The Princeton Theological Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theology Catalog February 2014

Theology Catalog February 2014 Windows Booksellers 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 1 Eugene, OR 97401 USA Phone: (800) 779-1701 or (541) 485-0014 * Fax: (541) 465-9694 Email and Skype: [email protected] Website: http://www.windowsbooks.com Monday - Friday: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Pacific time (phone & in-store); Saturday: Noon to 3:00 PM, Pacific time (in-store only- sorry, no phone). Our specialty is used and out-of-print academic books in the areas of theology, church history, biblical studies, and western philosophy. We operate an open shop and coffee house in downtown Eugene. Please stop by if you're ever in the area! When ordering, please reference our book number (shown in brackets at the end of each listing). Prepayment required of individuals. Credit cards: Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover; or check/money order in US dollars. Books will be reserved 10 days while awaiting payment. Purchase orders accepted for institutional orders. Shipping charge is based on estimated final weight of package, and calculated at the shipper's actual cost, plus $1.00 handling per package. We advise insuring orders of $100.00 or more. Insurance is available at 5% of the order's total, before shipping. Uninsured orders of $100.00 or more are sent at the customer's risk. Returns are accepted on the basis of inaccurate description. Please call before returning an item. __ARCIC-I Revisited: An Evaluation and a Revision__. Catholic Press Association. 1985. Paperback. 102pp. Foxing. Else good. $11 [422653] . __Army and Religion: An Inquiry and Its Bearing upon the Religious Life of the Nation__. -

Seminary Resources

PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 2008-2009 Catalogue VOLUME XXXII Princeton Theological Seminary Catalogue This catalogue is an account of the academic year 2007–2008 and an announcement of the proposed program for the 2008–2009 academic year. The projected program for 2008–2009 is subject to change without notice and is in no way binding upon the Seminary. The Seminary has adopted significant changes to its curriculum for 2008–2009 and future years. Tuition and fees listed herein cover the 2008–2009 academic year and are subject to change in subsequent years without notice. Princeton Theological Seminary does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, ancestry, sex, age, marital status, national or ethnic origin, or disability in its admission policies and educational programs. The senior vice president of the Seminary (Administration Building, Business Office 609.497.7700) has been designated to handle inquiries and grievances under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 and other federal nondiscrimination statutes. ACCREDITATION The Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Higher Education Philadelphia, PA 19104 215.662.5606 www.middlestates.org The Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada 10 Summit Park Drive Pittsburgh, PA 15275-1103 412.788.6505 www.ats.edu @ 2008 Princeton Theological Seminary. All rights reserved as to text, drawings, and photographs. Republication in whole or part is prohibited. Princeton Theological Seminary, the Princeton Seminary Catalogue, and the logos of Princeton Theological Seminary are all trademarks of Princeton Theological Seminary. Excerpts from Hugh T. Kerr, ed. Sons of the Prophets: Leaders in Protestantism from Princeton Seminary, Copyright ©1963 by Princeton University Press, reprinted with permission. -

The Revival of Systematic Theology an Overview

Since the late 197Os, the field of systematic theology has been home to an explosion of diverse efforts to produce major dogmatic works: the evangelical, the ecumenical, and the experiential. In assessing the value of such works, however; the norm remains the same: whether they strengthen the life of the church and its witness toJesus Christ. The Revival of Systematic Theology An Overview Gabriel Fackre Professor of Christian Theology Andover Newton Theological School fh EARLIER GENERATION of pastors cut their eyeteeth on the systematic theology of Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, and Paul Tillich.’ Or, short of the giants, a Gustaf Aulen or Louis Berkhof might have found its way onto study shelves.” In those days, theologians were writing comprehensive works, and students, clergy, and church leaders were reading them. It was generally assumed that responsible preaching and teaching in congregations could not be done without careful study of the foundational materials, and that meant “systematic theology” as the visiting of the loci, the “common places” of Christian belief. The towering figures passed from the scene and with them the writing-and also the reading-of this genre. The 1960s and 1970s brought ad hoc theology to the fore. Theological “bits and pieces” or “theology and . .” were the order of the day. Some on the Continent did continue to write weighty multi-volume works, especially in the Lutheran and Reformed traditions, which were translated and used in a few seminaries in this country: Helmut Thielicke, Otto Weber, and G. C. Berkouwer.’ But systematics classes in mainline academia that sought current homegrown products had only a few to assign students, notably John Interpretation 229 Macquarrie’s Princzples of Christian Theology, Gordon Kaufman’s Systematic Theology: A Historicist Perspective, and Shirley Guthrie’s Christian Doctrirz4 Then came the deluge. -

In Defense of Christian Faith and a Democratic Future on the Trump Presidency: from Members of the Princeton Seminary Faculty Fe

In Defense of Christian Faith and a Democratic Future On the Trump Presidency: From Members of the Princeton Seminary Faculty February 24, 2017 (signers to this statement do not represent the Seminary or the faculty as a whole) We, the undersigned, believe that because God is sovereign over all creation and because all human beings are embraced by God’s all encompassing grace, the god of Donald Trump’s “America first” nationalism is not the God revealed in our scriptures. Regardless of our specific political persuasions we agree that the attitudes fostered by this nationalism are inconsistent with Christian values of welcoming the stranger as if we were welcoming Christ, of seeking to distinguish truth from deception and conceit, and of believing that no institution or government can demand the kind of loyalty that belongs only to God. We also believe that the policies and approach embraced by the Trump administration run counter to democratic values, as executive orders and members of the new administration’s cabinet often seek to demonize Islam, foster white supremacy, compromise the rule of law and intimidate judges, undermine the empowerment of women, ignore the destruction of the environment, promote homophobia, unleash unfounded fears of crime that worsen the “law and order” abuses of police and security forces. We reject the pervasive aim of placing the monetary gain of wealthy classes over the welfare of its citizenry by undermining education, quality employment, and health care. We believe that Christian faith and US democracy are not the same thing; hence, we stand against the notion of a “Christian nation.” But as Christians who are also citizens or residents of the US, we stand against the attitudes and policies that are being fostered in this present political climate. -

2007 Additional Meetings (San Diego)

2007 Additional Meetings (San Diego) Program Book Text Time and room assignments are subject to change; final time and room assignments are available in the onsite Annual Meeting Program At-A-Glance. Location Key: CC San Diego Convention Center GH Manchester Grand Hyatt HG Hilton Gaslamp MG San Diego Marriott Gaslamp MM San Diego Marriott Hotel & Marina OH Omni San Diego Hotel M15-50 Seventh Day Adventist Religion Chairs Thursday - 1:00 pm-6:30 pm MM-Torrance M15-51 Society of Anglican and Lutheran Theologians Thursday - 1:00 pm-6:30 pm MM-Leucadia Oceanside Pacific Point Loma Leucadia Theme: Thinking Scripturally: The Bible and Theology 2:00 pm-3:30 pm Carol Newsom, Emory University Three Perspectives on Good and Evil: The Bible’s Internal Dialogue 4:00 pm-5:30 pm How Should Scripture Inform Thinking about Sexuality? Panelists: Marit Trelstead, Pacific Lutheran University John Hoffmeyer, Lutheran Seminary at Philadelphia Ian McFarland, Emory University 6:30 pm-8:30 pm Dinner The Society of Anglican and Lutheran Theologians (SALT) is an informal network of scholars and pastors committed to ongoing theological inquiry in the context of these two denominational families. Our annual meeting is held just prior to the AAR and SBL meeting. Most of our 250 members teach and/or pastor in seminaries, colleges, or churches; others are active in SALT to remain connected to colleagues in their own denominational cultures. We welcome other interested persons. For more information: [email protected]. M15-52 United Methodist Women of Color Scholars Program Thursday - 1:00 pm-6:30 pm GH-Del Mar M15-101 Hispanic Theological Initiative Consortium Reception Thursday - 5:00 pm-6:00 pm MM-Warner Center M15-102 Hispanic Theological Initiative Consortium Dinner Thursday - 6:00 pm-9:00 pm MM-Coronado M15-103 Adventist Society for Religious Studies, Section 1 Thursday - 7:00 pm-11:00 pm CC-25B Today through Saturday, the Adventist Society for Religious Studies will address the topic Adventism and Community. -

5.00 Theology List November 2013

$5.00 Theology List November 2013 Windows Booksellers 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 1 Eugene, OR 97401 USA Phone: (800) 779-1701 or (541) 485-0014 * Fax: (541) 465-9694 Email and Skype: [email protected] Website: http://www.windowsbooks.com Monday - Friday: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Pacific time (phone & in-store); Saturday: Noon to 3:00 PM, Pacific time (in-store only- sorry, no phone). Our specialty is used and out-of-print academic books in the areas of theology, church history, biblical studies, and western philosophy. We operate an open shop and coffee house in downtown Eugene. Please stop by if you're ever in the area! When ordering, please reference our book number (shown in brackets at the end of each listing). Prepayment required of individuals. Credit cards: Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover; or check/money order in US dollars. Books will be reserved 10 days while awaiting payment. Purchase orders accepted for institutional orders. Shipping charge is based on estimated final weight of package, and calculated at the shipper's actual cost, plus $1.00 handling per package. We advise insuring orders of $100.00 or more. Insurance is available at 5% of the order's total, before shipping. Uninsured orders of $100.00 or more are sent at the customer's risk. Returns are accepted on the basis of inaccurate description. Please call before returning an item. __A New Catechism: Catholic Faith for Adults__. Herder & Herder. 1967. Paperback. 510pp. VG/G. Worn dust jacket, else good. $5 [VL7931] . __Approaches Toward Unity: Papers Presented for Discussion at Joint Meetings of Protestant Episcopal and Methodist Commissions__. -

2010–2011 Catalogue

PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 2010–2011 Catalogue VOLUME XXXIV Princeton Theological Seminary Catalogue This catalogue is an account of the academic year 2009-2010 and an announcement of the proposed program for the 2010-2011 and 2011-2012 academic years. The projected programs for 2010–2011 and 2011–2012 are subject to change without notice and are in no way binding upon the Seminary. Tuition and fees listed herein cover the 2010–2011 academic year and are subject to change in subsequent years without notice. Princeton Theological Seminary does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, ancestry, sex, age, marital status, national or ethnic origin, or disability in its admission policies and educational programs. The senior vice president of the Seminary (Administration Building, Business Office 609.497.7700) has been designated to handle inquiries and grievances under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 and other federal nondiscrimination statutes. ACCREDITATION The Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Higher Education Philadelphia, PA 19104 215.662.5606 www.middlestates.org The Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada 10 Summit Park Drive Pittsburgh, PA 15275-1103 412.788.6505 www.ats.edu @ 2010 Princeton Theological Seminary. All rights reserved as to text, drawings, and photographs. Republication in whole or part is prohibited. Princeton Theological Seminary, the Princeton Seminary Catalogue, and the logos of Princeton Theological Seminary are all trademarks of Princeton Theological Seminary. Excerpts from Hugh T. Kerr, ed. Sons of the Prophets: Leaders in Protestantism from Princeton Seminary, copyright ©1963 by Princeton University Press, reprinted with permission. -

The Myth of Ontological Human Sinfulness

THE MYTH OF ONTOLOGICAL HUMAN SINFULNESS: HOW THE NOTION THAT HUMANS ARE INHERENTLY SINFUL CONTRIBUTES TO THE INSTITUTIONAL SCAPEGOATING OF THE URBAN POOR ____________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Fresno Pacific University Biblical Seminary ____________________ In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Theology ____________________ by Ivan Christian Paz December 2015 © 2015 Ivan Christian Paz All Rights Reserved Accepted by the Faculty of the Fresno Pacific University Biblical Seminary in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Theology. ________________________________________ Dr. Mark D. Baker, Adviser ________________________________________ Dr. Valerie Rempel, Second Reader The views expressed in this thesis are those of the student and do not necessarily express the views of the Fresno Pacific University Biblical Seminary. I grant Hiebert Library permission to make this thesis available for use by its own patrons, as well as those of the broader community through inter-library loan. This use is understood to be within the limitations of copyright. ________________________________________ Ivan C. Paz ________________________________________ Date Abstract of: THE MYTH OF ONTOLOGICAL HUMAN SINFULNESS: HOW THE NOTION THAT HUMANS ARE INHERENTLY SINFUL CONTRIBUTES TO THE INSTITUTIONAL SCAPEGOATING OF THE URBAN POOR ____________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Fresno Pacific University Biblical Seminary ____________________ In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Theology ____________________ by Ivan Christian Paz December 2015 A culture of conflict generally exists in the U.S. between people of color who live in eco- nomically disadvantaged, urban neighborhoods—i.e. “the urban poor”—and the criminal justice system. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE MARK LEWIS TAYLOR Princeton Theological Seminary 64 Mercer Street, P.O. Box 821 Princeton, NJ 08542 Office: 609 497-7918 cell: 609 638-0806 ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2004 - Maxwell M. Upson Professor of Theology and Culture Princeton Theological Seminary 2004 - 2005 Research Fellow. Institute of Advanced Studies. University of Helsinki. Helsinki Finland. 2005 - 2011 Chair, Religion & Society Committee, Princeton Theological Seminary 1999 - 2004 Professor of Theology and Culture Princeton Theological Seminary 1988 - 1999 Associate Professor of Theology and Culture Princeton Theological Seminary 1982 - 1988 Assistant Professor of Theology Princeton Theological Seminary EDUCATION Ph.D. 1982. Theology. The University of Chicago Divinity School. Dissertation: "Religious Dimensions in Cultural Anthropology: The Religious in the Cross-Cultural Hermeneutics of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Marvin Harris." (Committee: David Tracy, Langdon Gilkey, Stephen Toulmin, George W. Stocking, Jr.) M.Div./ D.Min. 1977. Union Theological Seminary in Virginia, Richmond, VA B.A. 1973. Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, WA COMMUNITY ORGANIZING POSITIONS 2009 - Board Member, M.A. Program in Community Organizing, University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee, and the Autonomous University of Social Movements (AUSM), Chicago. One of the only full masters programs offered in the U.S. in “community organizing,” 1 sited in the Albany Park community of Chicago, IL. Run by Ph.D.-trained supervisors from UW-Milwaukee, from Mexico, and in Chicago. 1996 - Founder, now Co-Coordinator of EMAJ: Educators for Mumia Abu-Jamal. An advocacy and support group of U.S. and international educators for the journalist, jailhouse lawyer and author, Mumia Abu-Jamal. With an M.A. in Psychology (U.Cal/Dominguez Hills) and plans for his own doctoral work, Mr. -

JOINT APPENDIX VOLUME FOUR Ja0925-Ja1217 AMERICAN CIVIL

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF NEW JERSEY; UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST LEGISLATIVE MINISTRY OF NJ; GLORIA IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF SCHOR ANDERSEN; PENNY POSTEL; and NEW JERSEY WILLIAM FLYNN, APPELLATE DIVISION Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. No.: A-004399-13 ROCHELLE HENDRICKS, Secretary ON APPEAL FROM FINAL of Higher Education for the ADMINISTRATIVE ACTION BY THE State of New Jersey, in her OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF official capacity; and ANDREW HIGHER EDUCATION P. SIDAMON-ERISTOFF, State Treasurer, State of New SAT BELOW: Jersey, in his official ROCHELLE HENDRICKS, SECRETARY capacity, OF HIGHER EDUCATION Defendants-Respondents. JOINT APPENDIX VOLUME FOUR Ja0925-Ja1217 JOINT APPENDIX VOLUME ONE Beth Medrash Govoha of America Application for Building Our Future Bond Act Funding for Construction of Library and Research Center........................................JA0001 Response to Grant Application Requirements for all programs ............................................. JA0053 Governing Board Resolution .......................... JA0005 Approved Site Plan – Kleinman Family Campus Center .. JA0058 Color Site Plan – Klein Family Campus ............... JA0060 General Schematics .................................. JA0069 Artist’s Rendering .................................. JA0073 Project Construction Budget ......................... JA0075 Budget Review from Construction Manager ............. JA0077 Cost and Source of Revenue Chart .................... JA0103 Depreciation Schedule Report ........................ JA0105 Document and Answer Document -

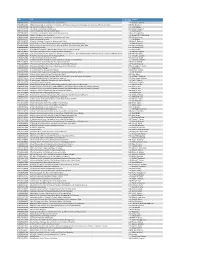

Spring Ebook Sale List Copy

ISBN Title Promo Price Author (USD) 2020 9781506433394 "After Ten Years": Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Our Times 4.99 Victoria J. Barnett 9781506418551 "Without Ceasing to be a Christian": A Catholic and Protestant Assess the Christological Contribution of Raimon PaniKKar 6.99 EriK Ranstrom 9781451407488 1 & 2 Corintios: 1 & 2 Corinthians 4.99 Efra'n Agosto 9781451419498 1 & 2 Kings: Continental Commentaries 4.99 Anselm Hagedorn 9781451426359 1 and 2 Corinthians: Texts @ Contexts series 4.99 Yung Suk Kim 9781506438405 1 Corinthians: An Exegetical and Contextual Commentary 4.99 Andrew Spurgeon 9781451424379 1 Enoch: The Hermeneia Translation 4.99 George W. E. Nickelsburg 9781451452334 4 Ezra and 2 Baruch: Translations, Introductions, and Notes 4.99 Matthias Henze 9781506450377 A Brief Introduction to Islam 4.99 Tim Dowley 9781451484342 A Case for Character: Towards a Lutheran Virtue Ethics 4.99 Joel D. Biermann 9781451487626 A Child Shall Lead Them: Martin Luther King Jr., Young People, and the Movement 4.99 Rufus Burrow Jr. 9781451496666 A Church Undone: Documents from the German Christian Faith Movement, 1932-1940 6.99 Mary M. Solberg 9781506400310 A Commentary on Acts 6.99 Yon Gyong Kwon 9781506406251 A Complicated Pregnancy: Whether Mary Was a Virgin and Why It Matters 4.99 Kyle Roberts 9781451496673 A Council for the Global Church: Receiving Vatican II in History 6.99 Massimo Faggioli 9781506416656 A Documentary History of Lutheranism, Volumes 1 and 2: Volume 1: From the Reformation to Pietism Volume 2: From the Enlightenment to the Present9.99 MarK Granquist 9781506401218 A Dual Reception: Eusebius and the Gospel of MarK 9.99 Clayton L. -

FP Spring 2019 List FOR

FORTRESS PRESS E-BOOK SALE Sale prices only available February 15-April 1, 2019 on Amazon.com or BarnesandNoble.com Title Series Author eISBN List Price Sale Price "After Ten Years": Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Our Times Victoria J. Barnett (Author) 9781506433394 $15.99 $4.99 "Without Ceasing to be a Christian": A CathoLic and Protestant Assess the ChristoLogicaL Contribution of Raimon Erik Ranstrom (Author); Bob Robinson (Author) 9781506418551 $77.99 $6.99 Panikkar 1 & 2 Corintios: 1 & 2 Corinthians Conozca su BibLia Efra'n Agosto (Editor) 9781451407488 $15.00 $4.99 1 & 2 Kings: ContinentaL Commentaries ContinentaL Commentaries AnseLm Hagedorn (Author); VoLkmar Fritz (Editor) 9781451419498 $49.00 $4.99 1 and 2 Corinthians: TeXts @ ConteXts series TeXts @ ConteXts Yung Suk Kim (Author) 9781451426359 $49.00 $4.99 1 Corinthians: An EXegeticaL and ConteXtuaL Commentary Andrew Spurgeon (Author) 9781506438405 $24.99 $4.99 George W. E. NickeLsburg (Author); James C. 1 Enoch: The Hermeneia TransLation 9781451424379 $18.00 $4.99 VanderKam (Author) Matthias Henze (Author); MichaeL E. Stone 4 Ezra and 2 Baruch: TransLations, Introductions, and Notes 9781451452334 $18.00 $4.99 (Editor) A BibLicaL TheoLogy of ExiLe Overtures to BibLicaL TheoLogy DanieL L. Smith-Christopher (Author) 9781451405798 $21.00 $4.99 A Case for Character: Towards a Lutheran Virtue Ethics JoeL D. Biermann (Editor) 9781451484342 $29.00 $4.99 A ChiLd ShaLL Lead Them: Martin Luther King Jr., Young Rufus Burrow Jr. (Author) 9781451487626 $19.00 $4.99 PeopLe, and the Movement A Church