View/Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Book of St. Louis Nostalgia Authors: Bill Nunes, Lonnie Tettaton, and Dave Lossos

Big Book of St. Louis Nostalgia Authors: Bill Nunes, Lonnie Tettaton, and Dave Lossos Index by Dave Lossos ([email protected]) 10 Cent Radio Treasures. ............................................................................................ 8 1811 New Madrid Quake. ....................................................................................... 227 1896 Cyclone. ................................................................................................... 55, 144 1904 St. Louis World's Fair. ...................................................................................... 66 1925 Tornado.......................................................................................................... 191 1960s St. Louis Restaurants....................................................................................... 50 66 Park-In Theater. ................................................................................................... 33 7-Up Soda............................................................................................................... 214 Absorbene Mfg. Co.. ........................................................................................ 269, 281 Ace Cab Company..................................................................................................... 90 Actors and Actresses. .............................................................................................. 229 Admiral - Tribute to the SS Admiral. ........................................................................ -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

The Mill Creek Hundred History Blog: the Greenbank Mill and the Philips

0 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In The Mill Creek Hundred History Blog Celebrating The History and Historical Sites of Mill Creek Hundred, in the Heart Of New Castle County, Delaware Home Index of Topics Map of Historic Sites Cemetery Pictures MCH History Forum Nostalgia Forum About Wednesday, February 20, 2013 The Greenbank Mill and the Philips House -- Part 1 The power of the many streams and creeks of Mill Creek Hundred has been harnessed for almost 340 years now, as the water flows from the Piedmont down to the sea. There have been literally dozens of sites throughout the hundred where waterwheels once turned, but today only one Greenbank Mill in the 1960's, before the fire Mill Creek Hundred 1868 remains. Nestled on the west bank of Red Clay Creek, the Search This Blog Greenbank Mill stands as a living testament to the nearly three and a half century tradition of water-powered milling in MCH. The millseat at Search Greenbank is special to the story of MCH for several reasons -- it was one of the first harnessed here, it's the longest-serving, and it's the only one still in operable condition. The fact that it now serves as a teaching tool Show Your Appreciation for the MCHHB With PDFmyURL anyone can convert entire websites to PDF! only makes it more special, at least in my eyes. The early history of the millseat at Greenbank is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside....Ok, it's not quite that bad, but the actual facts are far Recent Comments from clear. -

MD Rail Plan

Maryland State Rail Plan Project Update Presented to: Baltimore Regional Transportation Board Freight Movement Task Force Presented by: Harry Romano, MDOT OFM Date: March 25, 2021 Agenda » Introduction » Background, Plan Outline, Schedule » Vision and Goals » Review Project Types » Coordination and Outreach » Next Steps 2 Real-Time Feedback Using Poll Everywhere 3 Poll Everywhere #1: In one word, what do you see as the greatest opportunity for rail in Maryland? Poll Everywhere #2: In one word, what concept should not be left out of the Maryland State Rail Plan? 5 6 Background, Plan Outline, and Schedule 7 Why Is Maryland Updating the State Rail Plan? » Federal requirement per the 2008 Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act (PRIIA), affirmed in federal surface transportation bills, 4-year update per the FAST Act » Positions the state and rail stakeholders for federal funding » Outlines public and private investments and policies needed to ensure the efficient, safe, and sustainable movement of freight and passenger by rail 8 What Does a State Rail Plan Cover? Commuter Rail Freight Rail Intercity Passenger Rail 9 Background – Maryland’s Freight Rail Network Total Miles Operated Miles Owned, Miles Owned, Not Railroad Miles Leased (Except Trackage Rights Operated Operated Trackage Rights) Class I Railroads CSX Transportation 5 455 7 460 86 Norfolk Southern Railway 59 42 59 200 Total Class I Railroads 5 514 49 519 286 Class II Railroads Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad 25 Class III Railroads Canton Railroad 16 16 Georges Creek Railway -

E. Heritage Health Index Participants

The Heritage Health Index Report E1 Appendix E—Heritage Health Index Participants* Alabama Morgan County Alabama Archives Air University Library National Voting Rights Museum Alabama Department of Archives and History Natural History Collections, University of South Alabama Supreme Court and State Law Library Alabama Alabama’s Constitution Village North Alabama Railroad Museum Aliceville Museum Inc. Palisades Park American Truck Historical Society Pelham Public Library Archaeological Resource Laboratory, Jacksonville Pond Spring–General Joseph Wheeler House State University Ruffner Mountain Nature Center Archaeology Laboratory, Auburn University Mont- South University Library gomery State Black Archives Research Center and Athens State University Library Museum Autauga-Prattville Public Library Troy State University Library Bay Minette Public Library Birmingham Botanical Society, Inc. Alaska Birmingham Public Library Alaska Division of Archives Bridgeport Public Library Alaska Historical Society Carrollton Public Library Alaska Native Language Center Center for Archaeological Studies, University of Alaska State Council on the Arts South Alabama Alaska State Museums Dauphin Island Sea Lab Estuarium Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository Depot Museum, Inc. Anchorage Museum of History and Art Dismals Canyon Bethel Broadcasting, Inc. Earle A. Rainwater Memorial Library Copper Valley Historical Society Elton B. Stephens Library Elmendorf Air Force Base Museum Fendall Hall Herbarium, U.S. Department of Agriculture For- Freeman Cabin/Blountsville Historical Society est Service, Alaska Region Gaineswood Mansion Herbarium, University of Alaska Fairbanks Hale County Public Library Herbarium, University of Alaska Juneau Herbarium, Troy State University Historical Collections, Alaska State Library Herbarium, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa Hoonah Cultural Center Historical Collections, Lister Hill Library of Katmai National Park and Preserve Health Sciences Kenai Peninsula College Library Huntington Botanical Garden Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park J. -

Mayor V. Fairfield Improvement Company

Mayor v. Fairfield Improvement Company: The Public’s Apprehension to Accept Nineteenth Century Medical Advancements Ryan Wiggins Daniella Einik Baltimore Environmental History December 21, 2009 I. INTRODUCTION On November 20, 1895, Alcaeus Hooper stood before a crowd of politicians, family, friends, and supporters in Baltimore’s city hall. “We feel that the election just held is more than an unusual one,” Hooper bellowed, “[t]hat it has amounted to a revolution, and it demands a change in the personnel of the many offices under the control of the municipality. The revolution calls louder, however, for a change in the methods of administration.”1 Hooper was about to be inaugurated as Baltimore’s first Republican mayor in a generation. He was a reform candidate who had united Independent Democrats, Republicans, and the Reform League against Isaac Freeman Rasin’s Democratic political machine. Political bosses had dominated Baltimore and Maryland politics since the 1870s, acting as middlemen between the city’s powerful business tycoons and a governmental structure that they largely controlled. In 1895, reform won overwhelmingly at the state and city level.2 Many people were eager for a change they could believe in. In spite of initial gains, including election reform and moves towards greater municipal efficiency, optimism for progressive change in the Hooper administration quickly cooled amongst the Baltimore elite. Hooper refused to acknowledge patronage issues, and in spite of some public support, had considerable trouble with the city council.3 In early 1897, a dispute over the school board set Hooper and the city council against each other in the Maryland Court of Appeals. -

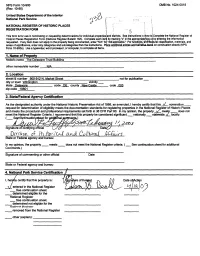

1. Name of Property 3. State/Federal

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM |i D ! ' This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties! and districts. See instructions in l|iow to] Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriatefb.pg oj by entering the information requested, if any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" foi' "rtot applicable." For functtons^afcmeqtural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. PI ice additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name The Delaware Trust Building other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 900-912 N. Market Street not for publication _ city or town Wilmington ____________ vicinity _ state Delaware____ code DE county Newcastle____ code 003 zip code 19801 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this \/ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property \S meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally _ statewide / locally. -

Railroads of Landenberg

Winter 2014 Issue Railroads of Landenberg By Chris Black It was 12:05 on October 19, 1872 when the first train on the Wilmington and Western Railroad reached its final destination in the village of Landenberg. A large crowd of the Townspeople gathered, dressed in their best outfits, to cheer on the dignitaries, public officials, and the press as they stepped down from the train. The procession marched up the Landenberg hill to beat the beat of Wilmington’s Independent Cornet Band. When they reached the home of Charles Weiler, the general superintendent of the Landenberger Mills, there were speeches and a lavish reception. Joshua T. Heald, President of the Wilmington and Western Railroad, spoke not only of how proud he was of the work up to Landenberg, but of an optimistic future for this small railroad as it continued west. The Wilmington and Western Railroad was chartered in 1867 by a Corporate Board with the hope it would travel to Landenberg, The village of Landenberg as seen in about 1905 from the vantage point of the Pomeroy and Newark railroad track crossing over Landenber road. A newly rebuilt Lancaster, York, Pittsburgh and (1898) road bridge crossing the White Clay Creek connected Landenberg's business eventually far to the west in the district with residential homes on the eatern hill rising from it. The railroad tracks ran United States. However at its along this side of the creek. (Courtesy NGTHC.) zenith, the railroad stretched for only 19 miles. These 19 miles were from Wilmington to Landenberg, with seven stops along the way. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Downtown Wilmington Commercial Historic District Other names/site number: Name of related multiple property listing: (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: City or town: Wilmington State: DE County: New Castle Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: ___national ___statewide _ X_ local Applicable National Register Criteria: _X _A ___B _X _C ___D Signature of certifying official/Title: Date ______________________________________________ State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government 1 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10900 OMB No. -

Maryland Department of Business and Economic Development

Rail Page 1 of 6 Citizen Alerts Maryland.gov Online Services State Agencies Phone Directory CONTACT U S | HOME Search BUSINESS I N M ARYLAND FACTS & F IGURES BUILDINGS & S ITES REGIONS & C OUNTIES BUSINESS S ERVICES PRESS R OOM ABOUT DBED Home > Facts & Figures > Transportation Rail Maps Maryland's freight rail system uses the latest equipment and technology to Demographics meet shipper demands for fast, efficient rail service to all U.S. interior Business Community points, Canada, and Mexico. Workforce Profile Transportation Long haul freight services are provided by two Class I rail carriers, CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern . These two carriers also connect with Utilities Canadian Pacific and Canadian National Railways, which serve Canada and Taxes extreme northern points. Education Quality of Life A wide array of services is provided to the Port of Baltimore , including intermodal U.S. inland locations. Packaged goods and bulk rail commodity I'm looking for... transfers between truck, rail, and extensive automobile loading and distribution operations exist across the state. In addition to Class I rail carriers, Maryland also has a connecting network of short line railroads which provide service from Western Maryland to the Delmarva Peninsula. Maryland Rankings Maryland's Railways Comparative Data Tables CSX Transportation (CSXT) CSXT's unique combination of trains, trucks, ships, barges, intermodal services, and technology and logistics support helps companies deliver raw materials to support manufacturing and move finished product to the rest of the world. These corridors extend single-line service between the Northeastern and most major markets in the South and Ohio Valley. Significant potential exists for diverting traffic from trucks to rail along the entire east coast, which has a favorable impact upon highway congestion and air quality. -

A. Magruder's and Beall's

Reddall v. Bryan and the Role of State Law in Federal Eminent Domain Jurisprudence Shannon Frede Article 2015 Keywords: Washington Aqueduct, City of Washington, Montgomery Meigs, Condemnation, Army Corps of Engineers, Montgomery County, The Potomac River, John S. Tyson Abstract: Prior to 1875, the standard federal takings procedure had been for state governments to condemn property on behalf of the federal government. As a result, the majority of interpretative work in the early history of eminent domain jurisprudence was undertaken by state courts. In 1853, the Maryland General Assembly granted the United States Government the power to condemn land in Maryland for an aqueduct across the Potomac to supply water to two District cities. In Reddall v. Bryan, the Maryland Court of Appeals upheld the aqueduct supplying the city of Washington with water as a public use. The Court reasoned that any constitutional use by the United States was a public use of every part of the United States—and therefore in each one of the states. Securing an adequate water supply for the Capital of the Government of the United States was in the public interest, particularly at a time when public records were vulnerable to the threat of fire. States continued to condemn land for federal projects, even as the joint takings scheme became complicated, and was no more convenient than a direct federal taking, as the case of Reddall v. Bryan demonstrates. The Federal government did not assert its power of eminent domain in its own name in its own courts until 1875. Discipline: Takings Jurisprudence, United States History, Riparian Property Rights 1 Contents I. -

Final Report White Clay Creek Wild And

Final Report White Clay Creek Wild and Scenic River Shad Restoration Project (Removal of Byrnes Dam No. 1) New Castle County Wilmington, Delaware April 1, 2015 Prepared for: American Rivers Washington, D.C. U. S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Annapolis, Md. Prepared by: Gerald J. Kauffman, Director University of Delaware Water Resources Agency Newark, Del. 0 April 1, 2015 Serena McClain American Rivers 1101 14th Street NW, Suite 1400 Washington, DC 20005 Laura Craig American Rivers P.O. Box 14986 Philadelphia, PA 19149 Re: American Rivers/NOAA White Clay Creek Removal of Byrnes Dam No. 1 Dear Serena and Laura: Enclosed is the final report under the terms of our American Rivers/NOAA grant that documents the removal of White Clay Creek Byrnes Dam No. 1 in December 2014: • Final report (final progress report) • Match letter and documentation • Final budget and copies of invoices (contractor)) documenting expenditure of the award • Final copies of other materials relevant to funded phase (feasibility report, appendices) We look forward to scheduling a public event with American Rivers and NOAA during the spring 2015 spawning runs to commemorate the reopening of the White Clay Creek National Wild and Scenic River to fish passage and mark the installation of the creek-side interpretative sign. Thank you for of your assistance from American Rivers and NOAA during this first-ever dam removal for fish passage in the State of Delaware. Warmly, Gerald J. Kauffman Gerald J. Kauffman, Director Water Resources Agency University of Delaware 1 American Rivers/NOAA Community-based Restoration Program (Final Progress Report April 1, 2015) Project Title White Clay Creek Wild & Scenic River Shad Restoration Project (Delaware) Removal of Dam No.