Hartnett's Panels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middle-Road Congo Plan Is Offered UN by Bilateral Group

IM7I I Independent Dally I SH 14010 |HU<4 atlir. lisadtT uroufh rndtr. atciBd Ciui ft 7c PER COPY SSc PER WEEK VOL. 83, NO. 162 FaU U R»d Bank ao4 a AMUlonl MtiUof OWCM. RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 1961 BY CARRIER PAGE ONE Salary Boosts ^^^ i . Middle-Road Congo Planned; Police Plan Is Offered UN Request More NEW SHREWSBURY — An ordinance providing By Bilateral Group pay raises for policemen, some borough employees and laborers was introduced last night by the Borough Council. ns Priest Slain Hope to Avert The measure, which will have • public hearing In KIVM Terror March 2, lists increases Storm U.S. Direct Clash for Jerome Reed, borough USUMBURA, Ruaada-Urundi (AP) — Congolese soldiers on clerk, up $400 to $6,100; Embassy the rampage killed • Belgian Of East-West Mrs. Ruth B. Crawford, To Pick Catholic priest yesterday in tax collector, up $300 to LAGOS, Nigeria (AP) — Bukavu, capital o( the Congo'* UNITED NATIONS, N. $5,500; Mrs. M. Jeannette Cobb, The American and Belgian Klvu Province, and arrested Y. (AP)—A group of Asian municipal court clerk, up $1,000 and beat up Anicet Kashamura, GOP Slate CONKRINCI AT THI UNITID NATIONS — Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin, left, Embassies were stormed and African nations moved to $2,400; Ernest Hiltbrunner, the No. 2 man of the pro-Com- today to seize the initiative road and sanitation department •nd Altksei E. Neiterenko, center, • member of the Soviet delegation, confera with ast night by screaming munist Lumumbist regime in supervisor, up $200 to $7,200, and Omar Loutfi, delegate from the United Arab Republic, before meeting of U.N. -

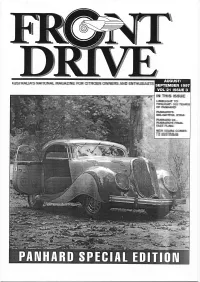

IN THIS ISSUE LIMELIGHT to TWILIGHT.Loo YEARS of PANHARD PANHARD's DELIGHTFUL DYNA PANHARD 24

AUSTRALIAS NATIONAL MAGAZINE FOR CITROEN OWNERS AND ENTHUSIASTS IN THIS ISSUE LIMELIGHT TO TWILIGHT.lOO YEARS OF PANHARD PANHARD'S DELIGHTFUL DYNA PANHARD 24 . PANHARD'S FINAL FAST FLING NEW XSARA COMES TO AUSTR,qLh FRC)NT DRTVE - AIJSTRALTA'S NATIONAL CITROEN MAGAZINE Published by The Gitro6n Classic Owners CIub of Australia lnc. CITROEN C].ASSIC OWNERS CLUB NANCE CI.ARKE 1984 OF AUSTRALIA INC. CCOCA MEMBERSHIP JACK WEAVER 1991 The Glub's and Front Drive's postal address is Annual Membership $30 P.O. Box 52, Deepdene Delivery Centre, Overseas Postage Add $g Victoria, 3103. CCOCA MEETINGS Our e-mail address is [email protected] Every fourth Wednesday of the month, except CCOCA lnc. is a member of the Association of December. Motoring Clubs. G.P.O. Box 2374V Melboume, Venue:- Canterbury Sports Ground Pavilion, Victoria, 3000. cnr. Chatham and Guilford Roads, publication The views expressed in this are not Canterlcury Victoria. Melways Ref 46 F10, necessarily those of CCOCA or its committee. Neither CCOCA, nor its Committee can accept any responsibility for any mechanical advice printed in, or adopted from Front Drive. And that means you can now pay for your subscriptions, rally fees, and not Ytsfr to mention the all important spare pafts in a mone convenient way 1997 COCCA COMMITTEE "What is that thing on the cover?", I hear you ask. I know it is not PRESIDENT - Peter Fitzgerald a Citro6n, it actually has nothing to do with Citro6n at all. But its 297 Moray Street, South Melbourne, younger siblings'do. lt is a Panhard Dynamic Type 140 for this Victoria, 3205 photograph a good deal the other Panhard material in Phone (03) s6e6 0866 (BH & AH) and, of Fa,r (03) 9696 0708 this issue I must thank Bruce Dickie. -

March / April 2018 Issue

SAHJournal ISSUE 291 MARCH / APRIL 2018 SAH Journal No. 291 • March / April 2018 $5.00 US1 Contents 3 PRESIDENT’S PERSPECTIVE SAHJournal 4 CENTURY OF AUSTRALIAN AUTOMOBILE MANUFACTURE ENDS ISSUE 291 • MARCH/APRIL 2018 A HISTORICAL REVIEW AND PERSPECTIVE 8 SAH IN PARIS XXIII THE SOCIETY OF AUTOMOTIVE HISTORIANS, INC. 9 RÉTROMOBILE 43 An Affiliate of the American Historical Association 11 BOOK REVIEWS Billboard Officers Louis F. Fourie President SAH Board Nominations: related to Rolls-Royce of America, Inc. This Edward Garten Vice President Robert Casey Secretary The SAH Nominating Committee is includes promotional images of Rolls-Royce Rubén L. Verdés Treasurer seeking nominations for positions on the automobiles photographed by John Adams board through 2021. Please address all Davis. Other automotive history subjects Board of Directors nominations to the chair, Andrew Beckman are sought too. Only digital images are Andrew Beckman (ex-officio) ∆ Robert G. Barr ∆ at [email protected]. needed. Accordingly, if you would like your H. Donald Capps # antique automotive documents and photos Donald J. Keefe ∆ Wanted: Contributors! The SAH digitized for free, just contact the editor at Kevin Kirbitz # Journal invites contributors for articles and [email protected] to confirm the assign- Carla R. Lesh † book reviews. (A book reviewer that can read ment. Then mail your material, and it will be John A. Marino # Robert Merlis † Japanese is currently needed.) Please contact mailed back to you with the digital media. Matthew Short ∆ the editor directly. Thank you! Vince Wright † Your Billboard: What are you Terms through October (†) 2018, (∆) 2019, and (#) 2020 Correction: The masthead of issues working on?.. -

Transnational Corporate Planning And

1 52 JOURNAL OF AUSTRALIAN POLITICAL ECONOMY No. 34 1111111111111111111111 950303037 Walker, R.G., "The Cumn Report -A Response", Report to Prospect County Council, January 1993a. I TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATE PLANNING J Walker, R.G., "Evaluating the financial performance of Australian water authorities", in , AND NATIONAL INDUSTRIAL PLANNING: M. Johnson and S. Rix (eds), Water in Australia, Pluto Press in associativn with the Public \ Sector Research Centre, University ofNSW, 1993b. THE CASE OF THE FORD MOTOR Walker, R.G., "A feeling of deja vu: controversies in accounting and auditing regulation f COMPANY IN AUSTRALIA] in Australia", Critical Perspectives on Accounting, I993c. pp. 97-109. ~ Woo, L. & H.P. Lange, "Equity raising by Australian small business: a study ofaccess and survival", Small Enterprise Research Journal. 1992. ~ Jerry Courvisanos Keep Informed About L~ur Issues! ~ ~\ x ...... >..., ... .... >.<" l ,~, \..(: .......;x. ~ Ford Australia made two announcements on the 9th February 1994. One If':'f::::: \ was for the closure of the Sydney Assembly Plant at Homebush in fr;~~' September 1994, and the end of production of the Ford Laser. The other . ·:I},)'i-" ....; \:,\i\\_" was that the Ford Capri sports car would cease production in May 1994. ~'" j . ;;- • " .....fl.O" .. This created much media interest for a couple of days, and then the issue ~'f;,....~\ '., 1J.r '.:':'to.'~.l Studj~ ~ disappeared. A few days earlier Mitsubishi confinned plans to inject Labour Briefing is " quat1erly \ . ~ publication containing summaries from a '\8 $500 million in the development and production of a new Magna model wide range of journals and magazines covering for 1996, with continued export to Europe and the V.S. -

RMIT Design Archive Journal Volume 5 No 1 2015

RMIT DESIGN ARCHIVES JOURNAL VOL 5 Nº 1 2015 Early Automotive Design ARTICLES in Australia EDITORIAL Norman Darwin 4–16 Interview: Phillip Zmood Tony Lupton 17–23 Women in the Early Australian Automotive Industry: A Survey Judith Glover & Harriet Edquist 24–35 EXHIBITION Shifting Gear: Design, Innovation REVIEW and the Australian Car National Gallery of Victoria Tony Lupton 36–39 rmit design archives journal Journal Editor Harriet Edquist Editorial Assistance Kaye Ashton Design Letterbox.net.au Editorial Board Suzie Attiwill rmit University Michael Bogle Sydney, nsw Nanette Carter Swinburne University Liam Fennessy rmit University Christine Garnaut University of South Australia Philip Goad University of Melbourne Brad Haylock rmit University Robyn Healy rmit University Andrew Leach Griffith University, qld Catherine Moriarty University of Brighton, uk Michael Spooner rmit University Laurene Vaughan rmit University contact Cover and this page [email protected] Phillip Zmood, www.rmit.edu.au/designarchives drawings of styling exercises for HQ issn 1838-9406 Monaro Coupe Published by rmit Design Archives, rmit University roof concept. Text © rmit Design Archives, rmit University and individual authors. This Journal is copyright. RMIT Design Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of research, Archives criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means without the prior permission of the publisher. This issue of the rmit Design Archives Journal focuses on the Australian car and in particular on its design. Its genesis lies in research undertaken for the Shifting Gear: Design, Innovation and the Australian Car exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, a curatorial collaboration with David Hurlston, Senior Curator of Australian Art at the ngv. -

5950 *850 5 Ywks Drive Wedge Into Axis Defense

^ w x ^ b fS ttT lEtfntMa H m ilb Mra. Dorothy Tedford o f 189 Blreh atreet left laat evening for Benefit ShoV\ To Show^ilm IlibontTown Ooldaboro. N. to Join her hua* Heard Along Main Street Tires and Tubes Certified band, Pfc. Frederick Tedford who Barw d Ro«d Brtdg* Onb la ataUoned at Seymour Johnson For^ied Cross t. Mary’s Held, training at the Air Oorpa on Some o f Manchester*g Side Streets^ Too __ attbt at tlM horn* Mr. By Local Ration Board I mechanical achool. Mra. Walter LaUajr and an- I aa aranlnf ot eontraet. Tba Capacity C>oyd Attract A wave of lestic bartering in^been carrying on denpite many Unusual Movie to Fol DurinF the week ending March 4>Veigh, 130 Pearl street, one tire; Group No. 8 the Memorial M for the armlnc war* Mra. Manchester is iwing. It all handicapa. 19 the following certiflcaiee were Joseph hicnsegUo, 80 School street, 1 Martin and Walter Lailajr, Hoapital Women’a auxUlary, Mra. ed by Entertainment at came, about due H o,^e food ra "It could happen here." What low Lenten Vesper, iMued by the local War Price and one tire; Earl R. Nevers, throe D. M. Caldwell, leader, will meet tioning. Some peoplSL like tea, a different story it would be if tires; Stephen J. Pongrantx, 498 Monday afternoon at two o’clock The South Metl^dlst." Service at the Church. Rationing Board for tires and Oottlon Dlmlow. of South Wlnd- others like butter; stUV^ere are enemy planes did glide out of the East Middle turnpike, oiM t in ; at the hoapiUL Members of. -

Loose Fillings #45 SPRING 2013 1 Standing ¼ Mile 13.8 Seconds

Historic air-cooled racing cars in Australia and beyond IN THIS ISSUE ... • Brabham’s Cooper LOOSELOOSE • Tales of Tassie Coopers • Cooper Suspension • Bearings and Housings FILLINGSFILLINGS • Bits and Pieces Rob Saward has been investigating ... JACK BRABHAM’S RELIABLE V-TWIN COOPER By early 1953 there were 17 Coopers little did he know what he was letting Mt Druitt) the car was stopped successively in Australia, 11 of them with ‘big twin’ himself in for. From his first appearance at by a dropped valve, magneto failure engines. The new circuit at Mt Druitt was Castlereagh Sprints in June 1952 and two and magneto drive problems. However becoming the hotbed of Cooper racing, circuit meetings, the last at Parramatta Park Brabham was a methodical chap and he where the cars were very fast in the short where he broke a conrod in practice, he did sorted the problems one by one. At the races, but none seemed able to run at speed very few miles with the car. In September, Druitt meeting on February 12 1953, when for long; retirement rates were high. When Brabham discarded the hybrid single and the photo below (from the Graham Howard Jack Brabham bought his one-owner, one- fitted a Vincent twin. His first appearance Collection) was taken by O.C.Turner for the meeting, no-engine Cooper Mk4 sometime at King Edward Park hillclimb in October ARDC, it all came together. The Brabham before June 1952 (can anyone pinpoint the showed promise but a high first gear hurt Cooper ran well for 5 races and went home date?) and installed the BSA/JAP 500cc his times. -

Front Wheel Drive the Story of Pioneers of the Front Wheel Drive Motorcar

Front Wheel Drive The story of pioneers of the front wheel drive motorcar To most British motorists that think about such things, the Mini, was the beginning of the front wheel drive revolution. The revolutionary concept that was the Mini was it’s packaging.The packing of the engine, gearbox and final drive into a very compact unit, leaving sufficient space in a very small car for four people. The Mini didn’t start the front wheel drive revolution but the packaging revolution that has spread throughout the worlds motor industry. This was made possible because of the developments in front wheel drive technology that had gone on during the previous forty years, but until that time had been almost ignored by the British motor industry. The combination of front wheel drive and efficient packaging has revolutionised the world’s motor industry, being almost universally used, except were considerations of cost and or size are not important. This is the story of those years before the Mini and the pioneers of front wheel drive. From the Carriage to the Horseless Carriage For the thousands of years, from the time of their invention, wheeled vehicles were pulled from the front. This was because it was an inherently stable arrangement, it made steering easier and gave maximum control. This lasted as long as the foot was used to transmit the motive power to the road, but once the wheel was used to transmit the power of an onboard engine to the road the situation changed. This was due to the correct and universal understanding that the front wheels must be used for steering, and as it was so much simpler to drive the none steerable wheels, rear wheel drive became the accepted method used for the pioneer self propelled vehicle. -

HISTORY AUSTRALIA's OWN CAR Part

HISTORY AUSTRALIA’S OWN CAR Part Two Wwick Budd With General Motors now in control of Holden’s, Edward Holden remained at the helm. In August 1931 he was appointed joint managing director of GMH and later the sole managing director following the introduction of a new administration structure. Some Standard agents in Australia continued to use Holden bodies and initially it was business as usual as the 1930s rolled on and the economy continued to improve. In March 1934, General Motors appointed Lawrence Hartnett as the new managing director. Edward Holden was removed from his manager’s position but remained the chairman of directors. He subsequently held this position until ill health forced his resignation in 1947. He was reported to be ‘bitter and disappointed’ at his removal from the day to day running of the company and turned his attention to other business interests. From 1935 he served in the Legislative Council of South Australia and was knighted for his services in 1945. With Edward Holden effectively sidelined, the choice of Hartnett was a logical decision by GM and would prove to be an interesting one from an Australian point of view. Hartnett was born and educated in England and came to the attention of GM management while working as a field representative for the company in southern India. After some training in the US he achieved good results in their Swedish operation and his entrepreneurial skills led to his appointment to the board of Vauxhall Motors Ltd in the UK. According to one biographer, Hartnett was given the job of reforming GMH. -

Hartnett's Panels

Hartnett’s Car – Passion or Folly Dr. Norman A Darwin Abstract When Laurence J Hartnett arrived at GM-H in March 1934 as Managing Director he gave little thought to making his own car. This rapidly changed as Holden’s fortunes improved to the point where GM-H, under Hartnett’s leadership, would begin planning an all-Australian car for a 1943 introduction. The war was a diversion until the end of 1944 when Hartnett directed his engineers back to designing and building a new vehicle, one that would carry the name Holden. Hartnett’s car – Passion or Folly explores Hartnett’s dream to produce an automobile he could rightly claim as his own. Sadly, for Hartnett, the Holden’s success happened after his resignation and Hartnett’s dream faltered, then turned into a passion following the formation of the Hartnett Motor Company Ltd, a firm that ended in tatters. The story of the Hartnett car has often been told with rumour, inuendo, myth, conspiracy and malpractice. Hartnett’s Car will examine these factors to determine if “The Passion” was in reality a “Folly”. Was the Hartnett car worth the effort and agony? Was the design right for Australia? No doubt Hartnett would argue, yes but there are dissenters. These questions are raised, explored and answered considering the competition and market of the era. Sir Laurence, as time has revealed, was a brilliant entrepreneur, an innovator, a motivator who has been described as a technocratic brigand, a man who did not give up his dream without a fight. His contribution to the Australian Automobile Industry is significant and the exact circumstances surrounding the Hartnett car’s failure is long overdue. -

Trade Policy Review Mechanism Australia

RESTRICTED GENERAL AGREEMENT C/RM/S/43 6 January 1994 ON TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution (94-0020) COUNCIL TRADE POLICY REVIEW MECHANISM AUSTRALIA Report by the Secretariat In pursuance of the CONTRACTING PARTIES' Decision of 12 April 1989 concerning the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (BISD 36S/403), the Secretariat submits herewith its report on Australia. The report is drawn up by the Secretariat on its own responsibility. It is based on the information available to the Secretariat and that provided by Australia. As required by the Decision, in preparing its report the Secretariat has sought clarification from Australia on its trade policies and practices. Document C/RM/G/43 contains the report submitted by the Government of Australia. NOTE TO ALL DELEGATIONS Until further notice, this document is subject to a press embargo AustraIiaAustralia C/RM/S/43 . g CONTENTS Page SUMMARY OBSERVATIONS vii (1) The Economic Environment vii (2) Institutional Framework vii (3) Trade Policy Features and Trends viii (i) Evolution since the initial review viii (ii) Type and incidence of trade policy instruments ix (iii) Temporary measures ix (iv) Sectoral policy patterns x (4) Trade Policies and Foreign Trading Partners xi I. THE ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT (1) Recent Economic Performance and Policy Objectives 1 (2) Trade Performance 7 (3) Outlook 12 II. TRADE POLICY REGIME: FRAMEWORK AND OBJECTIVES 14 (1) Introduction 14 (2) Structure of Trade Policy Formulation and Implementation 14 (i) Institutional structure at Commonwealth level 14 (ii) Commonwealth-State relations 16 (iii) Legal status of GATT obligations 21 (iv) Advisory and review bodies 21 (3) Trade Policy Objectives 23 (4) Preferential Trade Relations and Regional Cooperation 24 (i) Preferential trade 24 (ii) Regional cooperation initiatives 29 C/RM/S/43 Trade Policy Review Mechanisim Page iv III FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT AND TRADE 30 (1) General Policy Direction 30 (2) Legal Framework and Procedures 31 (3) Trends in Inward and Outward Foreign Direct Investment 31 IV. -

The Australian Gothic Through the Novels of Sonya Hartnett

1 The Australian Gothic Through the Novels of Sonya Hartnett R. Miller Award: PhD Date: 2018 2 The Australian Gothic Through the Novels of Sonya Hartnett R. Miller A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 University of Worcester 3 Abstract The Australian Gothic Through the Novels of Sonya Hartnett Melbourne author Sonya Hartnett, adapts and updates the Australian Gothic within narratives that focus on individual subjectivities to bring to scrutiny the abuses that children suffer due to the invisibility of normative, hegemonic and conformist discourses. This study argues that Hartnett re-locates the colonial trope of the lost child from the wild setting of the bush to cultural topographies in the modern Australian context. The study’s theoretical approach combines concepts from phenomenology, cultural geography and spectral studies to form an hauntology which is articulated and applied to detailed analyses of eleven of Hartnett’s novels set in Australia. The conceptual framework is explained in chapter one and the remaining chapters group Hartnett’s novels thematically and in relation to the settings inhabited by her young protagonists. This structure enables the consideration of the dialectical relationship between places ‘exterior’ to the subject such as the Australian suburb or country town and the psychological ‘interior’ of the mind. Furthermore the study proposes that phenomenological experiences of place, space and time are central aspects of Hartnett’s