Stirling Range National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tabled Paper – Legislative Council Question on Notice 3064

TABLED PAPER – LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL QUESTION ON NOTICE 3064 A SUMMARY OF COMPLETED IMPROVEMENTS AND COSTS IN SOUTH WEST NATIONAL PARKS 2012-13 Park Improvements Cost Yalgorup National Park Martins Tank campground upgrade $673,425 Lane Poole Reserve Nanga Brook campground upgrade $106,441 Lane Poole Reserve River Road bridge replacement $75,000 Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park Sugarloaf Rock redevelopment $300,984 Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park Lefthanders access road sealing $200,000 Bramley National Park Wharncliffe Mill upgrade $38,761 Wiltshire Butler National Park Crouch Road bridge replacement $19,054 D’Entrecasteaux National Park Donnelly River Boat Landing site upgrade $23,974 Mt Frankland National Park Mt Frankland Wilderness lookout $200,000 Walpole-Nornalup National Park Coalmine Beach finger jetty $156,934 Walpole-Nornalup National Park Coalmine Beach small boat facilities $316,654 Walpole-Nornalup National Park Rocky Crossing intersection upgrade $30,000 D’Entrecasteaux National Park Bottleneck Bay and Cliffy Head car park upgrade $20,000 Mt Frankland North National Park Shedick Road bridge replacement $75,000 Porongurup National Park Castle Rock day use area upgrade $525 Porongurup National Park Porongurup scenic drive upgrade $25,000 Torndirrup National Park Gap-Natural Bridge upgrade $271,302 Fitzgerald River National Park Point Ann upgrade $159,417 TOTAL $2,692,471 2013-14 Park Improvements Cost Yalgorup National Park Martins Tank campground upgrade $43,286 Yalgorup National Park Martins Tank campground upgrade $522,788 -

Great Southern Recovery Plan

Great Southern Recovery Plan The Great Southern Recovery Plan is part of the next step in our COVID-19 journey. It’s part of WA’s $5.5 billion overarching State plan, focused on building infrastructure, economic, health and social outcomes. The Great Southern Recovery Plan will deliver a pipeline of jobs in sectors including construction, manufacturing, tourism and hospitality, renewable energy, education and training, agriculture, conservation and mining. WA’s recovery is a joint effort, it’s about Government working with industry together. We managed the pandemic together as a community. Together, we will recover. Investing in our Schools and Rebuilding our TAFE Sector • $6.3 million for a new Performing Arts centre at Albany Senior High School • $1.1 million for refurbishments at North Albany Senior High School including the visual arts area and specialist subject classrooms • $17 million to South Regional TAFE’s Albany campus for new trade workshops, delivering training in the automotive, engineering and construction industries • $25 million for free TAFE short courses to upskill thousands of West Australians, with a variety of free courses available at South Regional TAFE’s Albany, Denmark, Katanning and Mount Barker campuses • $32 million to expand the Lower Fees, Local Skills program and significantly reduce TAFE fees across 39 high priority courses • $4.8 million for the Apprenticeship and Traineeship Re-engagement Incentive that provides employers with a one-off payment of $6,000 for hiring an apprentice and $3,000 for hiring -

Downloading Or Purchasing Online At

On-farm Evaluation of Grafted Wildflowers for Commercial Cut Flower Production OCTOBER 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 11/149 On-farm Evaluation of Grafted Wildflowers for Commercial Cut Flower Production by Jonathan Lidbetter October 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 11/149 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-000509 © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-328-4 ISSN 1440-6845 On-farm Evaluation of Grafted Wildflowers for Commercial Cut Flower Production Publication No. 11/149 Project No. PRJ-000509 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. This publication is copyright. -

Final Annual Report 2005-2006

About us Contents MINISTER FOR THE Executive Director’s review 2 ENVIRONMENT About us 4 In accordance with Our commitment 4 Section 70A of the Our organisation 7 Financial Administration The year in summary 12 and Audit Act 1985, I submit for your Highlights of 2005-2006 12 Strategic Planning Framework 16 information and presentation to Parliament What we do 18 the final annual report of Nature Conservation – Service 1 18 the Department of Sustainable Forest Management – Service 2 65 Conservation and Land Performance of Statutory Functions by the Conservation Commission Management. of Western Australia (see page 194) – Service 3 Parks and Visitor Services – Service 4 76 Astronomical Services – Service 5 112 General information 115 John Byrne Corporate Services 115 REPORTING CALM-managed lands and waters 118 OFFICER Estate map 120 31 August 2006 Fire management services 125 Statutory information 137 Public Sector Standards and Codes of Conduct 137 Legislation 138 Disability Services 143 EEO and diversity management 144 Electoral Act 1907 145 Energy Smart 146 External funding, grants and sponsorships 147 Occupational safety and health 150 Record keeping 150 Substantive equality 151 Waste paper recycling 151 Publications produced in 2005-2006 152 Performance indicators 174 Financial statements 199 The opinion of the Auditor General appears after the performance indicators departmentofconservationandlandmanagement 1 About us Executive Director’s review The year in review has proved to be significant for the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) for the work undertaken and because it has turned out to be the Department’s final year of operation. The Minister for the Environment announced in May 2006 that CALM would merge with the Department of Environment on 1 July 2006 to form the Department of Environment and Conservation. -

Stirling Range

ongoing fox control and native animal recovery program. recovery animal native and control fox ongoing Western Shield Western , an an , and Zoo Perth with conjunction in conducted park. This has been possible due to a captive breeding program program breeding captive a to due possible been has This park. thought to be extinct) have been reintroduced into areas of the the of areas into reintroduced been have extinct) be to thought them. Numbats (WA’s official mammal emblem) and dibblers (once (once dibblers and emblem) mammal official (WA’s Numbats defined area, either on particular peaks or in the valleys between between valleys the in or peaks particular on either area, defined River little bat and lesser long-eared bat. long-eared lesser and bat little River level on acid sandy clay soil. Each species occurs in a well- well- a in occurs species Each soil. clay sandy acid on level as it is home to a powerful ancestral being. ancestral powerful a to home is it as echidna, tammar wallaby, western pygmy possum plus the King King the plus possum pygmy western wallaby, tammar echidna, Mountain bells are usually found above the 300-metre contour contour 300-metre the above found usually are bells Mountain significance to traditional Aboriginal people of the south-west south-west the of people Aboriginal traditional to significance dunnarts, honey possum, mardo (antechinus), short-beaked short-beaked (antechinus), mardo possum, honey dunnarts, outside Stirling Range. Stirling outside Bluff Knoll (Bular Mial) continues to be of great spiritual spiritual great of be to continues Mial) (Bular Knoll Bluff bush rat, common brushtail possum, fat-tailed and white-tailed white-tailed and fat-tailed possum, brushtail common rat, bush have been identified in the park and only one of these is found found is these of one only and park the in identified been have Other mammals found in the range include the ash-grey mouse, mouse, ash-grey the include range the in found mammals Other worked on farms and lived on settlements or in missions. -

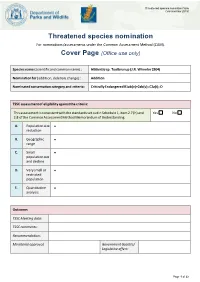

Threatened Species Nomination Form (Version Nov 2015)

Threatened species nomination form (Version Nov 2015) Threatened species nomination For nominations/assessments under the Common Assessment Method (CAM). Cover Page (Office use only) Species name (scientific and common name): Hibbertia sp. Toolbrunup (J.R. Wheeler 2504) Nomination for (addition, deletion, change): Addition Nominated conservation category and criteria: Critically Endangered B1ab(v)+2ab(v); C2a(i); D TSSC assessment of eligibility against the criteria: This assessment is consistent with the standards set out in Schedule 1, item 2.7 (h) and Yes No 2.8 of the Common Assessment Method Memorandum of Understanding. A. Population size reduction B. Geographic range C. Small population size and decline D. Very small or restricted population E. Quantitative analysis Outcome: TSSC Meeting date: TSSC comments: Recommendation: Ministerial approval: Government Gazette/ Legislative effect: Page 1 of 22 Nomination summary (to be completed by nominator) Current conservation status Scientific name: Hibbertia sp. Toolbrunup (J.R. Wheeler 2504) Common name: None Family name: Dilleniaceae Fauna Flora Nomination for: Listing Change of status Delisting Yes No Is the species currently on any conservation list, either in WA, Australia or Internationally? If Yes; complete the If No; go to the next following table question Date listed or Listing category i.e. Listing criteria i.e. Jurisdiction List or Act name assessed critically endangered B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii) International IUCN Red List National EPBC Act State of WA WC Act Assessed Critically -

Focusing on the Landscape Biodiversity in Australia’S National Reserve System Contents

Focusing on the Landscape Biodiversity in Australia’s National Reserve System Contents Biodiversity in Australia’s National Reserve System — At a glance 1 Australia’s National Reserve System 2 The Importance of Species Information 3 Our State of Knowledge 4 Method 5 Results 6 Future Work — Survey and Reservation 8 Conclusion 10 Summary of Data 11 Appendix Species with adequate data and well represented in the National Reserve System Flora 14 Fauna 44 Species with adequate data and under-represented in the National Reserve System Flora 52 Fauna 67 Species with inadequate data Flora 73 Fauna 114 Biodiversity in Australia’s National Reserve System At a glance • Australia’s National Reserve System (NRS) consists of over 9,000 protected areas, covering 89.5 million hectares (over 11 per cent of Australia’s land mass). • Australia is home to 7.8 per cent of the world’s plant and animal species, with an estimated 566,398 species occurring here.1 Only 147,579 of Australia’s species have been formally described. • This report assesses the state of knowledge of biodiversity in the National Reserve System based on 20,146 terrestrial fauna and flora species, comprising 54 per cent of the known terrestrial biodiversity of Australia. • Of these species, 33 per cent (6,652 species) have inadequate data to assess their reservation status. • Of species with adequate data: • 23 per cent (3,123 species) are well represented in the NRS • 65 per cent (8,692 species) are adequately represented in the NRS • 12 per cent (1,648 species) are under- represented in the NRS 1 Chapman, A.D. -

Stirling Range Beard Heath (Leucopogon Gnaphalioides) Interim Recovery Plan 2013-2017

INTERIM RECOVERY PLAN NO. 334 STIRLING RANGE BEARD HEATH (Leucopogon gnaphalioides) INTERIM RECOVERY PLAN 2013-2018 February 2013 Department of Environment and Conservation Kensington Interim Recovery Plan for Leucopogon gnaphalioides FOREWORD Interim Recovery Plans (IRPs) are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) Policy Statements Nos. 44 and 50. Note: the Department of CALM formally became the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) in July 2006. DEC will continue to adhere to these Policy Statements until they are revised and reissued. Plans outline the recovery actions that are required to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. DEC is committed to ensuring that Threatened taxa are conserved through the preparation and implementation of Recovery Plans (RPs) or IRPs, and by ensuring that conservation action commences as soon as possible and, in the case of Critically Endangered taxa, always within one year of endorsement of that rank by the Minister. This plan will operate from February 2013 to January 2018 but will remain in force until withdrawn or replaced. It is intended that, if the taxon is still ranked as Critically Endangered, this plan will be reviewed after five years and the need for further recovery actions assessed. This plan was given regional approval on 14TH January 2013 and was approved by the Director of Nature Conservation on 7th February 2013. The provision of funds identified in this plan is dependent on budgetary and other constraints affecting DEC, as well as the need to address other priorities. -

Stirling Range

as it is home to a powerful ancestral being. ancestral powerful a to home is it as significance to traditional Aboriginal people of the south-west south-west the of people Aboriginal traditional to significance Bluff Knoll (Bular Mial) continues to be of great spiritual spiritual great of be to continues Mial) (Bular Knoll Bluff worked on farms and lived on settlements or in missions. in or settlements on lived and farms on worked Displaced from their traditional land, many Noongar people people Noongar many land, traditional their from Displaced transported through the range to the port in Albany. in port the to range the through transported raising livestock. Cattle, sheep, wool and sandalwood were were sandalwood and wool sheep, Cattle, livestock. raising European settlers arrived and took up land, creating farms and and farms creating land, up took and arrived settlers European Common mountain bell mountain Common bell mountain Yellow bell Cranbrook fruit while men hunted kangaroos, wallabies and other animals. other and wallabies kangaroos, hunted men while fruit people. Women gathered roots, seeds and and seeds roots, gathered Women people. (Nyoongar) Noongar for populations through control of foxes and feral cats. feral and foxes of control through populations The lowlands surrounding the peaks were important sources of food food of sources important were peaks the surrounding lowlands The wildlife conservation program that aims to recover native animal animal native recover to aims that program conservation wildlife either on particular peaks or in the valleys between them. between valleys the in or peaks particular on either moving around the mountains’ – a frequently seen occurrence. -

Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014–15 Annual Report Acknowledgments

Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014–15 Annual Report Acknowledgments This report was prepared by the Public About the Department’s logo Information and Corporate Affairs Branch of the Department of Parks and Wildlife. The design is a stylised representation of a bottlebrush, or Callistemon, a group of native For more information contact: plants including some found only in Western Department of Parks and Wildlife Australia. The orange colour also references 17 Dick Perry Avenue the WA Christmas tree, or Nuytsia. Technology Park, Western Precinct Kensington Western Australia 6151 WA’s native flora supports our diverse fauna, is central to Aboriginal people’s idea of country, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre and attracts visitors from around the world. Western Australia 6983 The leaves have been exaggerated slightly to suggest a boomerang and ocean waves. Telephone: (08) 9219 9000 The blue background also refers to our marine Email: [email protected] parks and wildlife. The design therefore symbolises key activities of the Department The recommended reference for this of Parks and Wildlife. publication is: Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014–15 The logo was designed by the Department’s Annual Report, Department of Parks and senior graphic designer and production Wildlife, 2015 coordinator, Natalie Curtis. ISSN 2203-9198 (Print) ISSN 2203-9201 (Online) Front cover: Granite Skywalk, Porongurup National Park. September 2015 Photo – Andrew Halsall Copies of this document are available Back cover: Osprey Bay campground at night, in alternative formats on request. Cape Range National Park. Photo – Peter Nicholas/Parks and Wildlife Sturt’s desert pea, Millstream Chichester National Park. -

Park Visitor Fees for Example, Two Adults Camping at Cape Le Grand National Park for Four Open Daily 9Am to 4.15Pm

Camping fees Attraction fees Camping fees must be paid for each person for every night they stay. Please note that park passes do not apply to the following managed Entrance fees must also be paid, (if they apply) but only on the day you attractions. arrive. Parks with entrance fees are listed in this brochure. Tree Top Walk Park visitor fees For example, two adults camping at Cape Le Grand National Park for four Open daily 9am to 4.15pm. Extended hours 8am to 5.15pm from nights will pay: 26 December to 26 January. Closed Christmas Day and during hazardous conditions. 2 adults x 4 nights x $11 per adult per night plus $13 entrance = $101 • Adult $21 If you hold a park pass you only need to pay for camping. • Concession cardholder (see `Concessions´) $15.50 For information on campgrounds and camp site bookings visit • Child (aged 6 to 15 years) $10.50 parkstay.dbca.wa.gov.au. • Family (2 adults, 2 children) $52.50 Camping fees for parks and State forest No charge to walk the Ancient Empire. Without facilities or with basic facilities Geikie Gorge National Park boat trip Boat trips depart at various days and times from the end of April • Adult $8 to November. Please check departure times with the Park's and Wildlife • Concession cardholder per night (see `Concessions´) $6 Service Broome office on (08) 9195 5500. • Child per night (aged 6 to 15 years) $3 • Adult $45 With facilities such as ablutions or showers, barbeque shelters • Concession cardholder (see `Concessions´) $32 or picnic shelters • Child (aged 6 to 15 years) $12 • Adult per night $11 • Family (2 adults, 2 children) $100 • Concession cardholder per night (see `Concessions´) $7 Dryandra Woodland • Child per night (aged 6 to 15 years) $3 Fully guided night tours of Barna Mia nocturnal wildlife experience on King Leopold Ranges Conservation Park, Purnululu Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays. -

National, Marine and Regional Parks

National, marine and regional parks Visitor guide This document is available in alternative formats on request. Information current at June 2014. Department of Parks and Wildlife dpaw.wa.gov.au parks.dpaw.wa.gov.au 20140415 0614 35M William Bay National Park diseases (including fish kills) and illegal fishing. Freecall 1800 815 507 815 1800 Freecall fishing. illegal and kills) fish (including diseases - To report sightings or evidence of aquatic pests, aquatic aquatic pests, aquatic of evidence or sightings report To - Fishwatch Freecall 1800 449 453 449 1800 Freecall - For reporting illegal wildlife activity. activity. wildlife illegal reporting For - Watch Wildlife shop.dpaw.wa.gov.au (08) 9474 9055 9055 9474 (08) Buy books, maps and and maps books, Buy LANDSCOPE subscriptions online. online. subscriptions LANDSCOPE - For sick and injured native wildlife. wildlife. native injured and sick For - helpline WILDCARE Publications WA Naturally WA Walpole (08) 9840 0400 9840 (08) Walpole NATURALLY WA Geraldton (08) 9921 5955 5955 9921 (08) Geraldton NATURALLY WA parks.dpaw.wa.gov.au/park-brochures Wanneroo (08) 9405 0700 0700 9405 (08) Wanneroo credited. otherwise those except Wilkins/DEC, Peter by are photos All l htsaeb ee ikn/E,ecp hs tews credited. otherwise those except Wilkins/DEC, Peter by are photos All RECYCLE RECYCLE laertr natdbohrst itiuinpoints distribution to brochures unwanted return Please laertr natdbohrst itiuinpoints distribution to brochures unwanted return Please Information current at October 2009 October at current Information rn cover Front rn cover Front ht odnRoberts/DEC Gordon – Photo ht odnRoberts/DEC Gordon – Photo izeadRvrNtoa Park. National River Fitzgerald izeadRvrNtoa Park.