Post-Mortem Sperm Retrieval and the Social Security Administration: How Modern Reproductive Technology Makes Strange Bedfellows Mary F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Posthumously Conceived Children: an International and Human Rights Perspective Maya Sabatello Columbia University Law School

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Journal of Law and Health Law Journals 2014 Posthumously Conceived Children: An International and Human Rights Perspective Maya Sabatello Columbia University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/jlh Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Recommended Citation Maya Sabatello, Posthumously Conceived Children: An International and Human Rights Perspective , 27 J.L. & Health 29 (2014) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/jlh/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Health by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POSTHUMOUSLY CONCEIVED CHILDREN: AN INTERNATIONAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS PERSPECTIVE MAYA SABATELLO, LLB, PHD I. THE PHENOMENON OF POSTHUMOUS CONCEPTION ..................... 30 II. POSTHUMOUS CONCEPTION IN COURTS ...................................... 38 III. THE LEGAL DISCOURSE ON POSTHUMOUSLY CONCEIVED CHILDREN ................................................................................... 41 IV. POSTHUMOUSLY CONCEIVED CHILDREN .................................... 56 A. Parentage Acknowledgement .......................................... -

August 2010 PROTECTION of AUTHOR ' S C O P Y R I G H T This

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 ASSISTED HUMAN REPRODUCTION: POSTHUMOUS USE OF GAMETES ALISON JANE DOUGLASS A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Bioethics and Health L.aw at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. December 15, 1998 ABSTRACT In the past posthumous reproduction has been primarily a result of accident or fate. More recently, the ability to freeze sperm and embryos (and the potential for use of stored ova) has lead to greater control over procreation and its timing in relation to the lives of ,. parents. The technology associated with posthumous reproduction is now commonplace, but the application of these techniques represents a subtle shift offocus from the technical aspects to the arguably insidious acceptance of this development. This thesis critically. reflects on both the ethical and legal considerations of posthumous use of sperm and particular implications -

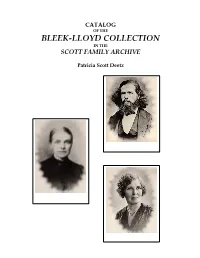

Bleek-Lloyd Collection in the Scott Family Archive

CATALOG OF THE BLEEK-LLOYD COLLECTION IN THE SCOTT FAMILY ARCHIVE Patricia Scott Deetz © 2007 Patricia Scott Deetz Published in 2007 by Deetz Ventures, Inc. 291 Shoal Creek, Williamsburg, VA 23188 United States of America Cover Illustrations Wilhelm Bleek, 1868. Lawrence & Selkirk, 111 Caledon Street, Cape Town. Catalog Item #84. Lucy Lloyd, 1880s. Alexander Bassano, London. Original from the Scott Family Archive sent on loan to the South African Library Special Collection May 21, 1993. Dorothea Bleek, ca. 1929. Navana, 518 Oxford Street, Marble Arch, London W.1. Catalog Item #200. Copies made from the originals by Gerry Walters, Photographer, Rhodes University Library, Grahamstown, Cape 1972. For my Bleek-Lloyd and Bright-Scott-Roos Family, Past & Present & /A!kunta, //Kabbo, ≠Kasin, Dia!kwain, /Han≠kass’o and the other Informants who gave Voice and Identity to their /Xam Kin, making possible the remarkable Bleek-Lloyd Family Legacy of Bushman Research About the Author Patricia (Trish) Scott Deetz, a great-granddaughter of Wilhelm and Jemima Bleek, was born at La Rochelle, Newlands on February 27, 1942. Trish has some treasured memories of Dorothea (Doris) Bleek, her great-aunt. “Aunt D’s” study was always open for Trish to come in and play quietly while Aunt D was focused on her Bushman research. The portraits and photographs of //Kabbo, /Han≠kass’o, Dia!kwain and other Bushman informants, the images of rock paintings and the South African Archaeological Society ‘s logo were as familiar to her as the family portraits. Trish Deetz moved to Williamsburg from Charlottesville, Virginia in 2001 following the death of her husband James Fanto Deetz. -

For a Falcon

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves CRESCENT BOOKS NEW YORK New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Translated by Richard Aldington and Delano Ames and revised by a panel of editorial advisers from the Larousse Mvthologie Generate edited by Felix Guirand and first published in France by Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie, the Librairie Larousse, Paris This 1987 edition published by Crescent Books, distributed by: Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10003 Copyright 1959 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited New edition 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. ISBN 0-517-00404-6 Printed in Yugoslavia Scan begun 20 November 2001 Ended (at this point Goddess knows when) LaRousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves Perseus and Medusa With Athene's assistance, the hero has just slain the Gorgon Medusa with a bronze harpe, or curved sword given him by Hermes and now, seated on the back of Pegasus who has just sprung from her bleeding neck and holding her decapitated head in his right hand, he turns watch her two sisters who are persuing him in fury. Beneath him kneels the headless body of the Gorgon with her arms and golden wings outstretched. From her neck emerges Chrysor, father of the monster Geryon. Perseus later presented the Gorgon's head to Athene who placed it on Her shield. -

Department of English

PAVENDAR BHARATHIDASAN COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE (AFFILIATED TO BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY) DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SUBJECT :FICTION SUB.CODE:16ACCEN4 UNIT-I David Copperfield - charles Dickens UNIT –II Treasure lsland -R.L.Stevenson UNIT-III Heart of darkness –joseph Conrad UNIT-IV To the lighthouse - Virginia woolf UNIT -V Brave new world –Aldous Huxley Prepared By T.Elakiya PABCAS 2 MARKS 1.what is the event with which david copperfield opens? David copperfied opens with the posthumous birth of david . his father has been dead for six month. 1 | P a g e 2.who is clara peggotty? Clara peggotty is the nurse and servant- maid in the copperfied home . she bring up david copperfied. 3.what is david’s attitude to Mr. murdstone? Mr.murdstone is david’s step-father. David does not like him . he is jealous of him. 4. who is barkis? Barkis is a carriage driver who takes david to salem house. 5.where does david stay in London? David stay in London with the micawber family who provide boarding. 6.where does david stay in Canterbury? David stay with the wickfield’s in Canterbury. 7.what is the name of the inn where bill bones stays? The name of the inn is admiral benbow. 8.how do people call bill bones? People call bill bones,captain. 9.how does bill bones describe doctors? bill bones describes doctors as swabs, that is, as men who are too soft to face diffcultiers. 10.how does bill bones describe rum? Bill bones says that rum is his meat and drink, and man and wife. -

Posthumour Children, Hegemonic Human Rights, and the Dilemma of Reform - Conservations Across Cultres Uche Ewerlukwa

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 19 Article 3 Number 2 Summer 2008 1-1-2008 Posthumour Children, Hegemonic Human Rights, and the Dilemma of Reform - Conservations Across Cultres Uche Ewerlukwa Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Uche Ewerlukwa, Posthumour Children, Hegemonic Human Rights, and the Dilemma of Reform - Conservations Across Cultres, 19 Hastings Women's L.J. 211 (2008). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol19/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Posthumous Children, Hegemonic Human Rights, and the Dilemma of Reform - Conversations Across Cultures Uch6 Ewelukwa" I. INTRODUCTION Mr. Nnanyelugo Nnebechi Okonkwo (Okonkwo), a native of Onitsha, a town in southeastern Nigeria, died in 1931.1 During his lifetime, Okonkwo had five male children.2 Thirty years after Okonkwo's death, his sisters, acting purportedly under Onitsha native law and custom, married a wife (X) on his behalf.3 X gave birth to six children who all bear Okonkwo's name.4 In a case that was fought all the way to the Nigerian Supreme Court (Supreme Court), the central questions before the Supreme Court were whether the living can legally contract a marriage on behalf of the dead and whether a man can procreate thirty years after his death. -

Assessing Assisted Reproductive Technology

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2018 Assessing Assisted Reproductive Technology Raymond C. O'Brien The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Medical Jurisprudence Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Raymond C. O'Brien, Assessing Assisted Reproductive Technology, 27 Cath. U. J. L. & Tech 1 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSESSING ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGY Raymond C. O’Brien I. Utilization of Assisted Reproduction ..............................................................7 A. Statistical Trends .......................................................................................8 1. ART Cycles and Births ...........................................................................8 2. Cryopreservation..................................................................................12 3. Age as a Factor in Utilizing ART .........................................................14 4. Embryos Transferred ...........................................................................15 5. -

Nietzsche's Revolution: Décadence, Politics, And

Nietzsche’s Revolution This page intentionally left blank Nietzsche’s Revolution Décadence, Politics, and Sexuality C. Heike Schotten nietzsche’s revolution Copyright © C. Heike Schotten, 2009. All rights reserved. First published in 2009 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978-0-230-61358-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Scribe Inc. First edition: August 2009 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America. For my parents, Peter and Bernice Schotten, who taught me to love and For my intellectual parents, Michael and Catherine Zuckert, who taught me to read Man vergilt einem Lehrer schlecht, wenn man immer nur der Schüler bleibt. [One repays a teacher poorly if one ever remains only a pupil.] Thus Spoke Zarathustra I:22(3) “On the Gift-Giving Virtue” [O]ften I have asked myself whether, taking a large view, philosophy has not been merely an interpretation of the body and a misunderstanding of the body. -

Reform of the Intestate Succession Act

ALBERTA LAW REFORM INSTITU'TE EDMONTON, ALBERTA REFORM OF THE INTESTATE SUCCESSION ACT Report for Discussion No. 16 January 1996 ISSN 0834-9037 ISBN 0-8886-4198-2 Table of Contents PART I -- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................... 1 PART I1 -- REPORT ........................................................ 5 CHAPTER1. INTRODUCTION A . History and Scope of Project ............................................... 5 B. Terminology ............................................................ 6 C . Outline of Report ........................................................ 7 CHAPTER2 . HISTORICALSKETCH AND OVERVIEWOF CANADIAN INTESTACYLEGISLATION A . History of Intestate Succession ............................................. 9 1. England ........................................................... 9 2 . Canada .......................................................... 10 3 . Alberta ........................................................... 11 4 . Uniform Intestate Succession Act ...................................... 12 B. Corr~parisonof Canadian Legislation and the Uniform Acts ...................... 13 1. Overview of legislative models ......................................... 13 a . Category I: Canadian mainstream .................................. 13 b . Category 2 Manitoba ............................................ 15 c . Category 3: Uniform Intestate Succession Act ......................... 16 d . Category 4: Uniform Probate Code (U.S.) ............................ 16 CHAPTER 3. TRENDSIN CANADIANSOCIETY A . Introduction -

Succession and Posthumously Conceived Children

Note: ALRI is currently revising its work in this area for a final report. Readers are advised that the interpretation of the Family Law Act s 8.1 presented at paras 26-30 is under review. SUCCESSION AND POSTHUMOUSLY CONCEIVED CHILDREN REPORT FOR DISCUSSION 23 JANUARY 2012 ISSN 0834-9037 ISBN 1-896078-49-4 ALRI claims copyright © in this work. ALRI encourages the availability, dissemination and exchange of public information. You may copy, distribute, display, download and otherwise freely deal with this work on the following conditions: (1) You must acknowledge the source of this work, (2) You may not modify this work, and (3) You must not make commercial use of this work without the prior written permission of ALRI. Invitation to Comment Deadline for comments on the issues raised in this document is June 30, 2012 Advances in artificial reproductive technologies have significantly increased the incidence of the use of these technologies. In addition, the ability to store genetic material for longer periods of time has led to the possibility of the genetic material being used for reproductive purposes after the death of the person who provided the genetic material. The law has addressed, and to some extent dealt with the legal issues raised by assisted reproduction, and many jurisdictions have new rules relating to parentage or succession rights. In Alberta, as in many other jurisdictions, the law has not yet addressed how to deal with relationships or rights which are created after the death of the donor of genetic material. Who is a parent? Has the deceased consented to posthumous use of the material? Should the child automatically have a relationship and inheritance rights from the deceased donor? The purpose of this report is to raise some of these issues, describe the legal concepts which are at play and ask whether the law ought to propose solutions to these issues. -

Medicine and New Jersey

MEDICINE AND NEW JERSEY Medical, Pharmaceutical and Health-Related Manuscripts in the Rutgers University Libraries MEDICINE AND NEW JERSEY Medical, Pharmaceutical and Health-Related Manuscripts in the Rutgers University Libraries By Albert C. King NOTE: This guide describes most, but not all, of the repository's core collections pertaining to the topic indicated. [Preliminary Edition: March 1998] Special Collections and University Archives Rutgers University Libraries Allinson family. Papers, 1761-1909 (bulk 1761-1798, 1809-1811, 1824-1883). ca. 1 cubic ft. (1 box and 4 v.). Quaker family of the mid-Atlantic region, including Burlington pharmacist William J. Allin- son (1810-1874). Summary: Included among the family's papers is a prescription book ["Liber X"], January- October 1854, recording "Prescriptions Compounded at the Pharmaceutical Establishment of William J. Allinson." This volume consists of an old daybook (begun 1795 for a general store in Burlington) into which approximately 2,784 filled prescriptions have been pasted. In addition to listing the medicine, each prescription typically (but not always) includes the patient's name, the date written, instructions for using what was prescribed, the initials of the prescribing phy- sician and a number (followed by an "X") assigned by the druggist. Inserted at the back of the volume is a loose page from a similar prescription book (in which the numbers use the suffix "z") kept in 1856. Prescription book disbound (detached boards present) and split into many separate gather- ings and single leaves. (Most or all of the loose leaves originally were conjugate with others, but one leaf from each pair was cut away to accomodate the physical bulk of the inserted pre- scriptions.) Call number: MC 796. -

The Tennessee Rule Against Perpetuities: a Proposal for Statutory Reform

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 27 Issue 6 Issue 6 - November 1974 Article 3 11-1974 The Tennessee Rule Against Perpetuities: A Proposal for Statutory Reform C. Dent Bostick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Common Law Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation C. Dent Bostick, The Tennessee Rule Against Perpetuities: A Proposal for Statutory Reform, 27 Vanderbilt Law Review 1153 (1974) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol27/iss6/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Tennessee Rule Against Perpetuities: A Proposal for Statutory Reform C. Dent Bostick* For several decades, there has been agitation for reform of the common-law Rule Against Perpetuities. For the most part, the re- formers have urged that improvements in the Rule and the manner of its application be accomplished through legislative enactment.' 2 Only a few jurisdictions have opted for reform by the judiciary. Thus far, there has been no legislative reform of the Rule in Tennes- see; the appellate courts of the state continue to apply the Rule in its common-law form with all the confusing rubrics attached to it by centuries of development. The condition of Tennessee's law on the subject contrasts sharply with that of neighboring Kentucky where significant reform has been achieved. 3 Considering the poten- tial for serious mischief and even catastrophic consequences in prop- erty and estate transactions when the common-law rule is applied, it seems appropriate to take a fresh look at the Rule and its applica- tion in Tennessee.