Peter Temple's Truth and Truthfulness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Westonian Magazine in THIS ISSUE: BEHIND the NUMBERS Annual Report for 2016–2017

WINTER 2018 The Westonian Magazine IN THIS ISSUE: BEHIND THE NUMBERS Annual Report for 2016–2017 The [R]evolution of Science at Westtown FIG. 1 Mission-Based Science Meets the 21st Century The Westonian, a magazine for alumni, parents, and friends, is published by Westtown School. Its mission is “to capture the life of the school, to celebrate the impact that our students, faculty, and alumni have on our world, and to serve as a forum for connection, exploration, and conversation.” We publish issues in Winter and Summer. We welcome letters to the editor. You may send them to our home address or to [email protected]. HEAD OF SCHOOL Jeff DeVuono James Perkins ’56 Victoria H. Jueds Jacob Dresden ’62, Keith Reeves ’84 Co-Associate Clerk Anne Roche CONNECT BOARD OF TRUSTEES Diana Evans ’95 Kevin Roose ’05 Amy Taylor Brooks ’88 Jonathan W. Evans ’73, Daryl Shore ’99 Martha Brown Clerk Michael Sicoli ’88 Bryans ’68 Susan Carney Fahey Danielle Toaltoan ’03 Beah Burger- Davis Henderson ’62 Charlotte Triefus facebook.com/westtownschool Lenehan ’02 Gary M. Holloway, Jr. Kristen Waterfield twitter.com/westtownschool Luis Castillo ’80 Sydney Howe-Barksdale Robert McLear Edward C. Winslow III ’64 vimeo.com/westtownschool Michelle B. Caughey ’71, Ann Hutton Brenda Perkins ’75, Maximillian Yeh ’87 instagram.com/westtownschool Co-Associate Clerk Jess Lord ’90 Recording Clerk WINTER 2018 The Westonian Magazine Editor Lynette Assarsson, Associate Director FEATURES of Communications Manager of The (R)evolution of Web Features Greg Cross, 16 Science at -

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

Book History in Australia Since 1950 Katherine Bode Preprint: Chapter 1

Book History in Australia since 1950 Katherine Bode Preprint: Chapter 1, Oxford History of the Novel in English: The Novel in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the South Pacific since 1950. Edited by Coral Howells, Paul Sharrad and Gerry Turcotte. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. Publication of Australian novels and discussion of this phenomenon have long been sites for the expression of wider tensions between national identity and overseas influence characteristic of postcolonial societies. Australian novel publishing since 1950 can be roughly divided into three periods, characterized by the specific, and changing, relationship between national and non-national influences. In the first, the 1950s and 1960s, British companies dominated the publication of Australian novels, and publishing decisions were predominantly made overseas. Yet a local industry also emerged, driven by often contradictory impulses of national sentiment, and demand for American-style pulp fiction. In the second period, the 1970s and 1980s, cultural nationalist policies and broad social changes supported the growth of a vibrant local publishing industry. At the same time, the significant economic and logistical challenges of local publishing led to closures and mergers, and—along with the increasing globalization of publishing—enabled the entry of large, multinational enterprises into the market. This latter trend, and the processes of globalization and deregulation, continued in the final period, since the 1990s. Nevertheless, these decades have also witnessed the ongoing development and consolidation of local publishing of Australian novels— including in new forms of e-publishing and self-publishing—as well as continued government and social support for this activity, and for Australian literature more broadly. -

High Wire Act: Peter Carey's My Life As a Fake Anthony

The Journal of the European Association for Studies of Australia, Vol.6 No.1, 2015 High Wire Act: Peter Carey’s My Life as a Fake Anthony J. Hassall Copyright © Anthony J. Hassall 2015. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Abstract: This essay examines how Carey displays the multiple fakeries of fiction in My Life as a Fake. It notes the multiple inter-textual references to the Ern Malley hoax and the gothic horror of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. It examines the three unreliable narrating voices, the uneven characterisation of Christopher Chubb, and the magic realism seeking to animate Bob McCorkle and his present/absent book My Life as a Fake. It argues that the dazzling display of meta-fictional complexity, much celebrated by reviewers, contributes to the book’s failure to create engaging characters and a credible narrative. Keywords: fiction; fakery; meta-fictional complexity; inter-textual reference; unreliable narration; engaging characters; credible narrative I Peter Carey’s My Life as a Fake (2003) is a typically risk-taking venture. Its spectacular exposure of the multiple fakeries involved in telling the stories of fictional characters is compelling, but it is less persuasive in rendering those fictional characters credible and sympathetic. The first of Carey’s books to be published by Random House, it did not emulate the spectacular success of True History of the Kelly Gang. Initially uncertain of how to respond, some reviewers devoted more space to re-telling the Ern Malley story than to the book itself, which understandably frustrated the author (“Carey’s take on snub?” 1). -

Reading Group Notes

TEXT PUBLISHING melbourne australia Reading Group Notes Truth Peter Temple PAPERBACK ISBN 978-1-921520-71-6 RRP AUS $32.95, NZ $37.00 HARDBACK ISBN 978-1-921520-91-4 RRP AUS $45.00, NZ $50.00 Fiction Praise for Truth colleagues scheme and jostle, he finds all the certainties ‘[Temple] is the man who has transfigured the crime of his life are crumbling. novel and made it the pretext for an art that repudiates Truth is a novel about a man, a family, a city. It is about genre.’ Peter Craven, Weekend Australian violence, murder, love, corruption, honour and deceit. ‘Truth succeeds as...one of the best pieces of modern And it is about truth. Australian fiction this decade, if not for many decades.’ Courier Mail Truth is a companion piece of sorts, to Temple’s The Broken Shore. The protagonist here is Detective ‘Truth is a novel of rare power and much of that potency Inspector Stephen Villani, friend and former colleague of lies in its silences. The blank spaces occupy almost as The Broken Shore’s hero Joe Cashin. much of its pages as the print. The dialogue conveys only that which is necessary, sometimes not even that. Set predominantly in Melbourne, the ongoing theme The bareness of the bones reveals the soul. Propelled is that there is something rotten in the state of Victoria, forward by the momentum of the story, we cling to and in Villani’s life. It begins with Villani driving between fragments of veracity from which it is engineered.’ two shocking cases, and ends in devastating bushfire. -

Dialogue 2019

Dialogue 2019 CAE Book Groups Catalogue CAE BOOK GROUPS 253 FLINDERS LANE, MELBOURNE CAE.EDU.AU / 03 9652 0611 Contents 4 5 3 Join or Start a Growing Up, Book Discussion Service. 527 Collins Street Introduction CAE Book Group Moving On Contact Us 11 Level 2, 253 Flinders Lane Exceptional Women Melbourne VIC 3000 17 P (03) 9652 0611 Artist, 23 E [email protected] Maker, Thinker Relationships W www.cae.edu.au 31 45 Keep informed about upcoming Step Back in Time Families literary events, book reviews, book and movie giveaways and lots more. Email [email protected] to receive regular 38 email updates. Grand VIsions Start your own group 62 See page 4 for more information about Surviving, starting a group. Prevailing Join an existing group 55 70 Some of our existing groups are looking Journeys Dark Deeds for new members. Please contact CAE Book Groups, and we will help you find 78 82 87 a group in your area. Index by Index by Index by Author Title Large Type 87 91 Index by Enrolment Form Box Number 3 Introduction Centre for Adult Education CAE is a leading provider of Adult and Community Education and Theme Icons has been providing lifelong learning opportunities to Victorians for 70 years. CAE has a strong focus on delivering nationally F Fiction Large Print recognised and accredited training as well as non accredited L Nonfiction short courses, and connects with the community through socially N Adapted Books inclusive practices that recognise diversity and creativity. Located S Short Stories Book Group Favourite in the heart of the arts and café area of Melbourne’s CBD, CAE µ offers a vibrant and supportive adult learning environment, flexible learning options, skills recognition, practical training and supervised work placements. -

Highlights London Book Fair 2018 Highlights

Highlights London Book Fair 2018 Highlights Welcome to our 2018 International Book Rights Highlights For more information please go to our website to browse our shelves and find out more about what we do and who we represent. Contents Gregory & Company titles Crime, Suspense, Thriller 1-15 Contemporary Fiction 16 Historical Fiction 17 Romantic Fiction 18 DHA Fiction Literary/Upmarket Fiction 20-28 Crime, Suspense, Thriller 29-33 Commercial Fiction 34-37 DHA Non-Fiction Business & Lifestyle 38-39 History, Philosophy, Politics 40-45 Nature & Travel 46-49 Centenary Celebrations 50 Upcoming Publications 51-52 Film & TV News 53-54 DHA Sub-agents 55 Agents US Rights: Veronique Baxter; Georgia Glover; Anthony Goff (AG); Andrew Gordon (AMG); Jane Gregory; Lizzy Kremer; Harriet Moore; Caroline Walsh Film & TV Rights: Clare Israel; Nicky Lund; Penelope Killick; Georgina Ruffhead Translation Rights: Alice Howe: [email protected] Direct: France; Germany; Netherlands Subagented: Italy Claire Morris: [email protected] Gregory & Company list, all territories Direct: Germany; Greece; Netherlands; Portugal; Scandinavia; Spain; Vietnam plus miscellaneous requests Subagented: Brazil; China; Croatia; Czech Republic; France; Hungary; Israel; Japan; Korea; Poland; Romania; Russia; Serbia; Slovenia; Taiwan; Thailand; Turkey Emily Randle: [email protected] Direct: Afrikaans; all Indian languages; Brazil; Portugal; Vietnam; Wales; plus miscellaneous requests Subagented: China; Bulgaria; Hungary, Indonesia; Japan; Korea; Russia, Serbia; Taiwan; Thailand; Ukraine Giulia Bernabè: [email protected] Direct: Arabic; Croatia; Estonia; Greece; Israel; Latvia; Lithuania; Scandinavia; Slovenia; Spain and Spanish in Latin America; Sub-agented: Czech Republic; Poland; Romania; Slovakia; Turkey Contact t: +44 (0)20 7434 5900 f: +44 (0)20 7437 1072 www.davidhigham.co.uk Gregory & Company Titles Snap Belinda Bauer Snap decisions can be fatal . -

Gregory & Company

GREGORY & COMPANY AUTHORS’ AGENTS 3, BARB MEWS, LONDON W6 7PA TELEPHONE: 020 7610 4676 FAX: 020 7610 4686 WEBSITE: www.gregoryandcompany.co.uk EMAIL: [email protected] Rights Enquiries: Jane Gregory - UK, US, Film & TV: [email protected] Claire Morris – Translation: [email protected] Translation Rights (Highlights) Frankfurt 2015 For further information about our authors and their backlists, do visit our website www.gregoryandcompany.co.uk BAUER, Belinda Belinda Bauer grew up in England and South Africa. She has worked as a journalist and screenwriter, and her script for THE LOCKER ROOM earned her the Carl Foreman/ Bafta Award for Young British Screenwriters. With her first novel BLACKLANDS, Belinda won the CWA Gold Dagger for Crime Novel of the Year in 2010. Her next two novels, DARKSIDE and FINDERS KEEPERS, were also highly acclaimed, and in 2012 she was shortlisted for the CWA Dagger in the Library Award for her entire body of work. This year her 2015 novel THE SHUT EYE is shortlisted for the CWA Goldsboro Gold Dagger. RUBBERNECKER won the 2014 Theakston’s Crime Novel of the Year Award, which Belinda was shortlisted for again this year with her novel THE FACTS OF LIFE AND DEATH. Belinda is currently working on her seventh novel. THE BEAUTIFUL DEAD TV crime reporter Eve Singer’s flagging career is revived by a spate of bizarre murders – each one in public and advertised like an exhibition. When the perpetrator contacts Eve to discuss her coverage of his crimes, she is suddenly on the inside of the biggest serial killer investigation of the decade. -

Fox Evil Free Ebook

FREEFOX EVIL EBOOK Minette Walters | 576 pages | 05 Jul 2012 | Pan MacMillan | 9781447207993 | English | London, United Kingdom Evil (TV series) - Wikipedia Sign up for our newsletters! Who is the man called Fox Evil? His 10 year-old son if the boy really is his Fox Evil and really is as old as ten thinks Evil is Fox's last name. Certainly the word fits his personality and his actions. From the beginning pages we want to know Fox's true identity; as the pages add up, Fox Evil want to know how he got to be as cruel and twisted as he is, and Fox Evil drives him. It is not until the very end of the book that we will learn Fox Evil answers, by which time Walters's sustained narrative tension will have stretched our nerves very thin indeed. Her relentlessly dark view is enough to make even a fan of the gothic and the noir long nostalgically for the innocence of a Miss Marple, or of an Inspector Wexford for Ruth Rendell, even writing as Barbara Vine, is not this dark. Shenstead Valley is in Dorset, so ideally located between wooded hills and the sea that its small collection of houses and cottages, clustered about Shenstead Manor, has become off-limits to all but the stubborn Fox Evil and the new rich. Most of the latter spend their weekdays in London, but a trouble-making few have chosen Shenstead for their retirement. The major available forms of recreation are the local hunt club, a little golf, and a lot of gossip the latter being of the lethal, not-so-idle variety. -

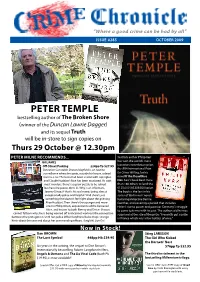

PETER Temple

“Where a good crime can be had by all” ISSUE #285 OCTOBER 2009 PEter TEmpLE bestselling author of The Broken Shore (winner of the Duncan Lawrie Dagger) and its sequel Truth will be in-store to sign copies on Thurs 29 October @ 12.30pm Peter MILne reCommends... Scottish author Philip Kerr Bill JAMES has won the world’s most Off-Street Parking 224pp Tp $27.95 lucrative crime fiction prize, Detective Constable Sharon Mayfield is on routine the RBA International Prize surveillance when she spots, outside his house, a dead for Crime Writing, for his man in a car. The locks had been sealed with superglue novel If the Dead Rise and Claude Huddart’s face has been mutilated. As with Not. Kerr’s book beat more most murders, there’s a jigsaw puzzle to be solved. than 160 others to land the But here the pieces don’t fit. Why is an informant, €125,000 (A$209,500) prize. Jeremy Dince, if that is his real name, being almost The book is the last in his exceptionally polite and helpful? And there’s just series of ‘Berlin noir’ novels something that doesn’t feel right about the grieving featuring detective Bernie Alice Huddart. Then there’s the younger and more Gunther, and covering a period that includes sinister Philip Otton, acquaintance of the bereaved Hitler’s rise to power and postwar Germany’s struggle Alice, and known to both Blenny and Dince. Sharon to come to terms with its past. The author said he was cannot fathom why she is being warned off and cannot work out the connection surprised at the size of the prize: “I recently got a prize between the protagonists until her police officer boyfriend Luke drops strange in France which was a few bottles of wine.” hints about the case and about her commanding officers. -

Erskine Falls: a Crime Fiction Novel and Exegesis

Erskine Falls: a Crime Fiction Novel and Exegesis By CHRISTOPHER MALLON Student ID No: 983478X Dissertation submitted as fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy (Humanities) Swinburne University of Technology March 2020 Abstract This practice-led PhD consists of two elements – a crime fiction novel titled Erskine Falls, and an accompanying exegesis that critically situates the author’s creative practice and the production of the text. Drawing on the traditions of hardboiled detective fiction and noir crime fiction, the novel negotiates the spectrum between these two sub-genres and explores a world which questions the many modern articulations of masculinity. Erskine Falls is a contemporaneously-set novel that follows a private eye who investigates the case of a missing girl who is from the affluent resort town of Lorne, Victoria, Australia. As the private eye moves through Lorne’s world of seaside wealth and tourism, he is simultaneously coming to terms with the post-industrial changes in his own home town of Geelong and dealing with a tumultuous relationship with his deceased business partner’s wife. His investigation eventually leads him into an underground world of criminality that belies the smiling touristic face of Lorne. The exegesis reflexively explores key writerly choices and focuses on genre, masculinity, voice, and place. Building upon the hardboiled and noir crime fiction subgenres, the project seeks to examine how the traditional hardboiled voice and its masculinities are negotiated within a contemporary, post-industrial regional Australian space. Using a practice-led methodology, the exegesis reflexively aims to situate the novel in a contemporary world through the subgenres of hardboiled detective and noir crime fiction. -

William Legrand: a Study

William Legrand: A Study Joan Frances Holloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in November 2010 English, Media Studies, and Art History Declaration by author This thesis is composed of my original work, and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference has been made in the text. I have clearly stated the contribution by others to jointly-authored works that I have included in my thesis. I have clearly stated the contribution of others to my thesis as a whole, including statistical assistance, survey design, data analysis, significant technical procedures, professional editorial advice, and any other original research work used or reported in my thesis. The content of my thesis is the result of work I have carried out since the commencement of my research higher degree candidature and does not include a substantial part of work that has been submitted to qualify for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution. I have clearly stated which parts of my thesis, if any, have been submitted to qualify for another award. I acknowledge that an electronic copy of my thesis must be lodged with the University Library and, subject to the General Award Rules of The University of Queensland, immediately made available for research and study in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. I acknowledge that copyright of all material contained in my thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of that material. Statement of Contributions to Jointly Authored Works Contained in the Thesis No jointly-authored works.