Monarchs' Names and Numbering in the Second Bulgarian State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Posthumously Conceived Children: an International and Human Rights Perspective Maya Sabatello Columbia University Law School

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Journal of Law and Health Law Journals 2014 Posthumously Conceived Children: An International and Human Rights Perspective Maya Sabatello Columbia University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/jlh Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Recommended Citation Maya Sabatello, Posthumously Conceived Children: An International and Human Rights Perspective , 27 J.L. & Health 29 (2014) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/jlh/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Health by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POSTHUMOUSLY CONCEIVED CHILDREN: AN INTERNATIONAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS PERSPECTIVE MAYA SABATELLO, LLB, PHD I. THE PHENOMENON OF POSTHUMOUS CONCEPTION ..................... 30 II. POSTHUMOUS CONCEPTION IN COURTS ...................................... 38 III. THE LEGAL DISCOURSE ON POSTHUMOUSLY CONCEIVED CHILDREN ................................................................................... 41 IV. POSTHUMOUSLY CONCEIVED CHILDREN .................................... 56 A. Parentage Acknowledgement .......................................... -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

August 2010 PROTECTION of AUTHOR ' S C O P Y R I G H T This

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 ASSISTED HUMAN REPRODUCTION: POSTHUMOUS USE OF GAMETES ALISON JANE DOUGLASS A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Bioethics and Health L.aw at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. December 15, 1998 ABSTRACT In the past posthumous reproduction has been primarily a result of accident or fate. More recently, the ability to freeze sperm and embryos (and the potential for use of stored ova) has lead to greater control over procreation and its timing in relation to the lives of ,. parents. The technology associated with posthumous reproduction is now commonplace, but the application of these techniques represents a subtle shift offocus from the technical aspects to the arguably insidious acceptance of this development. This thesis critically. reflects on both the ethical and legal considerations of posthumous use of sperm and particular implications -

175 Churches and Monasteries – Objects Of

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DERMENDZHIEV, Athanas,; DOYKOV, Martin (2017). The Churches and Monasteries – objects of religious tourism in the district of Veliko …. The Overarching Issues of the European Space: Society, Economy and Heritage in a Scenario … Porto: FLUP, pp. 175‐183 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CHURCHES AND MONASTERIES – OBJECTS OF RELIGIOUS TOURISM IN THE DISTRICT OF VELIKO TARNOVO (BULGARIA) Athanas DERMENDZHIEV Department of Geography, Faculty of History, “St. Cyril and St. Methodius” University of Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria [email protected] Martin DOYKOV Department of Geography, Faculty of History, “St. Cyril and St. Methodius” University of Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria. [email protected] Abstract The need of focusing on the significance of religious tourist sites and objects in the region of Veliko Tarnovo is provoked by socio-economic necessities. The last presume activation of cultural-historical resources with a view to the interest to the available objects. Religion, as spirit and interaction, presumes corresponding objectification. The last one is a segment in the formation of religious-tourist bank for its exploitation in spiritual-nationalistic direction. Recognized by Bulgarians as an ozonizing areal, the region of Veliko Tarnovo presumes fixing on values of cultural-historical content. Their studying and the explanation of their existence -

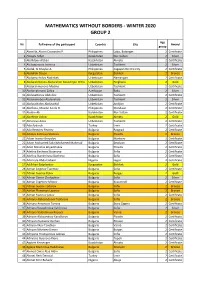

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Lobo, Batangas 2 Certificate 2 Abayev Aidyn Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Silver 3 Abdildaev Alzhan Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Certificate 4 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 5 Abdul, Al Khaylar A. Philippines Cagayan De Oro City 2 Certificate 6 Abdullah Dayan Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Bronze 7 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 8 Abdurahmonov Abdurahim Boxodirjon O'G'Li Uzbekistan Ferghana 2 Gold 9 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 10 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Silver 11 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 13 Abduvohidov Abduvohid Uzbekistan Andijon 2 Certificate 14 Abellana, Maxine Anela O. Philippines Mandaue 2 Certificate 15 Abildin Ali Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Certificate 16 Abirkhan Adina Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Gold 17 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 18 Ada Aydınok Turkey Izmir 2 Certificate 19 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 20 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Bronze 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Certificate 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 24 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Stanimirova Docheva Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adenrele Abdul Jabaar Nigeria Lagos 2 Certificate -

The Rise of Bulgarian Nationalism and Russia's Influence Upon It

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it. Lin Wenshuang University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wenshuang, Lin, "The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1548. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1548 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Lin Wenshuang All Rights Reserved THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Approved on April 1, 2014 By the following Dissertation Committee __________________________________ Prof. -

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521837561 - Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185- 1365 Istvan Vasary Table of Contents More information Contents Preface page xi 1 Introduction 1 Remarks on the sources 1 Cumans and Tatars 4 2 Cumans and the Second Bulgarian Empire 13 The antecedents and outbreak of the liberation movement 13 Bulgars, Vlakhs and Cumans before 1185 17 Ethnic names and ethnic realities in the sources of the Second Bulgarian Empire 22 Bulgaria, Vlakhia and Cumania in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries 27 Origins and possible Cuman affiliations of the Asen dynasty 33 Peter and Asen versus Isaakios and Alexios Angeloi: the first phase of the Cumano-Vlakho-Bulgarian league’s fight against Byzantium, 1186–1197 42 Kaloyan and his Cumans against Byzantium and the Latins 47 The Cumans’ role in the restoration of Bulgaria 54 3 Cumans in the Balkans before the Tatar conquest, 1241 57 Cumans during the reign of Boril, 1207–1218 57 Cumans during the reign of Ivan Asen II until 1237 61 Two waves of Cuman immigration to Bulgaria and the Latin Empire, 1237, 1241 63 Cumans in the service of John Batatzes and Theodoros II, 1241–1256 67 4 The first period of Tatar influence in the Balkans, 1242–1282 69 The Tatar conquest in the Balkans 69 Prince Nogay 71 The Tatars release ‘Izzadd¯ın in Thrace, 1264 72 Nogay’s marriage to a Byzantine princess, 1272 79 The Tatars’ role in the struggle for the Bulgarian throne, 1277–1280 79 Tatars invited to punish Sebastokrator Ioannes of Thessaly, 1282 84 vii © Cambridge University -

Nominalia of the Bulgarian Rulers an Essay by Ilia Curto Pelle

Nominalia of the Bulgarian rulers An essay by Ilia Curto Pelle Bulgaria is a country with a rich history, spanning over a millennium and a half. However, most Bulgarians are unaware of their origins. To be honest, the quantity of information involved can be overwhelming, but once someone becomes invested in it, he or she can witness a tale of the rise and fall, steppe khans and Christian emperors, saints and murderers of the three Bulgarian Empires. As delving deep in the history of Bulgaria would take volumes upon volumes of work, in this essay I have tried simply to create a list of all Bulgarian rulers we know about by using different sources. So, let’s get to it. Despite there being many theories for the origin of the Bulgars, the only one that can show a historical document supporting it is the Hunnic one. This document is the Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans, dating back to the 8th or 9th century, which mentions Avitohol/Attila the Hun as the first Bulgarian khan. However, it is not clear when the Bulgars first joined the Hunnic Empire. It is for this reason that all the Hunnic rulers we know about will also be included in this list as khans of the Bulgars. The rulers of the Bulgars and Bulgaria carry the titles of khan, knyaz, emir, elteber, president, and tsar. This list recognizes as rulers those people, who were either crowned as any of the above, were declared as such by the people, despite not having an official coronation, or had any possession of historical Bulgarian lands (in modern day Bulgaria, southern Romania, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, and northern Greece), while being of royal descent or a part of the royal family. -

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775-831

Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editor Florin Curta VOLUME 16 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/ecee Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 By Panos Sophoulis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Cover illustration: Scylitzes Matritensis fol. 11r. With kind permission of the Bulgarian Historical Heritage Foundation, Plovdiv, Bulgaria. Brill has made all reasonable efforts to trace all rights holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sophoulis, Pananos, 1974– Byzantium and Bulgaria, 775–831 / by Panos Sophoulis. p. cm. — (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, ISSN 1872-8103 ; v. 16.) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20695-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Byzantine Empire—Relations—Bulgaria. 2. Bulgaria—Relations—Byzantine Empire. 3. Byzantine Empire—Foreign relations—527–1081. 4. Bulgaria—History—To 1393. I. Title. DF547.B9S67 2011 327.495049909’021—dc23 2011029157 ISSN 1872-8103 ISBN 978 90 04 20695 3 Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Post-Mortem Sperm Retrieval and the Social Security Administration: How Modern Reproductive Technology Makes Strange Bedfellows Mary F

Georgia State University College of Law Reading Room Faculty Publications By Year Faculty Publications 1-1-2009 Post-Mortem Sperm Retrieval and the Social Security Administration: How Modern Reproductive Technology Makes Strange Bedfellows Mary F. Radford Georgia State University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/faculty_pub Part of the Elder Law Commons, Family Law Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary F. Radford, Post-Mortem Sperm Retrieval and the Social Security Administration: How Modern Reproductive Technology Makes Strange Bedfellows, 2 Est. Plan. & Community Prop. L.J. 33 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications By Year by an authorized administrator of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POSTMORTEM SPERM RETRIEVAL AND THE SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION: HOW MODERN REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGY MAKES STRANGE BEDFELLOWS by Mary F. Radford I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 33 HI. RELEVANT LEGISLATION ................................................................. 38 A. ParentageStatutes ................................................................... 39 B. Inheritance Statutes ................................................................ 41 III. PMSR AND SOCIAL SECURITY: THE CASE OF VERNOFF V. A STR UE ............................................................................................ -

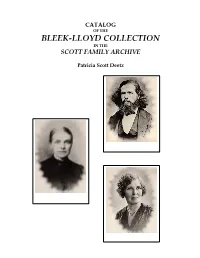

Bleek-Lloyd Collection in the Scott Family Archive

CATALOG OF THE BLEEK-LLOYD COLLECTION IN THE SCOTT FAMILY ARCHIVE Patricia Scott Deetz © 2007 Patricia Scott Deetz Published in 2007 by Deetz Ventures, Inc. 291 Shoal Creek, Williamsburg, VA 23188 United States of America Cover Illustrations Wilhelm Bleek, 1868. Lawrence & Selkirk, 111 Caledon Street, Cape Town. Catalog Item #84. Lucy Lloyd, 1880s. Alexander Bassano, London. Original from the Scott Family Archive sent on loan to the South African Library Special Collection May 21, 1993. Dorothea Bleek, ca. 1929. Navana, 518 Oxford Street, Marble Arch, London W.1. Catalog Item #200. Copies made from the originals by Gerry Walters, Photographer, Rhodes University Library, Grahamstown, Cape 1972. For my Bleek-Lloyd and Bright-Scott-Roos Family, Past & Present & /A!kunta, //Kabbo, ≠Kasin, Dia!kwain, /Han≠kass’o and the other Informants who gave Voice and Identity to their /Xam Kin, making possible the remarkable Bleek-Lloyd Family Legacy of Bushman Research About the Author Patricia (Trish) Scott Deetz, a great-granddaughter of Wilhelm and Jemima Bleek, was born at La Rochelle, Newlands on February 27, 1942. Trish has some treasured memories of Dorothea (Doris) Bleek, her great-aunt. “Aunt D’s” study was always open for Trish to come in and play quietly while Aunt D was focused on her Bushman research. The portraits and photographs of //Kabbo, /Han≠kass’o, Dia!kwain and other Bushman informants, the images of rock paintings and the South African Archaeological Society ‘s logo were as familiar to her as the family portraits. Trish Deetz moved to Williamsburg from Charlottesville, Virginia in 2001 following the death of her husband James Fanto Deetz. -

I. E Best of Sofia Page 11

WELCOME! ! You are in Soia, the , capital city of the Republic . e of Bulgaria. In your hands “ – ”, you are holding the informa- tion guide Soia – european - destination, which will enable . you to get acquainted with the - – best of Soia and its sights. - You are looking for busi- . ness contacts? Open the pages of the business guide 7 000 , and you will ind the partner you need. - More than 7000 years have passed since the irst in , habitants settled at the foot of the Vitosha Mountains, , near the numerous curative mineral springs, laying . the foundations of this ancient city. Wise were also , , the irst builders of our state, who after the Liberation of Bulgaria from Ottoman domination decided the , city, bearing the name of the Goddess . , of Wisdom, Sophia, to be the capital of Bulgaria. , . Soia is a cosmopolitan city, a political, cultural and , economic centre of one of the oldest European states, - which has survived to this day. A crossroads of civiliza , tions, for centuries on end it has been a bridge between . the East and the West, between Europe and Asia. The new political realities, the accession of – Bulgaria as a full-ledged member of the European . Union, hold out new economic opportunities and , ideal conditions for contacts and business. A grow- . ing number of leading world companies open ofices , in the capital city, attracted by the strategic location , and the low corporate taxes. Apart from the business opportunities, Soia is . 3 000 , , an attractive tourist destination. Hundreds of ho- , tels, some of which are part of world hotel chains, offer you cosiness and hospitality.