NEWSLETTER Published by the Institute for Canadian Music, Faculty of Music, University of Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Florida’S Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’S Best Community 50¢ VOL

Project1:Layout 1 6/10/2014 1:13 PM Page 1 Rays: Snell sharp as Tampa Bay wins playoff opener/B1 WEDNESDAY TODAY CITRUSCOUNTY & next morning HIGH 79 Mostly sunny, LOW breezy, cooler. 58 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOL. 125 ISSUE 358 INSIDE SPECIAL SECTION: Distinctive of the Nature City frowns on tobacco Homes Coast Crystal River council moves to further discourage smoking, vaping at facilities BUSTER olution establishing “It’s a wonderful, won- Copeland and Jim Legrone “Cigarette smoke contains THOMPSON tobacco-free zones for city derful thing that we’re going Memorial parks. more than 7,000 chemicals, Coldwell Banker Next Generation Realty – Edward Johnston – See Page 7 000Z31O Staff writer parks and recreational to do this,” Councilman Pat Inverness City Council 69 of which have been facilities. Fitzpatrick told attending passed a similar measure known to cause cancer.” Distinctive A little less cigarette Officials with the Citrus partnership members be- in June 2020. She went on to say cur- smoke and butts could be County Tobacco Free Part- fore calling the resolution “There’s no safe level rent research on Homes rising and falling at Crys- nership, a part of the Flor- to a vote. “Thank you for for secondhand smoke,” electronic-cigarette also Get a glimpse of tal River’s public venues. ida Health Department in this and I support it 100%.” Citrus County Tobacco shows aerosols emitted fabulous residences. City Council members Citrus County, proposed Signage will be posted Free Partnership Presi- from those devices contain voted 5-0 at their meeting the action to help discour- by the partnership at Yeo- dent Lorrie Van Voorthui- lead, nickel and tin. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

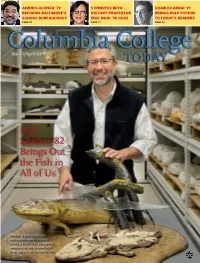

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Lecture Explores Female

C A LIFO R NI A S T A T E U NIVE RS IT Y , F U LLE R TON Jodie Cox strikes INSIDE out 16 Scarlet Knights as the 3 n NEWS: Sushi restaurants offer unique Titans begin the cuisine and community atmosphere Kia Klassic 4 n DETOUR: Nas and Jay-Z throw in their with a win. towels in the battle of lyrics —see Sports page 6 VOLU M E 73, I SSUE 14 THURSDAY M ARCH 14, 2002 Lecture explores female nSPEAKER: Artist Jacqueline Cooper presents contemporary feminist performance art Wednesday BY MICHAEL MATTER may be at CSUF but you will be negative signification of the written are still stuck trying to use exterior Daily Titan Staff Writer getting a Harvard or Scripps College word,” Cooper said. “ Arguably, a language to explain the similarities lecture.” similar spatial imperative fueled the and divisions between interior space As part of the Women’s History Cooper was born in London. She development of a performance and in both the literary and the visual Month lecture series, artist, author earned her master’s degree from installation art practice increasingly arts. and social critic Jacqueline Cooper, UCLA in 1998 and has taught at apparent since the emergence of Cooper’s opening video presenta- offered a multimedia presentation Santa Monica College and Long the women’s movement in the late tion showed three separate women titled “(Re)Presenting the Feminist Beach City College. 1960s.” sitting on stools facing the audi- Vision,” at the Titan Theatre She has also taught at UCLA and Cooper suggested that perfor- ence. -

The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Fall 10-21-2005 Volume 41 - Issue 07 - Friday, October 21, 2005 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 41 - Issue 07 - Friday, October 21, 2005" (2005). The Rose Thorn Archive. 217. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/217 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROSE-HULMAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY T ERRE HAUTE, INDIANA Friday, October 21, 2005 Volume 41, Issue 7 News Briefs Career Fair second largest ever By Alex Clerc Alex Clerc News Editor Jackson moves to n Wednesday, Oc- Bahrain tober 19, fi nding a job became a little Michael Jackson’s lawyers easier when over have confi rmed that he is now Oa hundred companies from permanently living outside of the around the country came to United States in the Arab state of recruit at Rose-Hulman. -

Broken Social Scene Lover Spit Free Mp3

Broken social scene lover spit free mp3 click here to download Lover's Spit Broken Social Scene. Now Playing. Lover's Spit. Artist: Broken Social Scene. www.doorway.ru Lover's Spit. Artist: Broken Social Scene. www.doorway.ru You can find your favorite songs in our multimillion database of best mp3 links. We provide Lover's Spit (broken Social Scene Cover Version Ii) Lamento Di. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Broken Social Scene – Lover's Spit for free. Lover's Spit appears on the album You Forgot It In People. Discover. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Broken Social Scene – Lover's Spit (Redux) for free. Lover's Spit (Redux) appears on the album The Reminder. 3 best mp3 from Arts & Crafts: Listen Snowblink — Blue Moon Arts. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Broken Social Scene – Lover's Spit for free. Buy Lover's Spit: Read 3 Digital Music Reviews - www.doorway.ru Start your day free trial. Listen to any song, Broken Social Scene Stream or buy for $ Buy Lover's Spit (Redux): Read 3 Digital Music Reviews - www.doorway.ru Start your day free trial. Listen to Broken Social Scene Stream or buy for $ All these people drinking lover's spit They sit around and clean their face with it And they listen to teeth to. Starlings flocking at Eastbourne Pier, 22/10/ Track is from 'Beehives' (), with Leslie Feist singing. Lover's Spit — Arts & Crafts: - — Broken Social Scene RedMP3. 3 best mp3 from Arts & Crafts: - Listen Snowblink — Blue Moon Arts. -

Anglo-Canadian Sheet Music and the First World War

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2016 The Sounds They Associated with War Came from Pianos, Not Guns: Anglo-Canadian Sheet Music and the First World War Wedel, Melanie Wedel, M. (2016). The Sounds They Associated with War Came from Pianos, Not Guns: Anglo-Canadian Sheet Music and the First World War (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28386 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3086 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Sounds They Associated with War Came from Pianos, Not Guns: Anglo-Canadian Sheet Music and the First World War by Melanie Lisa Wedel A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA JUNE, 2016 © Melanie Wedel 2016 Abstract The study of wartime popular sheet music produced by Anglo-Canadians is vitally important, as it illustrates what was popular in society and demonstrates how Canadians reacted to the world around them. During the First World War, the medium of patriotic sheet music catalysed the management of morale during on the home front, as it offered an emotional outlet for thousands of people in desperate need of a diversion from the grim reality and toll of the war overseas. -

Jeff Root Tedeschi Trucks Band Contact Karlo Takki

•Our 31st Year Proudly Promoting The Music Scene• FREE July 2016 Contact Jeff Root Karlo Takki Tedeschi Trucks Band Plus: Concert News, The Time Machine, Metronome Madness & more Metro•Scene ATWOOD’S TAVERN BLUE OCEAN MUSIC HALL 7/9- Marty Nestor & the BlackJacks 7/31- Steel Panther Cambridge, MA. Salisbury Beach, MA. 7/14- Bob Marley - Comedy (617) 864-2792 (978) 462-5888 7/15- Mike Zito & the Wheel 7/16- Joe Krown Trio w/ Walter “Wolfman” HOUSE OF BLUES Washington & Russell Batiste 7/1- Tim Gearan Band 7/1- Classic Vinyl Revival Show Tribute Bands: Cold Boston, MA. 7/21- The Devon Allman Band 7/2- Vapors Of Morphine As Ice, Danny Klein’s Full House, Ain’t That America (888) 693-BLUE 7/3- Pat & The Hats 7/3- Mighty Mystic; The Cornerstone 7/22- Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams 7/28- Boogie Stomp! 7/7- Dan Blakeslee & the Calabash Club 7/7- Lotus Land: A Tribute to Rush 7/1- Lulu Santos 7/8- Tim Gearan Band; Hayley Thompson-King 7/8- Mike Girard’s Big Swinging Thing 7/29- A Ton of Blues; The Mike Crandall Band 7/30- Jerry Garcia Birthday Bash w/ A Fine 7/2- Jesus Culture - Let It Echo Tour 7/9- Vapors Of Morphine 7/20- Yacht Rock Revival featuring Ambrosia, 7/6- The Smokers Club Presents: Cam’Ron, The Connection & The Not Fade Away Band 7/10- Laurie Geltman Band Player, Robbie Dupree, Matthew Wilder & The Underachievers, G Herbo & More 7/11- The Clock Burners feat. Eric Royer, Sean Yacht Rock Revue 7/7- Buchholz Benefit Bash featuring Thompson Staples, Jimmy Ryan & Dave Westner 7/14- Steve Augeri (Former Journey singer) Square 7/13- Greyhounds 7/15- The Machine CALVIN THEATER 7/12- K. -

The Weinzweig School: the Flute Works of Harry Freedman, Harry Somers, R

The Weinzweig School: The flute works of Harry Freedman, Harry Somers, R. Murray Schafer, Srul Irving Glick and Robert Aitken A Document Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2012 by Jennifer Brimson Cooper B.M., Wilfrid Laurier University, 2006 M.M., Royal Northern College of Music, 2007 Advisor: Dr. Brett Scott Readers: Dr. Matthew Peattie and Randy Bowman, B.M. ABSTRACT This document studies a generation of students of Canadian pedagogue John Jacob Weinzweig (1913-2006) who have written for the flute. R. Harry Freedman (1922-2005), Harry Somers (1925-1999), R Murray Schafer (b.1933), Srul Irving Glick (1934-2002) and Robert Aitken (b.1939) have all contributed substantial works to the canon of Canadian flute repertory. The purpose of this document is to show the artistic aims and scope of these composer’s works, exploring their respective approaches to writing for the flute. By synthesizing analytic and aesthetic approaches to composition and through the study of available literary history and criticism this document will broaden the perspective on Canadian flute literature. Pieces to be examined in detail include: Harry Freedman, Soliloquy (1971); Harry Somers, Etching from the Vollard Suite (1964); R. Murray Schafer, Sonatina (1958); Srul Irving Glick, Sonata for Flute and Piano (1983) and Robert Aitken, Icicle (1977). BLANK PAGE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge Dr. Brett Scott for his help with the generation of the document proposal and for his guidance through the writing and editing stages of this document, and the members of my committee, Dr. -

Matthew Capel Thesis 18 September 2007

'Damned If They Do And Damned If They Don't': The Inferiority Complex, Nationalism, and Maclean's Music Coverage, 1967-1995 By Gordon Matthew Donald Capel A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2007 © Gordon Matthew Donald Capel 2007 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as required by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This thesis critically analyses music coverage in Maclean’s between 1967-1995, and reveals that the magazine continually stressed Canadian music as inferior to that produced by foreign artists. Only during times of intense nationalism were Canadian musicians positively received in its pages. More generally, domestic productions were seen as deficient. The historical components of this investigation reveal an essential irony in the perception of Canadian music during the last four decades of the 20th century. Despite nationalist rhetorics and Maclean's self-appointed title of "Canada's National Newsmagazine," its critics consistently emphasised that Canadian music was of poor quality in the 1967-1995 period. iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to all those wonderful people who helped me complete this thesis. First, I must applaud my thesis advisor P. Whitney Lackenbauer for his motivation, discerning eye, and willingness to tell me when something wasn't history. For this confused, stubborn, and excitable grad student, your support cannot be overstated. -

Have Not Been the Same: the Canrock Renaissance, 1985-1995

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 05:30 Ethnologies Have Not Been The Same: The CanRock Renaissance, 1985-1995. By Michael Barclay, Ian A. D. Jack and Jason Schneider. (Toronto: ECW Press, 2001. Pp. vii + 757, annotated table of contents, black/white and colour photographs, selected critical discography, interview schedule, bibliography, cast of characters, index, ISBN 1-55022-475-1, pbk.) Dufferin A. Murray Language and Culture / Langue et culture Volume 25, numéro 2, 2003 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/008057ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/008057ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Association Canadienne d'Ethnologie et de Folklore ISSN 1481-5974 (imprimé) 1708-0401 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Murray, D. A. (2003). Compte rendu de [Have Not Been The Same: The CanRock Renaissance, 1985-1995. By Michael Barclay, Ian A. D. Jack and Jason Schneider. (Toronto: ECW Press, 2001. Pp. vii + 757, annotated table of contents, black/white and colour photographs, selected critical discography, interview schedule, bibliography, cast of characters, index, ISBN 1-55022-475-1, pbk.)]. Ethnologies, 25(2), 238–242. https://doi.org/10.7202/008057ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2003 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal.