Generic Misalignment Aberration Patterns in Wide-Field Telescopes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wavefront Sensing for Adaptive Optics MARCOS VAN DAM & RICHARD CLARE W.M

Wavefront sensing for adaptive optics MARCOS VAN DAM & RICHARD CLARE W.M. Keck Observatory Acknowledgments Wilson Mizner : "If you steal from one author it's plagiarism; if you steal from many it's research." Thanks to: Richard Lane, Lisa Poyneer, Gary Chanan, Jerry Nelson Outline Wavefront sensing Shack-Hartmann Pyramid Curvature Phase retrieval Gerchberg-Saxton algorithm Phase diversity Properties of a wave-front sensor Localization: the measurements should relate to a region of the aperture. Linearization: want a linear relationship between the wave-front and the intensity measurements. Broadband: the sensor should operate over a wide range of wavelengths. => Geometric Optics regime BUT: Very suboptimal (see talk by GUYON on Friday) Effect of the wave-front slope A slope in the wave-front causes an incoming photon to be displaced by x = zWx There is a linear relationship between the mean slope of the wavefront and the displacement of an image Wavelength-independent W(x) z x Shack-Hartmann The aperture is subdivided using a lenslet array. Spots are formed underneath each lenslet. The displacement of the spot is proportional to the wave-front slope. Shack-Hartmann spots 45-degree astigmatism Typical vision science WFS Lenslets CCD Many pixels per subaperture Typical Astronomy WFS Former Keck AO WFS sensor 21 pixels 2 mm 3x3 pixels/subap 200 μ lenslets CCD relay lens 3.15 reduction Centroiding The performance of the Shack-Hartmann sensor depends on how well the displacement of the spot is estimated. The displacement is usually estimated using the centroid (center-of-mass) estimator. x I(x, y) y I(x, y) s = sy = x I(x, y) I(x, y) This is the optimal estimator for the case where the spot is Gaussian distributed and the noise is Poisson. -

Lab #5 Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensor

EELE 482 Lab #5 Lab #5 Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensor (1 week) Contents: 1. Summary of Measurements 2 2. New Equipment and Background Information 2 3. Beam Characterization of the HeNe Laser 4 4. Maximum wavefront tilt 4 5. Spatially Filtered Beam 4 6. References 4 Shack-Hartmann Page 1 last edited 10/5/18 EELE 482 Lab #5 1. Summary of Measurements HeNe Laser Beam Characterization 1. Use the WFS to measure both beam radius w and wavefront radius R at several locations along the beam from the HeNe laser. Is the beam well described by the simple Gaussian beam model we have assumed? How do the WFS measurements compare to the chopper measurements made previously? Characterization of WFS maximum sensible wavefront gradient 2. Tilt the wavefront sensor with respect to the HeNe beam while monitoring the measured wavefront tilt. Determine the angle beyond which which the data is no longer valid. Investigation of wavefront quality after spatial filtering and collimation with various lenses 3. Use a single-mode fiber as a spatial filter. Characterize the beam emerging from the fiber for wavefront quality, and then measure the wavefront after collimation using a PCX lens and a doublet. Quantify the aberrations of these lenses. 2. New Equipment and Background Information 1. Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensor (WFS) The WFS uses an array of microlenses in front of a CMOS camera, with the camera sensor located at the back focal plane of the microlenses. Locally, the input beam will look like a portion of a plane wave across the small aperture of the microlens, and the beam will come to a focus on the camera with the center position of the focused spot determined by the local tilt of the wavefront. -

Lecture 2: Geometrical Optics

Lecture 2: Geometrical Optics Outline 1 Geometrical Approximation 2 Lenses 3 Mirrors 4 Optical Systems 5 Images and Pupils 6 Aberrations Christoph U. Keller, Leiden Observatory, [email protected] Lecture 2: Geometrical Optics 1 Ideal Optics ideal optics: spherical waves from any point in object space are imaged into points in image space corresponding points are called conjugate points focal point: center of converging or diverging spherical wavefront object space and image space are reversible Christoph U. Keller, Leiden Observatory, [email protected] Lecture 2: Geometrical Optics 2 Geometrical Optics rays are normal to locally flat wave (locations of constant phase) rays are reflected and refracted according to Fresnel equations phase is neglected ) incoherent sum rays can carry polarization information optical system is finite ) diffraction geometrical optics neglects diffraction effects: λ ) 0 physical optics λ > 0 simplicity of geometrical optics mostly outweighs limitations Christoph U. Keller, Leiden Observatory, [email protected] Lecture 2: Geometrical Optics 3 Lenses Surface Shape of Perfect Lens lens material has index of refraction n o z(r) · n + z(r) f = constant n · z(r) + pr 2 + (f − z(r))2 = constant solution z(r) is hyperbola with eccentricity e = n > 1 Christoph U. Keller, Leiden Observatory, [email protected] Lecture 2: Geometrical Optics 4 Paraxial Optics Assumptions: 1 assumption 1: Snell’s law for small angles of incidence (sin φ ≈ φ) 2 assumption 2: ray hight h small so that optics curvature can be neglected (plane optics, (cos φ ≈ 1)) 3 assumption 3: tanφ ≈ φ = h=f 4 decent until about 10 degrees Christoph U. -

Utilization of a Curved Focal Surface Array in a 3.5M Wide Field of View Telescope

Utilization of a curved focal surface array in a 3.5m wide field of view telescope Lt. Col. Travis Blake Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Tactical Technology Office E. Pearce, J. A. Gregory, A. Smith, R. Lambour, R. Shah, D. Woods, W. Faccenda Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lincoln Laboratory S. Sundbeck Schafer Corporation TMD M. Bolden CENTRA Technology, Inc. ABSTRACT Wide field of view optical telescopes have a range of uses for both astronomical and space-surveillance purposes. In designing these systems, a number of factors must be taken into account and design trades accomplished to best balance the performance and cost constraints of the system. One design trade that has been discussed over the past decade is the curving of the digital focal surface array to meet the field curvature versus using optical elements to flatten the field curvature for a more traditional focal plane array. For the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) 3.5-m Space Surveillance Telescope (SST)), the choice was made to curve the array to best satisfy the stressing telescope performance parameters, along with programmatic challenges. The results of this design choice led to a system that meets all of the initial program goals and dramatically improves the nation’s space surveillance capabilities. This paper will discuss the implementation of the curved focal-surface array, the performance achieved by the array, and the cost level-of-effort difference between the curved array versus a typical flat one. 1. INTRODUCTION Curved-detector technology for applications in astronomy, remote sensing, and, more recently, medical imaging has been a component in the decision-making process for fielded systems and products in these and other various disciplines for many decades. -

A New Method for Coma-Free Alignment of Transmission Electron Microscopes and Digital Determination of Aberration Coefficients

Scanning Microscopy Vol. 11, 1997 (Pages 251-256) 0891-7035/97$5.00+.25 Scanning Microscopy International, Chicago (AMF O’Hare),Coma-free IL 60666 alignment USA A NEW METHOD FOR COMA-FREE ALIGNMENT OF TRANSMISSION ELECTRON MICROSCOPES AND DIGITAL DETERMINATION OF ABERRATION COEFFICIENTS G. Ade* and R. Lauer Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt, Bundesallee 100, D-38116 Braunschweig, Germany Abstract Introduction A simple method of finding the coma-free axis in Electron micrographs are affected by coma when the electron microscopes with high brightness guns and direction of illumination does not coincide with the direction quantifying the relevant aberration coefficients has been of the true optical axis of the electron microscope. Hence, developed which requires only a single image of a elimination of coma is of great importance in high-resolution monocrystal. Coma-free alignment can be achieved by work. With increasing resolution, the effects of three-fold means of an appropriate tilt of the electron beam incident astigmatism and other axial aberrations grow also in on the crystal. Using a small condenser aperture, the zone importance. To reduce the effect of aberrations, methods axis of the crystral is adjusted parallel to the beam and the for coma-free alignment of electron microscopes and beam is focused on the observation plane. In the slightly accurate determination of aberration coefficients are, there- defocused image of the crystal, several spots representing fore, required. the diffracted beams and the undiffracted one can be A method for coma-free alignment was originally detected. Quantitative values for the beam tilt required for proposed in an early paper by Zemlin et al. -

A Tilted Interference Filter in a Converging Beam

A&A 533, A82 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117305 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics A tilted interference filter in a converging beam M. G. Löfdahl1,2,V.M.J.Henriques1,2, and D. Kiselman1,2 1 Institute for Solar Physics, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, AlbaNova University Center, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden e-mail: [email protected] 2 Stockholm Observatory, Dept. of Astronomy, Stockholm University, AlbaNova University Center, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden Received 20 May 2011 / Accepted 26 July 2011 ABSTRACT Context. Narrow-band interference filters can be tuned toward shorter wavelengths by tilting them from the perpendicular to the optical axis. This can be used as a cheap alternative to real tunable filters, such as Fabry-Pérot interferometers and Lyot filters. At the Swedish 1-meter Solar Telescope, such a setup is used to scan through the blue wing of the Ca ii H line. Because the filter is mounted in a converging beam, the incident angle varies over the pupil, which causes a variation of the transmission over the pupil, different for each wavelength within the passband. This causes broadening of the filter transmission profile and degradation of the image quality. Aims. We want to characterize the properties of our filter, at normal incidence as well as at different tilt angles. Knowing the broadened profile is important for the interpretation of the solar images. Compensating the images for the degrading effects will improve the resolution and remove one source of image contrast degradation. In particular, we need to solve the latter problem for images that are also compensated for blurring caused by atmospheric turbulence. -

An Easy Way to Relate Optical Element Motion to System Pointing Stability

An easy way to relate optical element motion to system pointing stability J. H. Burge College of Optical Sciences University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA [email protected], (520-621-8182) ABSTRACT The optomechanical engineering for mounting lenses and mirrors in imaging systems is frequently driven by the pointing or jitter requirements for the system. A simple set of rules was developed that allow the engineer to quickly determine the coupling between motion of an optical element and a change in the system line of sight. Examples are shown for cases of lenses, mirrors, and optical subsystems. The derivation of the stationary point for rotation is also provided. Small rotation of the system about this point does not cause image motion. Keywords: Optical alignment, optomechanics, pointing stability, geometrical optics 1. INTRODUCTION Optical systems can be quite complex, using lenses, mirrors, and prisms to create and relay optical images from one space to another. The stability of the system line of sight depends on the mechanical stability of the components and the optical sensitivity of the system. In general, tilt or decenter motion in an optical element will cause the image to shift laterally. The sensitivity to motion of the optical element is usually determined using computer simulation in an optical design code. If done correctly, the computer simulation will provide accurate and complete data for the engineer, allowing the construction of an error budget and complete tolerance analysis. However, the computer-derived sensitivity may not provide the engineer with insight that could be valuable for understanding and reducing the sensitivities or for troubleshooting in the field. -

Primary Aberrations: an Investigation from the Image Restoration Perspective

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Primary Aberrations: An Investigation from the Image Restoration Perspective A Thesis Presented By Shekhar Sastry to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science In Electrical Engineering Stony Brook University May 2009 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Shekhar Sastry We, the thesis committee for the above candidate for the Master of Science degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this thesis. Dr Muralidhara Subbarao, Thesis Advisor Professor, Department of Electrical Engineering. Dr Ridha Kamoua, Second Reader Associate Professor, Department of Electrical Engineering. This thesis is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Thesis Primary Aberrations: An Investigation from the Image Restoration Perspective By Shekhar Sastry Master of Science In Electrical Engineering Stony Brook University 2009 Image restoration is a very important topic in digital image processing. A lot of research has been done to restore digital images blurred due to limitations of optical systems. Aberration of an optical system is a deviation from ideal behavior and is always present in practice. Our goal is to restore images degraded by aberration. This thesis is the first step towards restoration of images blurred due to aberration. In this thesis we have investigated the five primary aberrations, namely, Spherical, Coma, Astigmatism, Field Curvature and Distortion from a image restoration perspective. We have used the theory of aberrations from physical optics to generate the point spread function (PSF) for primary aberrations. -

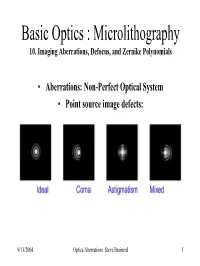

Basic Optics : Microlithography 10. Imaging Aberrations, Defocus, and Zernike Polynomials

Basic Optics : Microlithography 10. Imaging Aberrations, Defocus, and Zernike Polynomials • Aberrations: Non-Perfect Optical System • Point source image defects: 9/11/2004 Optics/Aberrations Steve Brainerd 1 Basic Optics : Microlithography 10. Imaging Aberrations, Defocus, and Zernike Polynomials • Aberrations result from a Non-Perfect Optical System • Definition of a perfect optical system: • 1. Every ray or a pencil of rays proceeding from a single object point must, after passing through the optical system converge to a single point of the image. There can be no difference between chief and marginal rays intersection in the image plane! Ray trace of simple converging lens: ray 1 = marginal ; ray 2 = chief; and ray 3 = focal 9/11/2004 Optics/Aberrations Steve Brainerd 2 Basic Optics : Microlithography 10. Imaging Aberrations, Defocus, and Zernike Polynomials • Definition of a perfect optical system: • 2. If the object is a plane surface perpendicular to the axis of the optical system, the image of any point on the object must also lie in a plane perpendicular to the axis. This means that flat objects must be imaged as flat images and curved objects as curved images. 9/11/2004 Optics/Aberrations Steve Brainerd 3 Basic Optics : Microlithography 10. Imaging Aberrations, Defocus, and Zernike Polynomials • Definition of a perfect optical system: • 3. An image must be similar to the object whether it’s linear dimensions are altered or not. This means that irregular magnification or minification cannot occur in various parts of the image relative to the object. IDEAL CASE BELOW: • Ray tracing using monochromatic light with image and object located on the optical axis and paraxial rays ( close to optic axis) typically meet this perfect image criteria. -

Sub-Aperture Piston Phase Diversity for Segmented and Multi-Aperture Systems

Sub-aperture piston phase diversity for segmented and multi-aperture systems Matthew R. Bolcar* and James R. Fienup The Institute of Optics, The University of Rochester, Rochester, New York 14627, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received 2 June 2008; accepted 7 July 2008; posted 27 August 2008 (Doc. ID 96884); published 24 September 2008 Phase diversity is a method of image-based wavefront sensing that simultaneously estimates the un- known phase aberrations of an imaging system along with an image of the object. To perform this es- timation a series of images differing by a known aberration, typically defocus, are used. In this paper we present a new method of introducing the diversity unique to segmented and multi-aperture systems in which individual segments or sub-apertures are pistoned with respect to one another. We compare this new diversity with the conventional focus diversity. © 2009 Optical Society of America OCIS codes: 100.5070, 100.3020, 110.6770, 120.0120. 1. Introduction array. Some form of actuation is necessary to main- Modern ground-based and space-based observatories tain equivalent optical path distances (OPDs) be- are nearing the limits on the size and weight of tween the segments or sub-apertures. In the case monolithic primary mirrors, hindering an increase of segmented systems such as the JWST, actuation in both light collecting efficiency and imaging resolu- is achieved by mounting each hexagonal segment tion. In response, technology is heading in the direc- on a hexapod, allowing for seven degrees of freedom: tion of segmented and multi-aperture systems as the x and y translation, clocking, piston, tip, tilt, next generation of telescopes. -

Basic Wavefront Aberration Theory for Optical Metrology

APPLIED OPTICS AND OPTICAL ENGINEERING, VOL. Xl CHAPTER 1 Basic Wavefront Aberration Theory for Optical Metrology JAMES C. WYANT Optical Sciences Center, University of Arizona and WYKO Corporation, Tucson, Arizona KATHERINE CREATH Optical Sciences Center University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona I. Sign Conventions 2 II. Aberration-Free Image 4 III. Spherical Wavefront, Defocus, and Lateral Shift 9 IV. Angular, Transverse, and Longitudinal Aberration 12 V. Seidel Aberrations 15 A. Spherical Aberration 18 B. Coma 22 C. Astigmatism 24 D. Field Curvature 26 E. Distortion 28 VI. Zernike Polynomials 28 VII. Relationship between Zernike Polynomials and Third-Order Aberrations 35 VIII. Peak-to-Valley and RMS Wavefront Aberration 36 IX. Strehl Ratio 38 X. Chromatic Aberrations 40 XI. Aberrations Introduced by Plane Parallel Plates 40 XII. Aberrations of Simple Thin Lenses 46 XIII.Conics 48 A. Basic Properties 48 B. Spherical Aberration 50 C. Coma 51 D. Astigmatism 52 XIV. General Aspheres 52 References 53 1 Copyright © 1992 by Academic Press, Inc. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. ISBN 0-12-408611-X 2 JAMES C. WYANT AND KATHERINE CREATH FIG. 1. Coordinate system. The principal purpose of optical metrology is to determine the aberra- tions present in an optical component or an optical system. To study optical metrology, the forms of aberrations that might be present need to be understood. The purpose of this chapter is to give a brief introduction to aberrations in an optical system. The goal is to provide enough information to help the reader interpret test results and set up optical tests so that the accessory optical components in the test system will introduce a minimum amount of aberration. -

Subjective Refraction and Prescribing Glasses

Subjective Refraction and Prescribing Glasses The Number One (or Number Two) Guide to Practical Techniques and Principles Richard J. Kolker, MD Subjective Refraction and Prescribing Glasses: Guide to Practical Techniques and Principles November 2014 The author states that he has no financial or other relationship with the manufacturer of any commercial product or provider of any commercial service discussed in the material he contributed to this publication or with the manufacturer or provider of any competing product or service. Initial Reviews "Wow, a fantastic resource! Giants like you and David Guyton who can make refraction understandable and enjoyable are key. This book will make it so much easier for our residents." —Tara A. Uhler, MD Director, Resident Education Wills Eye Hospital "Subjective Refraction and Prescribing Glasses: Guide to Practical Techniques and Principles is really awesome." —Jean R. Hausheer, MD, FACS Clinical Professor Dean McGee Eye Institute Many thanks for volunteering your time and expertise for the benefit of resident education. —Richard Zorab Vice President of Clinical Education American Academy of Ophthalmology Copyright © 2015 Richard J. Kolker, MD All rights reserved. 2 Subjective Refraction and Prescribing Glasses: Guide to Practical Techniques and Principles Contents About the Author, Acknowledgments 4 Foreword by David L. Guyton, MD 5 Preface 6 Introduction 7 1. Practical Optics • Goal of Refraction, Six Principles of Refraction, Snellen Visual Acuity 8 • Spherical Refractive Errors 9 • Astigmatism