Preface1 Alan Paton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WITHOUT FEAR OR FAVOUR the Scorpions and the Politics of Justice

WITHOUT FEAR OR FAVOUR The Scorpions and the politics of justice David Bruce Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation [email protected] In May 2008 legislation was tabled in Parliament providing for the dissolution of the Directorate of Special Operations (known as the ‘Scorpions’), an investigative unit based in the National Prosecuting Authority. The draft legislation provides that Scorpions members will selectively be incorporated into a new investigative unit located within the SAPS. These developments followed a resolution passed at the African National Congress National Conference in Polokwane in December 2007, calling for the unit to be disbanded. Since December the ANC has been forced to defend its decision in the face of widespread support for the Scorpions. One of the accusations made by the ANC was that the Scorpions were involved in politically motivated targeting of ANC members. This article examines the issue of political manipulation of criminal investigations and argues that doing away with the Scorpions will in fact increase the potential for such manipulation thereby undermining the principle of equality before the law. he origins of current initiatives to do away Accordingly we have decided not to with the Scorpions go back several years. In prosecute the deputy president (Mail and T2001 the National Prosecuting Authority Guardian online 2003). (NPA) approved an investigation into allegations of corruption in the awarding of arms deal contracts. Political commentator, Aubrey Matshiqi has argued In October 2002 they announced that this probe that this statement by Ngcuka ‘has in some ways would be extended to include allegations of bribery overshadowed every action taken in relation to against Jacob Zuma, then South Africa’s deputy Zuma by the NPA since that point.’ Until June president. -

Undamaged Reputations?

UNDAMAGED REPUTATIONS? Implications for the South African criminal justice system of the allegations against and prosecution of Jacob Zuma AUBREY MATSHIQI CSVRCSVR The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF VIOLENCE AND RECONCILIATION Criminal Justice Programme October 2007 UNDAMAGED REPUTATIONS? Implications for the South African criminal justice system of the allegations against and prosecution of Jacob Zuma AUBREY MATSHIQI CSVRCSVR The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Supported by Irish Aid ABOUT THE AUTHOR Aubrey Matshiqi is an independent researcher and currently a research associate at the Centre for Policy Studies. Published by the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation For information contact: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation 4th Floor, Braamfontein Centre 23 Jorissen Street, Braamfontein PO Box 30778, Braamfontein, 2017 Tel: +27 (11) 403-5650 Fax: +27 (11) 339-6785 http://www.csvr.org.za © 2007 Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. All rights reserved. Design and layout: Lomin Saayman CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 1. Introduction 5 2. The nature of the conflict in the ANC and the tripartite alliance 6 3. The media as a role-player in the crisis 8 4. The Zuma saga and the criminal justice system 10 4.1 The NPA and Ngcuka’s prima facie evidence statement 10 4.2 The judiciary and the Shaik judgment 11 5. The Constitution and the rule of law 12 6. Transformation of the judiciary 14 7. The appointment of judges 15 8. The right to a fair trial 17 9. Public confidence in the criminal justice system 18 10. -

We Should Learn from Mugabe, Says South Africa's Deputy Leader by Basildon Peta in Johannesburg Published: 12 August 2005

Independent Online Edition > Africa : app1 12 August 2005 10:14 Home ❍ > News ■ > World ■ > Africa We should learn from Mugabe, says South Africa's deputy leader By Basildon Peta in Johannesburg Published: 12 August 2005 South Africa's new Deputy President, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, has caused an uproar by calling for her country to copy Zimbabwe's disastrous land reform policies in an attempt to speed up redistribution. Mrs Mlambo-Ngcuka's remarks came shortly after a government summit to review South Africa's land reforms opted to drop the willing buyer/willing seller policy in favour of a new policy yet to be spelt out. "Land reform in South Africa has been too slow and too structured. There needs to be a bit of 'oomph'. That's why we may need the skills of Zimbabwe to help us," she said at an education conference. "On agrarian and land reform, South Africa should learn some lessons from Zimbabwe - how to do it fast." But analysts and opposition MPs, who fear South Africa is already on the path to losing its status as the world's sixth-biggest net food exporter following the rejection of the willing buyer/willing seller policy, condemned Mrs Mlambo Ngcuka's comments as "grossly irresponsible". While the need to redistribute land in South Africa to redress colonial-era imbalances is not disputed, there is almost universal consensus that Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe's methods are textbook examples of how not to enact land reforms. Murphy Morobe, head of communication at the presidency, later attempted to dismiss the comments, saying they were made in jest in a lighthearted moment during the conference: "The Deputy President made this remark during a light-hearted exchange between her and [the Minister for Higher Education, Dr Stan] Mudenge, whom she knows," he explained. -

A History of the Progressive Federal Party, 1981 - 1989

STRUCTURAL CRISIS AND LIBERALISM: A HISTORY OF THE PROGRESSIVE FEDERAL PARTY, 1981 - 1989 DAVID SHANDLER Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Economic History, Faculty of Arts, University of Cape Town, January 1991 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. .ABSTRACT Whereas an extensive literature has developed on the broad conditions of crisis in South Africa in the seventies and eighties, and on the dynamic of state and popular responses to it, little focus has fallen .on the reactions . of the other key elements among the dominating classes. It is the aim of this dissertation to attempt to address an aspect of this lacuna by focussing on the Progressive Federal Party's responses from 1981 until 1989. The thesis develops an understanding of the period as one entailing conditions of organ.le crisis. It attempts to show the PFP' s behaviour in the context of structural and conjunctural crises. The thesis periodises the Party's policy and strategic responses and makes an effort to show its contradictory nature. An effort is made to understand this contradictory character in terms of the party's class location with respect to the white dominating classes and leading elements within it; in relation to the black dominated classes; as well as in terms of the liberal tradition within which the Party operated. -

Struggle for Liberation in South Africa and International Solidarity A

STRUGGLE FOR LIBERATION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY A Selection of Papers Published by the United Nations Centre against Apartheid Edited by E. S. Reddy Senior Fellow, United Nations Institute for Training and Research STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED NEW DELHI 1992 INTRODUCTION One of the essential contributions of the United Nations in the international campaign against apartheid in South Africa has been the preparation and dissemination of objective information on the inhumanity of apartheid, the long struggle of the oppressed people for their legitimate rights and the development of the international campaign against apartheid. For this purpose, the United Nations established a Unit on Apartheid in 1967, renamed Centre against Apartheid in 1976. I have had the privilege of directing the Unit and the Centre until my retirement from the United Nations Secretariat at the beginning of 1985. The Unit on Apartheid and the Centre against Apartheid obtained papers from leaders of the liberation movement and scholars, as well as eminent public figures associated with the international anti-apartheid movements. A selection of these papers are reproduced in this volume, especially those dealing with episodes in the struggle for liberation; the role of women, students, churches and the anti-apartheid movements in the resistance to racism; and the wider significance of the struggle in South Africa. I hope that these papers will be of value to scholars interested in the history of the liberation movement in South Africa and the evolution of United Nations as a force against racism. The papers were prepared at various times, mostly by leaders and active participants in the struggle, and should be seen in their context. -

From Gqogqora to Liberation: the Struggle Was My Life

FROM GQOGQORA TO LIBERATION: THE STRUGGLE WAS MY LIFE The Life Journey of Zollie Malindi Edited by Theodore Combrinck & Philip Hirschsohn University of the Western Cape in association with Diana Ferrus Publishers IN THE SAME SERIES Married to the Struggle: ‘Nanna’ Liz Abrahams Tells her Life Story, edited by Yusuf Patel and Philip Hirschsohn. Published by the University of the Western Cape. Zollie Malindi defies his banning order in 1989 (Fruits of Defiance, B. Tilley & O. Schmitz 1990) First published in 2006 by University of the Western Cape Modderdam Road Bellville 7535 South Africa © 2006 Zolile (Zollie) Malindi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owner. Front and back cover illustrations by Theodore Combrinck. ISBN 0-620-36478-5 Editors: Theodore Combrinck and Philip Hirschsohn This book is available from the South African history online website: www.sahistory.org.za Printed and bound by Printwize, Bellville CONTENTS Acknowledgements Preface – Philip Hirschsohn and Theodore Combrinck Foreword – Trevor Manuel ZOLLIE MALINDI’S LIFE STORY 1 From a Village near Tsomo 2 My Struggle with Employment 3 Politics in Cape Town 4 Involvement in Unions 5 Underground Politics 6 Banned, Tortured, Jailed 7 Employment at Woolworths 8 Political Revival in the 1980s 9 Retirement and Reflections Bibliography ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to Graham Goddard, of the Robben Island Museum’s Mayibuye Archive located at the University of the Western Cape, for locating photographic and video material. -

General Plenary Meeting

United Nations 53rd GENERAL PLENARY MEETING ASSEMBLY Wednesday, 3 November 1976, THIRTY·FIRST SESSION at 11 a.m. Official Records NEW YORK CONTENTS Council was unable to impose an arms embargo on South 4 . Page Africa owing to the triple veto cast in the Council by the Agenda item 52: United States, the United Kingdom and France-a shameful Policies of apartheid of the Government of South Africa episode in the history of these three countries, which (continued): (a) Report of the Special Committee against Apartheid; uphold the principles of international law, human riglits (b) Report of the Secretary-General . 877 and self-determination when regimes within their orbit are ~ .\ not involved but flout the same principles whenever their President: Mr. Hamilton Shirley AMERASINGHE racist allies and regimes maintaining cultural, economic and (Sri Lanka). political relations with them, like South Africa, Rhodesia and Israel, are concerned. 3. The policy of apartheid and racial segregation is not AGENDA ITEM 52 only an affront to mankind and human dignity, but also a violation of all human, moral and cultural values. it is also a Policies of apartheid of the Government of South Africa crime which has no less grave significance or results than (continued): nazism or any other ideology based on racial, religious or (a) Report of the Special Committee against Apartheid; cultural superiority. And if the international community (b) Report of the Secretary-General decided to pass judgement on the criminals of nazism and I to condemn them to death for -

Timol Draft 3/30/05 10:23 AM Page 1

Timol draft 3/30/05 10:23 AM Page 1 TIMOL A QUEST FOR JUSTICE Imtiaz Cajee Timol draft 3/30/05 10:23 AM Page 2 First published in 2005 by STE Publishers 4th Floor, Sunnyside Ridge, Sunnyside Office Park, 32 Princess of Wales Terrace, Parktown, 2143, Johannesburg, South Africa First published February 2005 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission of both the copyright holder and the publisher of the book. © Imtiaz Cajee 2005 © Photographs as credited Cover photograph of Johannesburg Central (formerly John Vorster Square) by Peter McKenzie. This is the building where Ahmed Timol died. An open window in the picture is reminiscent of the window through which Timol allegedly “jumped”. Extract used in Chapter 9, Inquest are from No One To Blame by George Bizos, David Phillip Publishers Cape Town, 1998 ISBN 1-919855-40-8 Editor: Tony Heard Editorial Consultant: Ronald Suresh Roberts Copy Editor: Barbara Ludman Proofreader: Michael Collins Indexer: Mirie Van Rooyen Cover design: Adam Rumball Typesetting: Mad Cow Studio Set in 10 on 12 pt Minion Printed and bound by Creda Communications Cape Town This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Interactions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies

UCLA InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies Title Featured Commentary: Nelson Mandela, Memory, and the Work of Justice Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4ng874xp Journal InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies, 8(2) ISSN 1548-3320 Author Harris, Verne Publication Date 2012 DOI 10.5070/D482011855 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Preface1 Alan Paton (1903-1988) believed in the power of memory. He also warned against its dangers, and fought tirelessly against its abuse. He was a friend of African National Congress President and Nobel Peace Prize winner Chief Albert Luthuli. He was a political adversary of Nelson Mandela. A writer, anti-apartheid activist, and politician, he was most famous for his bestselling novel, Cry, the Beloved Country, and for his leadership role in the Liberal Party. He gave evidence in support of mitigating the prison sentence for Mandela and the others being tried in the Rivonia Trial in 1964. Years later, Mandela wrote him from prison, thanking him for his support. The letter was intercepted by the prison censors and never reached Paton. Let me say at once that I am honoured to be associated with Alan Paton in this way. And that my institution, the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, is similarly honoured. My aim with this [Alan Paton] Lecture is to honour Paton’s memory by reflecting on the roles of memory in the beloved country during the era we call post-apartheid, postcolonial. Introduction -

Mrs. Helen Suzman: Lone Progressive Tamboer S Kloof Cape Town South Afriea

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS March 16, 1962 JCB-7 29 Bay View Avenue Mrs. Helen Suzman: Lone Progressive Tamboer s Kloof Cape Town South Afriea Mr. Richard H. Nolte Institute of Current World Affairs 366 adison Avenue New York 17, New York Dear Mr. Nolte: I had tea the other day w+/-h Mrs. Helen Suzman, the only lember of Parliament to stand publcly for an undivided multi-racial South Africa. This small and attractive Progressive Party MP from Houghton is one of a very few women %o make a successful career n politics and, since she was the only Progressive to retain a seat in the MRS. HELEN SUZMAN last election, she now bears the full HOUGHTON responsibility for keeping the spirit of her party alive in an antagonistic Parlament. Quite a job for a 45 year old mother of college-age daughters. Never content wth domesticity, although she celebrates her 25%h Wedding Anniversary this year, she started lecturing on economic development at the University of Wtwatersrand, in 3ohannes- burg, soon after the irth of her children. At about the same time she became nterested n politics, spurred by the Institute of Race Relations which asked her %o prepare evidence for the Fagan Commission Report n 1948. She became active n the Women's Councl of the United Party, and in 1953 she was persuaded %o stand as the UP candidate for the House of Assembly from Houghton. An unopposed vctory in this electon started her somewhat stormy trek %o the lone poston she holds today. -

Ahmed Timol Was the First Detainee to Die at John Vorster Square

“He hung from a piece of soap while washing…” In Detention, Chris van Wyk, 1979 On 23 August 1968, Prime Minister Vorster opened a new police station in Johannesburg known as John Vorster Square. Police described it as a state of the art facility, where incidents such as the 1964 “suicide” of political detainee, Suliman “Babla” Saloojee, could be avoided. On 9 September 1964 Saloojee fell or was thrown from the 7th floor of the old Gray’s Building, the Special Branch’s then-headquarters in Johannesburg. Security police routinely tortured political detainees on the 9th and 10th floors of John Vorster Square. Between 1971 and 1990 a number of political detainees died there. Ahmed Timol was the first detainee to die at John Vorster Square. 27 October 1971 – Ahmed Timol 11 December 1976 – Mlungisi Tshazibane 15 February 1977 – Matthews Marwale Mabelane 5 February 1982 – Neil Aggett 8 August 1982 – Ernest Moabi Dipale 30 January 1990 – Clayton Sizwe Sithole 1 Rapport, 31 October 1971 Courtesy of the Timol Family Courtesy of the Timol A FAMILY ON THE MOVE Haji Yusuf Ahmed Timol, Ahmed Timol’s father, was The young Ahmed suffered from bronchitis and born in Kholvad, India, and travelled to South Africa in became a patient of Dr Yusuf Dadoo, who was the 1918. In 1933 he married Hawa Ismail Dindar. chairman of the South African Indian Congress and the South African Communist Party. Ahmed Timol, one of six children, was born in Breyten in the then Transvaal, on 3 November 1941. He and his Dr Dadoo’s broad-mindedness and pursuit of siblings were initially home-schooled because there was non-racialism were to have a major influence on no school for Indian children in Breyten. -

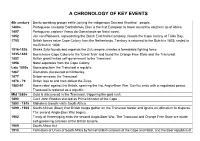

A Chronology of Key Events

A CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS 4th century Bantu speaking groups settle, joining the indigenous San and Khoikhoi people. 1480s Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias is the first European to travel round the southern tip of Africa. 1497 Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama lands on Natal coast. 1652 Jan van Riebeeck, representing the Dutch East India Company, founds the Cape Colony at Table Bay. 1795 British forces seize Cape Colony from the Netherlands. Territory is returned to the Dutch in 1803; ceded to the British in 1806. 1816-1826 Shaka Zulu founds and expands the Zulu empire, creates a formidable fighting force. 1835-1840 Boers leave Cape Colony in the 'Great Trek' and found the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. 1852 British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal. 1856 Natal separates from the Cape Colony. Late 1850s Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic. 1867 Diamonds discovered at Kimberley. 1877 Britain annexes the Transvaal. 1878 - 79 British lose to and then defeat the Zulus 1880-81 Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic. Mid 1880s Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. 1890 Cecil John Rhodes elected as Prime Minister of the Cape 1893 - 1915 Mahatma Gandhi visits South Africa 1899 - 1902 South African (Boer) War British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins. 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire.