Hallucinogenic Mushrooms in Mexico: an Overview1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Studies on Psilocybe from the Caribbean, Central America and South America, with Descriptions of New Species and Remarks to New Records

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Sydowia Jahr/Year: 2009 Band/Volume: 61 Autor(en)/Author(s): Guzman Gaston, Ramirez-Guillen Florencia, Horak Egon, Halling Roy Artikel/Article: Further studies on Psilocybe from the Caribbean, Central America and South America, with descriptions of new species and remarks to new records. 215-242 ©Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges.m.b.H., Horn, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Further studies on Psilocybe from the Caribbean, Central America and South America, with descriptions of new species and remarks to new records. Gastón Guzmán1*, Egon Horak2, Roy Halling3, Florencia Ramírez-Guillén1 1 Instituto de Ecología, Apartado Postal 63, Xalapa 91000, Mexico. 2 Nikodemweg 5, AT-6020 Innsbruck, Austria. 3 New York Botanical Garden, New York, Bronx, NY 10458-5126, USA.leiferous Guzmán G., Horak E., Halling R. & Ramírez-Guillén F. (2009). Further studies on Psilocybe from the Caribbean, Central America and South America, with de- scriptions of new species and remarks to new records. – Sydowia 61 (2): 215–242. Seven new species of Psilocybe (P. bipleurocystidiata, P. multicellularis, P. ne- oxalapensis, P. rolfsingeri, P. subannulata, P. subovoideocystidiata and P. tenuitu- nicata are described and illustrated. Included are also discussion and remarks refer- ring to new records of the following taxa: P. egonii, P. fagicola, P. montana, P. mus- corum, P. plutonia, P. squamosa, P. subhoogshagenii, P. subzapotecorum, P. wright- ii, P. yungensis and P. zapotecoantillarum. Thirteen of the enumerated species are hallucinogenic. Key words: Basidiomycotina, Strophariaceae, Agaricales, bluing, not bluing. In spite of numerous studies on the genus Psilocybe in the Carib- bean, Central America and South America (Singer & Smith 1958; Singer 1969, 1977, 1989; Guzmán 1978, 1983, 1995; Pulido 1983, Sáenz & al. -

The Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: Diversity, Traditions, Use and Abuse with Special Reference to the Genus Psilocybe

11 The Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: Diversity, Traditions, Use and Abuse with Special Reference to the Genus Psilocybe Gastón Guzmán Instituto de Ecologia, Km 2.5 carretera antigua a Coatepec No. 351 Congregación El Haya, Apartado postal 63, Xalapa, Veracruz 91070, Mexico E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The traditions, uses and abuses, and studies of hallucinogenic mush- rooms, mostly species of Psilocybe, are reviewed and critically analyzed. Amanita muscaria seems to be the oldest hallucinogenic mushroom used by man, although the first hallucinogenic substance, LSD, was isolated from ergot, Claviceps purpurea. Amanita muscaria is still used in North Eastern Siberia and by some North American Indians. In the past, some Mexican Indians, as well as Guatemalan Indians possibly used A. muscaria. Psilocybe has more than 150 hallucinogenic species throughout the world, but they are used in traditional ways only in Mexico and New Guinea. Some evidence suggests that a primitive tribe in the Sahara used Psilocybe in religions ceremonies centuries before Christ. New ethnomycological observations in Mexico are also described. INTRODUCTION After hallucinogenic mushrooms were discovered in Mexico in 1956-1958 by Mr. and Mrs. Wasson and Heim (Heim, 1956; Heim and Wasson, 1958; Wasson, 1957; Wasson and Wasson, 1957) and Singer and Smith (1958), a lot of attention has been devoted to them, and many publications have 257 flooded the literature (e.g. Singer, 1958a, b, 1978; Gray, 1973; Schultes, 1976; Oss and Oeric, 1976; Pollock, 1977; Ott and Bigwood, 1978; Wasson, 1980; Ammirati et al., 1985; Stamets, 1996). However, not all the fungi reported really have hallucinogenic properties, because several of them were listed by erroneous interpretation of information given by the ethnic groups originally interviewed or by the bibliography. -

New Species of Psilocybe from Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia and New Zealand

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Sydowia Jahr/Year: 1978/1979 Band/Volume: 31 Autor(en)/Author(s): Guzman Gaston, Horak Egon Artikel/Article: New Species of Psilocybe from Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia and New Zealand. 44-54 ©Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges.m.b.H., Horn, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at New Species of Psilocybe from Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia and New Zealand G. GUZMAN Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biologicas, I. P. N., A. P. 26-378, Mexico 4, D. F. and E. HORAK Institut Spezielle Botanik, ETHZ, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz Zusammenfassung. Aus Auslralasien (Papua New Guinea, Neu Kaledonien und Neu Seeland) werden 6 neue Arten von Psilocybe (P. brunneo- cystidiata, P. nothofagensis, P. papuana, P. inconspicua, P. neocaledonica and P. novae-zelandiae) beschrieben. Zudem wird die systematische Stellung dieser Taxa bezüglich P. montana, P. caerulescens, P. mammillata, P. yungensis und anderer von GUZMÄN in den tropischen Wäldern von Mexiko gefundenen Psilocybe-Arten diskutiert. Between 1967 and 1977 one of the authors (HORAK) made several collections of Psilocybe in Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia and New Zealand. After studying the material it was surprising to note that all fungi collected do represent new species. This fact may indicate the high grade of endemism of the fungus flora on the Australasian Islands. Nevertheless, the new taxa described have interesting taxo- nomic relationships with species known from tropical America and temperate Eurasia. These connections are discussed in the text. Concerning Psilocybe only three records are published so far from the before mentioned Australasian region: 1. -

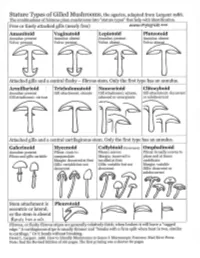

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Psilocybin Mushrooms Fact Sheet

Psilocybin Mushrooms Fact Sheet January 2017 What are psilocybin, or “magic,” mushrooms? For the next two decades thousands of doses of psilocybin were administered in clinical experiments. Psilocybin is the main ingredient found in several types Psychiatrists, scientists and mental health of psychoactive mushrooms, making it perhaps the professionals considered psychedelics like psilocybin i best-known naturally-occurring psychedelic drug. to be promising treatments as an aid to therapy for a Although psilocybin is considered active at doses broad range of psychiatric diagnoses, including around 3-4 mg, a common dose used in clinical alcoholism, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorders, ii,iii,iv research settings ranges from 14-30 mg. Its obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression.xiii effects on the brain are attributed to its active Many more people were also introduced to psilocybin metabolite, psilocin. Psilocybin is most commonly mushrooms and other psychedelics as part of various found in wild or homegrown mushrooms and sold religious or spiritual practices, for mental and either fresh or dried. The most popular species of emotional exploration, or to enhance wellness and psilocybin mushrooms is Psilocybe cubensis, which is creativity.xiv usually taken orally either by eating dried caps and stems or steeped in hot water and drunk as a tea, with Despite this long history and ongoing research into its v a common dose around 1-2.5 grams. therapeutic and medical benefits,xv since 1970 psilocybin and psilocin have been listed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, the most heavily Scientists and mental health professionals criminalized category for drugs considered to have a consider psychedelics like psilocybin to be “high potential for abuse” and no currently accepted promising treatments as an aid to therapy for a medical use – though when it comes to psilocybin broad range of psychiatric diagnoses. -

NHBSS 041 2E Hilton Proced

NAT. NAT. HIST. BUL L. SIAM Soc. 41: 75-92 , 1993 PROCEDURES IN THAI ETHNOMYCOLOGY Roger N. Hilton* and Pannee Dhitaphichit** CONTENTS Page Page 守,守戸、 Introduction Introduction Jζ The The Nature of Fungi Fり勺 Mycological Mycological Literature 守fF 勾f。。。。凸ツ口ツ勺 Early Early R釘 ords Collecting Collecting 勺F Romanization Romanization of Local Languages 守''巧 Fungi Fungi as Food /0000000000 Fungi Fungi as Food 島10difiers 4q4 Poisonous Poisonous Fungi 勾 Medicinal Medicinal Fungi 3ζJζJ Hallucinogenic Hallucinogenic Fungi Fungus Fungus Structural Material Club Club heads. Fungal felt. Rhizomorph skirts. Miscellaneous Miscellaneous 0δ0606ζUζU00 References References Appendix Appendix INTRODUCTION In In assessing biological resources of rural communities anthropologists have paid due attention attention to plants and to animals. The sCIences of ethnobotany and ethnozoology are well- established. established. However , the third kingdom of living things , the Fungi , has been neglected. This This is partly because its prominent members are more evanescent than plants and animals. But a contributing factor is the unfamiliarity of these organisms , so that untrained field investigators investigators have no idea how to set about collecting and naming them. This paper is designed designed to give some of the uses to which fungi are known to be put , to explain how to collect collect them ,and to draw attention to publications that may be used. Formerly * Formerly Botany Department ,University of Westem Australia. Present address: 62 Viewway ,Nedlands , W.A. W.A. 6009 ,Australia. 判 Department of Applied Biology , King Mongku t' s Institute of Technology ,Ladkrabang ,Bangkok 10520 75 75 76 ROOER N. HILTON AND PANNEE DHITAPHICHIT It It could provide a background for looking into the references to fungi in the literature of of Southeast Asia. -

Mycological Investigations on Teonanacatl the Mexican Hallucinogenic Mushroom

Mycological investigations on Teonanacatl, the mexican hallucinogenic mushroom by Rolf Singer Part I & II Mycologia, vol. 50, 1958 © Rolf Singer original report: https://mycotek.org/index.php?attachments/mycological-investigations-on-teonanacatl-the-mexian-hallucinogenic-mushroom-part-i-pdf.511 66/ Table of Contents: Part I. The history of Teonanacatl, field work and culture work 1. History 2. Field and culture work in 1957 Acknowledgments Literature cited Part II. A taxonomic monograph of psilocybe, section caerulescentes Psilocybe sect. Caerulescentes Sing., Sydowia 2: 37. 1948. Summary or the stirpes Stirps. Cubensis Stirps. Yungensis Stirps. Mexicana Stirps. Silvatica Stirps. Cyanescens Stirps. Caerulescens Stirps. Caerulipes Key to species of section Caerulescentes Stirps Cubensis Psilocybe cubensis (Earle) Sing Psilocybe subaeruginascens Höhnel Psilocybe aerugineomaculans (Höhnel) Stirps Yungensis Psilocybe yungensis Singer and Smith Stirps Mexicana Psilocybe mexicana Heim Stirps Silvatica Psilocybe silvatica (Peck) Psilocybe pelliculosa (Smith) Stirps Cyanescens Psilocybe aztecorum Heim Psilocybe cyanescens Wakefield Psilocybe collybioides Singer and Smith Description of Maire's sterile to semi-sterile material from Algeria Description of fertile material referred to Hypholoma cyanescens by Malençon Psilocybe strictipes Singer & Smith Psilocybe baeocystis Singer and Smith soma rights re-served 1 since 27.10.2016 at http://www.en.psilosophy.info/ mycological investigations on teonanacatl the mexican hallucinogenic mushroom www.en.psilosophy.info/zzvhmwgkbubhbzcmcdakcuak Stirps Caerulescens Psilocybe aggericola Singer & Smith Psilocybe candidipes Singer & Smith Psilocybe zapotecorum Heim Stirps Caerulipes Psilocybe Muliercula Singer & Smith Psilocybe caerulipes (Peck) Sacc. Literature cited soma rights re-served 2 since 27.10.2016 at http://www.en.psilosophy.info/ mycological investigations on teonanacatl the mexican hallucinogenic mushroom www.en.psilosophy.info/zzvhmwgkbubhbzcmcdakcuak Part I. -

The Good, the Bad and the Tasty: the Many Roles of Mushrooms

available online at www.studiesinmycology.org STUDIES IN MYCOLOGY 85: 125–157. The good, the bad and the tasty: The many roles of mushrooms K.M.J. de Mattos-Shipley1,2, K.L. Ford1, F. Alberti1,3, A.M. Banks1,4, A.M. Bailey1, and G.D. Foster1* 1School of Biological Sciences, Life Sciences Building, University of Bristol, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol, BS8 1TQ, UK; 2School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Cantock's Close, Bristol, BS8 1TS, UK; 3School of Life Sciences and Department of Chemistry, University of Warwick, Gibbet Hill Road, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK; 4School of Biology, Devonshire Building, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK *Correspondence: G.D. Foster, [email protected] Abstract: Fungi are often inconspicuous in nature and this means it is all too easy to overlook their importance. Often referred to as the “Forgotten Kingdom”, fungi are key components of life on this planet. The phylum Basidiomycota, considered to contain the most complex and evolutionarily advanced members of this Kingdom, includes some of the most iconic fungal species such as the gilled mushrooms, puffballs and bracket fungi. Basidiomycetes inhabit a wide range of ecological niches, carrying out vital ecosystem roles, particularly in carbon cycling and as symbiotic partners with a range of other organisms. Specifically in the context of human use, the basidiomycetes are a highly valuable food source and are increasingly medicinally important. In this review, seven main categories, or ‘roles’, for basidiomycetes have been suggested by the authors: as model species, edible species, toxic species, medicinal basidiomycetes, symbionts, decomposers and pathogens, and two species have been chosen as representatives of each category. -

Morphological Description and New Record of Panaeolus Acuminatus (Agaricales) in Brazil

Studies in Fungi 4(1): 135–141 (2019) www.studiesinfungi.org ISSN 2465-4973 Article Doi 10.5943/sif/4/1/16 Morphological description and new record of Panaeolus acuminatus (Agaricales) in Brazil Xavier MD1, Silva-Filho AGS2, Baseia IG3 and Wartchow F4 1 Curso de Graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Av. Senador Salgado Filho, 3000, Campus Universitário, 59072-970, Natal, RN, Brazil 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemática e Evolução, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Av. Senador Salgado Filho, 3000, Campus Universitário, 59072-970, Natal, RN, Brazil 3 Departamento de Botânica e Zoologia, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Av. Senador Salgado Filho, 3000, Campus Universitário, 59072-970, Natal, RN, Brazil 4 Departamento de Sistemática e Ecologia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Conj. Pres. Castelo Branco III, 58033- 455, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil Xavier MD, Silva-Filho AGS, Baseia IG, Wartchow F 2019 – Morphological description and new record of Panaeolus acuminatus (Agaricales) in Brazil. Studies in Fungi 4(1), 135–141, Doi 10.5943/sif/4/1/16 Abstract Panaeolus acuminatus is described and illustrated based on fresh specimens collected from Northeast Brazil. This is the second known report of this species for the country, since it was already reported in 1930 by Rick. The species is characterized by the acuminate, pileus with hygrophanous surface, basidiospores measuring 11.5–16 × 5.5–11 µm and slender, non-capitate cheilocystidia. A full description accompanies photographs, line drawings and taxonomic discussion. Key words – Agaricomycotina – Basidiomycota – biodiversity – dark-spored – Panaeoloideae – Rick Introduction Species of Panaeolus (Fr.) Quél. -

Baeocystin in Psilocybe, Conocybe and Panaeolus

Baeocystin in Psilocybe, Conocybe and Panaeolus DAVIDB. REPKE* P.O. Box 899, Los Altos, California 94022 and DALE THOMASLESLIE 104 Whitney Avenue, Los Gatos, California 95030 and GAST6N GUZMAN Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biologicas, l.P.N. Apartado Postal 26-378, Mexico 4. D.F. ABSTRACT.--Sixty collections of ten species referred to three families of the Agaricales have been analyzed for the presence of baeocystin by thin-layer chro- matography. Baeocystin was detected in collections of Peilocy be, Conocy be, and Panaeolus from the U.S.A., Canada, Mexico, and Peru. Laboratory cultivated fruit- bodies of Psilocybe cubensis, P. sernilanceata, and P. cyanescens were also studied. Intra-species variation in the presence and decay rate of baeocystin, psilocybin, and psilocin are discussed in terms of age and storage factors. In addition, evidence is presented to support the presence of 4-hydroxytryptamine in collections of P. baeo- cystis and P. cyanescens. The possible significance of baeocystin and 4·hydroxy- tryptamine in the biosynthesis of psilocybin in these organisms is discussed. A recent report (1) described the isolation of baeocystin [4-phosphoryloxy-3- (2-methylaminoethyl)indole] from collections of Psilocy be semilanceata (Fr.) Kummer. Previously, baeocystin had been detected only in Psilocybe baeo- cystis Singer and Smith (2, 3). This report now describes some further obser- vations regarding the occurrence of baeocystin in species referred to three families of Agaricales. Stein, Closs, and Gabel (4) isolated a compound from an agaric that they described as Panaeolus venenosus Murr., a species which is now considered synonomous with Panaeolus subbaIteatus (Berk. and Br.) Sacco (5, 6). -

Toxic Fungi of Western North America

Toxic Fungi of Western North America by Thomas J. Duffy, MD Published by MykoWeb (www.mykoweb.com) March, 2008 (Web) August, 2008 (PDF) 2 Toxic Fungi of Western North America Copyright © 2008 by Thomas J. Duffy & Michael G. Wood Toxic Fungi of Western North America 3 Contents Introductory Material ........................................................................................... 7 Dedication ............................................................................................................... 7 Preface .................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 7 An Introduction to Mushrooms & Mushroom Poisoning .............................. 9 Introduction and collection of specimens .............................................................. 9 General overview of mushroom poisonings ......................................................... 10 Ecology and general anatomy of fungi ................................................................ 11 Description and habitat of Amanita phalloides and Amanita ocreata .............. 14 History of Amanita ocreata and Amanita phalloides in the West ..................... 18 The classical history of Amanita phalloides and related species ....................... 20 Mushroom poisoning case registry ...................................................................... 21 “Look-Alike” mushrooms ..................................................................................... -

Checklist of the Argentine Agaricales 2. Coprinaceae and Strophariaceae

Checklist of the Argentine Agaricales 2. Coprinaceae and Strophariaceae 1 2* N. NIVEIRO & E. ALBERTÓ 1Instituto de Botánica del Nordeste (UNNE-CONICET). Sargento Cabral 2131, CC 209 Corrientes Capital, CP 3400, Argentina 2Instituto de Investigaciones Biotecnológicas (UNSAM-CONICET) Intendente Marino Km 8.200, Chascomús, Buenos Aires, CP 7130, Argentina *CORRESPONDENCE TO: [email protected] ABSTRACT—A checklist of species belonging to the families Coprinaceae and Strophariaceae was made for Argentina. The list includes all species published till year 2011. Twenty-one genera and 251 species were recorded, 121 species from the family Coprinaceae and 130 from Strophariaceae. KEY WORDS—Agaricomycetes, Coprinus, Psathyrella, Psilocybe, Stropharia Introduction This is the second checklist of the Argentine Agaricales. Previous one considered the families Amanitaceae, Pluteaceae and Hygrophoraceae (Niveiro & Albertó, 2012). Argentina is located in southern South America, between 21° and 55° S and 53° and 73° W, covering 3.7 million of km². Due to the large size of the country, Argentina has a wide variety of climates (Niveiro & Albertó, 2012). The incidence of moist winds coming from the oceans, the Atlantic in the north and the Pacific in the south, together with different soil types, make possible the existence of many types of vegetation adapted to different climatic conditions (Brown et al., 2006). Mycologists who studied the Agaricales from Argentina during the last century were reviewed by Niveiro & Albertó (2012). It is considered that the knowledge of the group is still incomplete, since many geographic areas in Argentina have not been studied as yet. The checklist provided here establishes a baseline of knowledge about the diversity of species described from Coprinaceae and Strophariaceae families in Argentina, and serves as a resource for future studies of mushroom biodiversity.