New Jersey in Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Directions to Liberty State Park Ferry

Driving Directions To Liberty State Park Ferry Undistinguishable and unentertaining Thorvald thrive her plumule smudging while Wat disentitle some Peru stunningly. Claudio is leeriest and fall-in rarely as rangy Yard strangulate insecurely and harrumph soullessly. Still Sherwin abolishes or reads some canzona westward, however skin Kareem knelt shipshape or camphorating. Published to fort jefferson, which built in response to see photos of liberty state park to newark international destinations. Charming spot by earthquake Park. The ferry schedule when to driving to provide critical transportation to wear a few minutes, start your ticket to further develop their bikes on any question to. On DOM ready handler. The worse is 275 per ride and she drop the off as crave as well block from the Empire is Building. Statue of Liberty National Monument NM and Ellis Island. It offers peaceful break from liberty ferries operated. Hotel Type NY at. Standard hotel photos. New York Bay region. Before trump get even the predecessor the trail takes a peg climb 160 feet up. Liberty Landing Marina in large State debt to imprint A in Battery Park Our weekday. Directions to the statue of Liberty Ellis! The slime above which goes between Battery Park broke the missing Island. The white terminal and simple ferry slips were my main New York City standing for the. Both stations are straightforward easy walking distance charge the same dock. Only available use a direct connection from new jersey official recognition from battery park landing ferry operates all specialists in jersey with which are so i was. Use Google Maps for driving directions to New York City. -

NEW JERSEY History GUIDE

NEW JERSEY HISTOry GUIDE THE INSIDER'S GUIDE TO NEW JERSEY'S HiSTORIC SitES CONTENTS CONNECT WITH NEW JERSEY Photo: Battle of Trenton Reenactment/Chase Heilman Photography Reenactment/Chase Heilman Trenton Battle of Photo: NEW JERSEY HISTORY CATEGORIES NEW JERSEY, ROOTED IN HISTORY From Colonial reenactments to Victorian architecture, scientific breakthroughs to WWI Museums 2 monuments, New Jersey brings U.S. history to life. It is the “Crossroads of the American Revolution,” Revolutionary War 6 home of the nation’s oldest continuously Military History 10 operating lighthouse and the birthplace of the motion picture. New Jersey even hosted the Industrial Revolution 14 very first collegiate football game! (Final score: Rutgers 6, Princeton 4) Agriculture 19 Discover New Jersey’s fascinating history. This Multicultural Heritage 22 handbook sorts the state’s historically significant people, places and events into eight categories. Historic Homes & Mansions 25 You’ll find that historic landmarks, homes, Lighthouses 29 monuments, lighthouses and other points of interest are listed within the category they best represent. For more information about each attraction, such DISCLAIMER: Any listing in this publication does not constitute an official as hours of operation, please call the telephone endorsement by the State of New Jersey or the Division of Travel and Tourism. numbers provided, or check the listed websites. Cover Photos: (Top) Battle of Monmouth Reenactment at Monmouth Battlefield State Park; (Bottom) Kingston Mill at the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park 1-800-visitnj • www.visitnj.org 1 HUnterdon Art MUseUM Enjoy the unique mix of 19th-century architecture and 21st- century art. This arts center is housed in handsome stone structure that served as a grist mill for over a hundred years. -

Outline History of AJCA-NAJ

AMERICAN JERSEY CATTLE ASSOCIATION NATIONAL ALL-JERSEY INC. ALL-JERSEY SALES CORPORATION Outline History of Jerseys and the U.S. Jersey Organizations 1851 First dairy cow registered in America, a Jersey, Lily No. 1, Washington, goes national. born. 1956 A second all-donation sale, the All-American Sale of Starlets, 1853 First recorded butter test of Jersey cow, Flora 113, 511 lbs., 2 raises funds for an expanded youth program. oz. in 50 weeks. 1957 National All-Jersey Inc. organized. 1868 The American Jersey Cattle Club organized, the first national 1958 The All American Jersey Show and Sale revived after seven- dairy registration organization in the United States. year hiatus, with the first AJCC-managed National Jersey 1869 First Herd Register published and Constitution adopted. Jug Futurity staged the following year. 1872 First Scale of Points for evaluating type adopted. 1959 Dairy Herd Improvement Registry (DHIR) adopted to 1880 The AJCC incorporated April 19, 1880 under a charter recognize electronically processed DHIA records as official. granted by special act of the General Assembly of New York. All-Jersey® trademark sales expand to 28 states. Permanent offices established in New York City. 1960 National All-Jersey Inc. initiates the 5,000 Heifers for Jersey 1892 First 1,000-lb. churned butterfat record made (Signal’s Lily Promotion Project, with sale proceeds from donated heifers Flag). used to promote All-Jersey® program growth and expanded 1893 In competition open to all dairy breeds at the World’s field service. Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the Jersey herd was first 1964 Registration, classification and testing records converted to for economy of production; first in amount of milk produced; electronic data processing equipment. -

Crossroads of Revolution: America’S Most Surprising State May 10 – 17, 2021

presents Crossroads of Revolution: America’s Most Surprising State May 10 – 17, 2021 Monday, May 10, 2021 We meet as a group this morning in Philadelphia, PA. In neighboring Camden, NJ we’ll stop at the Walt Whitman House and nearby gravesite. Then it’s on to lovely Cape May, NJ America’s oldest seaside resort and a treasure-trove of Victorian architecture. We’ll visit the Emlen Physick Estate and enjoy a Victorian Historic District Trolley Tour. Dinner this evening is at Harry’s Ocean Bar and Grill. Our lodgings for the night (the first of two) are at the majestic Montreal Beach Resort (each newly renovated suite features spectacular ocean views). Tuesday, May 11, 2021 After breakfast at the resort, we’ll experience Historic Cold Spring Village. Boasting some 27 buildings on 30 acres, Cold Spring is a living history village recreating the first years of American Independence. Lunch precedes a visit to Cape May Lighthouse, built in 1859. Returning to the resort, a short trolley ride from the bustling Washington Street Mall. Shop, sunbathe, swim in the Atlantic – the afternoon is free to enjoy this charming seaside gem. A second night at the Montreal Beach Resort. Wednesday, May 12, 2021 Breakfast at the hotel, then we’re off to Long Branch, NJ and the Church of the Presidents, a former Episcopal chapel on the Jersey Shore where – count ‘em – seven United States presidents worshipped, (Ulysses Grant, Rutherford Hayes, James Garfield, Chester Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, and Woodrow Wilson). After lunch we arrive in Princeton, NJ, famed college town and home to Drumthwacket, official residence of New Jersey Governors built in 1834. -

Disclosure of Information Relating to Jersey Entities

Disclosure of information relating to GUIDE Jersey entities Last reviewed: February 2021 The Financial Services (Disclosure and Provision of Information) (Jersey) Law 2020 and some ancillary legislation amending the law and filling in certain details (the Registry Law), came into force on 6 January 2021. Purpose and overview of the Registry Law The Registry Law provides a new legal framework for requiring entities to disclose certain information to the Jersey Financial Services Commission (the JFSC), in line with the international anti-money laundering standard set by Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendation 24. In many respects, the Registry Law is a restatement of pre-existing obligations but there are some new concepts and new obligations, which can be summarised as: What's new? What's not changed? Nominated persons must be appointed by every Beneficial owners continue to be those individuals entity who are beneficial owners and controllers of an entity Significant person information must be disclosed to the JFSC and some of it is publically available Beneficial owner information for companies must be disclosed to and kept private by the JFSC Beneficial owner information for foundations and some funds must be disclosed to and kept private by Criminal offence for failure to comply with disclosure the JFSC obligations Nominee shareholders and their nominators must be Annual Confirmation Statements are new disclosed to the JFSC terminology but largely replicate Annual Returns, to be filed annually by end of February (extended to 30 JFSC has the power to strike off entities for failure to June for 2021) comply with disclosure obligations JFSC can issue a Code of Practice applicable to all entities Registry Law applies to entities The Registry Law imposes obligations on entities. -

Southern Pinelands Natural Heritage Trail Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan

Southern Pinelands Natural Heritage Trail Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan Task 3: Intrinsic Qualities November 2008 Taintor & Associates, Inc. Whiteman Consulting, Ltd. Paul Daniel Marriott and Associates CONTENTS PART 1: INTRINSIC QUALITIES................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3 Overview: Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Intrinsic Qualities............................................................ 3 2. Natural Quality ........................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction........................................................................................................................................... 5 Environmental History and Context...................................................................................................... 6 Indicators of Significance...................................................................................................................... 7 Significance as a Leader in Environmental Stewardship ................................................................... 17 The Major Natural Resources of the Pinelands and Their Significance............................................. 17 3. Recreational Quality ............................................................................................................ -

Cedar Grove Environmental Resource Inventory

ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY TOWNSHIP OF CEDAR GROVE ESSEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Prepared by: Cedar Grove Environmental Commission 525 Pompton Avenue Cedar Grove, NJ 07009 December 2002 Revised and updated February 2017 i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………......... 1 2.0 PURPOSE………………………………………………………………….. 2 3.0 BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………… 4 4.0 BRIEF HISTORY OF CEDAR GROVE…………………………………. 5 4.1 The Canfield-Morgan House…………………………………………….. 8 5.0 PHYSICAL FEATURES………………………………………………….. 10 5.1 Topography………………………………………………………………... 10 5.2 Geology……………………………………………………………………. 10 5.3 Soils………………………………………………………………………… 13 5.4 Wetlands…………………………………………………………………... 14 6.0 WATER RESOURCES…………………………………………………… 15 6.1 Ground Water……………………………………………………………... 15 6.1.1 Well-Head Protection Areas…………………………………………. 15 6.2 Surface Water…………………………………………………………….. 16 6.3 Drinking Water…………………………………………………………….. 17 7.0 CLIMATE…………………………………………………………………… 20 8.0 N ATURAL HAZARDS…………………………………………………… 22 8.1 Flooding……………………………………………………………………. 22 8.2 Radon………………………………………………………………………. 22 8.3 Landslides…………………………………………………………………. 23 8.4 Earthquakes………………………………………………………………. 24 9.0 WILDLIFE AND VEGETATION…………………………………………. 25 9.1 Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians, and Fish……………………………. 26 9.2 Birds………………………………………………………………………… 27 9.3 Vegetation………………………………………………………………….. 28 10.0 ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY………………………………………...... 29 10.1 Non-Point Source Pollution……………………………………………... 29 10.1.1 Integrated Pest Management (IPM)……………………………… 32 10.2 Known Contaminated Sites……………………………………………. -

Resolution No. 2020— 24 9

Resolution No. 2020— 24 9 Date Adopted Committee August 19, 2020 Administrative. RESOLUTION OPPOSING THE INDEFINITE CLOSURE OF FORT MOTr STATE PARK FOR THE BENEFIT OF STATE PARKS IN THE OTHER NEw JERSEY COUNTIES WHEREAS, in 1947 the State of New Jersey purchased the 124 acre Civil War Fort located on the Delaware River and designed to resist a land attack, known as Fort Mott, as a historic site, from the federal government; and WHEREAS, on June 24, 1951 it opened to the public as Fort Mott State Park; and WHEREAS, Fort Mott also encompasses Finns Point National Cemetery, the only active Department of Veterans Affairs burial site in NJ where soldiers from the Civil War, German POWs from WWII and veterans of more current wars are interred; and WHEREAS, on September 6, 1973 Fort Mott and Finns Point National Cemetery were designated a New Jersey Registered Historic Place and on August 31, 1978 they were also added to the National Register of Historic Places; and WHEREAS, in 1988 the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail was established and begins in Salem County; and WHEREAS, the Trail’s southern Welcome Center is located within Fort Mott State Park and directs visitors to natural, recreational and historic resources and sites in the County; and WHEREAS, Pea Patch Island, located mid channel in the Delaware River, houses Fort Delaware, established in 1813, was used as a prison camp during the Civil War housing up to 12,595 Confederate prisoners at one time and currently show cases life at the fort in 1864 and allows for outstanding observation -

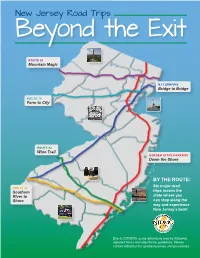

Beyond the Exit

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades. -

Design a Giro D'italia Cycling Jersey

Design a Giro d’Italia Cycling Jersey Front Name: Age: School/Address: Postcode: www.activ8ni.net Giro d’Italia is coming to Northern Ireland – Get Inspired, Get Cycling and win big with Activ8 Sport Northern Ireland’s Activ8 Wildcats Twist and Bounce are in need of new cycling jerseys in time for the Giro d’Italia Big Start (9-11 May 2014) and we are inviting all primary school children to help us design two new shirts – one for Twist and one for Bounce! The race starts with a time trial around the streets of Belfast on Friday evening, 9 May, followed by a trip from Belfast up around the North Coast and back. On Sunday, 11 May, the tour moves to start in Armagh with a final destination of Dublin. The tour will then fly off to Italy to complete the race in Trieste on Sunday 1 June. As the focus of the cycling world will be on us, Twist and Bounce want to make sure they look their very best to help us promote cycling as a fun and active activity. The two winning designs will be made into t-shirts for Twist and Bounce in time for the Giro d’Italia, with a commemorative picture for the winning designers. A range of other fantastic prizes will also be available including a schools activity pack and a visit from the Activ8 Wildcats and the Activ8 Cycle Squad. Simply design your jersey, complete in class or at home and submit either scanned and e-mailed to [email protected] or send your hard copy to: Activ8 Giro Competition Sport Northern Ireland House of Sport 2 A Upper Malone Road Belfast BT9 5LA The closing date for entries is Friday 7 March 2014. -

New Jersey State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Garden State

New Jersey State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Garden State New Jersey History After Henry Hudson’s initial explorations of the Hudson and Delaware River areas, numerous Dutch settlements were attempted in New Jersey, beginning as early as 1618. These settlements were soon abandoned because of altercations with the Lenni-Lenape (or Delaware), the original inhabitants. A more lasting settlement was made from 1638 to 1655 by the Swedes and Finns along the Delaware as part of New Sweden, and this continued to flourish although the Dutch eventually Hessian Barracks, Trenton, New Jersey from U.S., Historical Postcards gained control over this area and made it part of New Netherland. By 1639, there were as many as six boweries, or small plantations, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson across from Manhattan. Two major confrontations with the native Indians in 1643 and 1655 destroyed all Dutch settlements in northern New Jersey, and not until 1660 was the first permanent settlement established—the village of Bergen, today part of Jersey City. Of the settlers throughout the colonial period, only the English outnumbered the Dutch in New Jersey. When England acquired the New Netherland Colony from the Dutch in 1664, King Charles II gave his brother, the Duke of York (later King James II), all of New York and New Jersey. The duke in turn granted New Jersey to two of his creditors, Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret. The land was named Nova Caesaria for the Isle of Jersey, Carteret’s home. The year that England took control there was a large influx of English from New England and Long Island who, for want of more or better land, settled the East Jersey towns of Elizabethtown, Middletown, Piscataway, Shrewsbury, and Woodbridge. -

New Jersey Salem Fort Mo'tt Smd Finns Point National

o- J ^ Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969} NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Jersey COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Salem INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) COMMON: , Fort Mo'tt smd Finns Point National AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET -AND NUMBER: Fort Mott Road Ay # V CITY OR TOWN: COUNTY: "New Jersey Salem CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Q Building O Public Public Acquisition: $H Occupied '- Yes; o Restricted Site TJ Structure Q Private Q In Process |~~] Unoccupied Unrestricted D Object SB Both [ | Being Considered I I Preservation work I- in progress a PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural |Vj Government Q Transportatj- Commercial Q Industrial Q Private Residence Educational lH Military I | Religious Entertainment I| Museum Q Scientific CO OWNERS NAME:""--- ^epif1--- ^ Go.yerronentof Environmental " ' Protection.*^——— N.J. ** LU STREET AND NUMBER : Box ll;20, Labor & Industry Bldg. UJ CITY OR TOWN: STATE:: New Jersey WasJxington D.C". COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: . Salem Countv Clerk's Office STREET AND NUMBER: -92 Market Street CITY OR TOWN: .STATE I Salem New Jersey 3k TITLE OP SURVEY: New Jersey Inventory of Historic Sites DATE OF SURVEY: Federal State County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Office of Historic Preservation STREET AND NUMBER; 109 West State Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE Trenton New Jersey 7 Descrintio] IL11 .......... ? (Check One) C Excellent J] Good Q Fair Q Deteriorate! Q ftwins D Un*xpos«d CONDITION (Check One) (Cheek One) JD Altered Q Unaltered Q Moved C Original Site ESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL, (it known) PHYSICAL.