CG Jung's Encounter with Kundalini and His Interpretation of Tantra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self Awakening

Self Awakening May 1, 2019 Maha Yoga – Effortless, joyful and no-cost path to Self-Realization Volume 11, Issue 4 EEditor’s note Dear Readers: The purpose of this quarterly newsletter, Self Awakening, is to inform Sadhaks (seekers of self-realization) and other readers about Maha Yoga, an effortless, joyful and no cost path to Self- Realization. P. P. Shri Narayan Kaka Maharaj of Nashik, India was a leading teacher and exponent of Maha Yoga, a centuries old tradition, Contents whereby a realized Guru (Siddha Guru) awakens the Universal Life Energy (Kundalini) within the Sadhak, eventually leading Editor’s note 1 him/her to self-realization. This ancient tradition (Parampara) Churning of the Heart 2 continues under the leadership of several Siddha Gurus, including the fourteen designated by P. P. Kaka Maharaj as Bringing Maha Yoga to the World 7 Deekshadhikaris (those authorized to initiate Sadhaks into Maha Shankaracharya discourse 10 Yoga). Additional details about Maha Yoga are available at Answers to questions 14 www.mahayoga.org. Book announcement 19 To the thousands of Sadhaks in the Maha Yoga tradition all over Upcoming events 20 the world and other interested readers, this e-newsletter is intended to provide virtual Satsang. It is intended to encourage Website updates 21 Sadhaks to remain engaged in Maha Yoga, be informed about How to contribute content 22 Maha Yoga-related events around the world, and to provide a forum for getting guidance about Maha Yoga from leaders from P. P. Shri Kaka Maharaj’s lineage. Readers are urged to contribute questions, thoughtful articles, interesting life experiences related to Maha Yoga and news about Maha Yoga-related events to this e-newsletter. -

Magicians, Sorcerers and Witches: Considering Pretantric, Non-Sectarian Sources of Tantric Practices

Article Magicians, Sorcerers and Witches: Considering Pretantric, Non-sectarian Sources of Tantric Practices Ronald M. Davidson Department of Religious Studies, Farifield University, Fairfield, CT 06824, USA; [email protected] Received: 27 June 2017; Accepted: 23 August 2017; Published: 13 September 2017 Abstract: Most models on the origins of tantrism have been either inattentive to or dismissive of non-literate, non-sectarian ritual systems. Groups of magicians, sorcerers or witches operated in India since before the advent of tantrism and continued to perform ritual, entertainment and curative functions down to the present. There is no evidence that they were tantric in any significant way, and it is not clear that they were concerned with any of the liberation ideologies that are a hallmark of the sectarian systems, even while they had their own separate identities and specific divinities. This paper provides evidence for the durability of these systems and their continuation as sources for some of the ritual and nomenclature of the sectarian tantric traditions, including the predisposition to ritual creativity and bricolage. Keywords: tantra; mantra; ritual; magician; sorcerer; seeress; vidyādhara; māyākāra; aindrajālika; non-literate 1. Introduction1 In the emergence of alternative religious systems such as tantrism, a number of factors have historically been seen at play. Among these are elements that might be called ‘pre-existing’. That is, they themselves are not representative of the eventual emergent system, but they provide some of the raw material—ritual, ideological, terminological, functional, or other—for its development. Indology, and in particular the study of Indian ritual, has been less than adroit at discussing such phenomena, especially when it may be designated or classified as ‘magical’ in some sense. -

Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Swamiji an Offering

ॐ श्रीगु셁भ्यो नमः JAGADGURU SRI JAYENDRA SARASWATHI SWAMIJI AN OFFERING P.R.KANNAN, M.Tech. Navi Mumbai Released during the SAHASRADINA SATHABHISHEKAM CELEBRATIONS of Jagadguru Sri JAYENDRA SARASWATHI SWAMIJI Sankaracharya of Moolamnaya Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Kanchipuram August 2016 Page 1 of 151 भक्तिर्ज्ञानं क्तिनीक्त ः शमदमसक्ति ं मञनसं ुक्तियुिं प्रर्ज्ञ क्तिेक्त सिं शुभगुणक्तिभिञ ऐक्तिकञमुक्तममकञश्च । प्रञप्ञः श्रीकञमकोटीमठ-क्तिमलगुरोयास्य पञदञर्ानञन्मे स्य श्री पञदपे भि ु कृक्त ररयं पुमपमञलञसमञनञ ॥ May this garland of flowers adorn the lotus feet of the ever-pure Guru of Sri Kamakoti Matham, whose worship has bestowed on me devotion, supreme experience, humility, control of sense organs and thought, contented mind, awareness, knowledge and all glorious and auspicious qualities for life here and hereafter. Acknowledgements: This compilation derives information from many sources including, chiefly ‘Kanchi Kosh’ published on 31st March 2004 by Kanchi Kamakoti Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamiji Peetarohana Swarna Jayanti Mahotsav Trust, ‘Sri Jayendra Vijayam’ (in Tamil) – parts 1 and 2 by Sri M.Jaya Senthilnathan, published by Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham, and ‘Jayendra Vani’ – Vol. I and II published in 2003 by Kanchi Kamakoti Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamiji Peetarohana Swarna Jayanti Mahotsav Trust. The author expresses his gratitude for all the assistance obtained in putting together this compilation. Author: P.R. Kannan, M.Tech., Navi Mumbai. Mob: 9860750020; email: [email protected] Page 2 of 151 P.R.Kannan of Navi Mumbai, our Srimatham’s very dear disciple, has been rendering valuable service by translating many books from Itihasas, Puranas and Smritis into Tamil and English as instructed by Sri Acharya Swamiji and publishing them in Internet and many spiritual magazines. -

Branding Yoga the Cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga

ANDREA R. JAIN Branding yoga The cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga n October 1989, long-time yoga student, John Friend modern soteriological yoga system based on ideas and (b. 1959) travelled to India to study with yoga mas- practices primarily derived from tantra. The encounter Iters. First, he went to Pune for a one-month intensive profoundly transformed Friend, and Chidvilasananda in- postural yoga programme at the Ramamani Iyengar itiated him into Siddha Yoga (Williamson forthcoming). Memor ial Yoga Institute, founded by a world-famous yoga proponent, B. K. S. Iyengar (b. 1918). Postural yoga (De Michelis 2005, Singleton 2010) refers to mod- Friend spent the next seven years deepening his ern biomechanical systems of yoga, which are based understanding of both Iyengar Yoga and Siddha Yoga. on sequences of asana or postures that are, through He gained two Iyengar Yoga teaching certificates and pranayama or ‘breathing exercises’, synchronized with taught Iyengar Yoga in Houston, Texas. Every sum- 1 the breath. Following Friend’s training in Iyengar Yoga, mer, he travelled to Siddha Yoga’s Shree Muktananda he travelled to Ganeshpuri, India where he met Chid- Ashram in upstate New York, where he would study 1954 vilasananda (b. ), the current guru of Siddha Yoga, for one to three months at a time. at the Gurudev Siddha Peeth ashram.2 Siddha Yoga is a Friend founded his own postural yoga system, Anusara Yoga, in 1997 in The Woodlands, a high- 1 Focusing on English-speaking milieus beginning in end Houston suburb. Anusara Yoga quickly became the 1950s, Elizabeth De Michelis categorizes modern one of the most popular yoga systems in the world. -

Mantra and Yantra in Indian Medicine and Alchemy

Ancient Science of Life Vol. VIII, Nos. 1. July 1988, Pages 20-24 MANTRA AND YANTRA IN INDIAN MEDICINE AND ALCHEMY ARION ROSU Centre national de la recherché scientifique, Paris (France) Received: 30 September1987 Accepted: 18 December 1987 ABSTRACT: This paper was presented at the International Workshop on mantras and ritual diagrams in Hinduism, held in Paris, 21-22 June1984. The complete text in French, which appeared in the Journal asiatique 1986, p.203, is based upon an analysis of Ayurvedc literature from ancient times down to the present and of numerous Sanskrit sources concerning he specialized sciences: alchemy and latrochemisry, veterinary medicine as well as agricultural and horticulture techniques. Traditional Indian medicine which, like all possession, were deeply rooted in their Indian branches of learning, is connected consciousness. The presence of these in with the Vedas and him Atharvaveda in medical literature is less a result of direct particular, is a rational medicine. From the Vedic recollections than of their persistence time of he first mahor treatises, those of in the Hindu tradition, a fact to which testify Caraka and Susruta which may be dated to non-medical Sanskrit texts (the Puranas and the beginning of the Christian era, classical Tantra) with regard to infantile possession. Ayurveda has borne witness to its scientific Scientific doctrines and with one another in tradition. While Sanskrit medical literature the same minds. The general tendency on bears the stamp of Vedic speculations the part of the vaidyas was nevertheless to regarding physiology, its dependence on limit, in their writings, such popular Vedic pathology is insignificant and wholly contributions so as to remain doctrines of negligible in the case of Vedic therapeutics. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

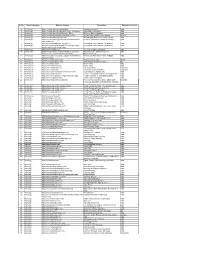

Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization Indus Valley Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 4 Archaelogy http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Post/881715 Ancient Vishnu Idol Found in Russia Russia 5 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/ Archeological Evidence of Vedic System India 6 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/scientific- Scientific Verification of Vedic Knowledge India verif-vedas.html 7 Archaelogy http://www.ariseindiaforum.org/?p=457 Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India 8 Archaelogy http://www.dwarkapath.blogspot.com/2010/12/why- Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India dwarka-submerged-in-water.html 9 Archaelogy http://www.harappa.com/ The Ancient Indus Civilization India 10 Archaelogy http://www.puratattva.in/2010/10/20/mahendravadi- Mahendravadi – Vishnu Temple of India vishnu-temvishnu templeple-of-mahendravarman-34.html of mahendravarman 34.html Mahendravarman 11 Archaelogy http://www.satyameva-jayate.org/2011/10/07/krishna- Krishna and Rath Yatra in Ancient Egypt India rathyatra-egypt/ 12 Archaelogy http://www.vedicempire.com/ Ancient Vedic heritage World 13 Architecture http://www.anishkapoor.com/ Anish Kapoor Architect London UK 14 Architecture http://www.ellora.ind.in/ Ellora Caves India 15 Architecture http://www.elloracaves.org/ Ellora Caves India 16 Architecture http://www.inbalistone.com/ Bali Stone Work Indonesia 17 Architecture http://www.nuarta.com/ The Artist - Nyoman Nuarta Indonesia 18 Architecture http://www.oocities.org/athens/2583/tht31.html Build temples in Agamic way India 19 Architecture http://www.sompuraa.com/ Hitesh H Sompuraa Architects & Sompura Art India 20 Architecture http://www.ssvt.org/about/TempleAchitecture.asp Temple Architect -V. -

Shaktipat Thesis for Dist

The Descent of Power: Possession, Mysticism, and Metaphysics in the Śaiva Theology of Abhinavagupta1 CHRISTOPHER D. WALLIS, M.A., M.PHIL. INTRODUCTION IT IS TO BE HOPED that the next ten years of Indological scholarship will demonstrate beyond dispute that Abhinavagupta, the great polymathic scholar and theologian of tenth-century Srīnagar, was one of the major figures in the history of Indian philosophy and religion, on par with such personages as Śaṅkara and Nāgārjuna. His importance as an expert in aesthetic philosophy and literary criticism has long been known to Sanskritists in both India and the West, and his contributions to the theories of rasa and dhvani continue to be studied. His stature as a theologian and metaphysical philosopher is just as great, though less recognized until recently. As the foremost among a number of skilled Kashmiri exegetes of various schools of the Śaiva religion, he did much to elevate Śaivism to a level of sophistication and comprehensive coherence unprecedented to that date, perhaps helping to ensure its continued patronage by royal courts and exegesis by learned scholars for centuries to come. With Muslim incursions beginning late in his 1 This paper could not have been written without two years of intensive study with Professor Alexis Sanderson of All Souls College, Oxford, whose scholarship has proved essential in advancing my understanding of Shaivism. Also very helpful was Dr. Somadeva Vasudeva, of the Clay Sanskrit Library, whose database and encyclopedic knowledge have been invaluable. The germ of the idea for this article was suggested to me when Professor Paul Muller-Ortega (University of Rochester) first pointed out to me the passage beginning at MVT 2.14. -

(Capricorn) MAKARA

www.astrologicalmagazine.com Inside We Shall Overcome: Editor's Note 2 Special Message from 5 His Holiness Gurudev Sri Sri Ravi Shankar Cover Mars in Capricorn. Coronavirus Pandemic and Story Forecast and Remedies 7 Cure. The Role of Nakshatras 10 Coronavirus: The Miraculous Health Benefits Effects of Solar and Lunar Eclipse12 of 17 Vishnu Sasasranama Why Coronavirus The Role of Saturn, Mars, Began in China? 22 Rahu and the 24 Eighth House in Epidemics Coronavirus Words of Wisdom 28 27 Naadi Astrology Based Analysis The Astrological eMagazine Panchanga 32 for May 2020 This Month (May 2020) The Astrological for You 35 eMagazine Ephemeris 40 for May 2020 1 May 2020 THE ASTROLOGICAL eMAGAZINE www.astrologicalmagazine.com Editor’s Note Niranjan Babu & Suprajarama Raman Dear Readers, व नो अया अमतत धो३ऽिभशतरव पिध व don’t blindly believe in what is ं े ु े ृ । ं न ऊती तव िचया िधया िशा शिच गातिवत ु ् ॥ being told but use your common The impact of the COVID-19 crisis sense and intelligence to infer, and has just begun to reveal itself. The This verse is a part of the hymns for c) Shiksha – self discipline. pandemic is raging a threat beyond Lord Indra. Indra governs all our all boundaries, medically and Indriyas – or faculties that help us During the times of Coronavirus, e c o n o m i c a l l y. D e v e l o p i n g sense, observe and recognize the let’s use this verse as Gospel and countries like India have fewer and various events and happenings fight together this pandemic. -

To Download the Book

OM SRI GURUBHYO NAMAH from Tamil book by Pu.Ma.JAYASENTHILNATHAN, M.A. (Asthana Vidvan, Sri Sankara Matham, Kanchipuram) and other sources Released during the SAHASRADINA SATHABHISHEKAM CELEBRATIONS of Jagadguru Sri JAYENDRA SARASWATHI SWAMIGAL Sankaracharya of Moolamnaya Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Kanchipuram November 2015 Compiler’s Preface The unbounded Grace of Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Swamigal, Sankaracharya of Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham has made me take up the impossible task of compiling his Vijaya Yatras based on Sri Pulavar Ma.Jayasenthilnathan’s book in Tamil ‘Sri Jayendra Vijayam’ – parts 1 and 2. The contents of the two volumes have been assembled and abridged. Information has also been updated, mainly in the Appendices based on other sources. A multifaceted personality, simplicity personified- that is our Swamigal in a nutshell. His one trait, which none, who has had his fleeting darshan even once, will miss is his geniality and the infectious and bewitching smile on his lustrous face. The revered Paramacharya Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Swamigal had said that he himself was the “Iccha Sakthi” and his disciple was the “Kriya Sakthi”. This was with reference to how his devoted disciple carried out his every wish. Soon after his becoming Peethadhipati, Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Swamigal wrote Page 2 of 128 a treatise on Brahma Sutra Bhashya, titled ‘Gurupriya’, as desired by his Guru. Known for clarity, cogency and brevity, Gurupriya is intended to serve as a refresher to the serious student engaged in manana, contemplation. Sri Acharya Swamigal has become the prime mover over the years in projects that have far - reaching impact in manifold areas of Vedic education, maintenance of heritage including temples, social welfare, health, child care, and village crafts and education. -

Energetic Rejuvenation Newsle

EnergeticRejuvenation.com E-Newsletter Vol. 2 No. 3 3/2009 Copyright © 2009 Anton Baraschi In this issue: Editorial ………………………………………………………………………………………………….pg 1 News and Links ………………………………………………………………………………………….pg 2 Feature Article –Fearless Living-Seven Steps for Overcoming Our Fears – by Santi Meunier...………...pg 2 Healer of the Month – Rainer Niederkofler- Water as Medicine ………………........................................pg 6 Interview- A Spiritual Psychiatrist - Kenneth Porter MD………………….…………………………..….pg 12 Book Review- Entangled Minds- Extrasensory Experiences in a Quantum Reality- by Dean Radin…….pg 14 DVD Review – Soul Masters: Dr. Guo & Dr. Sha……………………………………….………………..pg 15 DVD Review- The Living Matrix- The New Science of Healing....………….………….………………..pg 15 DVD Review- Stardreams- a feature documentary exploring the mystery of the crop circles...…...……..pg 15 Announcements ……………………………………………………...…………………………………....pg 15 Credits..………………………………………………………………………………………………........ pg 15 Editorial Spring in our hearts The framework of nature echoes in our souls, inspiring rejuvenation. After all we are an intrinsic part of Nature. If Nature could rejuvenate, so could we. In the Book Review, an intriguing title: "Entangled Minds" by Dean Radin. The quantum physics extrapolation seems to gain ground. We are ALL connected. The Healer of the Month is practicing a technique that would be incomprehensible if it were not for the physicists models. One of the DVD's featured- about Chinese Masters shows long distance treatments- from China to USA. This too would be incomprehensible if it were not for those brave scientists, like Dean Radin. The other featured DVD (The Living Matrix) interviews a cross section of luminaries of the Quantum Effect without which energy healing would be Woo-woo, magic or entertainment. We would see the effects, but dismiss them because our rationality does not accept what we don’t understand. -

Faces of Nondualism

Faces of Nondualism By Swami Jnaneshvara This paper is created to help the participants of the Center for Nondualism and Abhyasa Ashram better understand the wide range of principles and practices related to Nondualism (The paper will be revised from time to time to make it ever more clear). Although there is ultimately only one Nondual reality, people approach the direct realization of this through a variety of faces. Following are brief descriptions of many, if not most of these approaches. By exploring the breadth of approaches, we can better understand our own chosen path to direct experience of the Nondual Reality, Truth, Source, or other such ways of denoting this. Individual seekers will find much greater depth within his or her own tradition. Unfortunately, from lack of understanding some people incorrectly believe nondualism to be “against” dualism, whereas dualism is actually an essential aspect of the journey towards realization in direct experience of the Nondual Reality, Truth, or Beingness. Gently, lovingly one treads the path of life in the world towards the knowing of that Nonduality which is both beyond and yet inclusive of the world. There is no separateness, no division. It is only due to ignorance (avidya) that there appears to be separateness and division where there is actually seamless Nondual Reality. Nondualism is a minority worldview in our times. In the U.S. especially, the dominant worldview is that of dualistic Christian monotheism. It is in large part for this reason that people of the Nondualism perspective can benefit from coming together in a spirit of friendship to explore the principles and practices of the various paths leading to nondual experience. -

Self Awakening Volume 2 Issue 3

Self Awakening Maha Yoga - Simplest, no -cost and highest method of self -realization February 1, 2010 Volume 2, Issue 3 E Editor’s note Dear Readers: The purpose of this quarterly newsletter, Self Awakening, is to inform Sadhaks (seekers of self-realization) and other readers about Maha Yoga, a very simple, no cost and effective method of self-realization. P. P. Shri Narayan Kaka Maharaj of Nashik, India is a leading teacher and exponent of Maha Yoga, a centuries old tradition, Contents whereby a realized Guru (Siddha Guru) awakens the Universal Li fe Energy (Kundalini) within the Sadhak, eventually leading him/her Editor’s note 1 to self-realization. Our Maha Yoga Lineage 2 To the thousands of Sadhaks in the Maha Yoga tradition all over Churning of the Heart 7 the world and other interested readers, this e-newsletter is Answers to questions 20 intended to provide virtual Satsang. It is intended to help keep Universal Brotherhood Day 25 Sadhaks engaged in Maha Yoga, be informed about Maha Yoga- related events around the world, and to provide a forum for Upcoming events 26 getting guidance about Maha Yoga from P. P. Shri Kaka Maharaj What’s new 27 and other Maha Yoga leaders. How to contribute content 27 As I have mentioned in previous issues of Self Awakening, the success of this e-newsletter will depend upon Sadhak participation through their contribution of content. Sadhaks are therefore encouraged to contribute news about Maha Yoga- related events in their parts of the world, thoughtful articles and life experiences (not experiences during Sadhan), questions about Maha Yoga and their Sadhan (practice) they would like addressed, and any comments and suggestions regarding this e-newsletter.