Religionspädagogische Lexikon Im Internet (Wirelex)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November-December 2011 Annual Subscription

November-December 2011 Annual Subscription ` 60/- SWAMISHRI IN MUMBAI, 11 October 2011 Above: On the auspicious occasion of Sharad Purnima, the birthday of Aksharbrahman Gunatitanand Swami, Swamishri offers heartfelt prayers. Top Right and Left: Swamishri is also honoured and engages in joyous dialogue with the devotees. November-December 2011 Akshar Purushottam Maharaj Vol. 34 No. 9 CONTENTS 4 First Word 5 Shri Hari Reveals His Purpose on Earth 8 Adhyãy 2: Brãhmi Sthiti Yoga; Yoga Is Dharma, Part 7 14 12 New Jersey Akshardham Shilanyas Ceremony, Mumbai 14 Akshardham Mahamandir Shilanyas Mahotsav, Robbinsville, New Jersey (USA) 16 Hindu Festivals 18 Narsinh Mehta: A Doyen Among Saint-Poets 23 Aalsi Ganchi and Alibhai 26 Shaucham 16 30 Satsang Exams: Basis of True Understanding 34 Sahajanand Swami Re, Na Pragatat à Same Re… 37 Music and Bhakti 39 Obesity: Management and Prevention, Part 2 42 Hinduism, An Introduction: Reviews 45 Pramukh Swami Maharaj’s Vicharan 49 Living with Swamishri 53 New BAPS Swaminarayan Mandir Opens in 18 Leicester 54 BAPS News In April 1978 Pramukh Swami Maharaj inspired and inaugurated the first issue of Swaminarayan Bliss in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. The bi-monthly magazine serves to enlighten BAPS youths, seniors and well-wishers about the glory of Bhagwan Swaminarayan, the Akshar-Purushottam philosophy and the Gunatit guru parampara. It also seeks to inspire the universal values and traditions of Hinduism to pursue a happy and peaceful life by serving God and humankind. Founder: HDH Pramukh Swami Maharaj SUBSCRIPTION RATES Editor: Sadhu Swayamprakashdas Outside India (By Air Mail) India Contributors: Sadhu Vivekjivandas, Sadhu Amrutvijaydas Rupees Pounds US Dollars Rupees Designer: Sadhu Shrijiswarupdas 1 Year 630 9 14 60 Published & Printed by: Swaminarayan Aksharpith, Shahibaug, 2 Years 1300 18 28 110 u Ahmedabad - 380004. -

School Parking Compliance

Highways Committee 7 February, 2013 Report from the Director of Environment & Neighbourhood Services For information Wards Affected: All School parking compliance 1.0 Summary 1.1 This report provides the Committee with an interim update of the results of parking compliance surveys at schools, an examination of potential equalities issues, and recommendations for future prioritisation. 2.0 Recommendations 2.1 That the Committee notes progress towards the completion of a more methodical approach to improving parking behaviour in the vicinity of schools during the school run’, through the potential for reprioritising of parking enforcement and reprioritising school travel plan development and support. 2.2 To instruct the Head of Safer Streets to complete the parking compliance survey for all schools and together with the Head of Transportation to bring forward proposals for focussing enforcement and modality shift resources in respect of schools with greatest levels of parking non-compliance. 3.0 Detail 3.1 The 20 March 2012 Highways Committee considered a petition from some parents at Al Sadiq and Al Zahra Schools in Chevening Road with concerns about an excessive number of Civil Enforcement Officers and the CCTV vehicle outside the schools as this was intimidating and a form of racial discrimination. A spokesman for the Islamic Human Rights Commission claimed that no other Brent school had that level of parking enforcement, and urged the Council to relax enforcement. Highways Committee 7 February, 2013 Version 1 3.2 The 17 July 2012 Highways Committee considered a petition from some parents at Islamia Primary School 129 Salusbury Road regarding concerns about parking enforcement outside the school and the challenge parents faced on a daily basis to find parking in order to get their children to school. -

Tokyngton Wards Are Major Destinations in Themselves in Addition to Being Residential Areas

ELECTORAL REVIEW OF THE LONDON BOROUGH OF BRENT WARDING PATTERN SUBMISSION BY THE BRENT CONSERVATIVE GROUP RESPONSE TO THE LGBCE CONSULTATION NOVEMBER 2018 1 | P a g e Introduction Why Brent? During the current London Government Boundary Commission Executive (LGBCE) review process, it has become clear to us that since the previous review in 2000, warding levels have developed out of balance. Brent Council meets the Commission’s criteria for electoral inequality with 7 wards having a variance outside 10%. The outliers are Brondesbury Park at -16% and Tokyngton at 28%. Electoral review process The electoral review will have two distinct parts: Council size – The Brent conservative group welcomes to reduce the number of councillors to 57 from current 63. We appreciate that this will require some existing wards to be redrawn, and recognise that this will represent an opportunity to examine whether the existing boundaries are an appropriate reflection of how Brent has developed since 2000. In addition, the establishment of new developments such as South Kilburn Regeneration, Wembley Regeneration, Alperton and Burnt Oak and Colindale area. Ward boundaries – The Commission will re-draw ward boundaries so that they meet their statutory criteria. Should the Commission require any further detail on our scheme we would be very happy to pass on additional information or to arrange a meeting with Commission members or officers to run through the proposals. 2 | P a g e Interests & identities of local communities The Commission will be looking for evidence on a range of issues to support our reasoning. The best evidence for community identity is normally a combination of factual information such as the existence of communication links, facilities and organisations along with an explanation of how local people use those facilities. -

MGLA260719-8697 Date

Our ref: MGLA260719-8697 Date: 22 August 2018 Dear Thank you for your request for information which the GLA received on 26 June 2019. Your request has been dealt with under the Environmental Information Regulations (EIR) 2004. Our response to your request is as follows: 1. Please provide the precise number and list of locations/names of primary and secondary schools in London where air pollution breaches legal limit, according to your most recent data (I believe the same metric has been used across the years, of annual mean limit of 40ug/m3 NO2, but please clarify). If you are able to provide more recent data without breaching the s12 time limit please do. If not, please provide underlying data from May 2018 (see below). Please provide as a spreadsheet with school name, pollution level, and any location information such as borough. This data is available on the London datastore. The most recent available data is from the London Atmospheric Emission Inventory (LAEI) 2016 and was published in April 2019. The data used for the 2018 report is LAEI 2013. Please find attached a list and a summary of all Educational Establishments in London and NO2 levels based on both the LAEI 2013 update and LAEI 2016. The list has been taken from the register of educational establishments in England and Wales, maintained by the Department for Education, and provides information on establishments providing compulsory, higher and further education. It was downloaded on 21/03/2019, just before the release of the LAEI 2016. The attached spreadsheet has recently been published as part of the LAEI 2016 stats on Datastore here. -

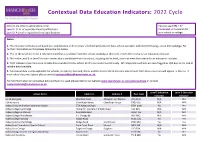

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

1 Bedroom Flat to Rent in DOLLIS HILL £280Pw

1 Bedroom Flat To Rent In DOLLIS HILL £280pw (£1214 pcm) 1 Bedroom Flat To Rent In DOLLIS HILL£ 280pw (£1214 pcm) <p>**VIDEO VIEWING AVAILABLE**</p><p>An excellent one double bedroom apartment that has been completed to a modern standard throughout, a short walk from DOLLIS HILL tube (JUBILEE LINE) and good bus connections. The property has a modern kitchen and fully tiled bathroom with wood flooring throughout and bright neutral decor. The property is double glazed throughout and has a new combi boiler system making a very efficient and cost efficient flat. There are a good range of local amenities within a short walk away. Quick viewings are highly recommended.</p> E.P.C. RATING: C Property Features . Wood Floors . Washing Machine . Separate kitchen . Close to local amenities . Close to Tube . Fantastic Transport Links . Gas Central Heating . Double Glazed . Good decorative order . Tiled bathroom . Zone 3 Place of Interest Locally College of North West London - 0.23 miles. Capital City Academy - 0.89 miles. The Swaminarayan School - 0.95 miles. Hampstead School - 1.35 miles. Preston Manor High School - 2.35 miles. St Augustines C Of E Primary School - 2.37 miles. Sion Manning Secondary School - 2.44 miles. University College School (Senior School) - 2.47 miles. Hendon School - 2.48 miles. JFS - 2.7 miles. Paddington Academy - 2.74 miles. The American School in London - 2.92 miles. Kingsbury High School - 3.01 miles. Claremont High School - 3.24 miles. The Ellen Wilkinson School for Girls - 3.27 miles. 1 Bedroom Flat To Rent In DOLLIS HILL£ 280pw (£1214 pcm) 22 West Hampstead Manager:Jamie Black Office Hours: Mews Email:[email protected] Mon-Fri 9.00am-7.00pm West Hampstead Tel:020 7328 5000 Sat-10am-2.00pm London (Please call beforehand) NW6 3BB Admin:Erika Szabo Email:[email protected] We aim to make our particulars both accurate and reliable. -

Eligible If Taken A-Levels at This School (Y/N)

Eligible if taken GCSEs Eligible if taken A-levels School Postcode at this School (Y/N) at this School (Y/N) 16-19 Abingdon 9314127 N/A Yes 3 Dimensions TA20 3AJ No N/A Abacus College OX3 9AX No No Abbey College Cambridge CB1 2JB No No Abbey College in Malvern WR14 4JF No No Abbey College Manchester M2 4WG No No Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG No Yes Abbey Court Foundation Special School ME2 3SP No N/A Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN No No Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA No No Abbey Hill Academy TS19 8BU Yes N/A Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST3 5PR Yes N/A Abbey Park School SN25 2ND Yes N/A Abbey School S61 2RA Yes N/A Abbeyfield School SN15 3XB No Yes Abbeyfield School NN4 8BU Yes Yes Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Yes Yes Abbot Beyne School DE15 0JL Yes Yes Abbots Bromley School WS15 3BW No No Abbot's Hill School HP3 8RP No N/A Abbot's Lea School L25 6EE Yes N/A Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Yes Yes Abbotsholme School ST14 5BS No No Abbs Cross Academy and Arts College RM12 4YB No N/A Abingdon and Witney College OX14 1GG N/A Yes Abingdon School OX14 1DE No No Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Yes Yes Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Yes N/A Abraham Moss Community School M8 5UF Yes N/A Abrar Academy PR1 1NA No No Abu Bakr Boys School WS2 7AN No N/A Abu Bakr Girls School WS1 4JJ No N/A Academy 360 SR4 9BA Yes N/A Academy@Worden PR25 1QX Yes N/A Access School SY4 3EW No N/A Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Yes Yes Accrington and Rossendale College BB5 2AW N/A Yes Accrington St Christopher's Church of England High School -

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible If Taken GCSE's at This

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible if taken GCSE's at this AUCL Eligible if taken A-levels at school this school City of London School for Girls EC2Y 8BB No No City of London School EC4V 3AL No No Haverstock School NW3 2BQ Yes Yes Parliament Hill School NW5 1RL No Yes Regent High School NW1 1RX Yes Yes Hampstead School NW2 3RT Yes Yes Acland Burghley School NW5 1UJ No Yes The Camden School for Girls NW5 2DB No No Maria Fidelis Catholic School FCJ NW1 1LY Yes Yes William Ellis School NW5 1RN Yes Yes La Sainte Union Catholic Secondary NW5 1RP No Yes School St Margaret's School NW3 7SR No No University College School NW3 6XH No No North Bridge House Senior School NW3 5UD No No South Hampstead High School NW3 5SS No No Fine Arts College NW3 4YD No No Camden Centre for Learning (CCfL) NW1 8DP Yes No Special School Swiss Cottage School - Development NW8 6HX No No & Research Centre Saint Mary Magdalene Church of SE18 5PW No No England All Through School Eltham Hill School SE9 5EE No Yes Plumstead Manor School SE18 1QF Yes Yes Thomas Tallis School SE3 9PX No Yes The John Roan School SE3 7QR Yes Yes St Ursula's Convent School SE10 8HN No No Riverston School SE12 8UF No No Colfe's School SE12 8AW No No Moatbridge School SE9 5LX Yes No Haggerston School E2 8LS Yes Yes Stoke Newington School and Sixth N16 9EX No No Form Our Lady's Catholic High School N16 5AF No Yes The Urswick School - A Church of E9 6NR Yes Yes England Secondary School Cardinal Pole Catholic School E9 6LG No No Yesodey Hatorah School N16 5AE No No Bnois Jerusalem Girls School N16 -

Hot Food Takeaways in Brent Policy Evidence Base

Hot Food Takeaways in Brent Policy Evidence Base 1.0 Introduction 1.1 The purpose of this report is to provide an evidence base for the hot food takeaway policy in the emerging Development Management Development Plan Document (DMDPD). This report summarises the policy context and evidence which have informed the council’s decision to regulate takeaways through the planning system. 2.0 Planning Policy Context 2.1 The National Planning Policy Framework (2012) emphasises that the purpose of the planning system is to contribute towards sustainable development. One of the three dimensions in achieving sustainable development is for the planning system to perform a social role by supporting ‘strong, vibrant and healthy communities.’1 Consequently one of the core planning principles is to ‘take account of and support local strategies to improve health, social and cultural wellbeing for all and deliver sufficient community and cultural facilities and services to meet local needs.’ 2 In relation to plan making, local authorities should have an up to date and relevant evidence base for the Local Plan. To develop this evidence base local planning authorities are to work with public health organisations to understand and take account of the health status and needs of the local population and information about relevant barriers to improving health and wellbeing. 2.2 The important role the planning system has to play in improving health and wellbeing of Londoners has been recognised for some time. In 2006 the London Development Authority published The Mayor’s Food Strategy which includes the strategic objective to improve Londoner’s health and reduce health inequalities via the food they eat. -

School and College (Key Stage 5)

School and College (Key Stage 5) Performance Tables 2010 Lonon West FE3 Introduction These tables provide information on the London West achievement and attainment of students of sixth-form age in local secondary schools and FE3 further education sector colleges. They also show how these results compare with other Local Authorities covered: schools and colleges in the area and in England rent as a whole. aling The tables list, in alphabetical order and sub- divided by the local authority (LA), the further Hammersmithandulham education sector colleges, state funded Harrow secondary schools and independent schools in the regional area with students of sixth-form Hillingdon age. Special schools that have chosen to be Hounslow included are also listed, and a inal section lists any sixth-form centres or consortia that operate in the area. The Performance Tables website www. education.gov.uk/performancetables enables you to sort schools and colleges in ran order under each performance indicator to search for types of schools and download underlying data. Each entry gives information about the attainment of students at the end of study in general and applied A and AS level examinations and equivalent level 3 qualiication (otherwise referred to as the end of ‘Key Stage 5’). The information in these tables only provides part of the picture of the work done in schools and colleges. For example, colleges often provide for a wider range of student needs and include adults as well as young people Local authorities, through their Connexions among their students. The tables should be services, Connexions Direct and Directgov considered alongside other important sources Young People websites will also be an important of information such as Ofsted reports and school source of information and advice for young and college prospectuses. -

2 Bedroom Flat to Rent in WILLESDEN GREEN

2 Bedroom Flat Rent In WILLESDEN GREEN£ 350pw (£1516 pcm) 2 Bedroom Flat Rent In WILLESDEN GREEN£ 350pw (£1516 pcm) <p>We are delighted to offer this bright and spacious two double bedroom flat located seconds away from Willesden Green station. The property features a large separate living room, two good size double bedrooms and modern kitchen and bathroom. Further benefits are gas central heating, double glazed windows and bathroom with bath/shower. The property is located within short walk away from all local amenities and transport links.</p> E.P.C. RATING: D Property Features . Separate kitchen . Close to local amenities . Close to Tube . Fantastic Transport Links . Central Heating . Spacious Living Room . Beautiful tree lined street Place of Interest Locally Saint Mary Magdalen's Roman Catholic Junior School - 0.03 miles. Queens Park Community School - 0.7 miles. Capital City Academy - 0.71 miles. Convent of Jesus and Mary Language College - 1.02 miles. Princess Frederica Church of England Primary School - 1.06 miles. Islamia Primary School - 1.07 miles. John Kelly Boys' Technology College - 1.15 miles. The Swaminarayan School - 1.36 miles. A Home To Grow Childminders - 1.46 miles. The Educational and Cultural Center I.R. Iran - 1.75 miles. St Margaret's School - 1.77 miles. Oakington Manor Primary School - 1.84 miles. Saint Charles Roman Catholic Primary School - 1.94 miles. Paddington Academy - 2.22 miles. South Hampstead High School - 2.26 miles. 2 Bedroom Flat Rent In WILLESDEN GREEN£ 350pw (£1516 pcm) 22 West Hampstead Manager:Jamie Black Office Hours: Mews Email:[email protected] Mon-Fri 9.00am-7.00pm West Hampstead Tel:020 7328 5000 Sat-10am-2.00pm London (Please call beforehand) NW6 3BB Admin:Erika Szabo Email:[email protected] We aim to make our particulars both accurate and reliable. -

5742Tbm81 Large Print

The Brent Magazine Issue no.157 Autumn 2018 Free for people who live and work in Brent This is the large print edition of The Brent Magazine produced for people with visual impairment. If you have comments on how it could be improved, or if you would like a copy on audio tape please contact 020 8937 1062 . www.Brent.gov.uk Advertisement • Brahmaswarup Pramuk Swami Maharaj The UK’s In this issue • Pragat Brahmaswarup Mahant Swami Maharaj Largest Hindu • Shri Akshar Purushottam Maharaj New Year NEWS 6 GETTING READY FOR A round-up of the UNIVERSAL CREDIT 41 Celebrations latest news in Brent Universal Credit is coming HALF WAY THERE 22 to Brent soon An update on the QUESTION TIME RETURNS 43 Diwali & Annakut South Kilburn regeneration The panel event is back CELEBRATIONS HELPING YOU INTO WORK 24 OUR SURVEY SAYS… 45 Find out about some of the The results from our BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir apprenticeships on offer residents survey – LONDON – MENTAL HEALTH MATTERS 27 YOU ARE THE CHAMPIONS 47 Diwali Fiona Heffernan discusses A new scheme to help renters her mental health journey know their rights WEDNESDAY 7 NOVEMBER 2018 Diwali Darshan: 9.00am to 8.00pm MUSIC TO YOUR EARS 31 A HOME FROM HOME 48 Chopda pujan: 5.30pm to 7.00pm – BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Brent Makes Music on stage at Jamal’s story from Syria to Brent Fireworks display: 8.15pm to 8.45pm – The Swaminarayan School The SSE Arena in Wembley BRENT’S NEW FESTIVAL OF LOVE 33 FUNERAL SERVICE 49 Hindu New Year Annakut Celebrating the life of Brent Council’s low-cost Quamari Serunkuma-Barnes funeral service is here THURSDAY 8 NOVEMBER 2018 Annakut Darshan: 12.00 noon to 9.00pm GCSE AND A’ LEVEL RESULTS 35 ARTS AND CULTURE 51 Half-Hourly Arti: Until 9.00pm The results are in! Theatre, music, events PARENT POWER 40 and more Hot delicious snacks will be available on both days from food stalls Two families on the parenting WHAT’S ON 59 Please kindly note: For security reasons, bags and cameras will not be support programmes Classes, fitness and allowed into the Mandir complex.