Freedom and Restraint in William Wycherley's Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Dryden and the Late 17Th Century Dramatic Experience Lecture 16 (C) by Asher Ashkar Gohar 1 Credit Hr

JOHN DRYDEN AND THE LATE 17TH CENTURY DRAMATIC EXPERIENCE LECTURE 16 (C) BY ASHER ASHKAR GOHAR 1 CREDIT HR. JOHN DRYDEN (1631 – 1700) HIS LIFE: John Dryden was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who was made England's first Poet Laureate in 1668. He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the “Age of Dryden”. The son of a country gentleman, Dryden grew up in the country. When he was 11 years old the Civil War broke out. Both his father’s and mother’s families sided with Parliament against the king, but Dryden’s own sympathies in his youth are unknown. About 1644 Dryden was admitted to Westminster School, where he received a predominantly classical education under the celebrated Richard Busby. His easy and lifelong familiarity with classical literature begun at Westminster later resulted in idiomatic English translations. In 1650 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. degree in 1654. What Dryden did between leaving the university in 1654 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 is not known with certainty. In 1659 his contribution to a memorial volume for Oliver Cromwell marked him as a poet worth watching. His “heroic stanzas” were mature, considered, sonorous, and sprinkled with those classical and scientific allusions that characterized his later verse. This kind of public poetry was always one of the things Dryden did best. On December 1, 1663, he married Elizabeth Howard, the youngest daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st earl of Berkshire. -

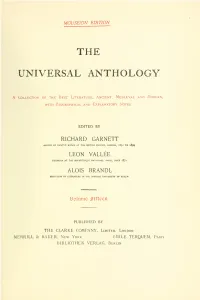

The Universal Anthology

MOUSEION EDITION THE UNIVERSAL ANTHOLOGY A Collection of the Best Literature, Ancient, Medieval and Modern, WITH Biographical and Explanatory Notes EDITED BY RICHARD GARNETT KEEPER OF PRINTED BOOKS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, 185I TO 1899 LEON VALLEE LIBRARIAN AT THE BIBLIOTHEQJJE NATIONALE, PARIS, SINCE I87I ALOIS BRANDL PKOFESSOR OF LITERATURE IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OP BERLIN IDoluine ififteen PUBLISHED BY THE CLARKE COMPANY, Limited, London MERRILL & BAKER. New York EMILE TERQUEM. Paris BIBLIOTHEK VERLAG, Berlin Entered at Stationers' Hall London, 1899 Droits de reproduction et da traduction reserve Paris, 1899 Alle rechte, insbesondere das der Ubersetzung, vorbehalten Berlin, 1899 Proprieta Letieraria, Riservate tutti i divitti Rome, 1899 Copyright 1899 by Richard Garnett IMMORALITY OF THE ENGLISH STAGE. 347 Young Fashion — Hell and Furies, is this to be borne ? Lory — Faith, sir, I cou'd almost have given him a knock o' th' pate myself. A Shoet View of the IMMORALITY AND PROFANENESS OF THE ENG- LISH STAGE. By JEREMY COLLIER. [Jeremy Collier, reformer, was bom in Cambridgeshire, England, in 1650. He was educated at Cambridge, became a clergyman, and was a " nonjuror" after the Revolution ; not only refusing the oath, but twice imprisoned, once for a pamphlet denying that James had abdicated, and once for treasonable corre- spondence. In 1696 he was outlawed for absolving on the scaffold two conspira- tors hanged for attempting William's life ; and though he returned later and lived unmolested in London, the sentence was never rescinded. Besides polemics and moral essays, he wrote a cyclopedia and an " Ecclesiastical IILstory of Great Britain," and translated Moreri's Dictionary. -

A Celebration of the Contributions of Dr. Mortimer J. Adler

A Celebration of the Contributions of Dr. Mortimer J. Adler August 19-21,1994 Aspen, Colorado Contents (interactive) Mortimer J. Adler: Philosopher at Midday- Jeffrey D. Wallin...................51 MJA, POLITICS: Summary - John Van Doren............................................76 Mortimer Adler: The Political Writings - John Van Doren........................79 Remarks – Mortimer J. Adler.......................................................................93 From the Editor’s Desk - Sydney Hyman...................................................95 Mortimer Adler and The Aspen Institute - Sidney Hyman........................99 Authors........................................................................................................118 51 Mortimer J. Adler: Philosopher at Midday Jeffrey D. Wallin ortimer J. Adler has made an unusual number of difficult M ideas accessible to “everybody.” Perhaps that is why he has been so uncharitably dismissed as a “popular” philosopher by his critics, a good number of whom come from that narrow breed of specialists once dismissed by Nietzsche as equipped at best to study the lives of a single species of insect, say, the leech, or that being too broad, perhaps only the leech’s brain. Adler is not a spe- cialist. He speaks to broad issues, issues of importance to all of us as men and women. Even more surprising, he speaks without jar- gon, evasion or irony. Unlike the owl of Minerva, which is said to begin its flight at dusk, this is one philosopher who learns and teaches in direct sunlight. Among the most important topics Adler has shed light upon are liberal education, democracy and human nature. Adler favors all of them, by the way. And nothing could further distance him from the strongest trends in American education. * * * In early May 1994 The New York Times carried a story about a controversy raging in Lake County, Florida. -

FRENCH INFLUENCES on ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE a Thesis

FRENCH INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of A the requirements for the Degree 2oK A A Master of Arts * In Drama by Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California Spring 2016 Copyright by Anne Melissa Potter 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read French Influences on English Restoration Theatre by Anne Melissa Potter, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts: Drama at San Francisco State University. Bruce Avery, Ph.D. < —•— Professor of Drama "'"-J FRENCH INFLUENCES ON RESTORATION THEATRE Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California 2016 This project will examine a small group of Restoration plays based on French sources. It will examine how and why the English plays differ from their French sources. This project will pay special attention to the role that women played in the development of the Restoration theatre both as playwrights and actresses. It will also examine to what extent French influences were instrumental in how women develop English drama. I certify that the abstract rrect representation of the content of this thesis PREFACE In this thesis all of the translations are my own and are located in the footnote preceding the reference. I have cited plays in the way that is most helpful as regards each play. In plays for which I have act, scene and line numbers I have cited them, using that information. For example: I.ii.241-244. -

Aphra Behn the Author Aphra Behn (1640-1689) Was One of the First Successful Female Writers in English History

Aphra Behn The Author Aphra Behn (1640-1689) was one of the first successful female writers in English history. She was born to Bartholomew Johnson and Elizabeth. Her most popular works included The Rover , Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister , and Oroonoko . Aphra Johnson married Johan Behn, who was a merchant of German or Dutch extraction. Little conclusive information is known about their marriage, but it did not last for more than a few years. Some scholars believe that the marriage never existed and Behn made it up purely to gain the status of a widow, which would have been much more beneficial for what she was trying to achieve. She was reportedly bisexual, and held a larger attraction to women than to men, a trait that, coupled with her writings and references of this nature, would eventually make her popular in the writing and artistic communities of the present day. Aphra Behn was also said to have been a spy for Charles II. She was given the code name Astrea under which she published many of her writings. Aphra Behn is known for being one of the first Englishwomen to earn a livelihood by authorship and is also credited with influencing future female writers and the development of the English novel toward realism. Attributing her success to her "ability to write like a man," she competed professionally with the prominent "wits" of Restoration England, including George Etherege, William Wycherley, John Dryden, and William Congreve. Similar to the literary endeavors of her male contemporaries, Behn's writings catered to the libertine tastes of King Charles II and his supporters, and occasionally excelled as humorous satires recording the A Playgoer’s Guide political and social events of the era. -

I the POLITICS of DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS

THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 by Loring Pfeiffer B. A., Swarthmore College, 2002 M. A., University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Loring Pfeiffer It was defended on May 1, 2015 and approved by Kristina Straub, Professor, English, Carnegie Mellon University John Twyning, Professor, English, and Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies, Courtney Weikle-Mills, Associate Professor, English Dissertation Advisor: Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, English ii Copyright © by Loring Pfeiffer 2015 iii THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 Loring Pfeiffer, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 The Politics of Desire argues that late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women playwrights make key interventions into period politics through comedic representations of sexualized female characters. During the Restoration and the early eighteenth century in England, partisan goings-on were repeatedly refracted through the prism of female sexuality. Charles II asserted his right to the throne by hanging portraits of his courtesans at Whitehall, while Whigs avoided blame for the volatility of the early eighteenth-century stock market by foisting fault for financial instability onto female gamblers. The discourses of sexuality and politics were imbricated in the texts of this period; however, scholars have not fully appreciated how female dramatists’ treatment of desiring female characters reflects their partisan investments. -

Masaryk University Unruly Women: Gender Reflection

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE UNRULY WOMEN: GENDER REFLECTION IN SHAKESPEAREAN FILM Bachelor Thesis BRNO 2012 Supervisor: Author: Ing. Mgr. Věra Eliášová, Ph.D. Kateřina Platzerová Prohlášení: “Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných literárních pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro student Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy university a se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů.” Declaration: I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the sources listed in the bibliography. ………………………. Brno 18.4. 2012 Kateřina Platzerová 1 Acknowledgment First of all I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Ing. Mgr. Věra Eliášová Ph.D. for her support and time. I am grateful for her helpful suggestions and valuable comments. I would also like to thank my family and friends who supported me through the years of my studies. 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 5 1. Gender, Film and Shakespeare .................................................................................. 7 1.1. Silent Era .................................................................................................... 9 1.1.1. Before the First World War ........................................................ -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

English and American Studies in Spain: New Developments and Trends

English and American Studies in Spain: New Developments and Trends Editors: Alberto Lázaro Lafuente María Dolores Porto Requejo HUMANIDADES 47 OBRAS COLECTIVAS UAH English and American Studies in Spain: New Developments and Trends OBRAS COLECTIVAS HUMANIDADES 47 English and American Studies in Spain: New Developments and Trends Editors: Alberto Lázaro Lafuente María Dolores Porto Requejo © Editors: Alberto Lázaro Lafuente & María Dolores Porto Requejo. © Texts: the authors. © Images: as stated in each case. If not stated explicitly, the responsibility lies with the author of the essay. © This edition: Universidad de Alcalá • Servicio de Publicaciones, 2015 Plaza de San Diego, s/n • 28801, Alcalá de Henares (España). Web: www.uah.es Cover image: Jonathan Sell, 38th AEDEAN Conference Organising Committee Total or partial reproduction of this book is not permitted, nor its informatic treatment, or the transmission of any form or by any means, either electronic, mechanic, photocopy or other methods, without the prior written permission of the owners of the copyright. I.S.B.N.: 978-84-16599-11-0 Contents Preface .................................................................................................................. 9 PART I: KEYNOTES CLARA CALVO, Universidad de Murcia Shakespeare in Khaki...................................................................................... 12 ROGER D. SELL, Åbo Akademi University Pinter, Herbert, Dickens: Post-postmodern Communicational Studies and the Humanities ..................................................................................................... -

The English Restoration: Theatre Returns from Exile

The English Restoration: Theatre Returns from Exile In 1649, Oliver Cromwell and his followers, the religiously conservative Puritans, beheaded King Charles I, and for over eleven years England was ruled by Cromwell. In 1658, after Cromwell died, the royal family was asked to return to England from France, where they had been living in exile. In 1660, Charles II became king and the monarchy was “restored” to power, which is why this period of time is called the Restoration Period. When the English royalty and nobility returned to England, they brought with them a taste for the French theatrical practices that they had enjoyed as audience members in France. This pleased the English because the Puritans had closed all theatres in 1642. With the Restoration came a resurgence of theatrical activity. As you may recall, English theatre during the Renaissance had not been like the theatre popular in Italy and France. English playwrights and producers did not use painted perspective scenery, for example, but had continued to use very few furnishings to suggest a location for the action. After the Restoration, the Elizabethan practices and the Italian and French stage arrangements were merged to form a unique, new kind of theatre. This combination of styles affected the form of the plays, the organization of the theatre companies, the theatre buildings themselves, and the use of scenery on stage. The Restoration was not a period of great tragic plays. Most of the Restoration tragedies were heroic tragedies about extraordinary heroes who did extraordinary deeds. While entertaining, these plays were usually too far removed from reality to have much credibility. -

English Literature 1590 – 1798

UGC MHRD ePGPathshala Subject: English Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee; University of Hyderabad Paper 02: English Literature 1590 – 1798 Paper Coordinator: Dr. Anna Kurian; University of Hyderabad Module No 31: William Wycherley: The Country Wife Content writer: Ms.Maria RajanThaliath; St. Claret College; Bangalore Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee; University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Dr. Anna Kurian; University of Hyderabad William Wycherley’s The Country Wife Introduction This lesson deals with one of the most famous examples of Restoration theatre: William Wycherley’s The Country Wife, which gained a reputation in its time for being both bawdy and witty. We will begin with an introduction to the dramatist and the form and then proceed to a discussion of the play and its elements and conclude with a survey of the criticism it has garnered over the years. Section One: William Wycherley and the Comedy of Manners William Wycherley (b.1640- d.1716) is considered one of the major Restoration playwrights. He wrote at a time when the monarchy in England had just been re-established with the crowning of Charles II in 1660. The newly crowned king effected a cultural restoration by reopening the theatres which had been shut since 1642. There was a proliferation of theatres and theatre-goers. A main reason for the last was the introduction of women actors. Puritan solemnity was replaced with general levity, a characteristic of the Caroline court. Restoration Comedy exemplifies an aristocratic albeit chauvinistic lifestyle of relentless sexual intrigue and conquest. The Comedy of Manners in particular, satirizes the pretentious morality and wit of the upper classes. -

"Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2011 "Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World Jarred Wiehe Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wiehe, Jarred, ""Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 148. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/148 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/playyourfanexploOOwieh "Play your fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through The Country Wife, The Man of Mode, The Rover, and The Way of the World By Jarred Wiehe A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program For Honors in the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In English Literature, College of Letters and Sciences, Columbus State University x Thesis Advisor Date % /Wn l ^ Committee Member Date Rsdftn / ^'7 CSU Honors Program Director C^&rihp A Xjjs,/y s z.-< r Date <F/^y<Y'£&/ Wiehe 1 'Play your fan': Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage through The Country Wife, The Man ofMode, The Rover, and The Way of the World The full irony and wit of Restoration comedies relies not only on what characters communicate to each other, but also on what they communicate to the audience, both verbally and physically.