A Performance Guide for Thomas Pasatieri's Bel Canto Songs For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

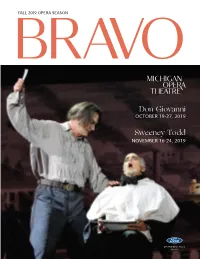

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2013

ARTICLE Part II: Reproductions of Drawings and Paintings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors Section B: Collections and Selections Part III: Commercial Engravings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors William Blake and His Circle: Part IV: Catalogues and Bibliographies A Checklist of Publications and Section A: Individual Catalogues Section B: Collections and Selections Discoveries in 2013 Part V: Books Owned by William Blake the Poet Part VI: Criticism, Biography, and Scholarly Studies By G. E. Bentley, Jr. Division II: Blake’s Circle Blake Publications and Discoveries in 2013 with the assistance of Hikari Sato for Japanese publications and of Fernando 1 The checklist of Blake publications recorded in 2013 in- Castanedo for Spanish publications cludes works in French, German, Japanese, Russian, Span- ish, and Ukrainian, and there are doctoral dissertations G. E. Bentley, Jr. ([email protected]) is try- from Birmingham, Cambridge, City University of New ing to learn how to recognize the many styles of hand- York, Florida State, Hiroshima, Maryland, Northwestern, writing of a professional calligrapher like Blake, who Oxford, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Voronezh used four distinct hands in The Four Zoas. State, and Wrocław. The Folio Society facsimile of Blake’s designs for Gray’s Poems and the detailed records of “Sale Editors’ notes: Catalogues of Blake’s Works 1791-2013” are likely to prove The invaluable Bentley checklist has grown to the point to be among the most lastingly valuable of the works listed. where we are unable to publish it in its entirety. All the material will be incorporated into the cumulative Gallica “William Blake and His Circle” and “Sale Catalogues of William Blake’s Works” on the Bentley Blake Collection 2 A wonderful resource new to me is Gallica <http://gallica. -

William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: from Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W. Winkleblack Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Winkleblack, Robert W., "William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence" (1977). Masters Theses. 3328. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3328 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. �S"Date J /_'117 Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��--��- Date Author pdm WILLIAM BLAKE'S SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE: - FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE TO WISE INNOCENCE (TITLE) BY Robert W . -

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry Paul Kiparsky Stanford University [email protected] Linguistics Department, Stanford University, CA. 94305-2150 July 19, 2009 Review (4872 words) The publication of this joint book by the founder of generative metrics and a distinguished literary linguist is a major event.1 F&H take a fresh look at much familiar material, and introduce an eye-opening collection of metrical systems from world literature into the theoretical discourse. The complex analyses are clearly presented, and illustrated with detailed derivations. A guest chapter by Carlos Piera offers an insightful survey of Southern Romance metrics. Like almost all versions of generative metrics, F&H adopt the three-way distinction between what Jakobson called VERSE DESIGN, VERSE INSTANCE, and DELIVERY INSTANCE.2 F&H’s the- ory maps abstract grid patterns onto the linguistically determined properties of texts. In that sense, it is a kind of template-matching theory. The mapping imposes constraints on the distribution of texts, which define their metrical form. Recitation may or may not reflect meter, according to conventional stylized norms, but the meter of a text itself is invariant, however it is pronounced or sung. Where F&H differ from everyone else is in denying the centrality of rhythm in meter, and char- acterizing the abstract templates and their relationship to the text by a combination of constraints and processes modeled on Halle/Idsardi-style metrical phonology. F&H say that lineation and length restrictions are the primary property of verse, and rhythm is epiphenomenal, “a property of the way a sequence of words is read or performed” (p. -

[email protected] BERNARD LABADIE to RETU

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 26, 2016 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] BERNARD LABADIE TO RETURN TO NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC TO CONDUCT ALL-MOZART PROGRAM Flute Concerto No. 2 with Principal Flute ROBERT LANGEVIN Exsultate, jubilate with Soprano YING FANG in Her Philharmonic Debut Symphony No. 31, Paris Symphony No. 39 December 1–3, 2016 Bernard Labadie will return to the New York Philharmonic to conduct an all-Mozart program: the Flute Concerto No. 2, with Principal Flute Robert Langevin as soloist; Exsultate, jubilate with soprano Ying Fang in her Philharmonic debut; Symphony No. 31, Paris; and Symphony No. 39. The program takes place Thursday, December 1, 2016, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, December 2 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, December 3 at 8:00 p.m. The concerts open with three youthful works written when Mozart was 17, 21, and 22 years old, and close with the darker Symphony No. 39, written three years before his death. A leading specialist in the Baroque and Classical repertoire, Bernard Labadie led Mozart’s Requiem in his most recent appearance with the Philharmonic, in November 2013. The New York Times described this performance as “glowing … one of the most cohesive I have heard.” These concerts will mark Principal Flute Robert Langevin’s first of Mozart’s Flute Concerto No. 2 with the Philharmonic. Soprano Ying Fang has been acclaimed for her performances of Mozart, including her Metropolitan Opera debut in The Marriage of Figaro in September 2014, and Don Giovanni with The Juilliard School in April 2012. -

Alicia Ostriker, Ed., William Blake: the Complete Poems

REVIEW Alicia Ostriker, ed., William Blake: The Complete Poems John Kilgore Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue 4, Spring 1979, pp. 268-270 268 psychological—carried by Turner's sublimely because I find myself in partial disagreement with overwhelming sun/god/king/father. And Paulson argues Arnheim's contention "that any organized entity, in that the vortex structure within which this sun order to be grasped as a whole by the mind, must be characteristically appears grows as much out of translated into the synoptic condition of space." verbal signs and ideas ("turner"'s name, his barber- Arnheim seems to believe, not only that all memory father's whorled pole) as out of Turner's early images of temporal experiences are spatial, but that sketches of vortically copulating bodies. Paulson's they are also synoptic, i.e. instantaneously psychoanalytical speculations are carried to an perceptible as a comprehensive whole. I would like extreme by R. F. Storch who argues, somewhat to suggest instead that all spatial images, however simplistically, that Shelley's and Turner's static and complete as objects, are experienced tendencies to abstraction can be equated with an temporally by the human mind. In other works, we alternation between aggression toward women and a "read" a painting or piece of sculpture or building dream-fantasy of total love. Storch then applauds in much the same way as we read a page. After Constable's and Wordsworth's "sobriety" at the isolating the object to be read, we begin at the expense of Shelley's and Turner's overly upper left, move our eyes across and down the object; dissociated object-relations, a position that many when this scanning process is complete, we return to will find controversial. -

2017–2018 Season Artist Index

2017–2018 Season Artist Index Following is an alphabetical list of artists and ensembles performing in Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage (SA/PS), Zankel Hall (ZH), and Weill Recital Hall (WRH) during Carnegie Hall’s 2017–2018 season. Corresponding concert date(s) and concert titles are also included. For full program information, please refer to the 2017–2018 chronological listing of events. Adès, Thomas 10/15/2017 Thomas Adès and Friends (ZH) Aimard, Pierre-Laurent 3/8/2018 Pierre-Laurent Aimard (SA/PS) Alarm Will Sound 3/16/2018 Alarm Will Sound (ZH) Altstaedt, Nicolas 2/28/2018 Nicolas Altstaedt / Fazil Say (WRH) American Composers Orchestra 12/8/2017 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) 4/6/2018 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) Anderson, Laurie 2/8/2018 Nico Muhly and Friends Investigate the Glass Archive (ZH) Angeli, Paolo 1/26/2018 Paolo Angeli (ZH) Ansell, Steven 4/13/2018 Boston Symphony Orchestra (SA/PS) Apollon Musagète Quartet 2/16/2018 Apollon Musagète Quartet (WRH) Apollo’s Fire 3/22/2018 Apollo’s Fire (ZH) Arcángel 3/17/2018 Andalusian Voices: Carmen Linares, Marina Heredia, and Arcángel (SA/PS) Archibald, Jane 3/25/2018 The English Concert (SA/PS) Argerich, Martha 10/20/2017 Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (SA/PS) 3/22/2018 Itzhak Perlman / Martha Argerich (SA/PS) Artemis Quartet 4/10/2018 Artemis Quartet (ZH) Atwood, Jim 2/27/2018 Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra (SA/PS) Ax, Emanuel 2/22/2018 Emanuel Ax / Leonidas Kavakos / Yo-Yo Ma (SA/PS) 5/10/2018 Emanuel Ax (SA/PS) Babayan, Sergei 3/1/2018 Daniil -

Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in the Four Zoas

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1983 Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Michael Ackland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.173-189 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Ackland: Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas by MICHAEL ACKLAND RIZEN is at once one of Blake's most easily recognizable characters U and one of his most elusive. Pictured often as a grey, stern, hover ing eminence, his wide-outspread arms suggest oppression, stultifica tion, and limitation. He is the cruel, jealous patriarch of this world, the Nobodaddy-boogey man-god evoked to quieten the child, to still the rabble, to repress the questing intellect. At other times in Blake's evolv ing mythology he is an inferior demiurge, responsible for this botched and fallen creation. In political terms, he can project the repressive, warmongering spirit of Pitt's England, or the collective forces of social tyranny. More fundamentally, he is a personal attribute: nobody's daddy because everyone creates him. As one possible derivation of his name suggests, he is "your horizon," or those impulses in each of us which, through their falsely assumed authority, limit all man's other capabilities. Yet Urizen can, at times, earn our grudging admiration. -

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There are two general forms we will concern ourselves with: verse and prose. Verse is metered, prose is not. Poetry is a genre, or type (from the Latin genus, meaning kind or race; a category). Other genres include drama, fiction, biography, etc. POETRY. Poetry is described formally by its foot, line, and stanza. 1. Foot. Iambic, trochaic, dactylic, etc. 2. Line. Monometer, dimeter, trimeter, tetramerter, Alexandrine, etc. 3. Stanza. Sonnet, ballad, elegy, sestet, couplet, etc. Each of these designations may give rise to a particular tradition; for example, the sonnet, which gives rise to famous sequences, such as those of Shakespeare. The following list is taken from entries in Lewis Turco, The New Book of Forms (Univ. Press of New England, 1986). Acrostic. First letters of first lines read vertically spell something. Alcaic. (Greek) acephalous iamb, followed by two trochees and two dactyls (x2), then acephalous iamb and four trochees (x1), then two dactyls and two trochees. Alexandrine. A line of iambic hexameter. Ballad. Any meter, any rhyme; stanza usually a4b3c4b3. Think Bob Dylan. Ballade. French. Line usually 8-10 syllables; stanza of 28 lines, divided into 3 octaves and 1 quatrain, called the envoy. The last line of each stanza is the refrain. Versions include Ballade supreme, chant royal, and huitaine. Bob and Wheel. English form. Stanza is a quintet; the fifth line is enjambed, and is continued by the first line of the next stanza, usually shorter, which rhymes with lines 3 and 5. Example is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. -

Topical Weill: News and Events

Volume 27 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 2009 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news & news events Summertime Treats Londoners will have the rare opportunity to see and hear three Weill stage works within a two-week period in June. The festivities start off at the Barbican on 13 June, when Die Dreigroschenoper will be per- formed in concert by Klangforum Wien with HK Gruber conducting. The starry cast includes Ian Bostridge (Macheath), Dorothea Röschmann (Polly), and Angelika Kirchschlager (Jenny). On 14 June, the Lost Musicals Trust begins a six-performance run of Johnny Johnson at Sadler’s Wells; Ian Marshall Fisher directs, Chris Walker conducts, with Max Gold as Johnny. And the Southbank Centre pre- sents Lost in the Stars on 23 and 24 June with the BBC Concert Orchestra. Charles Hazlewood conducts and Jude Kelly directs. It won’t be necessary to travel to London for Klangforum Wien’s Dreigroschenoper: other European performances are scheduled in Hamburg (Laeiszhalle, 11 June), Paris (Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, 14 June), and back in the Klangforum’s hometown, Vienna (Konzerthaus, 16 June). Another performing group traveling to for- eign parts is the Berliner Ensemble, which brings its Robert Wilson production of Die Dreigroschenoper to the Bergen Festival in Norway (30 May and 1 June). And New Yorkers will have their own rare opportunity when the York Theater’s “Musicals in Mufti” presents Knickerbocker Holiday (26–28 June). Notable summer performances of Die sieben Todsünden will take place at Cincinnati May Festival, with James Conlon, conductor, and Patti LuPone, Anna I (22 May); at the Arts Festival of Northern Norway, Harstad, with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra led by HK Gruber and Ute Gfrerer as Anna I (20 June); and in Metz, with the Orchestre National de Lorraine, Jacques Mercier, conductor, and Helen Schneider, Anna I (26 June). -

Singing in English in the 21St Century: a Study Comparing

SINGING IN ENGLISH IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A STUDY COMPARING AND APPLYING THE TENETS OF MADELEINE MARSHALL AND KATHRYN LABOUFF Helen Dewey Reikofski Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2015 APPROVED:….……………….. Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor Stephen Dubberly, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Committee Member Stephen Austin, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Vocal Studies … James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Reikofski, Helen Dewey. Singing in English in the 21st Century: A Study Comparing and Applying the Tenets of Madeleine Marshall and Kathryn LaBouff. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2015, 171 pp., 6 tables, 21 figures, bibliography, 141 titles. The English diction texts by Madeleine Marshall and Kathryn LaBouff are two of the most acclaimed manuals on singing in this language. Differences in style between the two have separated proponents to be primarily devoted to one or the other. An in- depth study, comparing the precepts of both authors, and applying their principles, has resulted in an understanding of their common ground, as well as the need for the more comprehensive information, included by LaBouff, on singing in the dialect of American Standard, and changes in current Received Pronunciation, for British works, and Mid- Atlantic dialect, for English language works not specifically North American or British. Chapter 1 introduces Marshall and The Singer’s Manual of English Diction, and LaBouff and Singing and Communicating in English. An overview of selected works from Opera America’s resources exemplifies the need for three dialects in standardized English training. -

John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens

2011 NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20506-0001 John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens Robert Ward Robert Ward NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 2011 John Conklin’s set design sketch for San Francisco Opera’s production of The Ring Cycle. Image courtesy of John Conklin ii 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Contents 1 Welcome from the NEA Chairman 2 Greetings from NEA Director of Music and Opera 3 Greetings from OPERA America President/CEO 4 Opera in America by Patrick J. Smith 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 12 John Conklin Scenic and Costume Designer 16 Speight Jenkins General Director 20 Risë Stevens Mezzo-soprano 24 Robert Ward Composer PREVIOUS NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 2010 30 Martina Arroyo Soprano 32 David DiChiera General Director 34 Philip Glass Composer 36 Eve Queler Music Director 2009 38 John Adams Composer 40 Frank Corsaro Stage Director/Librettist 42 Marilyn Horne Mezzo-soprano 44 Lotfi Mansouri General Director 46 Julius Rudel Conductor 2008 48 Carlisle Floyd Composer/Librettist 50 Richard Gaddes General Director 52 James Levine Music Director/Conductor 54 Leontyne Price Soprano 56 NEA Support of Opera 59 Acknowledgments 60 Credits 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS iii iv 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Welcome from the NEA Chairman ot long ago, opera was considered American opera exists thanks in no to reside within an ivory tower, the small part to this year’s honorees, each of mainstay of those with European whom has made the art form accessible to N tastes and a sizable bankroll.