Playing by Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notre Dame Collegiate Jazz Festival Program, 2005

Archives of the University of Notre Dame Archives of the University of Notre Dame ro WEDNESDAY, FEB. 23, 2005 Preview Night. LaFortune Ballroom. FREE .-> 8:00 p.m. University of Notre Dame Jazz Band II and Jazz Combo -I-J (J) FRIDAY, FEB. 25, 2005 Evening concert block. Washington Hall. FREE for Students; Non-students $3 for 1 night, $5 for both nights OJ U 6:00 p.m. Oberlin College Small Jazz Ensemble N N 6:45 p.m. Western Michigan UniversityCombo ro 7:30 p.m. University of Illinois Concert Jazz Band --, 8: 15 p.m. Oberlin College Jazz Ensemble 9:00 p.m. Western Michigan UniversityJazz Orchestra OJ 9:45 p.m. Judges' Jam ro-I-J :Jro Frank Catalano (saxophone) c· Andre Hayward (trombone) cO) Lynne Arriale (piano) <{OJ Jay Anderson (bass) ...c:= Steve Davis (drums) ~O ~U SATURDAY, FEB. 26, 2005 Clinic. Notre Dame Band Building. FREE 2-3:00 p.m. Meet in main rehearsal room. Evening concert block. Washington Hall. Free for Students; Non-students $3 for 1 night, $5 for both nights 6:00 p. m. University of Notre Dame Jazz Band I 6:45 p.m. Middle Tennessee State UniversityJazz Ensemble I 7:30 p.m. Jacksonville State UniversityJazz Ensemble I 8: 15 p.m. Carnegie Mellon University 6:30 Jazz Ensemble 9:00 p.m. University of Notre Dame Brass Band 9:45 p.m. Collegiate Jazz Festival Alumni Combo Archives of the University of Notre Dame Festival Director: Greg Salzler OJ Assistant to the Director: WillSeath OJ ~ Festival Graphic Designer: Melissa Martin ~ Student Union Board Advisor: Erin Byrne , Faculty advisorto the festival: Larry Dwyer E SUB E-Board: Jimmy Flaherty E Patrick Vassel e Lauren Hallemann u - HeatherKimmins ro John McCarthy > Caitlin Burns .- ~ MarkHealy (J) OJ (J) 1 Jazz Festival Committee Special Thanks to: Ourguests L.L. -

Jazz Guitar Talk 10 Great Jazz Guitarists Discuss Jazz Guitar Education © Playjazzguitar.Com

Play Jazz Guitar .com presents Jazz Guitar Talk 10 Great jazz guitarists discuss jazz guitar education © PlayJazzGuitar.com You are welcome to pass this eBook along to your friends. You are also welcome to offer it as a free download on your website provided that you do not alter the text in any way and the document is kept 100% intact. Index Steve Khan 3 Sid Jacobs 8 Jack Wilkins 10 Mike Clinco 13 Richard Smith 15 Jeff Richman 17 Mark Stefani 19 Larry Koonse 22 Henry Johnson 24 Pat Kelley 27 From Chris Standring www.ChrisStandring.com www.PlayJazzGuitar.com Hi there and welcome to Jazz Guitar Talk - boy it sounds like a radio show doesn't it? Well thanks for downloading this eBook, I sure hope it helps put some of your educational queries in perspective. What we have here is a small select group of musical perfectionists, all of whom have dedicated their lives to mastering the art of jazz guitar at the highest level. Jazz guitar instruction it seems is very personal and all who teach it usually teach their own methods and systems with fervor. It's also quite interesting to me how one great player can have a whole different slant on teaching jazz than another. Because instruction seems so personal I wanted to invite some of the world's finest players and educators to answer exactly the same questions. This way we could find out what really was common to all and what was not. The answers were fascinating and it only confirmed how unique everybody is in the jazz guitar world. -

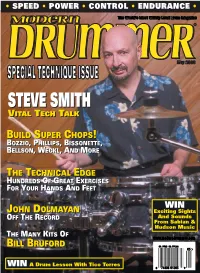

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

JAZZIZ-Metheny-Interviews.Pdf

Pat Metheny www.jazziz.com JAZZIZ Subscription Ad Lage.pdf 1 3/21/18 10:32 AM Pat Metheny Covered Though I was a Pat Metheny fan for nearly a decade before I special edition, so go ahead and make fun if you please). launched JAZZIZ in 1983, it was his concert, at an outdoor band In 1985, we published a cover story that included Metheny, shell on the University of Florida campus, less than a year but the feature was about the growing use of guitar synthesizers before, that got me to focus on the magazine’s mission. in jazz, and we ran a photo of John McLaughlin on the cover. As a music reviewer for several publications in the late Strike two. The first JAZZIZ cover that featured Pat ran a few ’70s and early ’80s, I was in touch with ECM, the label for years later, when he recorded Song X with Ornette Coleman. whom Metheny recorded. It was ECM that sent me the press When the time came to design the cover, only photos of Metheny credentials that allowed me to go backstage to interview alone worked, and Pat was unhappy with that because he felt Metheny after the show. By then, Metheny had recorded Ornette should have shared the spotlight. Strike three. C around 10 LPs with various instrumental lineups: solo guitar, A few years later, I commissioned Rolling Stone M duo work with Lyles Mays on the chart-topping As Wichita Fall, photographer Deborah Feingold to do a Metheny shoot for a Y So Falls Wichita Falls, trio, larger ensembles and of course his Pat cover story that would delve into his latest album at the time. -

Roger Sadowsky Carves a Guitar Neck by Hand

Right: Roger Sadowsky carves a guitar neck by hand. Below: Roger takes a break beneath a wall of customized guitars and basses. ROGER SADOWSKY he job of the instrument maker is to provide a tool that “ allows the musician to express himself. Ultimately, the changes in sound and design don’t come from us, but New York’s T from innovative musicians whose talent demands something new. The most dramatic example we get is people Acclaimed Craftsman from all over the world requesting the ‘Marcus Miller bass sound’.” Tailors Instruments —Roger Sadowsky For Everyone From “Roger was the first repairman to take an interest in my playing. He asked a lot of questions concerning how hard I played, the Springsteen and Sting kinds of music I was involved with, and what sort of sound I was looking for. He has great insight into the wood and To Di Meola And Stern electronics that make up an instrument, and he suggested I try one of his preamps. At the time, I was having trouble conveying my style through my bass. With the preamp, I gradually noticed that I could do more with the instrument and the sound was By Chris Jisi projecting better. What Roger did was give me a sound with which I could communicate my style.” —Marcus Miller PHOTOS BY EBET ROBERTS PHOTOS Similar accolades arrive from all corners of the music busi- New York in 1979, 95% of my clients were top studio and ness for New York luthier/repairman Roger Sadowsky, from guitar touring musicians in town. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

October 1994

Features AARON COMESS Album number two sees Spin Doctors drummer Aaron Comess laying down that slippery funky thing yet again. Not that Aaron has cut down on his extracurricular jazz work. Does this guy ever stop? • Teri Saccone 20 BOB MOSES The eccentric but unarguably gifted drummer who powered the first jazz-rock band is still breaking barriers. With a brand- new album and ever-probing style, Bob Moses explains why his "Simul-Circular Loopology" might be too dangerous in live doses. • Ken Micallef 26 HIGHLIGHTS OF MD's FESTIVAL WEEKEND '94 Where should we start? Simon Phillips? Perhaps "J.R." Robinson? Say, Rod Morgenstein? How about Marvin "Smitty" Smith...or David Garibaldi...maybe Chad Smith, Clayton Cameron, or Matt Sorum.... Two days, one stage, a couple thousand drummers, mega-prizes: No matter how you slice it, it's the mother of all drum shows, and we've got the photos to prove it! 30 Volume 18, Number 9 Cover Photo By Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 52 DRUM SOLOIST 8 UPDATE Max Roach: Bill Bruford, "Blues For Big Sid" David Garibaldi, TRANSCRIBED BY Dave Mancini, CRAIG SCOTT and Ray Farrugia of Junkhouse, plus News 76 HEALTH & SCIENCE 119 INDUSTRY Focal Dystonia: HAPPENINGS A Personal Experience BY CHARLIE PERRY WITH JACK MAKER DEPARTMENTS 42 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP 80 JAZZ 4 EDITOR'S Tama Iron Cobra DRUMMERS' OVERVIEW Bass Drum Pedals WORKSHOP BY ADAM BUDOFSKY Expanding The 6 READERS' 43 Tama Tension Watch Learning Process PLATFORM Drum Tuner BY JOHN RILEY BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 12 ASK A PRO 84 Rock 'N' 44 Vic Firth Ed Shaughnessy, American Concept Sticks JAZZ CLINIC Stephen Perkins, and BY WILLIAM F. -

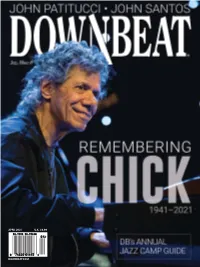

Downbeat.Com April 2021 U.K. £6.99

APRIL 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM April 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

John Surman Brewster’S Rooster

ECM John Surman Brewster’s Rooster John Surman: baritone and soprano saxophones; John Abercrombie: guitar; Drew Gress: double-bass; Jack DeJohnette: drums ECM 2046 06025 270 1112 (7) Release: June 2009 After many adventures through the genres, a jazz album. The wide range of John Surman’s musical interests has, in the last several years seen him in contexts ranging from early music with John Potter’s Dowland Project to Arab modes with Anouar Brahem, while his own albums have included encounters with church organ (“Rain on the Window”), strings (“The Spaces in Between”), classical brass ensemble (“Free and Equal”), and choir (“Proverbs and Songs”). “Brewster’s Rooster”, however, is in another tradition. For long-time Surman listeners it will likely bring to mind earlier meetings with his extraordinarily mobile baritone and fleet soprano – on his own “Stranger Than Fiction” or “Adventure Playground” albums, perhaps, or on Mick Goodrick’s “In Pas(s)ing” (a disc that also featured Jack DeJohnette’s drums), or with The Trio on Barre Phillips’s Mountainscapes” (which also included a guest role for John Abercrombie). “Brewster’s Rooster” draws upon much shared musical experience. Abercrombie and DeJohnette have also played together often since the early 70s, the former a member of several of the latter’s bands. Guitarist and drummer also played on sessions for ECM artists from Collin Walcott to Kenny Wheeler, and comprised two-thirds of the powerful Gateway trio. John Surman and Jack DeJohnette, meanwhile, have collaborated intermittently for more than 40 years, first meeting at a jam session at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in 1968 when Jack was in London with Bill Evans. -

September 1994

Contents Features DENNIS CHAMBERS Baltimore's most monstrous drummin' son just keeps on going. John McLaughlin, Steve Khan, the Brecker Brothers— jazz giants left and right are squeezing Dennis into their plans these days. Get the latest from the drummer many consider the greatest. • Robin Tolleson 20 JIM CHAPIN Asking your average drummer about Jim Chapin's Advanced Techniques For The Modern Drummer is like asking your aver- age Jesuit priest about The Bible. This month MD taps the mind of one of drum-dom's acknowledged sages. • Rick Mattingly 26 SIM CAIN Henry Rollins is a seriously fierce performer. His band obvious- ly has to kick equally serious butt. Drummer Sim Cain describes the controlled chaos he negotiates every day—and the surprisingly varied back- ground that feeds his style. • Matt Peiken 30 DRUM THRONES UP CLOSE Everyone knows the drummer is king, so it's no accident our stool is called "the drum throne." But the drummer's job also depends on comfort—and our seat needs to serve that "end" as well as possible. In this spe- cial report, MD covers today's stool scene from AtoZ. • Rick Van Horn 34 Volume 18, Number 9 Cover photo of Dennis Chambers by Michael Bloom Jim Chapin by Rick Malkin Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 48 LATIN 8 UPDATE SYMPOSIUM Phillip Rhodes of Applying The Clave Gin Blossoms, BY CHUCK SILVERMAN Brother Cane's Scott Collier, Akira Jimbo, and Jeff Donavan of 56 Rock'N' the Paladins, plus News JAZZ CLINIC Doubling Up: Part 2 120 INDUSTRY BY ROD MORGENSTEIN HAPPENINGS 74 JAZZ DRUMMERS' DEPARTMENTS WORKSHOP -

Monterey Jazz Festival Next Generation Orchestra

March / April 2017 Issue 371 now in our 43rd year jazz &blues report MONTEREY JAZZ FESTIVAL NEXT GENERATION ORCHESTRA March • April 2017 • Issue 371 MONTEREY JAZZ FESTIVAL jazz NEXT GENERATION ORCHESTRA &blues report Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Layout & Design Bill Wahl Operations Jim Martin Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. RIP JBR Writers Tom Alabiso, John Hunt, Chris Colombi, Mark A. Cole, Hal Hill Check out our constantly updated website. All of our issues from our first PDFs in September 2003 and on are posted, as well as many special issues with festival reviews, Blues Cruise and Gift Guides. Now you can search for CD Re- views by artists, titles, record labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 years of reviews are up from our archives and we will be adding more, especially from our early years back to 1974. 47th Annual Next Generation Jazz Festival Presented by Monterey Jazz Festival Hosts Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com Web www.jazz-blues.com America’s Top Student Jazz Musicians, Copyright © 2017 Jazz & Blues Report March 31-April 2 in Monterey CA No portion of this publication may be re- Monterey, Calif., March 1, 2017; The 47th Annual Next Generation Jazz produced without written permission from Festival Presented by Monterey Jazz Festival takes place March 31- April 2, the publisher. All rights Reserved. 2017 in downtown Monterey. The weekend-long event includes big bands, Founded in Buffalo New York in March of combos, vocal ensembles, and individual musicians vying for a spot on the 1974; began our Cleveland edition in April of 1978. -

Gary Burton & M. Ozone

This pdf was last updated: Apr/23/2010. Gary Burton & M. Ozone Gary Burton and Makoto Ozone are so telepathically in sync as a duo and with they have such an innate feel for the space between jazz and classical music. Line-up Gary Burton - vibraphone Makoto Ozone - piano On Stage: 2 Travel Party: 3 Website www.garyburton.com Biography Gary Burton: One of the two great vibraphonists to emerge in the 1960s (along with Bobby Hutcherson), Gary Burton's remarkable four-mallet technique can make him sound like two or three players at once. He recorded in a wide variety of settings and always sounds distinctive. Self-taught on vibes, Burton made his recording debut with country guitarist Hank Garland when he was 17, started recording regularly for RCA in 1961, and toured with George Shearing's quintet in 1963. He gained some fame while with Stan Getz's piano-less quartet during 1964-1966, and then put together his own groups. In 1967, with guitarist Larry Coryell, he led one of the early "fusion" bands; Coryell would later be succeeded by Sam Brown, Mick Goodrick, John Scofield, Jerry Hahn, and Pat Metheny. Burton recorded duet sets with Chick Corea, Ralph Towner, Steve Swallow, and Paul Bley, and collaborated on an album apiece with Stephane Grappelli and Keith Jarrett. Among his sidemen in the late '70s and '80s were Makoto Ozone, Tiger Okoshi, and Tommy Smith. Very active as an educator at Berklee since joining its faculty in 1971, Burton remained a prominent stylist. He recorded during different periods of his career extensively releasing Like Minds through Concord in 1998.