debate about hominin meat-eating Uniformitarianism now centers on mode(s) of carcass resource acquisition. Two prominent hypotheses suggest, alternatively, Bovid mortality profiles (1) that early Homo hunted ungulate prey by running them to physiological failure and then dispatching Carcass foraging Early Homo them, or (2) that early Homo was relegated to passively scavenging carcass residues abandoned by carnivore FLK 22 Zinjanthropus predators. Various paleontologically testable predictions can be formulated for both hypotheses. Here we test four predictions concerning age-frequency distributions for bovids that contributed carcass remains to the 1.8 Ma. old FLK 22 Zinjanthropus (FLK Zinj, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania) fauna, which zooarchaeological and taphonomic data indicate was formed predominantly by early Homo. -

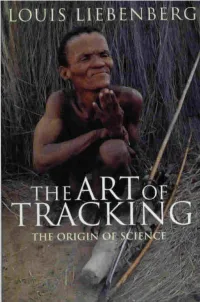

The Art of Tracking the Origin of Science

The Art of Tracking Tbe Origin of Science Louis Liebenberg David Philip First published 1990 in southern Africa by David Philip Publishers (Pty) Ltd 208 Werdmuller Centre, Claremont 7700, South Africa text © Louis Liebenherg illustrations © Louis Liebenherg All rights reserved ISBN 0 R6486 131 1 Typesetting hy Desktop Design cc, Shortmarket Street. Cape Town Printed hy Creda Press. Solan Road. Cape Town Contents Introduction . v Part I: The Evolution of Hunter-Gatherer Subsistence 1 1 Hominid Evolution . 3 2 The Evolution of Hominid Subsistence 11 3 The Evolution of Tracking . 29 4 The Origin of Science ,tnd Art 41 Part U: Hunter-Gatherers of the Kalahari ....... -l9 S Hunter-Gatherer Subsi�tence . 51 6 Scientific Knowledge of Spoor and Animal Behaviour 69 .... Non-scientific Aspects of Hunting . 93 Part lli: The Fundamentals of Tracking . 99 8 Principles of Tr.tcking 101 9 Classification of Signs 111 10 Spoor Interpretation 121 11 Scientific Research Programmes 153 References 167 Index . 173 Introduction According to a popular misconception, nature is "like an open book" to the expert tracker and such an expert needs only enough skill to "read everything that is written in the sand". A more appropriate analogy would be that the expert tracker must be able to "read between the lines". Trackers themselves cannot read everything in the sand. Rather, they must be able to read into the sand. To interpret tracks and signs trackers must project themselves into the position of the animal in order to create a hypothetical explanation of what the animal was doing. Tracking is not strictly empirical, since it also involves the tracker's imagination. -

Energy Cost and Return for Hunting in African Wild Dogs and Cheetahs

ARTICLE Received 24 Jul 2015 | Accepted 12 Feb 2016 | Published 29 Mar 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms11034 OPEN Energy cost and return for hunting in African wild dogs and cheetahs Tatjana Y. Hubel1, Julia P. Myatt1,2, Neil R. Jordan3,4,5, Oliver P. Dewhirst1, J. Weldon McNutt3 & Alan M. Wilson1 African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) are reported to hunt with energetically costly long chase distances. We used high-resolution GPS and inertial technology to record 1,119 high-speed chases of all members of a pack of six adult African wild dogs in northern Botswana. Dogs performed multiple short, high-speed, mostly unsuccessful chases to capture prey, while cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) undertook even shorter, higher-speed hunts. We used an energy balance model to show that the energy return from group hunting and feeding substantially outweighs the cost of multiple short chases, which indicates that African wild dogs are more energetically robust than previously believed. Comparison with cheetah illustrates the trade-off between sheer athleticism and high individual kill rate characteristic of cheetahs, and the energetic robustness of frequent opportunistic group hunting and feeding by African wild dogs. 1 Structure and Motion Laboratory, Royal Veterinary College, University of London, Hatfield AL97TA, UK. 2 School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK. 3 Botswana Predator Conservation Trust, Maun, Botswana. 4 Centre for Ecosystem Science, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2015, Australia. 5 Taronga Conservation Society Australia, Applied Eco-Logic Group, Taronga Western Plains Zoo, Dubbo, New South Wales 2830, Australia. -

To Run Or to Carry: Derived Traits in Early Members of the Genus Homo

To Run or to Carry: Derived Traits in Early Members of the Genus Homo Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Webber, James Thomas Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 13:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642005 TO RUN OR TO CARRY: DERIVED TRAITS IN EARLY MEMBERS OF THE GENUS HOMO By James T. Webber Copyright © James T. Webber 2020 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank the College of School of Behavioral and Social Sciences for the Dissertation Research Grant (award number: 18DRF0885), and the University of Arizona School of Anthropology for the Haury Dissertation Fellowship for supporting this dissertation research. I am thankful for my committee members, Dr. David Raichlen, Dr. Ivy Pike, Dr. Stacey Tecot, and Dr. Steven Kuhn who helped shape and inspire this research through their mentorship, conversations, personal research, and classes taught. I am especially grateful to my chair, Dr. David Raichlen who took a shot on a small-town undergrad interested in barefoot running, for his support, belief, mentorship, and positive outlook on the totality of the grad school experience.