New Art West Midlands Catalogue 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesse Bruton 6 July – 11 September 2016

Ikon Gallery, 1 Oozells Square, Brindleyplace, Birmingham B1 2HS 0121 248 0708 / www.ikon-gallery.org Open Tuesday-Sunday, 11am-5pm / free entry Jesse Bruton 6 July – 11 September 2016 Jesse Bruton, Devil's Bowl (c.1965). Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist. Jesse Bruton is one of the founding artists of Ikon. This exhibition (6 July – 11 September 2016) tells the fascinating story of his artistic development, starting in the 1950s and ending in 1972 when Bruton abandoned painting for painting conservation. Having studied at the College of Art in Birmingham, Bruton was a lecturer there during the early 1960s, following a scholarship year in Spain and a stint of National Service. He went on to teach at the Bath Academy of Art, Corsham, 1966-69. He exhibited in a number of group shows in Birmingham, especially at the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, and had a solo exhibition at Ikon shortly after the gallery opened to the public in 1965, and again in 1967. Like many of his contemporaries, Bruton developed an artistic proposition inspired by landscape. Many of his early paintings were of the Welsh mountains and the Pembrokeshire coast. Alive to the aesthetic possibilities of places he visited, he made vivid painterly translations based on a stringent palette of black and white. They reflected his particular interest “in the way things worked, things like valleys, rock formations and rivers ...” “I wasn’t particularly interested in colour. I wanted to limit the formal language I was using – to work tonally gradating from black to white, leaching out the medium from the paint in order to enhance a variety of textures. -

Phantom Captain in Wakeathon

... • • • •• • • • •• • • • • • •• • • •I • • • • ' • • ( • ..• •.• ., .,,. .. , ••• .• • . • • •• • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • •"' • •. • .••• . ' . J '•• • - - • • • • • .• ...• • . • • • •• • • • • • • •• • ••• • ••••••••• • • • •••••• • • • • • • ••••• . • f • ' • • • ••• • •• • • •f • .• . • •• • • ., • , •. • • • •.. • • • • ...... ' • •. ... ... ... • • • • • ,.. .. .. ... - .• .• .• ..• . • . .. .. , • •• . .. .. .. .. • • • • .; •••• • •••••••• • 4 • • • • • • • • ••.. • • • •"' • • • • •, • -.- . ~.. • ••• • • • ...• • • ••••••• •• • 6 • • • • • • ..• -•• This issue of Performance Magazine has been reproduced as part of Performance Magazine Online (2017) with the permission of the surviving Editors, Rob La Frenais and Gray Watson. Copyright remains with Performance Magazine and/or the original creators of the work. The project has been produced in association with the Live Art Development Agency. NEW DANCE THEATRE IN THE '80s? THE ONLY MAGAZINE BY FOR AND ABOUT TODAYS DANCERS "The situation in the '80s will challenge live theatre's relevance, its forms, its contact with people, its experimentation . We believe the challenge is serious and needs response. We also believe that after a decade of 'consolidation' things are livening up again. Four years ago an Honours B.A. Degree in Theatre was set up at Dartington College of Arts to meet the challenge - combining practice and theory, working in rural and inner-city areas, training and experimenting in dancing, acting, writing, to reach forms that engage people. Playwrights, choreographers -

David Prentice 1936 – 2014

DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work - a Selling Retrospective: Part II Autumn 2017 Period, Modern & Contemporary Art DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work - a Selling Retrospective: PART II includes paintings of all periods but also features examples inspired by the Scilly Isles, City of London paintings, the Isle of Skye and The House that Jack Built. Saturday, 7th October 11am - 5pm Sunday, 8th October 11am - 3pm Continues through to 4th November Monday - Saturday 10am - 5pm Sligachan Bridge, Isle of Skye (2012) Watercolour, 23 x 33 ins The Old Dairy Plant · Fosseway Business Park · Stratford Road Moreton-in-Marsh · Gloucestershire · GL56 9NQ Front cover illustration: King’s Reach West (2003) Tel: 01608 652255 · email: [email protected] Oil on canvas, 46 x 56 ins www.johndaviesgallery.com DAVID PRENTICE 1936 – 2014 A Window on a Life’s Work: Part II From both a public perspective and a gallery point of view, range of what are widely regarded as under-appreciated part one of this two-part retrospective for David has been a works of art. distinctly rewarding and illuminating event. First and foremost, the throughput of visitors to the exhibition has been very high. Included in Part ll of A Window on a Life’s Work are five Secondly, the positive reaction of this elevated number of bodies of work – abstract works from the 1960’s and 1970’s observers to David’s work has been significant and voluble. (contrasting to those in Part I), a small group of significant and particularly dynamic paintings derived from the Scilly Isles, a I include in this ‘public’ many of David’s ex-pupils who have good number of the hugely impressive City of London displayed a strong, universal affection for their tutor of fifty canvasses; highly atmospheric works inspired by the Isle of years-ago. -

IPG+Adult+Fall+2019.Pdf

Fall 2019 Best-Selling Titles IPG – Fall 2019 9781948705110 9781604432565 9781947026025 9781947026186 9781935879510 9781936693771 9781771681452 9781613737002 9781641600415 9781613749418 9781613735473 9780914090359 9781613743416 9780897333764 9781613747964 9781556520747 9781682751596 9781555917432 9781555914639 9781555916329 9781682570890 9780918172020 9781940842110 9781940842004 9781940842080 IPG – Fall 2019 Best-Selling Titles 9781940842226 9781681121703 9781783055876 9781629635736 9781629635682 9781629635101 9781892005281 9781939650870 9781943156702 9781935622505 9781643280639 9781930064171 9780824519865 9780991399703 9781629376370 9781629376110 9781629376752 9781629377001 9781629376349 9781629376004 9781629375342 9781629374420 9781947597006 9781947597037 9781947597020 Fall 2019 Arts & Entertainment ������������������������������� 1–15 History & Humanities ���������������������������� 16–30 Comics & Graphic Novels ���������������������� 31–37 Fiction & Poetry������������������������������������� 38–66 Sports & Recreation ������������������������������ 67–79 Activities, Craft & Photography ��������������� 80–92 Health & Self-Help �������������������������������� 93–99 Religion & Spirituality ������������������������ 100–103 Business & Travel ������������������������������ 104–111 Index ������������������������������������������������ 112–114 IPG – FALL 2019 Arts & Entertainment Twisted: The Cookbook Team Twisted From social media powerhouse TWISTED comes a bold new collection of recipes that feature in videos garnering upwards of 400 -

Programme July – September 2014 Free Entry

Programme July – September 2014 www.ikon-gallery.org Free entry As Exciting As We Can Make It Rasheed Araeen Art & Language Ikon in the 1980s Sue Arrowsmith 2 July – 31 August 2014 Kevin Atherton First and Second Floor Galleries Terry Atkinson Gillian Ayres A survey of Ikon’s programme from the 1980s, Bernard Bazile As Exciting As We Can Make It, is a highlight of our Ian Breakwell 50th anniversary year. A comprehensive exhibition, Vanley Burke 2 including work by 29 artists, it features painting, Eddie Chambers sculpture, installation, film and photography actually Shelagh Cluett The 1980s saw the rise of postmodernism, a fast-moving shown at the gallery during this pivotal decade. Agnes Denes zeitgeist that chimed in with broader cultural shifts in Britain, in particular the politics that evolved under the Max Eastley premiership of Margaret Thatcher. There was a return to figurative painting; a shameless “appropriationism” that Charles Garrad saw artists ‘pick and mix’ from art history, non-western art and popular culture; and an enthusiastic re-embrace of Ron Haselden Dada and challenge to notions of self contained works of art Susan Hiller through an increasing popularity of installation. Ikon had a reputation by the end of the 1980s as a key John Hilliard national venue for installation art. Dennis Oppenheim’s Albert Irvin extraordinary work Vibrating Forest (From the Fireworks Series) (1982), made from welded steel, a candy floss machine and Tamara Krikorian unfired fireworks, returns to Ikon for the exhibition, as does Charles Garrad’s Monsoon (1986) featuring a small building, Pieter Laurens Mol set out as a restaurant somewhere in South East Asia, subjected to theatrical effects of thunder and lightning in an Mali Morris evocative scenario. -

From Birmingham to Belfast

UPLOAD: 1 December 2017 Special JEMS Forum: The EMC2 Festival, 24–26 March 2017, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK Sponsored by CoMA (Contemporary Music for All), Arts Council of England, and the University of Leicester From Birmingham to Belfast: improvising and experimenting with students Hilary Bracefield THERE is no doubt that the people behind the Experimental Catalogue (begun in 1968 by Chris Hobbs with Gavin Bryars and Michael Nyman joining in) were largely responsible for disseminating and fostering the rise in indeterminate music-making in the 1970s and 1980s in the United Kingdom. In Birmingham, however, the start of an experimental music group had another impetus. This article, based on a paper given to the EMC2 conference at De Montfort University in March 2017, is a personal account of the events in Birmingham from 1971 and in Belfast from 1977. The start of an improvisatory music group at Birmingham University must be credited to the lecturer Peter Dickinson. He had studied at Hilary Bracefield, paper, 24 March 2017 the Juilliard School in New York and encountered the music of John Cage, Henry Cowell and Edgard Varèse. On return to England he had worked on improvisatory music with students in London. Just before he left Birmingham to go to Keele University (where he set up an important centre for the study of American music) he collaborated in March 1971 with a lecturer in drama, Jocelyn Powell, to mount a performance of John Cage’s Theatre Piece (1960) in an evening concert at the Barber Institute at the university, a series to which the general public always came. -

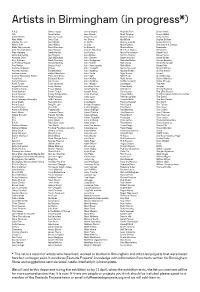

Artists in Birmingham (In Progress*)

Artists in Birmingham (in progress*) A.A.S. Darren Joyce Jenny Moore Michelle Bint Simon Davis A2rt Dave Patten Jess Hands Mick Thacker Simon Webb Adele Prince David A. Hardy Jesse Bruton Mike Holland Sofia Hulten Alan Miller David Cox Jim Byrne Mo White Sophie Bullock Alastair Scruton David Mabb Jo Griffin Mohammed Ali Space Banana Albert Toft David Miller Jo Loki Mona Casey Sparrow and Castice Aleks Wojtulewicz David Prentice Jo Roberts Monica Ross Spectacle Alex Gene Morrison David Rowan Joanne Masding Mrs G. A. Barton Steve Bell Alex Marzeta Derek Horton Joe Hallam Myria Panayiotou Steve Field Alicia Dubnyckyj Des Hughes Joe Welden Nathan Hansen Steve Payne Amanda Grist Dick McGowan John Barrett Nayan Kulkarni Steve Wilkes Amy Kirkham Dinah Prentice John Bridgeman Nicholas Bullen Steven Beasley An Endless Supply Donald Rodney John Butler Nick Jones Stuart Mugridge Ana Rutter Easton Hurd John Hammersley Nick Wells Stuart Tait Andrew Gillespie Ed Lea John Hodgett Nicola Counsell Stuart Whipps Andrew Jackson Ed Wakefield John Newling Nicolas Bullen Su Richardson Andrew Lacon Eddie Chambers John Poole Nigel Amson Surely? Andrew Moscardo Parker Eliza Jane Grose John Salt Nikki Pugh Surjit Simplay Andy Hunt Elizabeth Rowe John Walker Nola James Sylvani Merilion Andy Robinson Elly Clarke John Wallbank OHNE/projects Tadas Stalyga Andy Turner Emily Mulenga John Wigley Ole Hagen Ted Allen Angela Maloney Emily Warner Jonathan Shaw Oliver Braid Temper Angelina Davis Emma Macey Jony Easterby Ollie Smith Tereza Buskova Anna Barham Emma Talbot Joseph -

Geraldine Pilgrim

This issue of Performance Magazine has been reproduced as part of Performance Magazine Online (2017) with the permission of the surviving Editors, Rob La Frenais and Gray Watson. Copyright remains with Performance Magazine and/or the original creators of the work. The project has been produced in association with the Live Art Development Agency. IKON wo1-;n:; TELLING STO,iIES fa.3GvT 1:Cl"E!\ GALLERY Performance by Paul Burwell June 10 7.30pm Admission free t~ l~ Ikon Gallery ::tkl.,,. ~ M~ s-,,),,.fv1,v~ 58-72 John Bright St lr(i);IIKlll~JITit/till Birmingham B1 1 BN f>1E.,iri.., 0w~ ·M~c h'ffa,,«S~ ~<A:d ½ ~ y,.M -tHi;{ THE ALBANY EMPIRE THE DRILL HALL l)()l Cl.AS WAY, I.ONDON SES 16 (UENIES STREET , LONDON wn Tr.1in : Ucptford / New Cross . Tube : New Cro s~ Goott11:e Streel T ub e April 29- '\1a y 2, Ma ) -7- 9, Ma)· 14- 16 '1a) · 18--30 at 8.00 Tuesda y-Saturda y al 8.1~ pm. Sunday al 8.00 pm Sunday 6.00 pm Wednesday 19 Ma y at 7.00 pm BOX OFFICE : 01----6913333 BOX OFF ICE: 01-637 8270 Bar , Food, Musi(' & Dancing after sho"'°· LiC'ensed Bar & Good Food Our new address is: 14 PETOPLACEJ LONDONJ NWl 01 - 935 2714 This issue of Performance Magazine has been reproduced as part of Performance Magazine Online (2017) with the permission of the surviving Editors, Rob La Frenais and Gray Watson. Copyright remains with Performance Magazine and/or the original creators of the work. -

Hist 1968-1989 R.Cwk (WP)

NEXUS - History of Performances - p.1 (Becker, Cahn, Engelman, Wyre) 1968 Aug.17 Marlboro Music Festival, Vermont Stravinsky - Les Noces 1970 (Becker, Cahn) Nov.5 Rochester(NY)Strasenburgh Planetarium Nexus - improvisation 1971 WXXI-TV Local Broadcast - Rochester,NY Nexus - improvisation (Becker, Cahn, Engelman, Wyre) May 22 Kilbourn Hall, Eastman School of Music Nexus - improvisation May 23 Rochester First Unitarian Church Nexus - improvisation (Becker, Cahn) Oct.13 Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra w/Sam Jones Cahn - The Stringless Harp (Mirage?) (Becker, Cahn, Engelman, Wyre) Nov. 24 Hamilton(Ontario)Philharmoic Orchestra w/ B.Brott Wyre - Sculptured Sound 1972 (Becker, Cahn) Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra w/T.Virkhaus Cahn - The Stringless Harp (Becker, Cahn, Engelman, Wyre) May 13 Metropolitan United Church(Toronto) Nexus - improvisation (Becker, Cahn, Engelman, Hartenberger, Wyre) Aug.6 Marlboro Music Festival, Vermont Messiaen - Oiseaux Exotiques (Becker, Cahn, Craden, Engelman, Wyre) Aug.7 Shaw Festival (Music Today),Ontario Nexus - improvsation 1973 (Becker, Cahn, Craden, Engelman, Hartenberger, Wyre) Wesleyan University(Connecticut) Nexus with Adzinyah, Sumarsam, Peter Plotsky, Raghavan (Becker, Cahn, Craden, Tim Ferchen, Hartenberger) Jun.12 CBC Winnipeg Festival Nexus - improvisation (Becker, Cahn, Craden, Engelman, Hartenberger, Wyre) Jul.23 York University, Ontario Nexus - improvisation Jul.25 York University Nexus and Earle Birney Jul.26 York University Nexus and Pauline Oliveros Jul.30 York University Nexus and David -

Research and Cultural Collections: An

Research and Cultural Collections: An introduction Foreword 4 Introduction 6 The Danford Collection of West African Art and Artefacts 8 The Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity Museum 10 Collection of Historic Physics Instruments 12 The Biological Sciences Collection 14 Medical School Collection 16 The Silver and Plate Collection 18 University Heritage Collection 20 The Campus Collection of Fine and Decorative Art 22 What we do 28 Visit us 30 Map 30 Text by Clare Mullett, Assistant University Curator Acknowledgements: Karin Barber, Holly Grange, David Green, Graham Norrie, Jonathan Reinarz, Dave Roach, Gillian Shepherd, Chris Urwin, Sarah Whild, Robert Whitworth and Inga Wolf Graham Chorlton (b. 1953) View (detail). Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2008. The Danford Collection of West African Art and Artefacts 4 Research and Cultural Collections: An introduction Research and Cultural Collections Foreword by Dr James Hamilton, University Curator Following an initiative taken in 1991 by the then Vice- The germ from which all university collections develop is The University’s art collections grew from the 1960s Chancellor Sir Michael Thompson and the Registrar David the acknowledgement that objects can uniquely loosen through the dedication of a small number of determined Holmes, a survey was made of the miscellaneous groups the professor’s tongue and widen the understanding academics including Professors Janusz Kolbuszewski of pictures, sculpture, artefacts, and ceremonial objects of students. Research priorities change over time and and Anthony Lewis, Angus Skene and Kenneth Garlick. that were to be found in and around the University. it follows that the value of a particular collection to Together they laid the foundations of the collections with academics and students will correspondingly fluctuate. -

Exhibitions and Events Guide

Exhibitions / Events June – September 2018 ikon-gallery.org Free entry 1 2 Ikon presents a solo exhibition by Belgian-born, drama of such an action is compelling; the jolting A number of small landscapes, oils on canvas, Francis Alÿs Mexico-based artist Francis Alÿs, curated by Marie imagery, the sound of the wind in and around the literally spell out what is on the artist’s mind, being Muracciole. tornadoes compounds a sense of danger, something inscribed with Spanish and English words such as the artist is prepared to endure before arriving at Turbulencia (Turbulence), Resistencia (Resistance) Knots’n Dust Organised by the Beirut Art Center, the exhibition monochromes of dust, abstracting him from the and Puro Desorden (Pure Disorder). These refer to is an outcome of Alÿs’ long-term interest in outside world. observations on current affairs as much as personal Exhibition current affairs in the Middle East and his frequent experience, and it is significant that the artist has 20 June – 9 September 2018 travelling to that part of the world, especially Iraq Nearby is an installation of hundreds of drawings, spent much time recently in the turbulent Middle First Floor Galleries and Afghanistan. Featuring new work in a mix of suspended in space at the centre of the gallery, East, especially Iraq and Afghanistan. animation, drawing, film, painting and photography, leading on to Exodus 3:14 (2013–2017), a projected the exhibition is a reflection on the notion of drawn animation shown in an endless loop, As a commission for the Beirut Art Center, Alÿs turbulence, from simple instability to chaos, from a portraying a young woman tying a knot in her long made a number of photographs that are now 1 Francis Alÿs meteorological phenomenon to bigger geopolitical hair which then undoes itself. -

Exhibition Guide

Was Good at Latin) and close friend Benjamin Britten (Season in Hell). A later series shown in the central room, from 1986, features Aboriginal subjects. It Exhibition Guide signals a return to a theme, evident very early on in Nolan’s artistic career, of the unresolved relationship between indigenous Sidney Nolan Australians and European settlers. Then, 10 June – 3 September 2017 in the final room, more overtly there are the paintings that take as their subject the Sheela Gowda Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths 16 June – 3 September 2017 in Custody (1987–1991), set up to investigate the causes of deaths of Aboriginal people John Stezaker while held in Australian jails in response to 16 June – 3 September 2017 a growing public concern. These are very vivid paintings, deriving dramatic impact and poignancy from their resemblance on Sidney Nolan one hand to spray-painted graffiti, with transgression implied, and on the other to Sidney Nolan (1917–1992) was one of the most Aboriginal cave paintings. important Australian artists of the twentieth century and he lived the last fourteen years of The 1980s was the decade of post- his life on the Welsh-Midlands border. To mark modernism, of appropriation, a revival of the centenary of his birth, in collaboration figuration and, incidentally a proliferation with the Sidney Nolan Trust, Ikon brings to of graffiti art, but it would be a mistake to light a selection of extraordinary paintings by cast Nolan simply in some trans-avant- Nolan from the 1980s. garde light, because he never stopped painting expressionistically and being open Sidney Nolan is best known for his paintings to influence.