Palestinian Refugees in Exile Country Profiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reading in the Zionist Theory of Knowledge “Epistemology” Through the Writings of Ye- Houda Shenhav Shahrabani

A Reading in the Zionist Theory of Knowledge “Epistemology” Through the Writings of Ye- houda Shenhav Shahrabani Omar Al Tamimi Yehouda Shenhav Shahrabani. The Arab Jews: A Post-Colonial Reading of Nationalism, Religion, and Ethnicity. Translated by Yasin Al Sayed. Ramallah: the Palestinian Forum for Israeli Studies; Madar. 2016, 372 pages About the problematic naming, and the importance of the writer There are many intertwined studies and literature that discuss the subject of the Oriental Jews, and try to portray a picture of them, before and after their arrival to Israel. Many researchers have defines the Jews of the Orient by calling them similar names. Shlomo Svirsky says: “usually, the Israeli public in general, and particularly researchers of social studies call these Jews “the Oriental group or community” (Edot Hamizrach, Mizracheem). On the other hand, other researchers portray a different image, in contrary to the popular Israeli academic conceptions, trying to question and counteract the Zionist epistemology. Yehouda Shaharbani is a professor of sociology and anthropology at Tel Aviv University and a researcher at the Van Leer Institute. Shaharbani emphasizes the importance of naming this group the “Arab Jews”, for his conviction that the Arab state of being among the Arab Jews was manipulated and obliterated through what he defines as the “national methodology”, which we will tackle through this review. Although he believes that the concept of the Arab Jews is ambiguous and characterized by suspicion and perplexity (p. 37) as a result of the rift in the Jewish-Arab relations, nonetheless, one cannot overlook the history, customs, and culture that the two parties share. -

Palestinian Gefugees

SPECIAL BULLETIN May 2001 INTRODUCTION & HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The Palestinian refugee problem was created as a result of In the course of the June War of 1967 (An-Naqsa), the remaining two wars - the War of 1948 and the June 1967 War. The War of parts of Arab Palestine (along with the Syrian Golan Heights and 1948 (An-Naqba) was triggered by the UN General Assembly Egypt's Sinai Peninsula), came under Israeli occupation, and some (UNGA) Res. 181 of 29 Nov. 1947 ('Partition Plan') that allocated 300,000 Palestinians were displaced from the West Bank and Gaza 56.47% of Palestine to the Jewish state, at a time when Jews Strip, including around 175,000 UNRWA-registered refugees who were less than one-third of the population and owned no more were to flee for a second time. To accommodate the new wave of than 7% of the land. The war resulted in the creation of the displaced persons ten extra refugee camps were established. state of Israel in 78% of Palestine, and the uprooting of the Throughout the occupation, Israeli policies have followed a systematic indigenous Palestinian population from their homeland by pattern of land confiscation and other discriminatory measures aimed military force, expulsion or fear of massacres and other attacks at forcing even more Palestinians to leave their homeland. The seizure perpetrated by Jewish underground and militant groups such of land and property and their transferal to new Jewish immigrants as Haganah, Irgun, and Stern Gang. and Israeli settlers is backed by a series of laws enacted to prevent After the war, the newly established UN Conciliation the return and resettlement of the rightful owners (e.g., Absentee Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) estimated that 726,000 Property Law). -

Palestinian Refugees: Adiscussion ·Paper

Palestinian Refugees: ADiscussion ·Paper Prepared by Dr. Jan Abu Shakrah for The Middle East Program/ Peacebuilding Unit American Friends Service Committee l ! ) I I I ' I I I I I : Contents Preface ................................................................................................... Prologue.................................................................................................. 1 Introduction . .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 The Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem .. .. .. .. .. 3 • Identifying Palestinian Refugees • Counting Palestinian Refugees • Current Location and Living Conditions of the Refugees Principles: The International Legal Framework .... .. ... .. .. ..... .. .. ....... ........... 9 • United Nations Resolutions Specific to Palestinian Refugees • Special Status of Palestinian Refugees in International Law • Challenges to the International Legal Framework Proposals for Resolution of the Refugee Problem ...................................... 15 • The Refugees in the Context of the Middle East Peace Process • Proposed Solutions and Principles Espoused by Israelis and Palestinians Return Statehood Compensation Resettlement Work of non-governmental organizations................................................. 26 • Awareness-Building and Advocacy Work • Humanitarian Assistance and Development • Solidarity With Right of Return and Restitution Conclusion .... ..... ..... ......... ... ....... ..... ....... ....... ....... ... ......... .. .. ... .. ............ -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Boundary & Territory Briefing

International Boundaries Research Unit BOUNDARY & TERRITORY BRIEFING Volume 1 Number 8 The Evolution of the Egypt-Israel Boundary: From Colonial Foundations to Peaceful Borders Nurit Kliot Boundary and Territory Briefing Volume 1 Number 8 ISBN 1-897643-17-9 1995 The Evolution of the Egypt-Israel Boundary: From Colonial Foundations to Peaceful Borders by Nurit Kliot Edited by Clive Schofield International Boundaries Research Unit Department of Geography University of Durham South Road Durham DH1 3LE UK Tel: UK + 44 (0) 191 334 1961 Fax: UK +44 (0) 191 334 1962 E-mail: [email protected] www: http://www-ibru.dur.ac.uk The Author N. Kliot is a Professor and Chairperson of the Department of Geography, University of Haifa, and Head of the Centre for Natural Resources Studies at the University of Haifa. Her specialistion is political geography, and she is a member of the International Geographical Union (IGU) Commission on Political Geography. She writes extensively on the Middle East and among her recent publications are: Water Resources and Conflict in the Middle East (Routledge, 1994) and The Political Geography of Conflict and Peace (Belhaven, 1991) which she edited with S. Waterman. The opinions contained herein are those of the author and are not to be construed as those of IBRU Contents Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Development of the Egypt-Palestine Border, 1906-1918 1 2.1 Background to delimitation 1 2.2 The Turco-Egyptian boundary agreement of 1906 4 2.3 The delimitation of the Egypt-Palestine boundary 7 2.4 The demarcation of the Egypt-Palestine boundary 7 2.5 Concluding remarks on the development of the Egypt- Palestine border of 1906 8 3. -

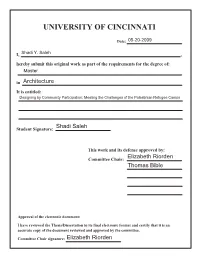

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 05-20-2009 I, Shadi Y. Saleh , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture It is entitled: Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps Shadi Saleh Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Elizabeth Riorden Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Architecture In the school of Architecture and Interior design Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2009 By Shadi Y. Saleh Committee chair Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible ABSTRACT Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria are the result of the sudden population displacements of 1948 and 1967. After 60 years, unorganized urban growth compounds the situation. The absence of state support pushed the refugees to take matters into their own hands. Currently the camps have problems stemming from both the social situation and the degradation of the built environment. Keeping the refugee camps in order to “represent” a nation in exile does not mean to me that there should be no development. The thesis seeks to make a contribution in solving the social and environmental problems in a way that emphasizes the Right of Return. -

Rethinking Palestinian Refugee Communities in Pre-War Syria and the Right of Return

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Rethinking Palestinian Refugee Communities in Pre-War Syria and the Right of Return Eliza Wincombe Cornwell Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Cornwell, Eliza Wincombe, "Rethinking Palestinian Refugee Communities in Pre-War Syria and the Right of Return" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 367. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/367 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Palestinian Refugee Communities in Pre-War Syria and the Right of Return Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Eliza Cornwell Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Michelle Murray and Dina Ramadan for unending support and encouragement throughout my time at Bard. I would also like to thank Kevin Duong for helping me formulate my ideas, for inspiring me to write and re-write, and for continuously giving me a sense of purpose and accomplishment in completing this project. -

Occupied Palestinian Territory (Including East Jerusalem)

Reporting period: 29 March - 4 April 2016 Weekly Highlights For the first week in almost six months there have been no Palestinian nor Israeli fatalities recorded. 88 Palestinians, including 18 children, were injured by Israeli forces across the oPt. The majority of injuries (76 per cent) were recorded during demonstrations marking ‘Land Day’ on 30 March, including six injured next to the perimeter fence in the Gaza Strip, followed by search and arrest operations. The latter included raids in Azzun ‘Atma (Qalqiliya) and Ya’bad (Jenin) involving property damage and the confiscation of two vehicles, and a forced entry into a school in Ras Al Amud in East Jerusalem. On 30 occasions, Israeli forces opened fire in the Access Restricted Area (ARA) at land and sea in Gaza, injuring two Palestinians as far as 350 meters from the fence. Additionally, Israeli naval forces shelled a fishing boat west of Rafah city, destroying it completely. Israeli forces continued to ban the passage of Palestinian males between 15 and 25 years old through two checkpoints controlling access to the H2 area of Hebron city. This comes in addition to other severe restrictions on Palestinian access to this area in place since October 2015. During the reporting period, Israeli forces removed the restrictions imposed last week on Beit Fajjar village (Bethlehem), which prevented most residents from exiting and entering the village. This came following a Palestinian attack on Israeli soldiers near Salfit, during which the suspected perpetrators were killed. Israeli forces also opened the western entrance to Hebron city, which connects to road 35 and to the commercial checkpoint of Tarqumiya. -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

The Truth About the Struggle of the Palestinians in the 48 Regions

The truth about the struggle of the Palestinians in the 48 regions By: Wehbe Badarni – Arab Workers union – Nazareth Let's start from here. The image about the Palestinians in the 48 regions very distorted, as shown by the Israeli and Western media and, unfortunately, the .Palestinian Authority plays an important role in it. Palestinians who remained in the 48 regions after the establishment of the State of Israel, remained in the Galilee, the Triangle and the Negev in the south, there are the .majority of the Palestinian Bedouin who live in the Negev. the Palestinians in these areas became under Israeli military rule until 1966. During this period the Palestinian established national movements in the 48 regions, the most important of these movements was "ALARD" movement, which called for the establishment of a democratic secular state on the land of Palestine, the Israeli authorities imposed house arrest, imprisonment and deportation active on this national movement, especially in Nazareth town, and eventually was taken out of .the law for "security" reasons. It is true that the Palestinians in the 48 regions carried the Israeli citizenship or forced into it, but they saw themselves as an integral part of the Palestinian Arab people, are part and an integral part of the Palestinian national movement, hundreds of Palestinians youth in this region has been joined the Palestinian .resistance movements in Lebanon in the years of the sixties and seventies. it is not true that the Palestinians are "Jews and Israelis live within an oasis of democracy", and perhaps the coming years after the end of military rule in 1966 will prove that the Palestinians in these areas have paid their blood in order to preserve their Palestinian identity, in order to stay on their land . -

UNRWA-Weekly-Syria-Crisis-Report

UNRWA Weekly Syria Crisis Report, 15 July 2013 REGIONAL OVERVIEW Conflict is increasingly encroaching on UNRWA camps with shelling and clashes continuing to take place near to and within a number of camps. A reported 8 Palestine Refugees (PR) were killed in Syria this week as a result including 1 UNRWA staff member, highlighting their unique vulnerability, with refugee camps often theatres of war. At least 44,000 PR homes have been damaged by conflict and over 50% of all registered PR are now displaced, either within Syria or to neighbouring countries. Approximately 235,000 refugees are displaced in Syria with over 200,000 in Damascus, around 6600 in Aleppo, 4500 in Latakia, 3050 in Hama, 6400 in Homs and 13,100 in Dera’a. 71,000 PR from Syria (PRS) have approached UNRWA for assistance in Lebanon and 8057 (+120 from last week) in Jordan. UNRWA tracks reports of PRS in Egypt, Turkey, Gaza and UNHCR reports up to 1000 fled to Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. 1. SYRIA Displacement UNRWA is sheltering over 8317 Syrians (+157 from last week) in 19 Agency facilities with a near identical increase with the previous week. Of this 6986 (84%, +132 from last week and nearly triple the increase of the previous week) are PR (see table 1). This follows a fairly constant trend since April ranging from 8005 to a high of 8400 in May. The number of IDPs in UNRWA facilities has not varied greatly since the beginning of the year with the lowest figure 7571 recorded in early January. A further 4294 PR (+75 from last week whereas the week before was ‐3) are being sheltered in 10 non‐ UNRWA facilities in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus. -

The Earless Children of the Stone

REFUGEE PARTICIPATION NETWORK 7 nvxi February 1990 Published by Refugee Studies Programme, Queen Elizabeth House, 21 St Giles, OXFORD OX1 3LA, UK. THE EARLESS CHILDREN OF THE STONE ££££ ;0Uli: lil Sr«iiKKiJi3'^?liU^iQ^^:;fv'-' » <y * C''l* I WW 'tli' (Cbl UUrHfill'i $ J ?ttoiy#j illCiXSa * •Illl •l A Palestinian Mother of Fifteen Children: 7 nave fen sons, eacn wi// nave ten more so one hundred will throw stones' * No copyright. MENTAL HEALTH CONTENTS THE INTIFADA: SOME PSYCHOLOGICAL Mental Health 2 CONSEQUENCES * The Intifada: Some Psychological Consequences * The Fearless Children of the Stone The End of Ramadan * Testimony and Psychotherapy: a Reply to Buus and Agger riday was a busy day in the town of Gaza, with many people F out in the streets buying food in preparation for the celebration ending Ramadan. The unified Leadership of Palestine Refugee Voices from Indochina 8 had issued a clandestine decree that shops could stay open until 5 * Forced or Voluntary Repatriation? p.m., and that people should stay calm during the day of the feast. * What is it Like to be a Refugee in They were not to throw stones at the soldiers while Site 2 Refugee Camp on the demonstrating. On their side, the Israeli authorities were said to have promised to keep their soldiers away from the refugee Thai-Cambodian Border? camps. Later, the matron of Al Ahli Arab general hospital * Some Conversations from Site 2 confessed that she had nonetheless kept her staff on full alert. Camp * Return to Vietnam In the early morning of Saturday, 6 May we awoke to cracks of gunfire and the rumble of low flying helicopters.