Mali Transition Initiative Final Evaluation Scope of Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Région De Mopti

Région de Mopti Faits saillants dans la région avec impact sur l’accès humanitaire Cercles de la région Gao Le 05 septembre 2020, le GIAC a recommandé cinq (5) jours de suspension des mouvements des humanitaires sur la route Tombouctou nationale 15 (RN15) pour faire une analyse des interventions humanitaires dans un contexte sécuritaire marqué par l’attaque de deux véhicules d’une mission humanitaire sur la RN15 le 04 Youwarou Douentza septembre 2020. Mopti Tenenkou Bandiagara Des attaques récurrentes et indiscriminées de personnes armées Mopti non identifiées contre des véhicules et une position de milices Koro locales, de chasseurs enregistrés sur la RN15 près du village Tillé, Djenne Burkina Bankass commune de Doucoumbo, entre le 28 novembre et le 10 décembre Ségou Faso 2020 ont entrainé un ralentissement des missions humanitaires sur la RN15, les instigateurs de ces attaques n’étant pas formellement identifié, acteurs humanitaires redoutaient de se retrouver touché intercommunautaires. L’insécurité qui sévissait dans plusieurs par ces attaques indiscriminées communes dont Diankabou, de Madougou, de Dioungani depuis Le blocage des patrouilles de la MINUSMA par les milices locales deux ans a été considérablement réduite grâce à ces accords et avec parfois la participation de la population civile à Bandiagara à aux dialogues qui les ont précédés. Les activités pastorales et partir du 18 décembre 2020 avec pour impacte l’arrêt des patrouilles agricoles dans plusieurs localités ont repris ainsi que les marchés et le retrait de la base temporaire et opérationnelle (TOB) de la hebdomadaires force de la MINUSMA dans le cadre de la sécurisation de la RN15 Dans le cercle de Douentza, 82 chefs de village des communes de a été signalé. -

R E GION S C E R C L E COMMUNES No. Total De La Population En 2015

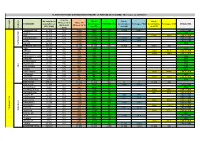

PLANIFICATION DES DISTRIBUTIONS PENDANT LA PERIODE DE SOUDURE - Mise à jour au 26/05/2015 - % du CH No. total de la Nb de Nb de Nb de Phases 3 à 5 Cibles CH COMMUNES population en bénéficiaires TONNAGE CSA bénéficiaires Tonnages PAM bénéficiaires Tonnages CICR MODALITES (Avril-Aout (Phases 3 à 5) 2015 (SAP) du CSA du PAM du CICR CERCLE REGIONS 2015) TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 12% 8 044 8 044 217 10 055 699,8 CSA + PAM ALAFIA 15 844 12% 1 901 1 901 51 CSA BER 23 273 12% 2 793 2 793 76 6 982 387,5 CSA + CICR BOUREM-INALY 14 239 12% 1 709 1 709 46 2 438 169,7 CSA + PAM LAFIA 9 514 12% 1 142 1 142 31 1 427 99,3 CSA + PAM SALAM 26 335 12% 3 160 3 160 85 CSA TOMBOUCTOU TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 18 748 18 749 506 13 920 969 6 982 388 DIRE 24 954 10% 2 495 2 495 67 CSA ARHAM 3 459 10% 346 346 9 1 660 92,1 CSA + CICR BINGA 6 276 10% 628 628 17 2 699 149,8 CSA + CICR BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 10% 1 050 1 050 28 CSA DANGHA 15 835 10% 1 584 1 584 43 CSA GARBAKOIRA 6 934 10% 693 693 19 CSA HAIBONGO 17 494 10% 1 749 1 749 47 CSA DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 10% 506 506 14 CSA KONDI 3 744 10% 374 374 10 CSA SAREYAMOU 20 794 10% 2 079 2 079 56 9 149 507,8 CSA + CICR TIENKOUR 8 009 10% 801 801 22 CSA TINDIRMA 7 948 10% 795 795 21 2 782 154,4 CSA + CICR TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 10% 356 356 10 CSA DIRE TOTAL 134 559 13 456 13 456 363 0 0 16 290 904 GOUNDAM 15 444 15% 2 317 9 002 243 3 907 271,9 CSA + PAM ALZOUNOUB 5 493 15% 824 3 202 87 CSA BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 15% 1 530 5 946 161 4 080 226,4 CSA + CICR ADARMALANE 1 172 15% 176 683 18 469 26,0 CSA + CICR DOUEKIRE 22 203 15% 3 330 -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Agriculture and Food Security

QUARTERLY REPORT Project Name: Socioeconomic Reintegration of Vulnerable Rural Malian Households Country: Mali Agreement Number: AID-OFDA-G-14-00066 Reporting Period: April- June 2015 OVERVIEW After 15 months of implementation including a 4 months No Cost Extension period, the project has just ended on June, 30th 2015. During this quarter, the activities went smoothly despite the critical insecurity events that occurred in Timbuktu region which caused the temporarily staff relocation. It concerned mainly: Recruitment of an external consultant for the project's ongoing final evaluation; Cash transfer to 233 newly returnee women to finance their Income Generating Activities (IGAs); Training of Trainers and Livestock’s beneficiaries in animal health and good practices in breeding small ruminants; Drafting of the IGAs and livestock intermediary reports; Monitoring activities (rice off-crop season, market gardening, livestock and IGAs ); Delivery of 50 motor pumps to 50 gardening perimeters retained to support women in their gardening activities; An audiovisual documentation on the best practices and project successes. In June, a report on the achievements and success of the project was done to produce an audiovisual materials for the civil society, humanitarian actors, authorities and the general public to learn about the different activities and the successes achieved by the beneficiaries. This report aims to: Valorize the project implementation approach and methodology; Present beneficiaries' testimonials (especially women) about the support received, its uses, and their satisfaction; Present the impacts and changes that occurred through the project achieved activities in the areas of food security & agriculture (gardening, rice, livestock) and the economic revival (Income Generating Activities); Gather opinions on the project's impact on promoting women’s status and social cohesion in families and communities. -

Pnr 2015 Plan Distribution De

Tableau de Compilation des interventions Semences Vivrières mise à jour du 03 juin 2015 Total semences (t) Total semences (t) No. total de la Total ménages Total Semences (t) Total ménages Total semences (t) COMMUNES population en Save The Save The CERCLE CICR CICR FAO REGIONS 2015 (SAP) FAO Children Children TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 ALAFIA 15 844 BER 23 273 1 164 23,28 BOUREM-INALY 14 239 1 168 23,36 LAFIA 9 514 854 17,08 TOMBOUCTOU SALAM 26 335 TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 DIRE 24 954 688 20,3 ARHAM 3 459 277 5,54 BINGA 6 276 450 9 BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 DANGHA 15 835 437 13 GARBAKOIRA 6 934 HAIBONGO 17 494 482 3,1 DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 KONDI 3 744 SAREYAMOU 20 794 1 510 30,2 574 3,3 TIENKOUR 8 009 TINDIRMA 7 948 397 7,94 TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 DIRE TOTAL 134 559 GOUNDAM 15 444 ALZOUNOUB 5 493 BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 680 6,8 ADARMALANE 1 172 78 0,78 DOUEKIRE 22 203 DOUKOURIA 3 393 ESSAKANE 13 937 929 9,29 GARGANDO 10 457 ISSA BERY 5 063 338 3,38 TOMBOUCTOU KANEYE 2 861 GOUNDAM M'BOUNA 4 701 313 3,13 RAZ-EL-MA 5 397 TELE 7 271 TILEMSI 9 070 TIN AICHA 3 653 244 2,44 TONKA 65 372 190 4,2 GOUNDAM TOTAL 185 687 RHAROUS 32 255 1496 18,7 GOURMA-RHAROUS TOMBOUCTOU BAMBARA MAOUDE 20 228 1 011 10,11 933 4,6 BANIKANE 11 594 GOSSI 29 529 1 476 14,76 HANZAKOMA 11 146 517 6,5 HARIBOMO 9 045 603 7,84 419 12,2 INADIATAFANE 4 365 OUINERDEN 7 486 GOURMA-RHAROUS SERERE 10 594 491 9,6 TOTAL G. -

PROGRAMME ATPC Cartographie Des Interventions

PROGRAMME ATPC Cartographie des interventions Agouni !( Banikane !( TOMBOUCTOU Rharous ! Ber . !( Essakane Tin AÎcha !( Tombouctou !( Minkiri Madiakoye H! !( !( Tou!(cabangou !( Bintagoungou M'bouna Bourem-inaly !( !( Adarmalane Toya !( !( Aglal Raz-el-ma !( !( Hangabera !( Douekire GOUNDAM !( Garbakoira !( Gargando Dangha !( !( G!(ou!(ndam Sonima Doukouria Kaneye Tinguereguif Gari !( .! !( !( !( !( Kirchamba TOMBOUCTOU !( MAURITANIE Dire .! !( HaÏbongo DIRE !( Tonka Tindirma !( !( Sareyamou !( Daka Fifo Salakoira !( GOURMA-RHAROUS Kel Malha Banikane !( !( !( NIAFOUNKE Niafunke .! Soumpi Bambara Maoude !( !( Sarafere !( KoumaÏra !( Dianke I Lere !( Gogui !( !( Kormou-maraka !( N'gorkou !( N'gouma Inadiatafane Sah !( !( !( Ambiri !( Gathi-loumo !( Kirane !( Korientze Bafarara Youwarou !( Teichibe !( # YOUWAROU !( Kremis Guidi-sare !( Balle Koronga .! !( Diarra !( !( Diona !( !( Nioro Tougoune Rang Gueneibe Nampala !( Yerere Troungoumbe !( !( Ourosendegue !( !( !( !( Nioro Allahina !( Kikara .! Baniere !( Diaye Coura !( # !( Nara Dogo Diabigue !( Gavinane Guedebin!(e Korera Kore .! Bore Yelimane !( Kadiaba KadielGuetema!( !( !( !( Go!(ry Youri !( !( Fassoudebe Debere DOUENTZA !( .! !( !( !(Dallah Diongaga YELIMANE Boulal Boni !( !(Tambacara !( !( Takaba Bema # # NIORO !( # Kerena Dogofiry !( Dialloube !( !( Fanga # Dilly !( !( Kersignane !( Goumbou # KoubewelDouentza !( !( Aourou !( ## !( .! !( # K#onna Borko # # #!( !( Simbi Toguere-coumbe !( NARA !( Dogani Bere Koussane # !( !( # Dianwely-maounde # NIONO # Tongo To !( Groumera Dioura -

Rapport CMP JANVIER 2020 Date De Production

JANVIER 2020 RAPPORT SUR LES MOUVEMENTS DE POPULATIONS RAPPORT SUR LES MOUVEMENTS DE POPULATIONS La crise humanitaire qui affecte le Mali depuis 2012 a généré des déplacements massifs de populations, tant à l’intérieur qu’à l’extérieur du pays, avec d’importantes répercussions sur les pays voisins, notamment le Burkina Faso, le Niger et la Mauritanie. Depuis 2018, un nouveau cycle de violence a aggravé la situation et provoque des déplacements forcés. Chaque jour, de nouvelles personnes déplacées internes (PDI) continuent d’être enregistrés. Ces mouvements ont un impact considérable sur les personnes forcées de fuir leurs foyers et sur les communautés qui les accueillent. Afin de répondre aux besoins des populations déplacées internes, rapatriées et retournées, la Commission Mouvement de Populations (CMP) recueille et analyse les informations sur les mouvements de populations à l’intérieur du Mali, afin de fournir un état complet des mouvements de populations et à la demande de ses partenaires. Les membres de la Commission sont : la Direction Générale de la Protection Civile (Ministère de la sécurité intérieur), UNHCR, OCHA, PAM, UNICEF, ACTED, NRC, DRC, HI, Solidarités International, CRS, OIM, et DNDS. Plusieurs autres entités participent régulièrement aux rencontres de la Commission. Résumé : A la date du 31 janvier 2020, les partenaires de la CMP ont comptabilisé : 140 8001 réfugiés maliens dans les pays limitrophes par l’UNHCR. La population déplacée est composée de La population déplacée est composée de 54% de femmes. 46% d’hommes. 53% de la population déplacée interne est Les personnes de plus de 60 ans composée d’enfants de moins de 18 ans. -

Rapport Sur Les Mouvements De Populations Rapport Sur Les Mouvements De Populations

Février 2020 RAPPORT SUR LES MOUVEMENTS DE POPULATIONS RAPPORT SUR LES MOUVEMENTS DE POPULATIONS La crise humanitaire qui affecte le Mali depuis 2012 a généré des déplacements massifs de populations, tant à l’intérieur qu’à l’extérieur du pays, avec d’importantes répercussions sur les pays voisins, notamment le Burkina Faso, le Niger et la Mauritanie. Depuis 2018, un nouveau cycle de violence a aggravé la situation et provoque des déplacements forcés. Chaque jour, de nouvelles personnes déplacées internes (PDI) continuent d’être enregistrés. Ces mouvements ont un impact considérable sur les personnes forcées de fuir leurs foyers et sur les communautés qui les accueillent. Afin de répondre aux besoins des populations déplacées internes, rapatriées et retournées, la Commission Mouvement de Populations (CMP) recueille et analyse les informations sur les mouvements de populations à l’intérieur du Mali, afin de fournir un état complet des mouvements de populations et à la demande de ses partenaires. Les membres de la Commission sont : la Direction Générale de la Protection Civile (Ministère de la sécurité intérieur), UNHCR, OCHA, PAM, UNICEF, ACTED, NRC, DRC, HI, Solidarités International, CRS, OIM, et DNDS. Plusieurs autres entités participent régulièrement aux rencontres de la Commission. Résumé : A la date du 29 février 2020, les partenaires de la CMP ont comptabilisé : 140 8001 réfugiés maliens dans les pays limitrophes par l’UNHCR. La population déplacée est composée de La population déplacée est composée de 54% de femmes. 46% d’hommes. 53% de la population déplacée interne est Les personnes de plus de 60 ans composée d’enfants de moins de 18 ans. -

Monthly Bulletin

Highlights #20 | September 2016 Trust Fund: inauguration of newly Monthly Bulletin rehabilitated Sévaré FAMa Camp with the Ambassador of Canada Kidal: rehabilitation of 2 schools and creation Role of the S&R Section of a fodder purchase centre (Trust Fund) Mopti: new borehole in Kanio (QIP) In support to the Deputy Special Representative Through this monthly bulletin, we provide regular Peacebuilding Fund: documentary on 1st phase of the Secretary-General (DSRSG), Resident updates on stabilization & recovery developments achievements Coordinator (RC) and Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) and activities in the north of Mali. The intended Heritage rehabilitation: official visit in Timbuktu in her responsibilities to lead the United Nations’ audience is the section’s main partners including More projects launched in northern regions contribution to Mali’s reconstruction efforts, the MINUSMA military and civilian components, UNCT Stabilization & Recovery section (S&R) promotes and international partners. Main Figures synergies between MINUSMA, the UN Country Team and other international partners. For more information: QIPs 2015-2016: 96 projects out of which 32 Gabriel Gelin, Information Specialist (S&R completed and 64 under implementation over a total section) - [email protected] budget of 4 million USD (205 projects since 2013 over a budget of 7.8 million USD) Peacebuilding Fund (PBF): 5 projects started Donor Coordination and Partnerships in 2015 over 18 months for a total budget of 10,932,168 USD On 8th of September, the Commission Trust Fund -

Rapport Sur Les Mouvements De Populations Rapport Sur Les Mouvements De Populations

19 Décembre 2019 RAPPORT SUR LES MOUVEMENTS DE POPULATIONS RAPPORT SUR LES MOUVEMENTS DE POPULATIONS La crise humanitaire qui affecte le Mali depuis 2012 a généré des déplacements massifs de populations, tant à l’intérieur qu’à l’extérieur du pays, avec d’importantes répercussions sur les pays voisins, notamment le Burkina Faso, le Niger et la Mauritanie. Depuis 2018, un nouveau cycle de violence a aggravé la situation et provoque des déplacements forcés. Chaque jour, de nouvelles personnes déplacées internes (PDI) continuent d’être enregistrés. Ces mouvements ont un impact considérable sur les personnes forcées de fuir leurs foyers et sur les communautés qui les accueillent. Afin de répondre aux besoins des populations déplacées internes, rapatriées et retournées, la Commission Mouvement de Populations (CMP) recueille et analyse les informations sur les mouvements de populations à l’intérieur du Mali, afin de fournir un état complet des mouvements de populations et à la demande de ses partenaires. Les membres de la Commission sont : la Direction Générale de la Protection Civile (Ministère de la sécurité intérieur), UNHCR, OCHA, PAM, UNICEF, ACTED, NRC, DRC, HI, Solidarités International, CRS, OIM, et DNDS. Plusieurs autres entités participent régulièrement aux rencontres de la Commission. Résumé : A la date du 30 novembre 2019, les partenaires de la CMP ont comptabilisé : 138 6591 réfugiés maliens dans les pays limitrophes par l’UNHCR. La population déplacée est composée de La population déplacée est composée de 54% de femmes. 46% d’hommes. 53% de la population déplacée interne est Les personnes de plus de 60 ans composée d’enfants de moins de 18 ans. -

Kidal : Inauguration of the Renovated Coordinator (RC) and Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) and Activities in the North of Mali

Highlights #11 | December 2015 CREED: new Strategic Framework for Economic Monthly Bulletin Recovery and Sustainable Development of Mali Peacebuilding Fund: new activities on UNICEF and UNOPS projects Role of the S&R Section Trust Fund in support for Peace and Security in Mali: Denmark contribution In support to the Deputy Special Representative Through this monthly bulletin, we provide regular Mopti: support to Sévaré Prison and MDSF of the Secretary-General (DSRSG), Resident updates on stabilization & recovery developments Kidal : inauguration of the renovated Coordinator (RC) and Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) and activities in the north of Mali. The intended Municipal Stadium in her responsibilities to lead the United Nations’ audience is the section’s main partners including Tessalit: support to the Centre de Santé and contribution to Mali’s reconstruction efforts, the MINUSMA military and civilian components, UNCT water well in Amachache Stabilization & Recovery section (S&R) promotes and international partners. Gao: solar public lightning in town synergies between MINUSMA, the UN Country Team More QIPs launched in northern regions and other international partners. For more information: Gabriel Gelin, Information Specialist (S&R section) - [email protected] Main Figures QIPs: 138 projects with 74 completed and 64 Donor Coordination and Partnerships under implementation Peacebuilding Fund (PBF): 5 projects started th th On 17 and 18 of December 2015, Relance Economique et le Développement Durable in 2015 for a total budget of 10,932,168 -

A 82 Electionscommunales 20

MINISTERE DE L’ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI DE LA DECENTRALISATION UN PEUPLE-UN BUT-UNE FOI ET DE LA REFORME DE L’ETAT ************** ************** SYNTHESE DES RESULTATS COMPLETS DES ELECTIONS COMMUNALES DU 20 NOVEMBRE 2016 FEVRIER 2017 MINISTERE DE L’ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DE LA REFORME DE L’ETAT BP : 215 Bamako-Mali ; Tél. : 20 22 42 12 ; Fax : 20 23 02 47 ; Site web : www.matcl.gov.ml Introduction Le 20 novembre 2016, ont eu lieu au Mali les quatrièmes élections communales de l’ère démocratique faisant suite à celles de 1999, 2004 et 2009. Les élections sont un moment privilégié pour évaluer l’implantation du processus électoral dans le paysage institutionnel malien, notamment après la crise politico sécuritaire que le pays a traversée. L’analyse des résultats de ces élections permet ainsi d’apprécier, à travers divers indicateurs, l’importance de la décentralisation et des communes dans la vie des citoyens. Le présent document présente une synthèse des principaux résultats (candidatures, participation, résultats par liste et analyse des données sur les élus) des élections communales du 20 novembre 2016. Les données sont présentées globalement au niveau national (certains graphiques montrent le détail par région) Une comparaison avec les résultats des élections communales de 2004 et 2009 est systématiquement réalisée, ainsi que dans certains cas avec celles de 1999, afin de montrer les évolutions. Tenue des élections Les élections communales se sont déroulées pour la première fois au Mali sous l’état d’urgence. Elles n’ont pas pu se tenir dans 59 communes au total : - Dans 15 communes aucune candidature n’a été enregistrée.