Grant Morrison” and Grantmorrison™

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANTIQUE BOOKSHOP CATALOGUE 344 the Antique Bookshop & Curios

ANTIQUE BOOKSHOP CATALOGUE 344 The Antique Bookshop & Curios Phone Orders To: (02) 9966 9925 Fax Orders to: (02) 9966 9926 Mail Orders to: PO Box 7127, McMahons Point, NSW 2060 Email Orders to: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.antiquebookshop.com.au Books Held At: Level 1, 328 Pacific Highway, Crows Nest 2065 All items offered at Australian Dollar prices subject to prior FOREWORD We seem to be a community in fear at the moment. Real fear of con- sale. Prices include GST. Postage & insurance is extra. tracting Covid 19 but irrational fear of running out of paper products, Payment is due on receipt of books. namely toilet paper, paper towels and boxes of tissues. To say nothing No reply means item sold prior to receipt of your order. or pasta and rice. I’ve managed to purchase enough of these products, buying just what Unless to firm order, books will only be held for three days. I needed each time. There is no real shortage; as the paper products are made in Australia. Perhaps having a large reserve of toilet paper reduces the fear of Covid 19 for the irrational amongst us. CONTENTS There are alternatives to toilet paper. I remember being in the bush as BOOKS OF THE MONTH 1 - 30 a lad and the dunny in the back yard usually had the local newspaper nailed to the back of the door for this purpose. AUSTRALIA & THE PACIFIC 31 - 226 A leading antiquarian bookdealer (sorry, no names) visiting my MISCELLANEOUS 227 - 369 premises many years ago, and finding we had run out of loo paper used the pages of an derelict old dictionary from one of the boxes of books stacked in the bath in the bathroom. -

SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE PRESENTS a Festival Celebrating the Art Of

SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE PRESENTS A festival celebrating the art of graphic storytelling, illustration, comics, animation and music MONDAY 28 SEPTEMBER, SATURDAY 10 & SUNDAY 11 OCTOBER SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE A festival of graphic storytelling, animation and music featuring: Mad Max: Fury Road - Creating the Apocalypse - George Miller, Brendan McCarthy and Nico Lathouris in conversation; Kevin Smith's Superhero Multiverse with special guest Jason Mewes; Sarah Blasko - Eternal Return Album Preview with Commissioned Visuals by Mike Daly; Ólafur Arnalds + visuals by Máni Sigfússon with 13-piece chamber orchestra and new arrangements by Viktor Orri Árnason; The Walking Dead: Season 6 Premiere – FREE SCREENING FREE TALKS from Brendan McCarthy, Nicola Scott, Animal Logic, Brendan Fletcher, Simon Rippingale and Erica Harrison; FREE SCREENINGS of Warren Ellis’ Captured Ghosts, The Mindscape of Alan Moore, She Makes Comics and Future Shock! 2000 AD; A Cautionary Tail and Oscar Wilde’s The Nightingale & The Rose “The smartest, wisest, most cutting edge festival and celebration of narrative literature and its intersection with culture in the world.” NEIL GAIMAN The Sydney Opera House today announced the program for the fifth GRAPHIC festival, taking place on Monday 28 September and Saturday 10 – Sunday 11 October. Featuring the exclusive commissions, world and Australian premieres that the festival has become synonymous with, this year GRAPHIC will also host ten free film screenings and talks from the most exciting storytellers in print, pixel and pop, on the stages and foyers of the Sydney Opera House. GRAPHIC co-curator and Sydney Opera House Head of Contemporary Music Ben Marshall said, “Sydney Opera House presents Graphic in order to celebrate the high artistic beats in forms of modern storytelling that are often ignored in traditional arts conversations and yet are capable of greatness. -

{PDF EPUB} Stargirl by Geoff Johns Geoff Johns

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Stargirl by Geoff Johns Geoff Johns. Geoff Johns (born January 25, 1973) is an American comic book writer, screenwriter, director, and producer. In June 2018, he stepped down from the position of Chief Creative Officer (CCO) of DC Entertainment to focus on producing and writing. Contents. Career. Stargirl Comics. Geoff was close to his sister, Courtney who died in 1996 due to the TWA flight 800 disaster. She was eighteen at the time and was on her way to France to be a foreign exchange student. Three years later in 1999, Geoff sold his first comic book proposal to DC Comics. He called it, "Stars and S.T.R.I.P.E.". It starred Courtney Whitmore, the second Star-Spangled Kid, later known as Stargirl, alongside S.T.R.I.P.E.. It was a story about how a family is created by bond, not blood. Stargirl was named after and inspired by his sister, Courtney. It is her spirit and optimistic energy that he wanted to put back in the world with Stargirl . Creating Stargirl TV Series. In July 2018, Geoff Johns announced a Stargirl series, where he, along with Greg Berlanti and Sarah Schechter, would pen and executive produce the show for the OTT DC Universe service. [1] For casting, he wrote the role of Pat Dugan specifically for Luke Wilson, and mailed him a copy of the script along with a personal letter. They spoke about the role and Luke eventually signed onto the project. After landing Brec Bassinger as the titular character Courtney Whitmore, he sat down and spoke with her for hours on his plans for Courtney and the series. -

The Multiversity by Grant Morrison

The Multiversity by Grant Morrison Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited books*. Accessible on all your screens. Ebook The Multiversity available for review only, if you need complete ebook "The Multiversity" please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >>> *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every book is in the library. You can choose FREE Trial service and download "The Multiversity" ebook for free. Ebook Details: Review: Grant Morrison has been hit or miss with me, and after finishing The Multiversity I think Ive finally cracked his code. To me, Grant Morrison is at his best when not working directly on one character (i.e. his Batman run) but one grand epic scale that doesnt necessarily fall into character continuity. The Multiversity is everything Ive heard people... Original title: The Multiversity Paperback: 448 pages Publisher: DC Comics (November 22, 2016) Language: English ISBN-10: 1401265251 ISBN-13: 978-1401265250 Product Dimensions:6.6 x 0.7 x 10.2 inches File Format: pdf File Size: 18385 kB Ebook File Tags: grant morrison pdf,final crisis pdf,pax americana pdf,society of super-heroes pdf,seven soldiers pdf,jim lee pdf,alan moore pdf,justice league pdf,deluxe edition pdf,ultra comics pdf,crisis on infinite pdf,single issues pdf,fourth wall pdf,freedom fighters pdf,red son pdf,across the multiverse pdf,single issue pdf,alternate realities pdf,captain marvel pdf,make sense Description: GRANT MORRISONS #1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLERThe biggest adventure in DCs history is here! Join visionary writer Grant Morrison, todays most talented artists, and a cast of unforgettable heroes from 52 alternative Earths of the DC Multiverse! Prepare to meet the Vampire League of Earth-43, the Justice Riders of Earth-18, Superdemon, Doc Fate, the.. -

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975044 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $12.99/$14.99 Can. cofounders Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley, Archie 112 pages expects this title to be a breakout success. Paperback / softback / Trade paperback (US) Comics & Graphic Novels / Fantasy From the the company that’s sold over 1 billion comic books Ctn Qty: 0 and the band that’s sold over 100 million albums and DVDs 0.8lb Wt comes this monumental crossover hit! Immortal rock icons 363g Wt KISS join forces ... Author Bio: Alex Segura is a comic book writer, novelist and musician. Alex has worked in comics for over a decade. Before coming to Archie, Alex served as Publicity Manager at DC Comics. Alex has also worked at Wizard Magazine, The Miami Herald, Newsarama.com and various other outlets and websites. Author Residence: New York, NY Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS: Collector's Edition Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent, Gene Simmons fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975143 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $29.99/$34.00 Can. -

Nou3:L'humain,Lecyborg Et Les Espèces

NOU3 : L’HUMAIN, LE CYBORG ET LES ESPÈCES COMPAGNES Par Bruno Thomé Et si Médor et Pupuce devenaient des armes de destruction massive ? C’est ce que le tandem écossais Morrison/Quitely a imaginé pour son one shot comic book : Nou3, pur shoot stroboscopique de gore à fourrure. Histoire de réaliser une bonne fois pour toute que la guerre « zéro mort » n’existe que dans l’imagination des responsables de com’ en kaki. Un dictateur en short et ses gardes du corps se font mas- réalistes, que dans la subtile exagération de certaines pos- sacrer dans une somptueuse villa. Trois masses de métal tures ou expressions faciales, telles les poses culturistes de surgissent de la maison juste avant son explosion, puis re- Flex Mentallo avec son slip léopard et son torse difforme et gagnent la remorque d’un camion garé devant. Dans le ca- velu, directement inspirées des réclames pour la méthode mion portant l’inscription « Animalerie », des hommes en- de développement musculaire du professeur Charles At- lèvent leurs trois casques, découvrant un chien, un chat, las des vieux comics. Son trait méticuleux évoque parfois et un lapin. Ce sont en fait des biorgs, animaux chirur- le regretté Moebius, par cette sorte de puissance douce, gicalement et génétiquement modifiés par l’US Air Force de mélancolie souriante, que dégagent certains de ses des- pour piloter des armures de combats. « 3 », le lapin, libère sins. Ainsi de son Superman All-star tout en décontrac- des gaz létaux et pose des mines comme autant de petites tion, rayonnant de force, qui s’inspire de la posture tran- crottes ; « 2 », le chat, est un combattant furtif des plus fa- quille d’un fan déguisé en Kryptonnien, et tranche radi- tals, et « 1 », le chien, est un véritable petit tank. -

English Digest the Magazine Helping Students Learn English Modern English Publishing

p01-21 11/8/05 5:33 PM Page 1 MODERN ENGLISH DIGEST THE MAGAZINE HELPING STUDENTS LEARN ENGLISH MODERN ENGLISH PUBLISHING Mountain Bikes Eco-tourism The World’s Most Famous Painting Plus: Diamonds Collecting Lighthouses Old Comics Edinburgh’s Royal Mile Vol 3 / Issue 4 £4.25 Vol Zhang Ziyi p01-21 10/8/05 10:33 AM Page 2 e have packed this latest issue of Modern English Digest with a wide range of features that will make learning English interesting and fun! All the articles in this magazine are carefully written in graded English to cater W for elementary and intermediate level students of English. Macmillan Education is delighted to announce a partnership with Modern English Digest magazine. Each issue will feature an extract from our award- winning series of simplified readers. The magazine has a great mix of interesting articles that help improve vocabulary and understanding in cultural and work-specific context. We very much hope that you find the articles useful and relevant to your studies – please write in if you have any comments or visit our website, www.ModernEnglishDigest.com, for the latest news. Your guide to the graded English used in Modern English Digest Elementary E • Simple passive forms • Comparative and superlative of adjectives • Infinitives of purpose: to, in order to • Reported commands in the past • Modals – could (ability), can (permission) • Adverbs of frequency and manner • Present perfect • Constructions with it and until • -ing verb form after like, enjoy • Indefinite pronouns: everyone, everybody, etc. • be -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10. -

Doom Patrol Vol. 2: Nada by Gerard Way

Doom Patrol Vol. 2: Nada by Gerard Way Ebook Doom Patrol Vol. 2: Nada currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Doom Patrol Vol. 2: Nada please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: Doom Patrol (Book 2)+++Paperback:::: 168 pages+++Publisher:::: DC Comics (December 24, 2018)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1401275001+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1401275006+++Product Dimensions::::5.9 x 0.9 x 8.3 inches++++++ ISBN10 1401275001 ISBN13 978-1401275 Download here >> Description: Gerard Ways Young Animal flagship title continues its monumental run here with DOOM PATROL VOL. 2!Flex Mentallo, Robotman, Rebis, Crazy Jane and more are back to twist minds and take control. The most prevailing question in Vol. 2? What is S**t, and why is everyone eating it? Cliff doesnt like it, but Casey cant get enough. Sure, Cliff doesnt like a lot of stuff, but that doesnt mean hes wrong to be suspicious this time around. Meanwhile, we find out where Lotion the cat got off to, and how his journey has changed him. Life on the streets has made him an entirely different animal!The spirit of Grant Morrisons groundbreaking DOOM PATROL is captured in this debut series starring the cult-favorite misfits as a part of Gerard Ways new Young Animal imprint. Collects issues #7-12.DOOM PATROL is the flagship title of Young Animal--a four-book grassroots mature reader imprint, creatively spearheaded by Gerard Way, bridging the gap between the DCU and Vertigo, and focusing on the juxtaposition between visual and thematic storytelling. -

Comic Annuals for Christmas

Christmas annuals: They were once as much a part of the festive celebration as turkey and the trimmings. Steve Snelling recalls Christmases past with comic immortals like Alf Tupper, Robot Archie and Lonely Larry Comic season’s greetings from all my heroes ostalgia’s a funny thing. I like to But, thankfully, such illusions would remain think of it as a feelgood trick of the unshattered for a little longer and, though I memory where all pain and didn’t know it then, that less than surprising discomfort is miraculously excised gift from a most un-grotto-like publishing and the mind’s-eye images are house on the edge of Fleet Street marked the forever rose-tinted. And while it may beginning of a Christmas love affair with the not always be healthy to spend too much time comic annual that even now shows precious Nliving in the past, I doubt I’m alone in finding it little sign of waning. strangely comforting to occasionally retreat Of course, much has changed since that down my own private Christmas morning when I tore open the memory lane. festive wrapping to reveal the first-ever Christmas is a case in Victor Book for Boys, its action-packed cover point. No matter how hard featuring a fearsome-looking bunch of Tommy- I might try, nothing quite gun wielding Commandos pouring from the measures up to visions of battered bows of the destroyer Campbeltown festive times past when to moments after it had smashed into the dock revel in the beguiling magic gates of St Nazaire. -

!["/Title/Tt3702160/": {"Director": [["Kimberly Jessy"]], "Plot": ["\Nbeautiful D Anger Is an Animated 3D Made for TV/Short Film](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9886/title-tt3702160-director-kimberly-jessy-plot-nbeautiful-d-anger-is-an-animated-3d-made-for-tv-short-film-1179886.webp)

"/Title/Tt3702160/": {"Director": [["Kimberly Jessy"]], "Plot": ["\Nbeautiful D Anger Is an Animated 3D Made for TV/Short Film

{"/title/tt3702160/": {"director": [["Kimberly Jessy"]], "plot": ["\nBeautiful D anger is an Animated 3D Made for TV/Short Film. It's a Thriller that combines, M TV's Teen Wolf, Pretty Little Liars, Gossip Girl, Sorcery, Twilight, in one film , Epic fight scenes, No-one is who you think they are, Alternate Universes, Teen Young Adult Action Good Verses Evil, flick with tons of Cliff Hangers! It takes place In Dark Oak, CA were the typical mean girl with magical powers tries to t ake over the school with her mean girl clique. Brooke Charles Takes on Kimberly Jesika and her good girl team. Death Becomes Brook cause she keeps coming back, Think Katherine Vampire Diaries. Kimberly has magical powers and so does her cla n. It's a match to the death. No one is who they seem or who they appear to be! Excitement and sitting on the edge of your seat. Written by\nKimb erly Jessy "], "imdb_rating": [], "mpaa_rating": [], "poster_link": [], "stars": [["Kimberly Jessy"], ["Helena Evans"], ["Chloe Benoit"]], "title": "Beautiful D anger 3D Animated Teen Thriller", "genre": [[" Animation"]], "release_date": [], "writer": [["Kimberly Jesika"], ["Doll Face Animated Films"]]}, "/title/tt25692 02/": {"director": [["Emily Gossett"]], "plot": ["\nThe last year of high school has been barely tolerable for Maggie Masters. After being dumped by her three y ear relationship with Chad, to be traded in for a football dream at UF, she has to succumb to her mother leaving for a better life. Maggie is left to pick up th e remains of her fragmented life. When fate intervenes by the touch from the mys terious and handsome Caleb Jacobson, whom she saves, leaves Maggie breathless, s tartled and captivated. -

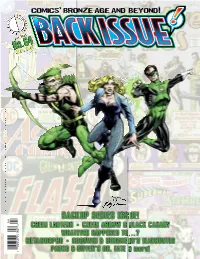

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard .