Policy Challenges of Cross-Border Cloud Computing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

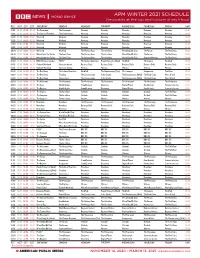

APM WINTER 2021 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the Top and Bottom of Each Hour

APM WINTER 2021 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the top and bottom of each hour PST MST CST EST SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:00 21:30 22:30 23:30 00:30 The Cultural Frontline The Conversation Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:30 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:00 22:30 23:30 00:30 01:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:30 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:00 23:30 00:30 01:30 02:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:30 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Weekend Weekend The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 08:00 00:30 01:30 02:30 03:30 When Katty Met Carlos The Food Chain The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 08:30 00:50 01:50 02:50 03:50 When Katty Met Carlos The Food Chain The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club Sporting Witness The Real Story 08:50 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 BBC OS Conversations FOOC* The Climate Question People Fixing the World HardTalk The Inquiry HardTalk 09:00 01:30 02:30 03:30 04:30 Outlook Weekend Science in Action Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 09:30 01:50 02:50 03:50 04:50 Outlook Weekend Science in Action Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 09:50 02:00 03:00 04:00 05:00 The Real Story The Cultural Frontline HardTalk The Documentary -

Digital Planet 2017 How Competitiveness and Trust in Digital Economies Vary Across the World

DIGITAL PLANET 2017 HOW COMPETITIVENESS AND TRUST IN DIGITAL ECONOMIES VARY ACROSS THE WORLD Bhaskar Chakravorti and Ravi Shankar Chaturvedi The Fletcher School, Tufts University July 2017 WELCOME SPONSOR DATA PARTNERS OTHER DATA SOURCES CIGI-IPSOS GSMA Wikimedia Edelman ILO World Bank Euromonitor ITU World Economic Forum Freedom House Numbeo World Values Survey Google Web Index DIGITAL PLANET 2017 HOW COMPETITIVENESS AND TRUST IN DIGITAL ECONOMIES VARY ACROSS THE WORLD 2 WELCOME AUTHORS DR. BHASKAR CHAKRAVORTI Principal Investigator The Senior Associate Dean of International Business and Finance at The Fletcher School, Dr. Bhaskar Chakravorti is also the founding Executive Director of Fletcher’s Institute for Business in the Global Context (IBGC) and a Professor of Practice in International Business. Dean Chakravorti has extensive experience in academia, strategy consulting, and high-tech R&D. Prior to Fletcher, Dean Chakravorti was a Partner at McKinsey & Company and a Distinguished Scholar at MIT’s Legatum Center for Development and Entrepreneurship. He has also served on the faculty of the Harvard Business School and the Harvard University Center for the Environment. He serves on the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Innovation and Entrepreneurship and the Advisory Board for the UNDP’s International Center for the Private Sector in Development, is a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution India and the Senior Advisor for Digital Inclusion at The Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth. Chakravorti’s book, The Slow Pace of Fast Change: Bringing Innovations to Market in a Connected World, Harvard Business School Press; 2003, was rated one of the best business books of the year by multiple publications and was an Amazon.com best seller on innovation. -

Morrie Gelman Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8959p15 No online items Morrie Gelman papers, ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Finding aid prepared by Jennie Myers, Sarah Sherman, and Norma Vega with assistance from Julie Graham, 2005-2006; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Morrie Gelman papers, ca. PASC 292 1 1970s-ca. 1996 Title: Morrie Gelman papers Collection number: PASC 292 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 80.0 linear ft.(173 boxes and 2 flat boxes ) Date (inclusive): ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Abstract: Morrie Gelman worked as a reporter and editor for over 40 years for companies including the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Post, Newsday, Broadcasting (now Broadcasting & Cable) magazine, Madison Avenue, Advertising Age, Electronic Media (now TV Week), and Daily Variety. The collection consists of writings, research files, and promotional and publicity material related to Gelman's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Gelman, Morrie Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

4 December 2020 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2020 Already Set up and Ready for Business

World Service Listings for 28 November – 4 December 2020 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2020 already set up and ready for business. BBC Thai's Chaiyot SAT 06:06 Weekend (w172x7d5fr78h9f) Yongcharoenchai set out to crack the mystery of the self-styled Iranian nuclear scientist killed SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5p5kcw9djy) "CIA" food hawkers. The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. Iran has urged the United Nations to condemn the assassination ‘They messed with the wrong generation’ of its top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, and it's Peru has been in the headlines for having three presidents in a pointed the finger at Israel. We explore how the incoming SAT 00:06 The Real Story (w3cszcnx) week. It’s a story of corruption allegations, impeachment and Biden administration's relationship with its traditional ally will Covid vaccines: An opportunity for science? mass protests, with young people saying their generation has shape regional tensions. had enough of the broken system which their parents put up The rapid development of coronavirus vaccines has heightened with. Ana Maria Roura has been making sense of events for Also on the programme: The number of confirmed coronavirus the hope for a world free of Covid-19. Governments have BBC Mundo. cases in the United States has passed thirteen million, with the ordered millions of doses, health care systems are prioritising pandemic still surging from coast to coast; And a new recipients, and businesses are drawing up post-pandemic plans. Lahore's toxic smog documentary explores Frank Zappa the man, his music, and But despite these positive signs, many people still feel a sense It's the time of year when many Pakistani rice farmers set fire politics. -

World Service Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 Arabic’S Ahmed Rouaba, Who’S from Algeria, Explains Why This with Their Heritage

World Service Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 Arabic’s Ahmed Rouaba, who’s from Algeria, explains why this with their heritage. cannon still means so much today. SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5p7cqg64l4) To comment on these stories and others we are joined on the The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. Remedies for the morning after programme by Emma Bullimore, a British journalist and Before coronavirus concerns in many countries, this was the broadcaster specialising in the arts, television and entertainment time of year for parties. But what’s the advice for the morning and Justin Quirk, a British writer, journalist and culture critic. SAT 00:06 BBC Correspondents' Look Ahead (w3ct1cyx) after, if you partied a little too hard? We consult Oleg Boldyrev BBC correspondents' look ahead of BBC Russian, Suping of BBC Chinese, Brazilian Fernando (Photo : Indian health workers prepare for mass vaccination Duarte and Sharon Machira of BBC Nairobi for their local drive; Credit: EPA/RAJAT GUPTA) There were times in 2020 when the world felt like an out of hangover cures. control carousel and we could all have been forgiven for just wanting to get off and to wait for normality to return. Image: Congolese house at the shoreline of Congo river SAT 07:00 BBC News (w172x5p7cqg6zt1) Credit: guenterguni/Getty Images The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. But will 2021 be any less dramatic? Joe Biden will be inaugurated in January but will Donald Trump have left the White House -

Anti-Wi-Fi Paint Offers Security

Low graphics Help Search Explore the BBC ONE-MINUTE WORLD NEWS Page last updated at 11:59 GMT, Wednesday, 30 September 2009 12:59 UK News Front Page E-mail this to a friend Printable version Anti-wi-fi paint offers security Africa DIGITAL PLANET SEE ALSO Americas By Dave Lee Teacher switches off class wi-fi Asia-Pacific BBC World Service 25 Sep 09 | Northern Ireland Europe Researchers say they have 'Next generation' wi-fi approved Middle East created a special kind of paint 14 Sep 09 | Technology which can block out wireless South Asia NY cafes crack down on free wi-fi signals. 14 Aug 09 | Technology UK Business It means security-conscious RELATED INTERNET LINKS Health wireless users could block their Shin-ichi Ohkoshi Science & Environment neighbours from being able to The BBC is not responsible for the content of external access their home network - internet sites Technology without having to set up Entertainment encryption. TOP TECHNOLOGY STORIES Also in the news ----------------- The paint contains an aluminium- Microsoft bets on Windows success Video and Audio iron oxide which resonates at the EU warns Oracle over Sun takeover ----------------- same frequency as wi-fi - or other Government opens data to public Programmes radio waves - meaning the | News feeds Have Your Say airborne data is absorbed and In Pictures blocked. With a quick lick of paint, your wi-fi Country Profiles connection could be secured By coating an entire room, signals MOST POPULAR STORIES NOW Special Reports can't get in and, crucially, can't get out. SHARED READ WATCHED/LISTENED Related BBC sites Developed at the University of Tokyo, the paint could cost as little as Sport Leaping wolf snatches photo prize £10 per kilogram, researchers say. -

Info7 2017-2 S-48-51

48 AUS WISSENSCHAFT UND FORSCHUNG info7 2|2017 Von »Old Media« zum interaktiven Radio? Julia Lorke Man startet gemeinsam in den Tag, sobald der Ra dio- Charakter zu bewahren. Es scheint also häufig so, als wecker klingelt, man liest gemeinsam Zeitung und würde man als Hörer tatsächlich Zeit mit den Mode- fährt gemeinsam zur Arbeit. Spätestens zur Rush ra toren der Radiosendung verbringen. Aller dings Hour trifft man sich im Auto wieder, kocht gemein- scheint die Kommunikation hier eher unidirektional sam, geht zu Bett und ist am nächsten Morgen, wenn zu sein, und das ist eine eher wenig attraktive Kom- der Wecker klingelt, wieder vereint. Die Rede ist hier munikationsform in zwischenmenschlichen Bezieh- nicht von zwischenmenschlichen Beziehun gen son- un gen. Dank des technologischen Fort schritts sind dern es geht um die Beziehung zwischen dem Radio jedoch auch im Bereich von Radio und seinem Pub- und seinen Hörern. Radio wird nicht umsonst als likum vielfältige Kommu nika tions for men möglich. Dr. Julia Lorke Imperial College „the intimate medium“ bezeichnet, denn Radio be- Nach Tiziano Bonini lässt sich die historische Ent- London gleitet uns in Alltagssituationen, sogar solche, die wir wicklung der Beziehung des Mediums Radio zu sei- MSc Science Communication sonst nur mit unserem Partner oder unserer Familie nem Publikum in vier Phasen einteilen (siehe Tabelle 1). South Kensington verbringen. Aber selbst wenn wir ganz alleine Radio Diese Phasen zeigen deutlich, wie technologi- Campus - oder natürlich Podcasts – hören werden wir meist sche Entwicklungen dazu beigetragen haben, dass London SW7 2AZ +49 2821 8067 39730 direkt angesprochen von den Moderatoren. -

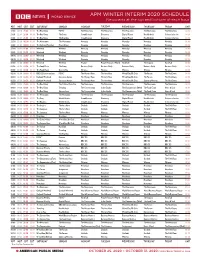

2020 BBC Fall Schedule

APM WINTER INTERIM 2020 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the top and bottom of each hour PDT MDT CDT EDT SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 The Real Story FOOC* The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom 04:00 21:30 22:30 23:30 00:30 The Real Story The Story CrowdScience Discovery Digital Planet Healthcheck Science in Action 04:30 21:50 22:50 23:50 00:50 The Real Story The Big Idea CrowdScience Discovery Digital Planet Healthcheck Science in Action 04:50 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:00 22:30 23:30 00:30 01:30 The Cultural Frontline Heart & Soul Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:30 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:00 23:30 00:30 01:30 02:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:30 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:00 00:30 01:30 02:30 03:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:30 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 Weekend Weekend Feature People Fixing the World HardTalk The Inquiry HardTalk 08:00 01:30 02:30 03:30 04:30 The Food Chain The Story Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 08:30 01:50 02:50 03:50 04:50 The Food Chain Over to You Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 08:50 02:00 03:00 04:00 05:00 BBC OS Conversations FOOC* The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 09:00 02:30 03:30 04:30 05:30 Outlook -

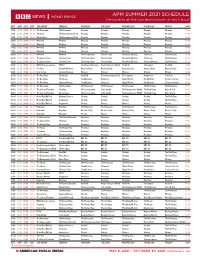

APM SUMMER 2021 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the Top and Bottom of Each Hour

APM SUMMER 2021 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the top and bottom of each hour PDT MDT CDT EDT SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 04:00 21:30 22:30 23:30 00:30 Trending The Documentary (Tue) Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 04:30 21:50 22:50 23:50 00:50 More or Less The Documentary (Tue) Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 04:50 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:00 22:30 23:30 00:30 01:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:30 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:00 23:30 00:30 01:30 02:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:30 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Weekend Weekend The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 07:00 00:30 01:30 02:30 03:30 The Conversation The Food Chain The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 07:30 00:50 01:50 02:50 03:50 The Conversation The Food Chain The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club Sporting Witness The Real Story 07:50 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 BBC OS Conversations FOOC* The Climate Question People Fixing the World HardTalk The Inquiry HardTalk 08:00 01:30 02:30 03:30 04:30 The Story Outlook Weekend Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 08:30 01:50 02:50 03:50 04:50 Over to You Outlook Weekend Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 08:50 02:00 03:00 -

Gazette Volume 22, No

GAZETTE Volume 22, No. 3 • January 21, 2011 • A weekly publication for Library staff Jefferson Draws Record Number Of Visitors By Mark Hartsell A record number of visitors entered the Thomas Jefferson Building in the last fiscal year to see exhibitions, attend concerts, use the reading rooms or just take in the splendor of the 19th-century building. According to figures released this month, more than 1.03 million people vis- ited the Jefferson Building from October 2009 to September 2010 – an increase of ALA president Roberta Stevens (fifth from left) with colleagues at a California Library more than 7 percent over the previous Association conference in Sacramento in November. fiscal year. The Jefferson drew a greater number of visitors despite the heavy snows last For Stevens, ALA Presidency winter that paralyzed the region and shut down the Library of Congress for seven Means a Road More Traveled days in February 2010 and two days in in the Netherlands, from the pages of December 2009. By Mark Hartsell Newsweek to the airwaves of XM Sirius, The number of visitors to all three from a gathering at Lake of the Ozarks Library buildings combined dropped to a Banned Books Week Read-out at slightly, declining 1.9 percent from fiscal oberta Stevens didn’t realize quite Lake Michigan. year 2009. The Library recorded 1.7 mil- what she was getting into when she She has taken more than 15 such lion visits in the recently completed fiscal R took a leave of absence from the trips since entering office, and the pace year, down from 1.73 million. -

Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday

UK GMT + 1 A GUIDE TO LISTENING IN ENGLISH including England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales MARCH – OCTOBER 2021 Where you see this sign v you will hear a short News Update at 30 minutes past the hour GMT SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 0:00 News News News News News News News 0:00 0:06 Business Matters v The Science Hour v World Business Report v Business Matters v Business Matters v Business Matters v Business Matters v 0:06 0:32 Discovery (rpt) 0:32 1:00 The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v 1:00 1:32 Stumped When Katty Met Carlos The Climate Question The Documentary (Tue) The Compass Assignment World Football 1:32 2:00 News News News News News News News 2:00 2:06 The Fifth Floor v Weekend Documentary/ Weekend Feature v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v 2:06 2:32 Book Club v The Story 2:32 2:50 Witness Over To You Witness Witness Witness Witness 2:50 3:00 News News The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v The Newsroom v 3:00 3:06 The Real Story (rpt) v FOOC v 3:06 3:32 The Cultural Frontline The Conversation In The Studio The Documentary (Wed) The Food Chain Heart & Soul 3:32 4:00 The Newsroom v The Newsroom v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v 4:00 4:32 Trending The Documentary (Tue) 4:32 4:50 Ros Atkins On… (rpt) 4:50 5:00 Weekend v Weekend v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v 5:00 6:00 Weekend v Weekend v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v Newsday v 6:00 7:00 Weekend v Weekend -

Sierra Leone Agenda

PROPOSED PROGRAMME DRAFT PROGRAMME : TRAINING COURSE ON BUDGET AND FINANCIAL REPORTING. February 19 th – 22 nd , 2008. Freetown, Sierra Leone. Orin Gordon, Course Co-coordinator. Date and Time Topic Facilitator Day One, Wednesday 20 February 9.00 - 10.30 • Registration Participants • Welcome remarks and introduction Mr.Alpha A.Jalloh Programme Director, CPD • Statement by Comsec Rep? • Keynote Address Alhaji Ibrahim Ben Kargbo Minister of Information • Overview of the workshop and Orin Gordon objectives Course Co-ordinator 10-30 - 11.0 Tea/Coffee Break 11.00 - 12.00 • Participants' introductions • Interactive Q and A discussion session on budget reporting: Course coord. & local editor 12.00 - 12.30 National experience - local journalists Course coord. & local editor 12.30 - 1.00 An introduction to corporate reporting Professor Anya Schiffrin and covering the stock market 1.00 - 2.00 Lunch Break 2.00 - 2.45 Hypotheticals (short post lunch session): Orin Gordon. Discussion of dilemmas, decisions faced by budget reporters under deadline constraints. 2.45 - 3.15 Media's Oversight Role Examples from Paul Busharizi Uganda 3.15 - 3.45 Budget Document: Politics, process and Mr.Mathew Dingie, Director of delivery Budget in the Ministry of Finance 3.45 - 4.00 Tea Break 4.00 – 5.00 • Role of the Auditor General Mr Leslie Sylvester Deputy Auditor General • Role of Public Procurement in the Mr Alfred H Kandeh budgetary process - Chief Executive Officer Public Procurement Authority 5.00- 5.45 Stories from Day 1 summary and Look Orin Gordon Head 1 Day 2, Thursday 21 February 8.45 - 9.00 Introduction to Day 2 Orin Gordon 9.00 – 10.00 Jargon: Understanding and Reporting Orin Gordon Financial and Economic terms 10.00 - 10.30 Regional Experiences - journalists from Lloyd Evans, Ghana Ghana, Nigeria and Uganda Paul Bushariz, Nigeria Nik Ogubulie, Nigeria 10.30 - 10.45 Tea/coffee break 10.45 – 12.00 Role of the Press in resource-rich Prof Anya Schiffrin countries 12.00 - 1.00 Statistics, Facts and Figures: Breaking Paul Busharizi and Orin Gordon.