A Textual Analysis of Nike's Women-Directed Advertisements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nike's Pricing and Marketing Strategies for Penetrating The

Master Degree programme in Innovation and Marketing Final Thesis Nike’s pricing and marketing strategies for penetrating the running sector Supervisor Ch. Prof. Ellero Andrea Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Camatti Nicola Graduand Sonia Vianello Matriculation NumBer 840208 Academic Year 2017 / 2018 SUMMARY CHAPTER 1: THE NIKE BRAND & THE RUNNING SECTOR ................................................................ 6 1.1 Story of the brand..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Foundation and development ................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.2 Endorsers and Sponsorships ...................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.3 Sectors in which Nike currently operates .................................................................................................. 8 1.2 The running market ........................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Competitors .................................................................................................................................... 12 1.4. Strategic and marketing practices in the market ............................................................................ 21 1.5 Nike’s strengths & weaknesses ...................................................................................................... -

Orange Bowl Committee

ORANGE BOWL COMMITTEE The Orange Bowl Committee ................................................................................................2 Orange Bowl Mission..............................................................................................................4 Orange Bowl in the Community ............................................................................................5 Orange Bowl Schedule of Events ......................................................................................6-7 The Orange Bowl and the Atlantic Coast Conference ......................................................8 Hard Rock Stadium ..................................................................................................................9 College Football Playoff ..................................................................................................10-11 QUICK FACTS Orange Bowl History........................................................................................................12-19 Orange Bowl Committee Orange Bowl Year-by-Year Results................................................................................20-22 14360 NW 77th Ct. Miami Lakes, FL 33016 Orange Bowl Game-By-Game Recaps..........................................................................23-50 (305) 341-4700 – Main (305) 341-4750 – Fax National Champions Hosted by the Orange Bowl ............................................................51 Capital One Orange Bowl Media Headquarters Orange Bowl Year-By-Year Stats ..................................................................................52-54 -

2020 UNC Women's Soccer Record Book

2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book 1 2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book Carolina Quick Facts Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. 2020 UNC Soccer Media Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents, Quick Facts........................................................................ 2 Established: December 11, 1789 (UNC is the oldest public university in the United States) 2019 Roster, Pronunciation Guide................................................................... 3 2020 Schedule................................................................................................. 4 Enrollment: 18,814 undergraduates, 11,097 graduate and professional 2019 Team Statistics & Results ....................................................................5-7 students, 29,911 total enrollment Misc. Statistics ................................................................................................. 8 Dr. Kevin Guskiewicz Chancellor: Losses, Ties, and Comeback Wins ................................................................. 9 Bubba Cunningham Director of Athletics: All-Time Honor Roll ..................................................................................10-19 Larry Gallo (primary), Korie Sawyer Women’s Soccer Administrators: Year-By-Year Results ...............................................................................18-21 Rich (secondary) Series History ...........................................................................................23-27 Senior Woman Administrator: Marielle vanGelder Single Game Superlatives ........................................................................28-29 -

List of All Olympics Prize Winners in Football in U.S.A

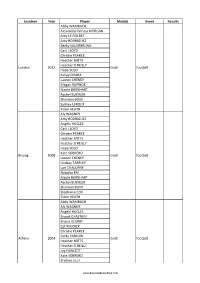

Location Year Player Medals Event Results Abby WAMBACH Alexandra Patricia MORGAN Amy LE PEILBET Amy RODRIGUEZ Becky SAUERBRUNN Carli LLOYD Christie PEARCE Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY London 2012 Gold football Hope SOLO Kelley OHARA Lauren CHENEY Megan RAPINOE Nicole BARNHART Rachel BUEHLER Shannon BOXX Sydney LEROUX Tobin HEATH Aly WAGNER Amy RODRIGUEZ Angela HUCLES Carli LLOYD Christie PEARCE Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY Hope SOLO Kate SOBRERO Beijing 2008 Gold football Lauren CHENEY Lindsay TARPLEY Lori CHALUPNY Natasha KAI Nicole BARNHART Rachel BUEHLER Shannon BOXX Stephanie COX Tobin HEATH Abby WAMBACH Aly WAGNER Angela HUCLES Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Cat REDDICK Christie PEARCE Cindy PARLOW Athens 2004 Gold football Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY Joy FAWCETT Kate SOBRERO Kristine LILLY www.downloadexcelfiles.com Lindsay TARPLEY Mia HAMM Shannon BOXX Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Carla OVERBECK Christie PEARCE Cindy PARLOW Danielle SLATON Joy FAWCETT Julie FOUDY Kate SOBRERO Sydney 2000 Silver football Kristine LILLY Lorrie FAIR Mia HAMM Michelle FRENCH Nikki SERLENGA Sara WHALEN Shannon MACMILLAN Siri MULLINIX Tiffeny MILBRETT Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Carin GABARRA Carla OVERBECK Cindy PARLOW Joy FAWCETT Julie FOUDY Kristine LILLY Atlanta 1996 Gold football 5 (4 1 0) 13 Mary HARVEY Mia HAMM Michelle AKERS Shannon MACMILLAN Staci WILSON Tiffany ROBERTS Tiffeny MILBRETT Tisha VENTURINI Alexander CUDMORE Charles Albert BARTLIFF Charles James JANUARY John Hartnett JANUARY Joseph LYDON St Louis 1904 Louis John MENGES Silver football 3 pts Oscar B. BROCKMEYER Peter Joseph RATICAN Raymond E. LAWLER Thomas Thurston JANUARY Warren G. BRITTINGHAM - JOHNSON Claude Stanley JAMESON www.downloadexcelfiles.com Cormic F. COSTGROVE DIERKES Frank FROST George Edwin COOKE St Louis 1904 Bronze football 1 pts Harry TATE Henry Wood JAMESON Joseph J. -

Imperialism and the 1999 Women's World Cup

IMPERIALISM AND THE 1999 WOMEN’S WORLD CUP: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES AND NIGERIAN NATIONAL TEAMS IN THE U.S. MEDIA by Michele Canning A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida April 2009 Copyright by Michele Canning 2009 ii ABSTRACT Author: Michele Canning Title: Imperialism and the 1999 Women’s World Cup: Representations of the United States and Nigerian National Teams in the U.S. Media Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Josephine-Beoku-Betts Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2009 This research examines the U.S. media during the 1999 Women’s World Cup from a feminist postcolonial standpoint. This research adds to current feminist scholarship on women and sports by de-centering the global North in its discourse. It reveals the bias of the media through the representation of the United States National Team as a universal “woman” athlete and the standard for international women’s soccer. It further argues that, as a result, the Nigerian National Team was cast in simplistic stereotypes of race, class, ethnicity, and nation, which were often also appropriated and commodified. I emphasize that the Nigerian National Team resisted this construction and fought to secure their position in the global soccer landscape. I conclude that these biased representations, which did not fairly depict or value the contributions of diverse competing teams, were primarily employed to promote and sell the event to a predominantly white middle-class American audience. -

Disney Extends Casey Powell Lacrosse Clinic

Disney Extends Casey Powell Lacrosse Clinic LAKE BUENA VISTA, Fla. – (Aug. 5, 2011) — High School and collegiate lacrosse teams training at ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex will continue to tap into the expertise of one of the most recognized names in lacrosse as a result of a longer-term agreement with lacrosse superstar Casey Powell. ‘I can’t think of a better place to help them (young players) reach their potential than Disney; the place where dreams come true.’ —Casey Powell ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex and Powell have extended their partnership that began last year, making the sports complex at Walt Disney World the official spring training home of Casey Powell Lacrosse for the next several years. Powell is this year’s World Indoor Lacrosse Championships MVP and one of the all-time greats in the Major Lacrosse League and National Lacrosse League. All teams participating in the Disney Lacrosse Spring Training program at the sports complex will receive a one-hour session with Casey Powell Lacrosse trainers. “It is an incredible feeling to know I have the opportunity to make a difference in the careers of young lacrosse players,” said Powell. “I can’t think of a better place to help them reach their potential than Disney; the place where dreams come true.” “It will be an extraordinary benefit for the young athletes in our Disney Sports Lacrosse Spring Training program to continue to be exposed to someone of Casey Powell’s stature,” said Disney Sports Development Manager Jeff Sturgeon. “This will be a one-of-a-kind experience that will provide these athletes and teams with the kind of world- class training, insight, knowledge and inspiration that they likely can’t get anywhere else.” The overall Disney Sports spring training program at ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex encompasses more than 700 high school and collegiate teams and 13,000 athletes nationwide in five different sports (baseball, softball, lacrosse, golf and track & field) from February through April. -

Sport» : Quadranta

Police «Sport» : Quadranta Sport ÉDITO Le conseil départemental de l’Allier est un partenaire incontournable du mouvement sportif dans notre département. Sport de haut niveau, sport de compétition, activités de pleine nature, sport pour tous, l’activité sportive se décline en une grande variété de pratiques sur l’ensemble du territoire. Le sport demeure un outil puissant de dynamisme, de cohésion sociale et d’épanouissement personnel. Il est aussi un prétexte à la découverte des atouts naturels de l’Allier et constitue un élément de son patrimoine culturel. Le sport, au-delà de ses vertus bien connues pour nos organismes, participe de manière importante à l’animation et donc à l’attractivité de notre département. Le Conseil départemental s’engage fortement auprès des acteurs du sport afin de favoriser un développement équilibré des activités sportives sur l’ensemble du territoire, à destination du plus grand nombre. À ce titre, nous sommes heureux d’accompagner le travail réalisé par l’USEP et l’UNSS aux côtés de nos jeunes. Nous accompagnons également la maison départementale des sports, lieu majeur de convivialité et d’échanges entre les sportifs. Nous apportons aussi notre soutien aux clubs et aux sportifs qui évoluent au niveau national. Vous le voyez, le Conseil départemental s’implique pour faire de l’Allier un vaste terrain de jeu propice au développement et à la pratique du sport. Cette soirée constitue également l’occasion de saluer l’engagement de Vichy communauté en faveur du sport et sa labelisation Terre de Jeux 2024. Nous vous souhaitons donc, à toutes et à tous, une excellente année sportive. -

Nike's “Just Do It” Advertising Campaign

Mini-case Study: Nike’s “Just Do It” Advertising Campaign According to Nike company lore, one of the most famous and easily recognized slogans in advertising history was coined at a 1988 meeting of Nike’s ad agency Wieden and Kennedy and a group of Nike employees. Dan Weiden, speaking admiringly of Nike’s can-do attitude, reportedly said, “You Nike guys, you just do it.” The rest, as they say, is (advertising) history. After stumbling badly against archrival Reebok in the 1980s, Nike rose about as high and fast in the ‘90s as any company can. It took on a new religion of brand consciousness and broke advertising sound barriers with its indelible Swoosh, “Just Do It” slogan and deified sports figures. Nike managed the deftest of marketing tricks: to be both anti-establishment and mass market, to the tune of $9.2 billion dollars in sales in 1997. —Jolie Soloman “When Nike Goes Cold” Newsweek, March 30, 1998 The Nike brand has become so strong as to place it in the rarified air of recession-proof consumer branded giants, in the company of Coca- Cola, Gillette and Proctor & Gamble. Brand management is one of Nike’s many strengths. Consumers are willing to pay more for brands that they judge to be superior in quality, style and reliability. A strong brand allows its owner to expand market share, command higher prices and generate more revenue than its competitors. With its “Just Do It” campaign and strong product, Nike was able to increase its share of the domestic sport-shoe business from 18 percent to 43 percent, from $877 million in worldwide sales to $9.2 billion in the ten years between 1988 and 1998. -

8 August 2000

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY FOURTIETH SESSION 23 JULY - 8 AUGUST 2000 1 © 2001 International Olympic Committee Published and edited jointly by the International Olympic Committee and the International Olympic Academy 2 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 40TH SESSION FOR YOUNG PARTICIPANTS SPECIAL SUBJECT: OLYMPIC GAMES: ATHLETES AND SPECTATORS 23 JULY - 8 AUGUST 2000 ANCIENT OLYMPIA 3 EPHORIA (BOARD OF DIRECTORS) OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY President Nikos FILARETOS IOC Member Honorary life President Juan Antonio SAMARANCH IOC President 1st Vice-president George MOISSIDIS Member of the Hellenic Olympic Committee 2nd Vice-president Spiros ZANNIAS Honorary Vice-president Nikolaos YALOURIS Member ex-officio Lambis NIKOLAOU IOC Member President of the Hellenic Olympic Committee Dean Konstantinos GEORGIADIS Members Dimitris DIATHESSOPOULOS Secretary General of the Hellenic Olympic Committee Georgios YEROLIMBOS Ioannis THEODORAKOPOULOS President of the Greek Association of Sports Journalists Epaminondas KIRIAZIS Cultural Consultant Panagiotis GRAVALOS 4 IOC COMMISSION FOR CULTURE AND OLYMPIC EDUCATION President Zhenliang HE IOC member in China Vice-president Nikos FILARETOS IOC member in Greece Members Fernando Ferreira Lima BELLO IOC member in Portugal Valeriy BORZOV IOC member in Ukraine Ivan DIBOS IOC member in Peru Sinan ERDEM IOC member in Turkey Nat INDRAPANA IOC member in Thailand Carol Anne LETHEREN t IOC member in Canada Francis NYANGWESO IOC member in Uganda Lambis W. NIKOLAOU IOC member in Greece Mounir SABET IOC member in -

Hoping for a Return on Investment in the Cowlitz Pete Caster / [email protected] Judy C

Celebrating the Swedes Large Crowds Flock to Rochester to Let Their Inner Viking Out / Main 3 Hiker Found Dead / Main 5 $1 Early-Week Edition Tuesday, June 24, 2014 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Hoping for a Return on Investment in the Cowlitz Pete Caster / [email protected] Judy C. Chain sits with her attorney, Sam Experimental Run of Salmon, Net Pens to Yield Better Harvest Groberg, during the irst day of her trial in Lewis County Superior Court on Monday. Trial for ‘Rising Son’ Head Starts ACCUSED: Judy Chafin Faces 30 Felony Charges for Allegedly Collecting $90,000 From Labor and Industries While Running the Controversial Group of Halfway Houses By Stephanie Schendel [email protected] At the peak of the House of the Rising Son organization, Judy Cha- fin ran numerous halfway houses for recently released convicts throughout Pete Caster / [email protected] Lewis County. Mossyrock Fish Hatchery Supervisor Tim Summers feeds fall chinook on Monday morning at the Mayield Net Pen Project at Silver Creek. The Washington De- She collected rent, went grocery partment of Fish and Wildlife is raising nearly 2 million fall chinook in these pins. The ish will eventually be released in the lower Cowlitz River near the salmon shopping for the tenants, enforced hatchery. house rules and dealt with all finan- cial transactions of the business. All FISH STORY: Money Secured in Part by Sen. John the while, she was allegedly collect- Braun Put to Use on Mayfield Lake ing disability checks from the De- partment of Labor and Industries, By Dameon Pesanti claiming she was unable to work. -

Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: a Closed Marketplace Christopher J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 13 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: A Closed Marketplace Christopher J. McKinny Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Christopher J. McKinny, Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: A Closed Marketplace, 13 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 223 (2003) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol13/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PROFESSIONAL SPORTS LEAGUES AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT: A CLOSED MARKETPLACE 1. INTRODUCTION: THE CONTROVERSY Get murdered in a second in the first degree Come to me with faggot tendencies You'll be sleeping where the maggots be... Die reaching for heat, leave you leaking in the street Niggers screaming he was a good boy ever since he was born But fluck it he gone Life must go on Niggers don't live that long' Allen Iverson, 2 a.k.a. "Jewelz," 3 from the song "40 Bars." These abrasive lyrics, quoted from Allen Iverson's rap composition "40 Bars," sent a shock-wave of controversy throughout the National Basketball 1. Dave McKenna, Cheap Seats: Bum Rap, WASH. CITY PAPER, July 6-12, 2001, http://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/archives/cheap/2001/cheap0706.html (last visited Jan. 15, 2003). 2. Allen Iverson, a 6-foot, 165-pound shooting guard, currently of the Philadelphia 76ers, was born June 7, 1975 in Hampton, Virginia. -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1.