Changes in a Scientific Concept: What Is a Planet? Mauro Murzi [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demoting Pluto Presentation

WWhhaatt HHaappppeenneedd ttoo PPlluuttoo??!!!! Scale in the Solar System, New Discoveries, and the Nature of Science Mary L. Urquhart, Ph.D. Department of Science/Mathematics Education Marc Hairston, Ph.D. William B. Hanson Center for Space Sciences FFrroomm NNiinnee ttoo EEiigghhtt?? On August 24th Pluto was reclassified by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as a “dwarf planet”. So what happens to “My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nine Pizzas”? OOffifficciiaall IAIAUU DDeefifinniittiioonn A planet: (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit. A dwarf planet must satisfy only the first two criteria. WWhhaatt iiss SScciieennccee?? National Science Education Standards (National Research Council, 1996) “…science reflects its history and is an ongoing, changing enterprise.” BBeeyyoonndd MMnneemmoonniiccss Science is “ not a collection of facts but an ongoing process, with continual revisions and refinements of concepts necessary in order to arrive at the best current views of the Universe.” - American Astronomical Society AA BBiitt ooff HHiiststoorryy • How have planets been historically defined? • Has a planet ever been demoted before? Planet (from Greek “planetes” meaning wanderer) This was the first definition of “planet” planet Latin English Spanish Italian French Sun Solis Sunday domingo domenica dimanche Moon Lunae Monday lunes lunedì lundi Mars Martis -

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

The First Discovery of an Aster Astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi in St

DISCOVERYDOM OF THE MONTHEDITORIAL 27(96), January 1, 2015 ISSN 2278–5469 EISSN 2278–5450 Discovery The first discovery of an asteroid, Ceres by Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi in January 1, 1801 Brindha V *Correspondence to: E-mail: [email protected] Publication History Received: 04 November 2014 Accepted: 01 December 2014 Published: 1 January 2015 Citation Brindha V. The first discovery of an asteroid, Ceres by Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi in January 1, 1801. Discovery, 2015, 27(96), 1 Publication License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. General Note Article is recommended to print as color digital version in recycled paper. Ceres was the first object considered to be an asteroid. The first asteroid discovered was 1 Ceres, or Ceres on January 1, 1801, by Giuseppe Piazzi a monk and astronomer in Sicily. It was classified as a planet for a long time and is considered a dwarf planet later. Asteroids are small, airless rocky worlds revolving around the sun that are too small to be called planets. They are also known as planetoids or minor planets. Ceres is the closest dwarf planet to the Sun and is located in the asteroid belt making it the only dwarf planet in the inner solar system. Ceres rotates on its axis every 9 hours and 4 minutes. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union voted to restore the planet designation to Ceres, decreeing that it qualifies as a dwarf planet. It does have some planet-like characteristics, including an interior that is separated into crust, mantle and core. -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

OMC | Data Export

Hanna Paulouskaya, "Entry on: Phaeton, the Son of Sun [Фаэтон – сын Солнца] by Vasily Livanov", peer-reviewed by Elżbieta Olechowska and Elizabeth Hale. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2019). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/798. Entry version as of September 30, 2021. Vasily Livanov Phaeton, the Son of Sun [Фаэтон – сын Солнца] Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (1972) TAGS: Greek mythology Helios Jupiter Phaeton Zeus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work Phaeton, the Son of Sun [Фаэтон – сын Солнца] Studio/Production Company Soyuzmultfilm Country of the First Edition Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) Country/countries of popularity Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Original Language Russian First Edition Date 1972 Фаэтон – сын Солнца [Phaeton, the Son of Sun]. Directed by First Edition Details Vasily Livanov. Script by V. Ankor and Vasily Livanov. Composer Gennady Gladkov. Moscow: Soyuzmultfilm, 1972, 17 min. 36 sec. Running time 17 min. 36 sec. Animated films, Hand-drawn animation (traditional animation)*, Genre Instructional and educational work, Short films Target Audience Crossover (Youth 6+) Author of the Entry Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, [email protected] Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, Peer-reviewer of the Entry [email protected] Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. -

Science in Nasa's Vision for Space Exploration

SCIENCE IN NASA’S VISION FOR SPACE EXPLORATION SCIENCE IN NASA’S VISION FOR SPACE EXPLORATION Committee on the Scientific Context for Space Exploration Space Studies Board Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. Support for this project was provided by Contract NASW 01001 between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors. International Standard Book Number 0-309-09593-X (Book) International Standard Book Number 0-309-54880-2 (PDF) Copies of this report are available free of charge from Space Studies Board National Research Council The Keck Center of the National Academies 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, DC 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area); Internet, http://www.nap.edu. Copyright 2005 by the National Academy of Sciences. -

An Overview of New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics About the National Academies

2020 VISION An Overview of New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics About the National Academies The National Academies—comprising the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council—work together to enlist the nation’s top scientists, engineers, health professionals, and other experts to study specific issues in science, technology, and medicine that underlie many questions of national importance. The results of their deliberations have inspired some of the nation’s most significant and lasting efforts to improve the health, education, and welfare of the United States and have provided independent advice on issues that affect people’s lives worldwide. To learn more about the Academies’ activities, check the website at www.nationalacademies.org. Copyright 2011 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America This study was supported by Contract NNX08AN97G between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Contract AST-0743899 between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Science Foundation, and Contract DE-FG02-08ER41542 between the National Academy of Sciences and the U.S. Department of Energy. Support for this study was also provided by the Vesto Slipher Fund. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the agencies that provided support for the project. 2020 VISION An Overview of New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics Committee for a Decadal Survey of Astronomy and Astrophysics ROGER D. -

Lecture 3 - Minimum Mass Model of Solar Nebula

Lecture 3 - Minimum mass model of solar nebula o Topics to be covered: o Composition and condensation o Surface density profile o Minimum mass of solar nebula PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum Mass Solar Nebula (MMSN) o MMSN is not a nebula, but a protoplanetary disc. Protoplanetary disk Nebula o Gives minimum mass of solid material to build the 8 planets. PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum mass of the solar nebula o Can make approximation of minimum amount of solar nebula material that must have been present to form planets. Know: 1. Current masses, composition, location and radii of the planets. 2. Cosmic elemental abundances. 3. Condensation temperatures of material. o Given % of material that condenses, can calculate minimum mass of original nebula from which the planets formed. • Figure from Page 115 of “Physics & Chemistry of the Solar System” by Lewis o Steps 1-8: metals & rock, steps 9-13: ices PY4A01 Solar System Science Nebula composition o Assume solar/cosmic abundances: Representative Main nebular Fraction of elements Low-T material nebular mass H, He Gas 98.4 % H2, He C, N, O Volatiles (ices) 1.2 % H2O, CH4, NH3 Si, Mg, Fe Refractories 0.3 % (metals, silicates) PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum mass for terrestrial planets o Mercury:~5.43 g cm-3 => complete condensation of Fe (~0.285% Mnebula). 0.285% Mnebula = 100 % Mmercury => Mnebula = (100/ 0.285) Mmercury = 350 Mmercury o Venus: ~5.24 g cm-3 => condensation from Fe and silicates (~0.37% Mnebula). =>(100% / 0.37% ) Mvenus = 270 Mvenus o Earth/Mars: 0.43% of material condensed at cooler temperatures. -

Thermonuclear AB-Reactors for Aerospace

1 Article Micro Thermonuclear Reactor after Ct 9 18 06 AIAA-2006-8104 Micro -Thermonuclear AB-Reactors for Aerospace* Alexander Bolonkin C&R, 1310 Avenue R, #F-6, Brooklyn, NY 11229, USA T/F 718-339-4563, [email protected], [email protected], http://Bolonkin.narod.ru Abstract About fifty years ago, scientists conducted R&D of a thermonuclear reactor that promises a true revolution in the energy industry and, especially, in aerospace. Using such a reactor, aircraft could undertake flights of very long distance and for extended periods and that, of course, decreases a significant cost of aerial transportation, allowing the saving of ever-more expensive imported oil-based fuels. (As of mid-2006, the USA’s DoD has a program to make aircraft fuel from domestic natural gas sources.) The temperature and pressure required for any particular fuel to fuse is known as the Lawson criterion L. Lawson criterion relates to plasma production temperature, plasma density and time. The thermonuclear reaction is realised when L > 1014. There are two main methods of nuclear fusion: inertial confinement fusion (ICF) and magnetic confinement fusion (MCF). Existing thermonuclear reactors are very complex, expensive, large, and heavy. They cannot achieve the Lawson criterion. The author offers several innovations that he first suggested publicly early in 1983 for the AB multi- reflex engine, space propulsion, getting energy from plasma, etc. (see: A. Bolonkin, Non-Rocket Space Launch and Flight, Elsevier, London, 2006, Chapters 12, 3A). It is the micro-thermonuclear AB- Reactors. That is new micro-thermonuclear reactor with very small fuel pellet that uses plasma confinement generated by multi-reflection of laser beam or its own magnetic field. -

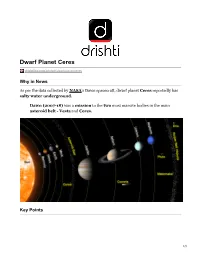

Dwarf Planet Ceres

Dwarf Planet Ceres drishtiias.com/printpdf/dwarf-planet-ceres Why in News As per the data collected by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, dwarf planet Ceres reportedly has salty water underground. Dawn (2007-18) was a mission to the two most massive bodies in the main asteroid belt - Vesta and Ceres. Key Points 1/3 Latest Findings: The scientists have given Ceres the status of an “ocean world” as it has a big reservoir of salty water underneath its frigid surface. This has led to an increased interest of scientists that the dwarf planet was maybe habitable or has the potential to be. Ocean Worlds is a term for ‘Water in the Solar System and Beyond’. The salty water originated in a brine reservoir spread hundreds of miles and about 40 km beneath the surface of the Ceres. Further, there is an evidence that Ceres remains geologically active with cryovolcanism - volcanoes oozing icy material. Instead of molten rock, cryovolcanoes or salty-mud volcanoes release frigid, salty water sometimes mixed with mud. Subsurface Oceans on other Celestial Bodies: Jupiter’s moon Europa, Saturn’s moon Enceladus, Neptune’s moon Triton, and the dwarf planet Pluto. This provides scientists a means to understand the history of the solar system. Ceres: It is the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It was the first member of the asteroid belt to be discovered when Giuseppe Piazzi spotted it in 1801. It is the only dwarf planet located in the inner solar system (includes planets Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars). Scientists classified it as a dwarf planet in 2006. -

Constraints on the Spin Evolution of Young Planetary-Mass Companions Marta L

Constraints on the Spin Evolution of Young Planetary-Mass Companions Marta L. Bryan1, Björn Benneke2, Heather A. Knutson2, Konstantin Batygin2, Brendan P. Bowler3 1Cahill Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, MC 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA. 2Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA. 3McDonald Observatory and Department of Astronomy, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA. Surveys of young star-forming regions have discovered a growing population of planetary- 1 mass (<13 MJup) companions around young stars . There is an ongoing debate as to whether these companions formed like planets (that is, from the circumstellar disk)2, or if they represent the low-mass tail of the star formation process3. In this study we utilize high-resolution spectroscopy to measure rotation rates of three young (2-300 Myr) planetary-mass companions and combine these measurements with published rotation rates for two additional companions4,5 to provide a look at the spin distribution of these objects. We compare this distribution to complementary rotation rate measurements for six brown dwarfs with masses <20 MJup, and show that these distributions are indistinguishable. This suggests that either that these two populations formed via the same mechanism, or that processes regulating rotation rates are independent of formation mechanism. We find that rotation rates for both populations are well below their break-up velocities and do not evolve significantly during the first few hundred million years after the end of accretion. This suggests that rotation rates are set during late stages of accretion, possibly by interactions with a circumplanetary disk. -

Exoplanet Discovery Methods (1) Direct Imaging Today: Star Wobbles (2) Astrometry → Position (3) Radial Velocity → Velocity

Exoplanet Discovery Methods (1) Direct imaging Today: Star Wobbles (2) Astrometry → position (3) Radial velocity → velocity Later: (4) Transits (5) Gravitational microlensing (6) Pulsar timing Kepler Orbits Kepler 1: Planet orbit is an ellipse with star at one focus Star’s view: (Newton showed this is due to gravity’s inverse-square law). Kepler 2: Planet seeps out equal area in equal time (angular momentum conservation). Planet’s view: Planet at the focus. Star sweeps equal area in equal time Inertial Frame: Star and planet both orbit around the centre of mass. Kepler Orbits M = M" + mp = total mass a = ap + a" = semi # major axis ap mp = a" M" = a M Centre of Mass P = orbit period a b a % P ( 2 a3 = G M ' * Kepler's 3rd Law b & 2$ ) a - b e + = eccentricity 0 = circular 1 = parabolic a ! Astrometry • Look for a periodic “wobble” in the angular position of host star • Light from the star+planet is dominated by star • Measure star’s motion in the plane of the sky due to the orbiting planet • Must correct measurements for parallax and proper motion of star • Doppler (radial velocity) more sensitive to planets close to the star • Astrometry more sensitive to planets far from the star Stellar wobble: Star and planet orbit around centre of mass. Radius of star’s orbit scales with planet’s mass: a m a M * = p p = * a M* + mp a M* + mp Angular displacement for a star at distance d: a & mp ) & a) "# = $ % ( + ( + ! d ' M* * ' d* (Assumes small angles and mp << M* ) ! Scaling to Jupiter and the Sun, this gives: ,1 -1 % mp ( % M ( % a ( % d ( "# $ 0.5 ' * ' + * ' * ' * mas & mJ ) & Msun ) & 5AU) & 10pc) Note: • Units are milliarcseconds -> very small effect • Amplitude increases at large orbital separation, a ! • Amplitude decreases with distance to star d.