Panda House 628-634 Commercial Road, London E14 7HS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

15 bus time schedule & line map 15 Trafalgar Square - Blackwall View In Website Mode The 15 bus line (Trafalgar Square - Blackwall) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blackwall: 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Trafalgar Square: 12:10 AM - 11:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 15 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 15 bus arriving. Direction: Blackwall 15 bus Time Schedule 32 stops Blackwall Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Charing Cross Stn / Trafalgar Square (F) 11 Strand, London Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Southampton Street / Covent Garden (A) Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM 390 Strand, London Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Aldwych (D) Friday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM Strand Underpass, London Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:50 PM The Royal Courts Of Justice (L) 265 Strand, London Fetter Lane (E) 167 Fleet Street, London 15 bus Info Direction: Blackwall Ludgate Circus (E) Stops: 32 85 Fleet Street, London Trip Duration: 46 min Line Summary: Charing Cross Stn / Trafalgar Square Ludgate Hill / Old Bailey (G) (F), Southampton Street / Covent Garden (A), Ludgate Hill, London Aldwych (D), The Royal Courts Of Justice (L), Fetter Lane (E), Ludgate Circus (E), Ludgate Hill / Old Bailey St Paul's Cathedral (SK) (G), St Paul's Cathedral (SK), Mansion House Station (ME), Cannon Street (MB), Monument Station (H), Mansion House Station (ME) Great Tower Street (TU), The Tower Of London (Tb), 33 Cannon Street, London Mansell Street (S), Aldgate East Station (H), London -

Limehouse, E1 Ideal for Direct Access to Central London

Limehouse, E1 Ideal for direct access to central London Marlin Limehouse, 577 Commercial Road, London E1 0HJ Telephone: +44 (0)20 7378 4840 Website: www.marlinapartments.com Marlin Limehouse is cleverly situated just outside the hustle and bustle of central London but within easy access to the financial and tourist centres of London. Due to its location just outside the city centre, it is one of our most versatile properties offering high quality serviced accommodation nearby the City, Canary Wharf and the West End. Located moments from the DLR, Limehouse is just five minutes from Bank and Canary Wharf stations. With a supermarket less than one minute’s walk away and a shopping centre located in the nearby Canary Wharf, the area contains all the amenities you will need during your stay. Our high quality serviced apartments at Marlin Limehouse range from studio apartments to spacious two bedroom apartments, each with thoughtful furnishings throughout to maximise the comfort of your stay. y r Studio Apartment Two Bedroom Apartment a v s e p y t t KITCHEN n LIVING e KITCHEN AREA m t r a p a l a u t c a BEDROOM , LIVING AREA y l n Average internal area o BEDROOM 460 sq ft / 43 sq m s e s o p r One Bedroom Apartment u p Average internal area e 750 sq ft / 70 sq m v i BEDROOM t a r t s u l l LIVING i AREA r o f I stayed for three weeks in Marlin e r a Limehouse, and enjoyed every minute of s n KITCHEN a the experience. -

Commercial Road London E1

… 35A COMMERCIAL ROAD LONDON E1 PRIME LONDON DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY … … ALDGATE PLACE (BARRATT) GOODMAN’S ALDGATE ALDGATE FIELDS TOWER EAST WHITECHAPEL STATION 35A (BERKLEY HOMES) (BARRATT) STATION (CROSSRAIL) 500M ALTITUDE ALDGATE THE HERON LIVERPOOL STREET THE SHARD (BARRATT) STATION GHERKIN TOWER STATION … EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Prime city fringe location widely considered one of London’s growth ‘Hotspots’ • Existing building comprises 36 flats (5 x studios & 31 x one beds) totalling approximately 1,236.78 sq m (13,313 sq ft) GIA • Planning consent for change of use of part ground floor to retail (A1); alterations to existing 36 flats and creation of an additional 8 self-contained flats by 4 additional floors comprising a GIA of 4,443.5 sq m (47,830 sq ft). • Pre-application for a full re-development to provide 74 residential units and 250 sq m (2,691 sq ft) of commercial space • Alternative redevelopment potential for a number of uses to include residential, commercial or a mixed-use development subject to the necessary consents • Within the Central Activities Zone and the Aldgate Masterplan • Located within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets benefitting from Aldgate East Underground station and Whitechapel Crossrail station (Opening December 2018) • Vacant possession available on completion Outline for identification purposes only. … 35 A LOCATION CONNECTIVITY DESCRIPTION PLANNING REDEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL LOCAL DEVELOPMENTS LOCATION The property is located on the northern side of Commercial Road, immediately to the west of its junction with Adler Street with direct frontage to both streets. Aldgate is a popular residential area of East London located a short distance from the City and Shoreditch. -

The Road Traffic (Special Parking Area) (London Borough of Tower Hamlets) Order 1994

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1994 No. 1613 ROAD TRAFFIC The Road Traffic (Special Parking Area) (London Borough of Tower Hamlets) Order 1994 Made - - - - 20th June 1994 Laid before Parliament 20th June 1994 Coming into force - - 4th July 1994 Whereas the council of the London borough of Tower Hamlets has applied to the Secretary of State for an order to be made under section 76 of the Road Traffic Act 1991(1) and the Secretary of State has consulted the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis in accordance with section 76(2) of that Act: NOW, the Secretary of State for Transport, in exercise of the powers conferred by section 76(1) and section 77(6) of the Road Traffic Act 1991 and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order:— Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Road Traffic (Special Parking Area) (London Borough of Tower Hamlets) Order 1994 and shall come into force on 4th July 1994. Interpretation 2. In this Order— “the 1984 Act” means the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984(2); “the 1991 Act” means the Road Traffic Act 1991; a reference in the Schedule to a number followed by the letter “m” is a reference to that number of metres; and where a road referred to in the Schedule to this Order (“the main road”) is joined by another road (“the side road”), whether or not that other road is referred to in the Schedule, and the footway to the main road runs on either side of the mouth of the side road, the junction between (1) 1991 c. -

539-541 Commercial Road, E1 539-541 Commercial Road, London E1 0HQ

AVAILABLE TO LET 539-541 Commercial Road, E1 539-541 Commercial Road, London E1 0HQ Retail for rent, 2,001 sq ft, £65,000 per annum Iftakhar Khan [email protected] To request a viewing call us on 0203 911 3666 For more information visit https://realla.co/m/41379-539-541-commercial-road-e1-539-541-commercial-road 539-541 Commercial Road, E1 539-541 Commercial Road, London E1 0HQ To request a viewing call us on 0203 911 3666 A1 Retail/Showroom Unit - Limehouse Retail Opportunity The site is located on Commercial Road(A13), close to The Troxy and within a few minutes walk to Limehouse station (C2C and DLR). Numerous bus routes also serve this section of Commercial Road - one of the main road routes connecting East London to the City and Canary Wharf. Part of a new mixed use development on the junction of Commercial Road & Head Street – just west of the Limehouse Link tunnel. Highlights Ceiling heights ranging from 3.2 metre to 4.06 metre Ideal for a range of A1 uses –A2, B1 & D1 uses also considered subject to necessary consents 2001 sq ft floor area divided over ground floor, rear ground floor plus More information basement storage Primary ground floor retail area 912 sq ft, Raised ground floor office area 314 sq ft Rear ground floor storage area 775 sq ft Visit microsite The building is undergoing major refurbishment https://realla.co/m/41379-539-541-commercial-road-e1-539-541- Property details commercial-road Rent £65,000 per annum Contact us Building type Retail Stirling Ackroyd 40 Great Eastern Street, London EC2A 3EP Planning -

LTHCT Call for Trustees

Open Call: New Board Trustees for Limehouse Town Hall Consortium Trust Limehouse Town Hall Consortium Trust (LTHCT) is currently looking to add new trustees to its board to help assist in the oversight and operations of Limehouse Town Hall. This is an exciting time for LTHCT as we are entering a period of making significant improvements to Limehouse Town Hall and the Trust. In addition to maintaining our civic and community engagement efforts and modelling sustainable and ethical practices in the cultural industries in London, LTHCT is embarking on major fundraising bids to enhance the building’s existing infrastructure and make it more accommodating to residents and visitors with accessibility needs. In addition, we are looking to rethink and reorganise how the building is run and administered. New trustees will play an integral role in shaping the future of LTHCT. We are especially interested in encouraging expressions of interest from: • Local residents and workers in Tower Hamlets; • Individuals already familiar with the activities of Limehouse Town Hall. • Artists, activists and community organisers with experience in similar and likeminded building-based organisations, charities and co-operatives; • Individuals with experience or training in law, civic policy, critical urban development, alternative economies, social organising, fundraising, conservation of historic buildings, and community engagement, marketing and communications. About Limehouse Town Hall Consortium Trust Limehouse Town Hall Consortium Trust (LTHCT) is a charity founded in 2004 as a resource for artists, community arts organisations and cultural producers. It has an annual operating budget of £70,000 and served 17,000 people in 2018/19. It’s mission is to maintain, improve and promote Limehouse Town Hall’s use to advance public education and involvement in arts and culture and restore the building to its place as an active participant in Limehouse, the east end of London and beyond. -

A13 Commercial Road Consultation Report V04.Pdf

Proposed changes to A13 Commercial Road between New Road and Jubilee Street Response to consultation July 2016 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 2 1 Background .................................................................................................................. 5 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 3 The consultation ......................................................................................................... 10 4 Overview of consultation responses ........................................................................... 14 5 Conclusion and next steps ......................................................................................... 33 Appendix A – TfL response to issues commonly raised ........................................................ 33 Appendix B – Copy of consultation letter .............................................................................. 33 Appendix C – Letter distribution area .................................................................................... 48 Appendix D – List of stakeholders consulted ........................................................................ 49 Executive Summary About the consultation: Between 29 January and 11 March 2016, we consulted on proposals to improve safety, journey time reliability and the urban realm on the A13 Commercial Road between -

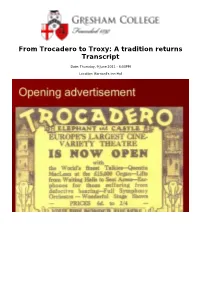

From Trocadero to Troxy: a Tradition Returns Transcript

From Trocadero to Troxy: A tradition returns Transcript Date: Thursday, 9 June 2011 - 6:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 9 June 2011 From Trocadero to Troxy: A tradition returns John Abson and Richard HILLS FRCO Introduction (John Abson) The Hyams family Our story starts with three brothers - Phil, Sid and Mick Hyams. The eldest, Phil, started in the trade by working as a teenager in the new Popular cinema in the Commercial Road, Stepney. The new Popular was partly financed by the brothers' father, Hyam Hyams, a Russian immigrant and nephew of the founders of the well-known London chain of Grodzinski's bakeries. Phil was joined by his brother Sid and built up a small circuit that included the Canterbury in Westminster Bridge Road. In 1927 the Hyams converted a vast tram shed into their first super cinema: the 2,700 seat Broadway at Stratford, east London. This was also the Hyams first contact with the Wurlitzer pipe organ; the Broadway was equipped with one of this country’s early examples and the experience no doubt inspired what today would be called ‘brand loyalty’, as this story tells. Thanks to a versatile and gifted architect, George Coles, the Broadway auditorium looked palatial and Coles went on to design all the cinemas the Hyams initiated. Coles was credited with the designs for over 80 cinemas, including many for Oscar Deutsch’s Odeon chain. In 1928, the Hyams sold their circuit to the newly formed Gaumont British combine, then started afresh as H&G Kinemas in partnership with Major A.J. -

St Anne's Church

St Anne’s Church St Anne’s Church Conservation Area 1. Character Appraisal 2. Management Guidelines London Borough of Tower Hamlets Adopted by Cabinet: 4th November 2009 St Anne’s Church Conservation Area Page 1 of 21 St Anne’s Church Introduction Conservation Areas are parts of our local environment with special architectural or historic qualities. They are created by the Council, in consultation with the local community, to preserve and enhance the specific character of these areas for everybody. This guide has been prepared for the following purposes: To comply with the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. Section 69(1) states that a conservation area is “an area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance.” To provide a detailed appraisal of the area’s architectural and historic character. To help those who have an interest in the area to understand the quality of the built environment and how they can protect, contribute to and enhance it. To provide an overview of planning policy and propose management guidelines on how this character should be preserved and enhanced in the context of appropriate ongoing change. Many significant sites within the St Anne’s Church Conservation Area are currently undertaking redevelopment which will fundamentally alter the character of this part of London, in respect to the setting of St Anne’s Church and churchyard. Because of this significant ongoing change, this document will be revised once construction has settled, and the new character of the Limehouse area has established itself. -

The Jews in London 1695 & 1895

M.Sc. in Advanced Architectural Studies • The Bartlett Graduate School • University College London Poor Boy, from East End 1888 by William Fishman, 1988 A Study of the Spatial Characteristics of The Jews In London 1695 & 1895 Laura Vaughan • Thesis • September 1994 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their help during the past year: Ms. Rickie Burman, Curator of the London Museum of Jewish History at the Steinberg Centre for Judaism. Dr. John Klier, Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies, University College London. Dr. David Cezarani, Weiner Library and Jewish Historical Society. I would also like to express my gratitude to Professor Bill Hillier, Dr. Julienne Hanson and Mr. Alan Penn who gave me much inspiration and guidance throughout the course. And lastly to Neil for acting as my ‘layman’. Abstract This paper suggests that the settlement pattern of Jews in London is in a distinct cluster, but contradicts the accepted belief about the nature of the ‘ghetto’; finding that the traditional conception of the ‘ghetto’, as an enclosed, inward-looking immigrant quarter is incorrect in this case. It is shown that despite the fact that the Jews sometimes constituted up to 100% of the population of a street, that in general, the greater the concentration of Jews in a street, the better connected (more ‘integrated’) the street was into the main spatial structure of the city. It is also suggested here that the Jewish East End worked both as an internally strong structure of space, with local institutions relating to and reinforcing the local pattern of space; and also externally, with strong links tying the Jewish East End with its host society. -

Commercial Rd 767-785 , Viability Report, 1016

Guy Ziser Wild Orchid Property Ltd 9 Hampstead West 224 Iverson Road London NW6 2HL 24 October 2016 FOI Exemption Section 41/43(2) Private & Confidential Dear Mr Ziser 767-785 COMMERCIAL ROAD, LONDON, E14 7HG VIABILITY ASSESSMENT 1. INTRODUCTION Pre-application advice from the Council dated 6 January 2016 noted on page 3 that “the proposal as it stands has attracted objections from the council’s housing team due to the proposal not offering any accommodation which would qualify as affordable housing and the potential loss of opportunity to develop the site for affordable housing.” A Viability Assessment has therefore been produced to demonstrate the affordable housing contribution if any that the scheme is able to provide viably, as sought by the Council’s ‘Managing Development Document, Development Plan Document’ (April 2013), page 28, paragraph 3.6. The application site is located on the Commercial Road, bounded by the Limehouse Cut canal to the rear. There are 4 parts to the site, which are summarised as follows: • Corner Site : 767 Commercial Road is an existing tyre and exhaust centre with associated vehicular parking. • West Site : 769-775 Commercial Road, a vacant triangular area of cleared land on the western part of the site, with timber hoarding. • Central Site : 777-783 Commercial Road is occupied by a two storey Grade II listed Victorian warehouse with basement. The warehouse was originally built in 1869 for sail making and chandling before being used for the engineering and manufacture of steam pumps from 1889 to the late 1990s, since when it has been vacant. -

38-44 White Horse Road and 605-623 Commercial Road, London

DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE 9th July 2020 Report of the Corporate Director of Place Classification: Unrestricted Application for Planning Permission Click here for case file Reference PA/19/00669 Site 38-44 White Horse Road and 605-623 Commercial Road, London Ward Limehouse Proposal Development of mixed-use scheme up to 5 storeys comprising 38 residential units, 740sqm flexible commercial floor space (Use Class A1, A2, A3, B1, D1, and D2) at basement and ground floor level, and associated amenity space and cycle storage. Summary Approve planning permission subject to conditions and a legal agreement. Recommendation Applicant Limehouse Equity Limited Architect ROK Planning Case Officer Shahara Ali-Hempstead Key dates - Application registered as valid on 15/05/2019 - Public consultation finished on 27/02/2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The application site contains a number of single and two storey post-war buildings and warehouses which were last used as retail and storage space. The site lies within York Square Conservation Area and Limehouse Neighbourhood Centre. The proposed development comprises the erection of part 3, 4 and 5 storey buildings which would provide 38 residential units and 740 square metres of commercial space at ground level. In land use terms the mixed use scheme would contribute to the broader regeneration of the area and provides a significant opportunity to enhance the derelict site by bringing back commercial units and providing an active frontage along Commercial Road. The scheme would provide 40% affordable housing by habitable room, including a variety of unit typologies across both affordable rented and intermediate tenures. Residential dwellings would provide a good standard of internal accommodation and generous private and communal amenity space and child play space.