Clapper Rail Summer 2018 Editor's Note Inside This Issue 3 Plumb Beach 7 Nests Clapper Rail at Plumb Beach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Colombia Mega II 1St – 30Th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report

Colombia Mega II 1st – 30th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report Black Manakin by Trevor Ellery Trip Report compiled by tour leader: Trevor Ellery Trip Report – RBL Colombia - Mega II 2016 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Top ten birds of the trip as voted for by the Participants: 1. Ocellated Tapaculo 6. Blue-and-yellow Macaw 2. Rainbow-bearded Thornbill 7. Red-ruffed Fruitcrow 3. Multicolored Tanager 8. Sungrebe 4. Fiery Topaz 9. Buffy Helmetcrest 5. Sword-billed Hummingbird 10. White-capped Dipper Tour Summary This was one again a fantastic trip across the length and breadth of the world’s birdiest nation. Highlights were many and included everything from the flashy Fiery Topazes and Guianan Cock-of- the-Rocks of the Mitu lowlands to the spectacular Rainbow-bearded Thornbills and Buffy Helmetcrests of the windswept highlands. In between, we visited just about every type of habitat that it is possible to bird in Colombia and shared many special moments: the diminutive Lanceolated Monklet that perched above us as we sheltered from the rain at the Piha Reserve, the showy Ochre-breasted Antpitta we stumbled across at an antswarm at Las Tangaras Reserve, the Ocellated Tapaculo (voted bird of the trip) that paraded in front of us at Rio Blanco, and the male Vermilion Cardinal, in all his crimson glory, that we enjoyed in the Guajira desert on the final morning of the trip. If you like seeing lots of birds, lots of specialities, lots of endemics and enjoy birding in some of the most stunning scenery on earth, then this trip is pretty unbeatable. -

Chlorospingus Flavovirens Rediscovered, with Notes on Other Pacific Colombian and Cauca Valley Birds

CHLOROSPINGUS FLAVOVIRENS REDISCOVERED, WITH NOTES ON OTHER PACIFIC COLOMBIAN AND CAUCA VALLEY BIRDS STEVEN L. HILTY ABSTRACT.--Aspecimen of the Yellow-green Bush Tanager collectedin 1972 was the first Colombianand third known specimensince the previoustwo taken in Ecuadorin 1935,and the specieshas not been reported since. Presentsnotes and new recordsof 36 other speciesfrom this region of high endemismon the westernslopes of the westernAndes.--Department of Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson,Arizona 85721. Accepted2 June 1975. THE Pacific slope of Colombia records the highest annual rainfall in the Western Hemisphere (Rumney 1968), yet the distribution of many birds in this unique region of high endemism is still known chiefly through early collections(e.g. Cassin 1860; Bangs 1908, 1910; Chapman 1917) and the extensive collectionsof Von Sheidern (fide Meyer de Schauensee)during 1938, 1940, 1941, 1945, and 1946. This and other information has been compiledby Meyer de Schauensee(1948-52, 1964, 1966, 1970). Recent papers by Haffer (1967a, 1967b), Miller (1966), Olivares (1957a, 1957b, 1958), and Ralph and Chaplin (1973) contributeto our knowledgeof Pacific Colom- bian avifauna but the status of many speciesis still poorly known. The data reported here were obtained during portions of 1972, 1973 and 1975, chiefly in the AnchicayJ Valley at low to moderate elevationson the west slopeof the westernAndes and in the upper Cauca Valley near Cali, Department of Valle. Llano Bajo, Aguaclara, Saboletas,Danubio, and La Cascada, mentioned in text, are small villagesalong the Old BuenaventuraRoad, southof Buenaventura. Yatacu• is a site administered by the Corporaci6n Aut6noma del Valle del Cauca (C.V.C.) in the upper Anchicay/t Valley above the confluenceof the Rio Digua and Rio An- chicay/t. -

Field Guides Tour Report Colombia: Cali Escape 2019

Field Guides Tour Report Colombia: Cali Escape 2019 Nov 2, 2019 to Nov 10, 2019 Jesse Fagan & Daniel Uribe For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Our birding group at the summit of Montezuma in the Tatama National Park. There is permanent military outpost here to protect the communications towers. The soldiers are always happy to see birding groups. This is the site for Chestnut-bellied Flowerpiercer and Munchique Wood-Wren. We started the tour in one of the two major economic and political centers of the region, Santiago de Cali (or just "Cali"), in the southern part of the Cauca Valley. Medellin, the other large metropolitan city, is a few hours north where the valley begins to narrow considerably. The Cauca Valley is pinned to the west by the Western Cordillera and to the east by the Central Cordillera, both splinter ranges of the Andes Mountains. This valley is known for its large sugercane production, and as a result, its famous rum. We made our first stop on the east slope of the Eastern Cordillera at El 18 and Finca Alejandria. This was a nice way to 'ease' ourselves into the diverse and intense birding we would be experiencing over the next few days. The feeders (both hummingbird and fruit) at Finca Alejandria teemed with exotic tanagers (including Multicolored), honeycreepers, toucanets (Crimson-rumped and Southern Emerald), and colorful and fancy hummingbirds. We made our first lunch attempt at bandeja paisa (for some) before descending into the valley and our first night in Buga. -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

ECUADOR: the Andes Introtour and High Andes Extension 10Th- 19Th November 2019

Tropical Birding - Trip Report Ecuador: The Andes Introtour, November 2019 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour ECUADOR: The Andes Introtour and High Andes Extension th th 10 - 19 November 2019 TOUR LEADER: Jose Illanes Report and photos by Jose Illanes Andean Condor from Antisana National Park This is one Tropical Birding’s most popular tours and I have guided it numerous times. It’s always fun and offers so many memorable birds. Ecuador is a wonderful country to visit with beautiful landscapes, rich culture, and many friendly people that you will meet along the way. Some of the highlights picked by the group were Andean Condor, White-throated Screech-Owl, Giant Antpitta, Jameson’s Snipe, Giant Hummingbird, Black-tipped Cotinga, Sword-billed Hummingbird, Club-winged Manakin, Lyre-tailed Nightjar, Lanceolated Monklet, Flame-faced Tanager, Toucan Barbet, Violet-tailed Sylph, Undulated Antpitta, Andean Gull, Blue-black Grassquit, and the attractive Blue-winged Mountain-Tanager. Our total species count on the trip (including the extension) was around 368 seen and 31 heard only. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report Ecuador: The Andes Introtour, November 2019 Torrent Duck at Guango Lodge on the extension November 11: After having arrived in Quito the night before, we had our first birding this morning in the Yanacocha Reserve owned by the Jocotoco Foundation, which is not that far from Ecuador’s capital. Our first stop was along the entrance road near a water pumping station, where we started out by seeing Streak- throated Bush-Tyrant, Brown-backed Chat-Tyrant, Cinereous Conebill, White-throated Tyrannulet, a very responsive Superciliaried Hemispingus, Black-crested Warbler, and the striking Crimson-mantled Woodpecker. -

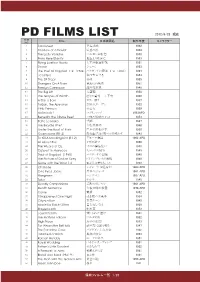

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

The Relationships of the Silky Flycatchers

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE SILKY FLYCATCHERS CI-IARLES G. SIBLE¾ THE silky flycatchersinclude the generaPtilogonys, Phainopepla, and Phainoptila,which are usuallytreated either as a family, Ptilogonatidae (e.g. Wetmore 1960), or as a subfamily of the waxwing family Bomby- cillidae (e.g. Greenway1960). Someauthors have includedthe Palm Chat (Dulus dominicus)of Hispaniola and the Grey Hypocolius (Hypocolius ampelinus) of Iraq and Iran in the Bombycillidae (Arvey 1951, Mayr and Amadon1951). Othershave consideredsome of theseallocations to be tentative or unproved and have recognizedseparate families for some or all of these groups (e.g. Wetmore 1960, Greenway 1960). The silky flycatchersare confinedto North and Central America. The Phainopepla(Phainopepla nitens) occursin the arid and semiaridregions of the southwestern United States and in Mexico south to Puebla and Vera Cruz. The Gray Silky Flycatcher (Ptilogonyscinereus) is a montane speciesranging from northwesternand easternMexico to Guatemala. The Long-tailedSilky Flycatcher(P. caudatus)and the Black-and-yellowSilky Flycatcher (Phainoptilamelanoxantha) are eachendemic to the highlands of Costa Rica and western Panama. This paper reviews some of the taxonomichistory and charactersof the silky flycatchersand presentsnew evidencefrom studies of the egg- white proteins indicating that they are closely related to the genus Myadestes,the solitaires,of the thrushfamily Turdidae. The two species of the genusEntomodestes of northwesternSouth America may be part of this natural cluster,but their egg whites have not been available for comparison. TAXONOMIC H•STOR¾ or THE S•LK¾ FLYCATCHERS AND A•;L•ES Ptilogonyscinereus, the first of the group to be discovered,was described by Swainsonin 1824. Swainsonalso describedthe Phainopepla (1837), which he placed in Ptilogonys. -

Seabird Harvest in Iceland Aever Petersen, the Icelandic Institute of Natural History

CAFF Technical Report No. 16 September 2008 SEABIRD HARVEST IN THE ARCTIC CAFFs CIRCUMPOLAR SEABIRD GROUP Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Directorate for Nature Management, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of the Environment and Nature, Greenland Homerule, Greenland (Kingdom of Denmark) • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska This publication should be cited as: Merkel, F. and Barry, T. (eds.) 2008. Seabird harvest in the Arctic. CAFF International Secretariat, Circumpolar Seabird Group (CBird), CAFF Technical Report No. 16. Cover photo (F. Merkel): Thick-billed murres, Saunders Island, Qaanaaq, Greenland. For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.caff.is ___ CAFF Designated Area Editing: Flemming Merkel and Tom Barry Design & Layout: Tom Barry Seabird Harvest in the Arctic Prepared by the CIRCUMPOLAR SEABIRD GROUP (CBird) CAFF Technical Report No. 16 September 2008 List of Contributors Aever Petersen John W. Chardine The Icelandic Institute of Natural History Wildlife Research Division Hlemmur 3, P.O. Box 5320 Environment Canada IS-125 Reykjavik, ICELAND P.O. Box 6227 Email: [email protected], Tel: +354 5 900 500 Sackville, NB E4L 4K2 CANADA Bergur Olsen Email: [email protected], Tel: +1-506-364-5046 Faroese Fisheries Laboratory Nóatún 1, P.O. -

Ornithological Observations from Reserva Natural Tambito, Cauca, South-West Colombia

Ornithological observations from Reserva Natural Tambito, Cauca, south-west Colombia Thomas M. Donegan and Liliana M. Dávalos Cotinga 12 (1999): 48– 55 Este artículo describe la avifauna de la Reserva Natural Tambito, una importante reserva con instalaciones para ecoturismo e investigación. Los autores realizaron dos estudios estandarizados en 1997 y 1998, cuyos resultados representan la mayor parte de los datos sobre la avifauna de la reserva: unas 313 especies fueron registradas incluyendo cuatro globalmente amenazadas y nueve casi-amenazadas. Es posible que también existan otras especies con problemas de conservación. También se presentan nuevos registros altitu d in ales y de distribución. También rendimos un sentido homenaje a Alvaro Negret — cuya trágica muerte en agosto de 1998 representa una pérdida considerable para la ornitología y la conservación en Colombia. Alvaro proveyó los fondos, tiempo y energía para establecer la Fundación Proselva y la Reserva Natural Tambito, excelente localidad para el estudio y observación de aves en Colombia. Introduction restricted-range bird species, the most of any EBA This paper seeks to portray the avifauna of an in the Neotropics18. Munchique and Tambito (site important nature reserve with facilities for CO53)20 is identified as one of Colombia’s most im ecotourists and researchers, and to pay tribute to portant key areas, known or suspected to contain Alvaro Negret — whose tragic death in August 1998 at least 10 threatened species — more than any other was a considerable loss to ornithology and site in Colombia20. conservation in Colombia. Alvaro provided the funds, time and energy to establish Fundación L o g is tic s Proselva and Reserva Natural Tambito. -

The Silly Symphonies Disney's First Fantasyland

X XIII THE SILLY SYMPHONIES DISNEY’S FIRST FANTASYLAND 3 PART I THE TIFFANY LINE 5 The Skeleton of an Idea 7 The Earliest Symphony Formula 9 Starting to Tell Tales Il Remaking Fairy Tales 18 Silly Toddlers and Their Families 19 Caste and Class in the Symphonies 21 An Exception to the Silly Rules: Three Little Pigs 22 Another Exception: Who Killed Cock Robin? 25 New Direction for the Symphonies at RKO 27 Ending in a Symphony Dream World 29 On a Final Note 31 PART Il PRODUCING THE SILLY SYMPHONIES 31 The ColurnbiaYears (1929-1932) 35 The United Artists Years (I932- 1937) 45 Disney’s RKO Radio Pictures (I937- 1939) 53 THE SKELETON DANCE (I929) I14 KING NEPTUNE (I932) a5 EL TERRIBLE TOREADOR (I 929) 115 BABES IN THE WOODS (I932) 58 SPRINGTIME (1929) I18 SANTA’S WORKSHOP (I 932) 50 HELL’S BELLS (I 929) 120 BIRDS IN THE SPRING (I933) 62 THE MERRY DWARFS (I929) I22 FATHER NOAH’S ARK (1933) 64 SUMMER (1930) i 24 THREE LITTLE PIGS (1933) 66 AUTUMN (I 930) I28 OLD KING COLE (1933) 58 CANNIBAL CAPERS (I 930) I30 LULLABY LAND (I 933) 7 NIGHT (I 930) I32 THE PIED PIPER (I933) 72 FROLICKING FISH (I 930) I34 THE CHINA SHOP (I933) É4 ARCTIC ANTICS (1930) I36 THE NIGHT BEFORE CHRISTMAS (I933) 76 MIDNIGHT IN ATOY SHOP (1930) I38 GRASSHOPPER AND THE ANTS (I 934) 78 MONKEY MELODIES (I 930) I49 THE BIG BAD WOLF (1934) no WINTER (I 930) i 42 FUNNY LITTLE BUNNIES (1934) 82 PLAYFUL PAN (I 930) I44 THE FLYING MOUSE (I 934) 84 BIRDS OF A FEATHER (I93 I) I46 THE WISE LITTLE HEN (I934) 86 MOTHER GOOSE MELODIES (I 93 I) 148 PECULIAR PENGUINS (1934) 88 THE CHINA PLATE -

Colombia Trip Report 1000 Birds Mega Tour 22Nd November to 20Th December 2013 (28 Days)

Colombia Trip Report 1000 Birds Mega Tour 22nd November to 20th December 2013 (28 days) White-capped Tanagers by Adam Riley Tour Leader(s): Forrest Rowland and Trevor Ellory Top 10 Tour Highlights (as voted by participants): 1. Santa Marta Screech-Owl 2. Guianan Cock-of-the-rock 3. Chestnut-crested Antbird 4. Azure-naped Jay 5. White-tipped Quetzal Trip Report - RBT Colombia Mega 2013 2 6. White-capped Tanager 7. Black-and-white Owl 8. Black Solitaire 9. Crested Ant Tanager 10. Bare-crowned Antbird Tour Intro Colombia has become iconic among Neotropical bird enthusiasts…that is to say, anybody who has ever seen a Cock-of-the-rock, Manakin lek, or hummingbird feeding station in the Andes! It is impossible to avoid falling in love with this diverse, impressive, stunning part of the world – and Colombia has the best of it. Guianan shield, Amazon Basin, three Andean ranges, tropical valleys, coastlines, and the famed Santa Marta Mountains are only what is NOW recognized as accessible. As time passes, access increases, and Colombia (rather than becoming more mundane) just becomes more mysterious as new species reveal themselves and new habitats become known, and we look to ever more remote parts of this complex nation. The mystery and wonder of Colombia, perhaps more than any other country, begged a challenge: is it possible for a commercial tour to record more than 1000 species of birds in less than a month? If so, Colombia was obviously the place to do it! The following is a much abbreviated account of one of the most spectacular journeys this author has ever embarked upon, and cannot possibly do justice to the marvelous sights, sounds, smells, and tastes one encounters after spending a whole month in Birder’s Paradise – Colombia! Tour Summary We all congregated in Colombia’s cosmopolitan capitol city Santa Fe de Bogota, on November 22nd, 2013.