Accessibility of Legislation in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Addition and Modification of Reliefs) (Scotland) Order 2015 No

Draft Legislation: This is a draft item of legislation. This draft has since been made as a Scottish Statutory Instrument: The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Addition and Modification of Reliefs) (Scotland) Order 2015 No. 93 Draft Order laid before the Scottish Parliament under section 68(2) of the Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Scotland) Act 2013, for approval by resolution of the Scottish Parliament. DRAFT SCOTTISH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2015 No. LAND AND BUILDINGS TRANSACTION TAX The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Addition and Modification of Reliefs) (Scotland) Order 2015 Made - - - - 2015 Coming into force - - 1st April 2015 The Scottish Ministers make the following Order in exercise of the powers conferred by section 27(3) of the Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Scotland) Act 2013(1). In accordance with section 68(2) of that Act a draft of this Order has been laid before and approved by resolution of the Scottish Parliament. Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Addition and Modification of Reliefs) (Scotland) Order 2015. (2) This Order comes into force on 1st April 2015. Addition and modification of reliefs 2.—(1) The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Scotland) Act 2013 is amended as follows. (2) In section 27(1) (reliefs)— (a) after “schedule 13 (charities relief)”, insert— “schedule 13A (friendly societies relief), schedule 13B (building societies relief),”; (b) after “schedule 16 (public bodies relief),” insert— “schedule 16A (visiting forces and international military headquarters reliefs), schedule 16B (relief for property accepted in satisfaction of tax), schedule 16C (lighthouses relief).”. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N HANSARD Douglas, Tuesday, 17th July 2018 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website: www.tynwald.org.im/business/hansard Supplementary material provided subsequent to a sitting is also published to the website as a Hansard Appendix. Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted on application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. Volume 135, No. 14 ISSN 1742-2256 Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. © High Court of Tynwald, 2018 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 17th JULY 2018 Present: The Deputy President of Tynwald (Hon. J P Watterson) In the Council: The Lord Bishop of Sodor and Man (The Rt Rev. P A Eagles), The Attorney General (Mr J L M Quinn QC), Miss T M August-Hanson, Mr D C Cretney, Mr T M Crookall, Mr R W Henderson, Mrs M M Hendy, Mrs K A Lord-Brennan, Mrs J P Poole-Wilson and Mrs K Sharpe with Mr J D C King, Deputy Clerk of Tynwald. In the Keys: The Deputy Speaker (Mr C R Robertshaw) (Douglas East); The Chief Minister (Hon. -

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, 'The Failure of Criminal Law To

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, ‘The Failure of Criminal Law to Control the Use of Off Balance Sheet Finance During the Banking Crisis’ (2015) 36 The Company Lawyer, Issue 4, 99, reproduced with permission of Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd. This extract is taken from the author’s original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/document?&srguid=i0ad8289e0000014eca3cbb3f02 6cd4c4&docguid=I83C7BE20C70F11E48380F725F1B325FB&hitguid=I83C7BE20C70F11 E48380F725F1B325FB&rank=1&spos=1&epos=1&td=25&crumb- action=append&context=6&resolvein=true THE FAILURE OF CRIMINAL LAW TO CONTROL THE USE OF OFF BALANCE SHEET FINANCE DURING THE BANKING CRISIS Dr Stephen Copp & Alison Cronin1 30th May 2014 Introduction A fundamental flaw at the heart of the corporate structure is the scope for fraud based on the provision of misinformation to investors, actual or potential. The scope for fraud arises because the separation of ownership and control in the company facilitates asymmetric information2 in two key circumstances: when a company seeks to raise capital from outside investors and when a company provides information to its owners for stewardship purposes.3 Corporate misinformation, such as the use of off balance sheet finance (OBSF), can distort the allocation of investment funding so that money gets attracted into less well performing enterprises (which may be highly geared and more risky, enhancing the risk of multiple failures). Insofar as it creates a market for lemons it risks damaging confidence in the stock markets themselves since the essence of a market for lemons is that bad drives out good from the market, since sellers of the good have less incentive to sell than sellers of the bad.4 The neo-classical model of perfect competition assumes that there will be perfect information. -

Irish Constitutional Law

1 ERASMUS SUMMER SCHOOL MADRID 2011 IRISH CONSTITUTIONAL LAW Martin Kearns Barrister at Law Historical Introduction The Treaty of December 6, 1921 was the foundation stone of an independent Ireland under the terms of which the Irish Free State was granted the status of a self-governing dominion, like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. Although the Constitution of the Ireland ushered in virtually total independence in the eyes of many it had been imposed by Britain through the Anglo Irish Treaty. 1 The Irish Constitution of 1922 was the first new Constitution following independence from Britain but by 1936 it had been purged of controversial symbols and external associations by the Fianna Faíl Government which had come to power in 1932.2 The Constitution of Ireland replaced the Constitution of the Irish Free State which had been in effect since the independence of the Free State from the United Kingdom on 6 December 1922. The motivation of the new Constitution was mainly to put an Irish stamp on the Constitution of the Free State whose institutions Fianna Faíl had boycotted up to 1926. 1 Signed in London on 6 December 1921. 2 e.g. under Article 17 every member of the Oireachtas had to take an oath of allegiance, swearing true faith and allegiance to the Constitution and fidelity to the Monarch; the representative of the King known as the Governor General etc. 2 Bunreacht na hÉireann an overview The official text of the constitution consists of a Preamble and fifty articles arranged under sixteen headings. Its overall length is approximately 16,000 words. -

Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill

Number: WG34368 Welsh Government Consultation Document Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill Date of issue : 20 March 2018 Action required : Responses by 12 June 2018 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown Copyright Overview This document sets out the Welsh Government’s proposals to improve the accessibility and statutory interpretation of Welsh law, and seeks views on the Draft Legislation (Wales) Bill. How to respond Please send your written response to the address below or by email to the address provided. Further information Large print, Braille and alternative language and related versions of this document are available on documents request. Contact details For further information: Office of the Legislative Counsel Welsh Government Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NQ email: [email protected] telephone: 0300 025 0375 Data protection The Welsh Government will be data controller for any personal data you provide as part of your response to the consultation. Welsh Ministers have statutory powers they will rely on to process this personal data which will enable them to make informed decisions about how they exercise their public functions. Any response you send us will be seen in full by Welsh Government staff dealing with the issues which this consultation is about or planning future consultations. In order to show that the consultation was carried out properly, the Welsh Government intends to publish a summary of the responses to this document. We may also publish responses in full. Normally, the name and address (or part of the address) of the person or 1 organisation who sent the response are published with the response. -

Cronk Keeill Abban (Old Tynwald Site)

Access Guide to Cronk Keeill Abban (Old Tynwald Site) Manx National Heritage has the guardianship of many ancient monuments in the landscape. A number of these sites are publicly accessible. Please note in most circumstances the land is not in the ownership of Manx National Heritage and visits are made at your own risk. We recognise that visiting the Island’s ancient monuments in the countryside can present difficulties for people with disabilities. We have prepared an access guide for visiting Cronk Keeill Abban (Old Tynwald Site) to help you plan your visit. This access guide does not contain personal opinions as to suitability for those with access needs, but aims to accurately describe the environment at the site. Introduction Cronk Keeill Abban in Braddan is the site of an Early Christian Keeill and was a former Viking assembly site. It is one of four historically recorded assembly sites in the Isle of Man – the others being Tynwald Hill, Castle Rushen and another in Kirk Michael. The earliest written reference to this being a Tynwald site dates from 1429. At this Tynwald sitting the record states that ‘trial by combat’ was abolished. The word Tynwald comes from the Norse thingvollr, meaning place of the parliament or assembly field. The annual meeting held at Tynwald Hill in St John’s would have been the “all-Island” meeting – smaller local groups would have met elsewhere throughout the year. The exact location of the assembly site is not clear, and the present circular dry stone enclosure was constructed in 1929 to commemorate its existence. -

Government of Ireland Act, 1920. 10 & 11 Geo

?714 Government of Ireland Act, 1920. 10 & 11 GEo. 5. CH. 67.] To be returned to HMSO PC12C1 for Controller's Library Run No. E.1. Bin No. 0-5 01 Box No. Year. RANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. A.D. 1920. IUD - ESTABLISHMENT OF PARLIAMENTS FOR SOUTHERN IRELAND. AND NORTHERN IRELAND AND A COUNCIL OF IRELAND. Section. 1. Establishment of Parliaments of Southern and Northern Ireland. 2. Constitution of Council of Ireland. POWER TO ESTABLISH A PARLIAMENT FOR THE WHOLE OF IRELAND. Power to establish a Parliament for the whole of Ireland. LEGISLATIVE POWERS. 4. ,,.Legislative powers of Irish Parliaments. 5. Prohibition of -laws interfering with religious equality, taking property without compensation, &c. '6. Conflict of laws. 7. Powers of Council of Ireland to make orders respecting private Bill legislation for whole of Ireland. EXECUTIVE AUTHORITY. S. Executive powers. '.9. Reserved matters. 10. Powers of Council of Ireland. PROVISIONS AS TO PARLIAMENTS OF SOUTHERN AND NORTHERN IRELAND. 11. Summoning, &c., of Parliaments. 12. Royal assent to Bills. 13. Constitution of Senates. 14. Constitution of the Parliaments. 15. Application of election laws. a i [CH. 67.1 Government of Ireland Act, 1920, [10 & 11 CEo. A.D. 1920. Section. 16. Money Bills. 17. Disagreement between two Houses of Parliament of Southern Ireland or Parliament of Northern Ireland. LS. Privileges, qualifications, &c. of members of the Parlia- ments. IRISH REPRESENTATION IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS. ,19. Representation of Ireland in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. FINANCIAL PROVISIONS. 20. Establishment of Southern and Northern Irish Exchequers. 21. Powers of taxation. 22. -

Supreme Court Visit to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Welcoming the Supreme Court to NUI Galway

Supreme Court Visit to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Welcoming the Supreme Court to NUI Galway 4-6 March, 2019 Table of Contents Welcome from the Head of School . 2 Te School of Law at NUI Galway . 4 Te Supreme Court of Ireland . 6 Te Judges of the Supreme Court . 8 2 Welcome from the Head of School We are greatly honoured to host the historic sittings of the Irish Supreme Court at NUI Galway this spring. Tis is the frst time that the Supreme Court will sit outside of a courthouse since the Four Courts reopened in 1932, the frst time the court sits in Galway, and only its third time to sit outside of Dublin. To mark the importance of this occasion, we are running a series of events on campus for the public and for our students. I would like to thank the Chief Justice and members of the Supreme Court for participating in these events and for giving their time so generously. Dr Charles O’Mahony, Head of School, NUI Galway We are particularly grateful for the Supreme Court’s willingness to engage with our students. As one of Ireland’s leading Law Schools, our key focus is on the development of both critical thinking and adaptability in our future legal professionals. Tis includes the ability to engage in depth with the new legal challenges arising from social change, and to analyse and apply the law to developing legal problems. Te Supreme Court’s participation in student seminars on a wide range of current legal issues is not only deeply exciting for our students, but ofers them an excellent opportunity to appreciate at frst hand the importance of rigorous legal analysis, and the balance between 3 necessary judicial creativity and maintaining the rule of law. -

History and Chronology

34 HISTORY AND CHRONOLOGY chewan. Aug. 1, H. M. Airship of the Transatlantic Airways. Nov. R-100 arrived at Montreal, being 29, Royal Commission on Do the first transatlantic lighter-than- minion-Provincial Relations opened air craft to reach Canada. Oct. 1, sittings at Winnipeg. Imperial Conference at London. 1938. Mar. 4, Unanimous judgments of the 1931. June 1, Seventh Dominion Census Supreme Court of Canada on the (population 10,376,786). June 30, Alberta constitutional references The Statute of Westminster exempt made in favour of the Dominion ing the Dominion and the provinces Government. (See 1941 Year from the operation of the Colonial Book, p. 19, for further references Laws Validity Act and the Mer to this subject.) Mar. 13, Seizure chant Shipping Act approved by of Austria by Germany. June 9, the House of Commons. Sept. 21, Provincial general election in Sas United Kingdom suspended specie katchewan; Liberal Government payments, following which Canada of Hon. W. J. Patterson returned to restricted the export of gold. Nov. power. Sept. 12, Herr Hitler's 21, Abnormal Importations Act, speech at Nuremberg followed by extending preference to Empire pro clashes on the Czechoslovak border, ducts, assented to in the United developed into an international Kingdom. Dec. 12, Statute of West crisis. Sept. 15, Meeting of Mr. minster establishing complete legis Chamberlain and Herr Hitler at lative equality of the Parliament of Berchtesgaden. Sept. 22-23, Meeting Canada with that of the United of Mr. Chamberlain and Herr Kingdom became effective. Hitler at Godesberg. Sept. 28, Mobilization of British fleet. Sept. 1932. -

Democracy in the Age of Pandemic – Fair Vote UK Report June 2020

Democracy in the Age of Pandemic How to Safeguard Elections & Ensure Government Continuity APPENDICES fairvote.uk Published June 2020 Appendix 1 - 86 1 Written Evidence, Responses to Online Questionnaire During the preparation of this report, Fair Vote UK conducted a call for written evidence through an online questionnaire. The questionnaire was open to all members of the public. This document contains the unedited responses from that survey. The names and organisations for each entry have been included in the interest of transparency. The text of the questionnaire is found below. It indicates which question each response corresponds to. Name Organisation (if applicable) Question 1: What weaknesses in democratic processes has Covid-19 highlighted? Question 2: Are you aware of any good articles/publications/studies on this subject? Or of any countries/regions that have put in place mediating practices that insulate it from the social distancing effects of Covid-19? Question 3: Do you have any ideas on how to address democratic shortcomings exposed by the impact of Covid-19? Appendix 1 - 86 2 Appendix 1 Name S. Holledge Organisation Question 1 Techno-phobia? Question 2 Estonia's e-society Question 3 Use technology and don't be frightened by it 2 Appendix 1 - 86 3 Appendix 2 Name S. Page Organisation Yes for EU (Scotland) Question 1 The Westminster Parliament is not fit for purpose Question 2 Scottish Parliament Question 3 Use the internet and electronic voting 3 Appendix 1 - 86 4 Appendix 3 Name J. Sanders Organisation emergency legislation without scrutiny removing civil liberties railroading powers through for example changes to mental health act that impact on individual rights (A) Question 1 I live in Wales, and commend Mark Drakeford for his quick response to the crisis by enabling the Assembly to continue to meet and debate online Question 2 no, not until you asked. -

Arrangement of Sections

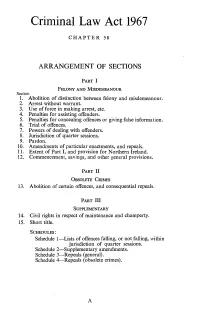

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

Butterworths UK Statutes Copyright 2003, Butterworths Tolley UK a Division of Reed Elsevier, Inc

Butterworths UK Statutes Copyright 2003, Butterworths Tolley UK a division of Reed Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. *** THIS DOCUMENT IS CURRENT THROUGH 19 FEBRUARY, 2003 *** FORGERY AND COUNTERFEITING ACT 1981 1981 CHAPTER 45 Royal Assent [27 July 1981] Forgery and Counterfeiting Act 1981, Ch. 45, Enactment Clause (Eng.) Enactment Clause BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- Long Title An Act to make fresh provision for England and Wales and Northern Ireland with respect to forgery and kindred offences; to make fresh provision for Great Britain and Northern Ireland with respect to the counterfeiting of notes and coins and kindred offences; to amend the penalties for offences under section 63 of the Post Office Act 1953; and for connected purposes PART I FORGERY AND KINDRED OFFENCES 1 The offence of forgery A person is guilty of forgery if he makes a false instrument, with the intention that he or another shall use it to induce somebody to accept it as genuine, and by reason of so accepting it to do or not to do some act to his own or any other person's prejudice. 2 The offence of copying a false instrument It is an offence for a person to make a copy of an instrument which is, and which he knows or believes to be, a false instrument, with the intention that he or another shall use it to induce somebody to accept it as a copy of a genuine instrument, and by reason of so accepting it to do or not to do some act to his own or any other person's prejudice.