Singer's Guide to Karol Szymanowski's Opera King

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ariadna En Naxos

RICHARD STRAUSS ARIADNA EN NAXOS STREAMING METROPOLITAN OPERA HOUSE Presenta RICHARD STRAUSS ARIADNA EN NAXOS Ópera en dos partes: Prólogo y Ópera Libreto de Hugo von Hofmannsthal, basado en “El burgués gentilhombre” de Molière y el mito griego de Ariadna y Baco. Reparto Ariadna - Prima Donna Jessye Norman Baco - Tenor James King Zerbinetta Kathleen Battle Compositor Tatiana Troyanos Maestro de música Franz Ferdinand Nentwig Arlequín Stephen Dickson Scaramuccio Allan Glassman Trufaldín Artur Korn Brighella Anthony Laciura Nayade Barbara Bonney Driada Gweneth Bean Echo Dawn Upshaw Mayordomo Nico Castel Coro y Orquesta del Metropolitan Opera House Dirección: James Levine Producción escénica Dirección teatral Bodo Igesz Escenografía Oliver Messel Vestuario Jane Greenwood Miércoles 13 de mayo de 2020 Transmisión vía streaming desde Metropolitan Opera House – New York, USA TEATRO NESCAFÉ DE LAS ARTES Temporada 2020 ARIADNA EN NAXOS ANTECEDENTES te el nombre de Hugo von Haffmannsthal, poeta, escritor y dramaturgo austriaco, quien creó los libretos de las más famo- sas producciones del compositor para la escena. Entre ellos los de la terna citada y el de “Ariadna en Naxos”, su sexta con- tribución para la lírica, con una gestación muy compleja. Strauss compuso la ópera “Ariadna en Naxos” en un acto y como homenaje a Max Reinhardt, quien fuera en 1911 el re- gisseur (director de escena) en el estreno mundial de “El caballero de la rosa”. “Ariadna en Naxos” se representó en Strauss y Hofmannsthal octubre de 1912 en el marco de una ce- remonia turca, inserta a su vez en el de- Junto al inglés Benjamin Britten (1913- sarrollo de una adaptación alemana de la 1976), Richard Strauss (1864-1949) forma la comedia “El burgués gentilhombre” de pareja de los más importantes y prolíficos Molière, hecha por Hoffmansthal. -

Exploiting Prior Knowledge During Automatic Key and Chord Estimation from Musical Audio

Exploitatie van voorkennis bij het automatisch afleiden van toonaarden en akkoorden uit muzikale audio Exploiting Prior Knowledge during Automatic Key and Chord Estimation from Musical Audio Johan Pauwels Promotoren: prof. dr. ir. J.-P. Martens, prof. dr. M. Leman Proefschrift ingediend tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Ingenieurswetenschappen Vakgroep Elektronica en Informatiesystemen Voorzitter: prof. dr. ir. R. Van de Walle Faculteit Ingenieurswetenschappen en Architectuur Academiejaar 2015 - 2016 ISBN 978-90-8578-883-6 NUR 962, 965 Wettelijk depot: D/2016/10.500/15 Abstract Chords and keys are two ways of describing music. They are exemplary of a general class of symbolic notations that musicians use to exchange in- formation about a music piece. This information can range from simple tempo indications such as “allegro” to precise instructions for a performer of the music. Concretely, both keys and chords are timed labels that de- scribe the harmony during certain time intervals, where harmony refers to the way music notes sound together. Chords describe the local harmony, whereas keys offer a more global overview and consequently cover a se- quence of multiple chords. Common to all music notations is that certain characteristics of the mu- sic are described while others are ignored. The adopted level of detail de- pends on the purpose of the intended information exchange. A simple de- scription such as “menuet”, for example, only serves to roughly describe the character of a music piece. Sheet music on the other hand contains precise information about the pitch, discretised information pertaining to timing and limited information about the timbre. -

Mariinsky Orchestra

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM A NOTES Friday, October 14, 2011, 8pm Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) fatalistic mockery of the enthusiasm with which Zellerbach Hall Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13, it was begun, this G minor Symphony was to “Winter Dreams” cause Tchaikovsky more emotional turmoil and physical suffering than any other piece he Composed in 1866; revised in 1874. Premiere of ever wrote. Mariinsky Orchestra complete Symphony on February 15, 1868, in On April 5, 1866, only days after he had be- Valery Gergiev, Music Director & Conductor Moscow, conducted by Nikolai Rubinstein; the sec- gun sketching the new work, Tchaikovsky dis- ond and third movements had been heard earlier. covered a harsh review in a St. Petersburg news- paper by César Cui of his graduation cantata, PROGRAM A In 1859, Anton Rubinstein established the which he had audaciously based on the same Russian Musical Society in St. Petersburg; a year Ode to Joy text by Schiller that Beethoven had later his brother Nikolai opened the Society’s set in his Ninth Symphony. “When I read this Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13, branch in Moscow, and classes were begun al- terrible judgment,” he later told his friend Alina “Winter Dreams” (1866; rev. 1874) most immediately in both cities. St. Petersburg Bryullova, “I hardly know what happened to was first to receive an imperial charter to open me.... I spent the entire day wandering aimlessly Reveries of a Winter Journey: Allegro tranquillo a conservatory and offer a formal -

Folk Roots, Urban Roots

Thursday 13 December 2018 7.30–9.55pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT FOLK ROOTS, URBAN ROOTS Bartók Hungarian Peasant Songs Szymanowski Harnasie Interval Stravinsky Ebony Concerto Osvaldo Golijov arr Gonzalo Grau Nazareno Bernstein Prelude, Fugue and Riffs ROOTS & Sir Simon Rattle conductor Edgaras Montvidas tenor Chris Richards clarinet Katia and Marielle Labèque pianos Gonzalo Grau percussion Raphaël Séguinier percussion London Symphony Chorus ORIGINS Simon Halsey chorus director In celebration of the life of Jeremy Delmar-Morgan Streamed live on youtube.com/lso Recorded by BBC Radio 3 for broadcast on Tuesday 18 December Welcome Jeremy Delmar-Morgan In Memory 1941–2018 We are also delighted to welcome Katia and Jeremy Delmar-Morgan was a member of Marielle Labèque, who perform Nazareno, the LSO Advisory Council for over 20 years, a double piano suite drawn from Osvaldo a Director of LSO Ltd from 2002 to 2013, and Golijov’s La Pasión según San Marco, thereafter a Trustee of the LSO Endowment arranged by Gonzalo Grau, who appears Trust. He was also Honorary President of alongside Raphaël Séguinier as one of this the Ronald Moore Sickness and Benevolent evening’s percussion soloists. We then close Fund, where he brought invaluable advice with Prelude, Fugue and Riffs by the LSO’s to the LSO musicians on the investment former President, Leonard Bernstein, with strategy for the fund. After studying LSO Principal Clarinet Chris Richards as soloist. medicine at Cambridge he went into the City for a career in stock-broking, latterly elcome to this LSO concert at Tonight’s concert is performed in combining the two in the financing of the Barbican. -

1. SUNSCREEN BOSSA NOVA I. Hand It Here, I Need to Rub My Legs

LIBRETTO 1. 3. SUNSCREEN BOSSA NOVA VACATIONERS’ CHORUS I. I. Hand it here, I need to rub my legs... TODAY THEY HAVE RAISED ‘Cause later they’ll peel and crack, THE RED AND YELLOW FLAG UP And chap. HIGH: THE WHIRLPOOLS OF THE SEA, Hand it I will rub you… DROP-OFFS, Otherwise, you’ll be red as a lobster… R IP-TIDES, UNDERTOWS. Hand it I will rub you… YOU’RE NOT ALLOWED TO WADE IN 2. DEEPER THAN YOUR KNEES! YOUNG MAN FROM THE VOLCANO COUPLE 4. SIREN’S ARIA I. I flew to a Portuguese corrida – I. A short trip, just for fun. The man I once married, But then the pilot had to land the plane My ex, he drowned in South-East Asia. in London: He was the best of swimmers, So I called up my friends On vacation with his girlfriend. And stayed over for a couple of days. To this very day, no one can understand And from that day on, how it could happen to him: Linda and I never been apart. Some say he was swimming out too far beyond the shore, Not a single climatologist predicted a And the deep waters took him in. scenario like this. Others, knowing him better, Maybe someone had a feeling – perhaps Claim he had suffered a cramp due to the bull?… a magnesium deficiency… …perhaps the bull?… 5. O la vida VACATIONERS’ CHORUS La vida... II. 8. YOU ARE STRONGLY ADVISED TO SONG OF EXHAUSTION. STAY ON SHORE, WORKAHOLIC’S SONG YOU SHOULD NOT LEAVE YOUR CHILDREN UNOBSERVED! I. -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

12-04-2018 Traviata Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI la traviata conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, production Michael Mayer based on the play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils set designer Christine Jones Tuesday, December 4, 2018 costume designer 8:00–11:00 PM Susan Hilferty lighting designer New Production Premiere Kevin Adams choreographer Lorin Latarro DEBUT The production of La Traviata was made possible by a generous gift from The Paiko Foundation Major additional funding for this production was received from Mercedes T. Bass, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,012th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S la traviata conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance violet ta valéry annina Diana Damrau Maria Zifchak flor a bervoix giuseppe Kirstin Chávez Marco Antonio Jordão the marquis d’obigny giorgio germont Jeongcheol Cha Quinn Kelsey baron douphol a messenger Dwayne Croft* Ross Benoliel dr. grenvil Kevin Short germont’s daughter Selin Sahbazoglu gastone solo dancers Scott Scully Garen Scribner This performance Martha Nichols is being broadcast live on Metropolitan alfredo germont Opera Radio on Juan Diego Flórez SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Tuesday, December 4, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Diana Damrau Chorus Master Donald Palumbo as Violetta and Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Juan Diego Flórez Liora Maurer, and Jonathan -

LIBRETTO LOOP” (Created by Todd Woodard)

OPERA WARM UP ACTIVITY: “LIBRETTO LOOP” (created by Todd Woodard) • OBJECTIVE: To build a foundational knowledge of some basic Opera terms through physical and vocal engagement, while simultaneously building energy and ensemble. • STARTING POSITION: A Standing Circle (or “Loop”) • Sample TA Intro: “What is Libretto? … Yes, Libretto might be the text of an opera, but those words are brought to life through music, movement, emotion and ENERGY. So in this game, we are going to use some Opera terms as our simple libretto, and share them by passing ENERGY through, across and within our LOOP, using music, movement, and emotion.” • TERMS with ACTIONS: o RECITATIVE: • Pass LIBRETTO Energy to the person next to you by singing the word “Recitative” to a TA-set or individualized melody with a directional clap • This continues in same direction until someone changes it with a different term o ARIA: “Hold onto the energy before you pass it by taking a solo moment in the spotlight” • Person sings “Aria! Aria! Aria!”, perhaps bending on a knee with arm outstretched, or striking another strong emotional pose • Then pass the energy with “Recitative” or with one of the terms below o VIBRATO • Person with energy shakes hands out in the direction of previous person to induce a vibrato in the voice while singing an extended “Vi- brAAAAA-TOOOOOO”) • This bounces the energy back to the previous person and they continue with energy pass in the opposite direction o MELODY • First person sings “Melody” to a melody of their choice as they pass it to another person -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2009

SUMMER 2009 • . BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR DALECHIHULY HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE 3 Elm Street, Stockbridge 413 -298-3044 www.holstengaIleries.com Olive Brown and Coral Pink Persian Set * for a Changing World They're Preparing to Change the 'I'Mi P i MISS HALL'S SCHOOL what girls have in mind 492 Holmes Road, Pittsfield, Massachusetts 01201 (413)499-1300 www.misshalls.org • e-mail: [email protected] m Final Weeks! TITIAN, TINTORETTO, VERONESE RIVALS IN RENAISSANCE VENICE " "Hot is the WOrdfor this show. —The New York Times Museum of Fine Arts, Boston March 15-August 16, 2009 Tickets: 800-440-6975 or www.mfa.ore BOSTON The exhibition is organized the Museum by The exhibition is PIONEER of Fine Arts, Boston and the Musee du sponsored £UniCredit Group by Investments* Louvre, and is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and Titian, Venus with a Mirror (detail), about 1555. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew the Humanities. W. Mellon Collection 1 937.1 .34. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington. James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 128th season, 2008-2009 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Edward H. Linde, Chairman • Diddy Cullinane, Vice-Chairman • Robert P. O'Block, Vice-Chairman Stephen Kay, Vice-Chairman • Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman • Edmund Kelly, Vice-Chairman • Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer • George D. Behrakis • Mark G. Borden • Alan Bressler • Jan Brett • Samuel B. Bruskin • Paul Buttenwieser • Eric D. -

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations. by Heewon Uhm A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Halen, Chair Professor Anthony D. Elliott Professor Freda A. Herseth Professor Andrew W. Jennings Assisant Professor Youngju Ryu Heewon Uhm [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8334-7912 © Heewon Uhm 2019 DEDICATION To God For His endless love To my dearest teacher, David Halen For inviting me to the beautiful music world with full of inspiration To my parents and sister, Chang-Sub Uhm, Sunghee Chun, and Jungwon Uhm For trusting my musical journey ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF EXAMPLES iv ABSTRACT v RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 9 Recital 2 Program 9 Recital 2 Program Notes 10 RECITAL 3 18 Recital 3 Program 18 Recital 3 Program Notes 19 BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 iii LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE Ex-1 Semachi Rhythm 15 Ex-2 Gutgeori Rhythm 15 Ex-3 Honzanori-1, the transformed version of Semachi and Gutgeori rhythm 15 iv ABSTRACT In lieu of a written dissertation, three violin recitals were presented. Recital 1: Theme and Variations Monday, November 5, 2018, 8:00 PM, Stamps Auditorium, Walgreen Drama Center, University of Michigan. Assisted by Joonghun Cho, piano; Hsiu-Jung Hou, piano; Narae Joo, piano. Program: Olivier Messiaen, Thème et Variations; Johann Sebastian Bach, Ciaconna from Partita No. -

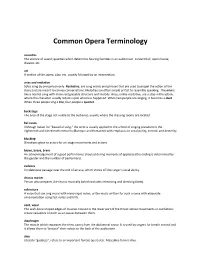

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

ELIJAH, Op. 70 (1846) Libretto: Julius Schubring English Translation

ELIJAH, Op. 70 (1846) Libretto: Julius Schubring Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847) English Translation: William Bartholomew PART ONE The Biblical tale of Elijah dates from c. 800 BCE. "In fact I imagined Elijah as a real prophet The core narrative is found in the Book of Kings through and through, of the kind we could (I and II), with minor references elsewhere in really do with today: Strong, zealous and, yes, the Hebrew Bible. The Haggadah supplements even bad-tempered, angry and brooding — in the scriptural account with a number of colorful contrast to the riff-raff, whether of the court or legends about the prophet’s life and works. the people, and indeed in contrast to almost the After Moses, Abraham and David, Elijah is the whole world — and yet borne aloft as if on Old Testament character mentioned most in the angels' wings." – Felix Mendelssohn, 1838 (letter New Testament. The Qu’uran also numbers to Julius Schubring, Elijah’s librettist) Elijah (Ilyas) among the major prophets of Islam. Elijah’s name is commonly translated to mean “Yahweh is my God.” PROLOGUE: Elijah’s Curse Introduction: Recitative — Elijah Elijah materializes before Ahab, king of the Four dark-hued chords spring out of nowhere, As God the Lord of Israel liveth, before Israelites, to deliver a bitter curse: Three years of grippingly setting the stage for confrontation.1 whom I stand: There shall not be dew drought as punishment for the apostasy of Ahab With the opening sentence, Mendelssohn nor rain these years, but according to and his court. The prophet’s appearance is a introduces two major musical motives that will my word.