The Making of Port Swettenham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation Via Analyzing Inhabitants' Garments of Early 19Th Century in Weld Quay

sustainability Article Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation via Analyzing Inhabitants’ Garments of Early 19th Century in Weld Quay, Malaysia Chen Kim Lim 1,*, Minhaz Farid Ahmed 1 , Mazlin Bin Mokhtar 1, Kian Lam Tan 2, Muhammad Zaffwan Idris 3 and Yi Chee Chan 3 1 Institute for Environment & Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 43600, Malaysia; [email protected] (M.F.A.); [email protected] (M.B.M.) 2 School of Digital Technology, Wawasan Open University, 54, Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah, George Town 10050, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Art, Computing & Creative Industry, Sultan Idris Education University, Tanjong Malim 35900, Malaysia; [email protected] (M.Z.I.); [email protected] (Y.C.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This qualitative study describes the procedures undertaken to explore the Intangible Culture Heritage (ICH) preservation, especially focusing on the inhabitants’ garments of different ethnic groups in Weld Quay, Penang, which was a multi-cultural trading port during the 19th century in Malaysia. Social life and occupational activities of the different ethnic groups formed the two main spines of how different the inhabitants’ garments would be. This study developed and demonstrated a step-by-step conceptual framework of narrative analysis. Therefore, the procedures used in this study are adequate to serve as a guide for novice researchers who are interested in undertaking Citation: Lim, C.K.; Ahmed, M.F.; a narrative analysis study. Hence, the investigation of the material culture has been exemplified Mokhtar, M.B.; Tan, K.L.; Idris, M.Z.; by proposing a novel conceptual framework of narrative analysis. -

13491-P) CIMB Islamic Bank Berhad 200401032872 (671380-H

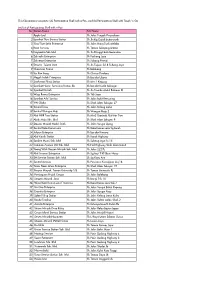

CIMB Bank Berhad 197201001799 (13491 -P) CIMB Islamic Bank Berhad 200401032872 (671380-H) Branches closed as at 31st March 2020 Please refer to below list of branches closed and the next nearest available branch: Branches Closed Next nearest available branch 1 CIMB Gleneagles Medini, Nusajaya Retail Branch CIMB Gelang Patah Lot 2, Jalan Medini Utara 4, Medini, 72950 Nusajaya, Retail Branch Johor Darul Takzim 25, Jalan Medan Nusa Perintis 6, Tel:07-5950388 Taman Nusa Perintis 2, 81550 Gelang Fax: 07-5950072 Patah, Johor Tel: 07-530 0000 Fax: 07-530 0017 CIMB Nusa Bestari Branch Retail Branch No 165 & 167, Jalan NB2 2/2 Taman Nusa Bistari 2, 81300 Skudai, Johor Tel: 07-554 8652 / 8471 / 8564 Fax: 07-554 8694 CIMB Perling Branch Retail Branch 382, Jalan Simbang, Taman Perling, 81200 Johor Bharu, Johor. Tel: 07-238 9770 / 6912 Fax: 07-238 0129 2 CIMB Riverson Kota Kinabalu CIMB Bundusan Square Retail Branch Retail Branch No. B-G-59 & B-1-83, Ground & 1st Floor, Lorong Lot 16 Bundusan Square, Jalan Riverson @ Sembulan Off Jalan Coastal, 88100 Kota Bundusan, 88300 Kota Kinabalu, Kinabalu, Sabah Sabah. Tel: 088-276 290 Tel: 088-732 611 / 613 / 614 / 615 Fax: 088-276 296 Fax: 088-732 618 CIMB Damai Plaza Retail Branch Lot No. 41 & 42, Ground Floor, Jalan Damai, Damai Plaza Phase 1, 88300 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Tel: 088 - 231144 and 088 – 231146 Fax: 088 – 231170 CIMB Jalan Sagunting Preferred Branch Tingkat Bawah, Central Building, Jalan Sagunting 88000 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Tel: 088-233 214 Fax: 088-242 794 CIMB Bank Berhad 197201001799 (13491 -P) CIMB Islamic Bank Berhad 200401032872 (671380-H) CIMB Inanam Retail Branch Lot 11-0, Inanam Point, Jalan Tuaran, 88450 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Tel: 088-439 734 / 731 Fax: 088-439 709 CIMB Api Api Centre Retail Branch API-API Centre, Lot 4/G3, 88000 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Tel: 088-264 287 Fax: 088-211 800 3 CIMB Teluk Panglima Garang CIMB Banting Retail Branch Retail Branch No. -

Klinik Panel Selangor

SENARAI KLINIK PANEL (OB) PERKESO YANG BERKELAYAKAN* (SELANGOR) BIL NAMA KLINIK ALAMAT KLINIK NO. TELEFON KOD KLINIK NAMA DOKTOR 20, JALAN 21/11B, SEA PARK, 1 KLINIK LOH 03-78767410 K32010A DR. LOH TAK SENG 46300 PETALING JAYA, SELANGOR. 72, JALAN OTHMAN TIMOR, 46000 PETALING JAYA, 2 KLINIK WU & TANGLIM 03-77859295 03-77859295 DR WU CHIN FOONG SELANGOR. DR.LEELA RATOS DAN RAKAN- 86, JALAN OTHMAN, 46000 PETALING JAYA, 3 03-77822061 K32018V DR. ALBERT A/L S.V.NICKAM RAKAN SELANGOR. 80 A, JALAN OTHMAN, 4 P.J. POLYCLINIC 03-77824487 K32019M DR. TAN WEI WEI 46000 PETALING JAYA, SELANGOR. 6, JALAN SS 3/35 UNIVERSITY GARDENS SUBANG, 5 KELINIK NASIONAL 03-78764808 K32031B DR. CHANDRAKANTHAN MURUGASU 47300 SG WAY PETALING JAYA, SELANGOR. 6 KLINIK NG SENDIRIAN 37, JALAN SULAIMAN, 43000 KAJANG, SELANGOR. 03-87363443 K32053A DR. HEW FEE MIEN 7 KLINIK NG SENDIRIAN 14, JALAN BESAR, 43500 SEMENYIH, SELANGOR. 03-87238218 K32054Y DR. ROSALIND NG AI CHOO 5, JALAN 1/8C, 43650 BANDAR BARU BANGI, 8 KLINIK NG SENDIRIAN 03-89250185 K32057K DR. LIM ANN KOON SELANGOR. NO. 5, MAIN ROAD, TAMAN DENGKIL, 9 KLINIK LINGAM 03-87686260 K32069V DR. RAJ KUMAR A/L S.MAHARAJAH 43800 DENGKIL, SELANGOR. NO. 87, JALAN 1/12, 46000 PETALING JAYA, 10 KLINIK MEIN DAN SURGERI 03-77827073 K32078M DR. MANJIT SINGH A/L SEWA SINGH SELANGOR. 2, JALAN 21/2, SEAPARK, 46300 PETALING JAYA, 11 KLINIK MEDIVIRON SDN BHD 03-78768334 K32101P DR. LIM HENG HUAT SELANGOR. NO. 26, JALAN MJ/1 MEDAN MAJU JAYA, BATU 7 1/2 POLIKLINIK LUDHER BHULLAR 12 JALAN KLANG LAMA, 46000 PETALING JAYA, 03-7781969 K32106V DR. -

This File Contains Two Parts: (A) Participating Shell with E-Pay, and (B) Participating Shell with Touch 'N Go

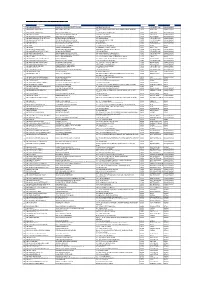

This file contains two parts: (A) Participating Shell with e-Pay, and (B) Participating Shell with Touch 'n Go (A) List of Participating Shell with e-Pay No Station Name Site Name 1 Apple Leaf Sh Jalan Tengah Perusahaan 2 Syarikat Thye Service Station Sh Jln Kg Gajah Butterworth 3 Eng Thye Setia Enterprise Sh Jalan Hang Tuah Melaka 4 Reza Services Sh Taman Selayang Utama 5 Dayapetro Sdn Bhd Sh Jln Pringgit Batu Berendam 6 Zahiedin Enterprise Sh Puchong Jaya 7 Zahienor Enterprise Sh Subang Permai 8 Stesyen Tujuan Jaya Sh Jln Tujuan Ss18 Subang Jaya 9 Chop Lian Seong Sh Balakong 10 Sin Kee Sang Sh Cheras Perdana 11 Megah Indah Enterprise Sh Bandar Utama 12 Saaharaa Filing Station Sh Mrr 2 Kepong 13 Syarikat Henry Servicing Station SB Sh Bandar Kuala Selangor 14 Syarikat Durrah Sh Jln Tuanku Abdul Rahman Kl 15 Waja Reena Enterprise Sh Ttdi Jaya 16 Syarikat Arbi Service Sh Jalan Bukit Kemuning 17 YW Global Sh Shah Alam Seksyen 27 18 Sentral Tiraz Sh Jalan Kelang Lama 19 Sentral Wangsa Maju Sh Wangsa Maju 2 20 Alaf MRR Two Station Sh Mrr2 Gombak Alaf Mrr Two 21 Abah Maju Sdn. Bhd. Sh Shah Alam Seksyen 9 22 Stesyen Minyak Mohd. Diah Sh Jalan Sungai Ujong 23 Sentral Kota Damansara Sh Kota Damansara Sg Buloh 24 Jufiyun Enterprise Sh Bandar Kinrara 25 Alaf Karak Station Sh Karak Highway 26 Spektra Murni Sdn. Bhd. Sh Subang Jaya Ss 15 27 Common Avenue (M) Sdn. Bhd. Sh Fed Highway Shah Alam Batu3 28 Yeong Wah Stesyen Minyak Sdn. -

The Maritime Potential of Penang

WORKING PAPER SERIES CenPRIS WP 142/11 THE MARITIME POTENTIAL OF PENANG Prof. Dr. Hans-Dieter Evers Mr. Sezali Md Darit OCTORBER 2011 Available online at http://www.usm.my/cenpris/ CenPRIS Working Paper No. 142/11 OCT 2011 Note: the paper is not meant to represent the views or opinions of CenPRIS or its Members. Any errors are the responsibility of the author(s). ABSTRACT 1 THE MARITIME POTENTIAL OF PENANG Location at the entrance /gateway to the Indian Ocean and its long coastline provide Penang State with a substantial maritime potential. The maritime potential and its utilization by a maritime economy have been captured by an index, developed by the Centre for Policy Research and International Studies, USM. Using data of the CenPRIS Ocean Index the paper will analyse the competitive position of Penang in relation to Singapore, Johor, Negeri Sembilan, Malacca, Selangor, Perak, Kedah and Perlis, all states along the Straits of Malacca. The question will be asked and at least partially answered, whether or not Penang has realized its maritime potential and has moved ahead of its competitors along the Straits of Malacca, serving as a gateway to the Indian Ocean. The development of the other maritime states will provide a benchmark, through which the performance of Penang can be measured. It will be argued that Penang’s maritime potential as a gateway to the Indian Ocean could be more fully realized and some of the connections across the Indian Ocean will be highlighted. KEYWORDS: Ocean Index, Maritime Economy, Development, Shipping, Fisheries, Malaysia Prof. Dr. Hans-Dieter Evers Mr. -

RSPO Audit Report

RSPO Principles & Criteria Annual Surveillance Assessment Report Report Number CU821295 RSPO PRINCIPLES & CRITERIA PUBLIC SUMMARY REPORT ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT 3 Malaysia KEKAYAAN PALM OIL MILL Kuala Lumpur-Kepong Berhad 2014 Report prepared by: Simon Selvaraj Subramaniam (Lead Assessor) Certification decision by: Nurhadi (Certifier) Certifying Office Control Union (Malaysia) Sdn. Bhd. 150-A, 1st Floor, Persiaran Raja Muda Musa, Off Jalan Sg Bertih, Teluk Gadong, 41100 Klang, Selangor, Malaysia [email protected] Tel: +603-3377 1600 / 1700 Control Union Certifications Control Union Certifications is a member of the Control Union World Group - an international inspection and certification body. CUC performs assessments and certification in many agricultural based fields such as FSC, RSPO, and Organic production, Sustainable Textile Production, Organic Exchange, GLOBALGAP, HACCP, BRC, GMP and GTP. CUC is accredited by the Dutch Council of Accreditation (RVA) on the European quality standard EN 45011 for the inspection and certification of CUC Organic program (according to the EU regulation 2092/91) and GLOBALGAP program. When requested a copy of the accreditation certificate can be obtained from CUC. RSPO Membership Number 8-0025-06-000-00 RSPO Approval Date 12/01/2006 Affiliate Membership http://www.rspo.org/en/member/339 RSPOPC-SUM-REPORT.F01 JULY2013 Page 1 of 41 Control Union (Malaysia) Sdn. Bhd. 150-A, 1st Floor, Persiaran Raja Muda Musa, Off Jalan Sg Bertih, Teluk Gadong, 41100, Klang, Selangor. Malaysia. Tel: +603-3377 1600 / 1700 RSPO Principles & Criteria Annual Surveillance Assessment Report Report Number CU821295 Table of Contents PART 1: SCOPE OF THE CERTIFICATION ASSESSMENT AUDIT .............................................................. 4 1.1 COMPANY AND CONTACT DETAILS ..................................................................................................... -

Shell Lebih Ekstra at Zalora Promotion Participating Stations List NO SITE

Shell Lebih Ekstra at Zalora Promotion Participating Stations List NO SITE NAME STATION NAME ADDRESS POSCODE CITY STATE 1 SH JALAN JELUTONG BAN LEONG SHELL PRODUCTS SDN BHD 347 JELUTONG ROAD 11600 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 2 SH BANDAR AYER ITAM 2 BBAI SHELL SERVICES LOT 2499 JALAN THEAN TEIK, JALAN SHAIK MADAR BANDAR 11500 AYER ITAM PULAU PINANG BARU 3 SH BANDAR AYER ITAM 1 BBAI SALES & SERVICES 12 ANGSANA FARLIM ROAD 11500 AYER ITAM PULAU PINANG 4 SH BUKIT GELUGOR BUKIT GLUGOR SERVICE STATION 210 BUKIT GELUGOR 11700 GELUGOR PULAU PINANG 5 SH JLN MAYANG PASIR BAYAN BARU CERGAS SAUJANA SDN BHD JALAN MAYANG PASIR 11950 BAYAN BARU PULAU PINANG 6 SH JALAN BURMAH GEORGE TOWN ELITEBAY EXPRESS ENTERPRISE 378 JALAN BURMA 10350 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 7 SH JALAN MESJID NEGERI GREEN ISLAND SERVICE STATION 4A JALAN MASJID NEGERI 11600 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 8 SH BALIK PULAU KEAN YOON FATT FILLING STATION 315 GENTING 11000 BALIK PULAU PULAU PINANG 9 SH WELD QUAY LEAN HONG CO SDN BHD 30 WELD QUAY 10300 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 10 SH GERIK MAESTRO ONE ENTERPRISE 122 JLN SULTAN ISKANDAR 33300 GERIK PERAK 11 SH LAWIN MEERA AAZ ENTERPRISE 2B KAMPUNG MALAU, LAWIN 33410 LENGGONG PERAK 12 SH JELUTONG EXPRESSWAY MILYAR MUTIARA ENTERPRISE LEBUHRAYA TUN DR LIM CHONG EU 11600 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 13 SH JALAN PERAK GEORGE TOWN MS MASHA ENTERPRISE 190 JALAN PERAK 10150 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 14 SH JALAN KELAWEI BIRCH MUKAH HEAD SERVICE STATION 2A JALAN KELEWAI / JALAN BIRCH 10250 GEORGETOWN PULAU PINANG 15 SH JALAN PAYA TERUBONG PAYA TERUBONG SERVICE STATION -

Rspo Principles & Criteria Public Summary Report

RSPO Principles & Criteria Annual Surveillance Assessment Report Report Number CU822632 RSPO PRINCIPLES & CRITERIA PUBLIC SUMMARY REPORT ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT 1 Malaysia TUAN MEE OIL MILL Kuala Lumpur-Kepong Berhad 2014 Report prepared by: Mahaswaran Maliyapan (Lead Assessor) Certification decision by: Gerben Stegeman (Certifier) Certifying Office Control Union (Malaysia) Sdn. Bhd. 150-A, 1st Floor, Persiaran Raja Muda Musa, Off Jalan Sg Bertih, Teluk Gadong, 41100 Klang, Selangor, Malaysia [email protected] Tel: +603 -3377 16 00 / 1700 Control Union Certifications Control Union Certifications is a member of the Control Union World Group - an international inspection and certification body. CUC performs assessments and certification in many agricultural based fields such as FSC, RSPO, and Organic production, Sustainable Textile Production, Organic Exchange, GLOBALGAP, HACCP, BRC, GMP and GTP. CUC is accredited by the Dutch Council of Accreditation (RVA) on the European quality standard EN 45011 for the inspection and certification of CUC Organic program (according to the EU regulation 2092/91) and GLOBALGAP program. When requested a copy of the accreditation certificate can be obtained from CUC. Control Union (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd is a registered affiliate member of RSPO and is a private limited company owned by the Control Union World Group based in Malaysia. Control Union (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd is authorized to conduct and issue certification on behalf of RSPO and Control Union Certifications. RSPO Membership Number 8-0025-06-000-00 RSPO Approval Date 12/01/2006 Affiliate Membership http://www.rspo.org/en/member/339 RSPOPC-SUM-REPORT.F01 JULY2013 Page 1 of 54 Control Union (Malaysia) Sdn. Bhd. -

Majlis Perbandaran Klang

HARGA DOKUMEN RM 40.00 MAJLIS PERBANDARAN KLANG DOKUMEN SEBUT HARGA KERJA UNTUK NO. SEBUT HARGA: MPK/JK 600-13/6/13 (2018) CADANGAN PENGGANTIAN TIANG LAMPU JENIS FIBER LELENGAN BERKEMBAR (DOUBLE ARM) KEPADA TIANG JENIS GALVANI (HOT DIPPED GALVANISED) DAN KERJA- KERJA MEMBAIKPULIH KESELURUHAN SISTEM KABEL DAN PENDAWAIAN DI PERSIARAN RAJA MUDA MUSA DARI SIMPANG JALAN KIM CHUAN HINGGA SIMPANG JALAN SUNGAI KELADI PELABUHAN KLANG. Pendaftaran : Sijil Perolehan Kerja Kerajaan (SSPK) oleh CIDB Unit Perancang Ekonomi Negeri Selangor (UPEN) E-Tender Negeri Selangor Gred : G2 Kategori / Pengkhususan : ME/ E11 & E04 Tarikh Iklan : 08.10.2018 Tarikh Lawatan : 12.10.2018 Tarikh Jualan : 16.10.2018 Tarikh Tutup S/harga : 22.10.2018 Tempoh Siap Kerja : 10 MINGGU Denda Lewat Siap Kerja : 0.5% daripada nilai kontrak bagi setiap hari kelewatan yang berlaku Penyata Bank : Julai 2018, Ogos 2018, September 2018 SENARAI SEMAKAN DOKUMEN TAWARAN SEBUT HARGA KERJA NO. FAIL : ........................................................................ Sila tandakan ( / ) bagi dokumen-dokumen yang disertakan. Bil. Perkara/Dokumen Untuk Di tanda Untuk Di tanda oleh Syarikat oleh Jawatankuasa Pembuka Sebut Harga 1 Salinan Resit Pembelian dokumen 2 Surat Akuan Pembida yang diisi lengkap – Lampiran A1 m/s 2/1/1 3 Borang Sebutharga Kerja yang diisi lengkap (termasuk nilai tawaran dan tempoh siap) serta ditandatangani dan bercop - m/s 5/1/1 4 Surat Pengakuan Kebenaran Maklumat Dan Keesahan Dokumen yang dikemukakan oleh penyebutharga telah diisi lengkap. – Borang A m/s A1 -

Senarai Semua Lokasi Hotspot Wifi Smart Selangor Adalah Seperti Berikut

Senarai semua lokasi hotspot WiFi Smart Selangor adalah seperti berikut:- No. Site Address Category 1 Masjid Nurul Yaqin Mosque Kampung Melayu Seri Kundang, 48050 Rawang, Selangor 2 Pusat Gerakan Khidmat Masyarakat (DUN Kuang) Government 6-1-A, Jalan 7A/2, Bandar Tasik Puteri, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 3 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014, 47000 Hospital Sungai Buloh Selangor 4 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 5 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 6 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 7 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 8 HOSPITAL SUNGAI BULOH_300014 Hospital 9 Perodua Service Centre Jln Sungai Pintas, No.14, Commercial Jalan TSB 10, Taman Industri Sg. Buloh 47000 Shah Alam selangor 10 TESCO RAWANG_300026, No.1, Jalan Rawang Mall 48000 Rawang Selangor 11 TM POINT RAWANG, TM Premises Lot 21, Jalan Maxwell 48000 Rawang 12 Stadium MPS, Jalan Persiaran 1, Bandar Baru Stadium Selayang, 68100 Batu Caves, Selangor 13 Pejabat Cawangan Rawang, Jalan Bandar Rawang Government 2, Bandar Baru Rawang, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 14 No. 309 Felda Sungai Buaya, 48010 Rawang, Residential Selangor area 15 Traffic Light Chicken Rice Sungai Choh, 48009 F&B outlet Rawang, Selangor 16 Pejabat Khidmat Rakyat (DUN Rawang) Government No.13, Jalan Bersatu 8 (Tingkat Bawah), Taman Bersatu, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 17 WTC Restoran F&B Outlet Rawang new town, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 18 Medan Selera MPS F&B Outlet Rawang Integrated Industrial Park, 45000 Rawang, Taman Tun Teja, Rawang, Selangor 19 Medan Selera F&B Outlet Bandar Country Homes, 48000 Rawang, Selangor 20 Kompleks JKKK, Selayang Baru, JKR 750C, Dewan Government Orang Ramai, Jalan Besar Selayang Baru, 68100 Batu Caves, Selangor 21 Pejabat Ahli Parlimen Selayang,12A, Jalan SJ 17, Government Taman Selayang Jaya, 68100 Batu Caves, Selangor No. -

14Th APCP and 4Th APCPN 2012

Report THE MALAYSIAN PAEDIATRIC ASSOCIATION NOV 2012 FOR MEMBERS ONLY Editorial Board 14th APCP and Datuk Dr Zulkifli Ismail Dr Yong Junina Fadzil th MPA 2011 – 2013 4 APCPN 2012 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia Dr Noor Khatijah Nurani Immediate Past President Prof Dr Zabidi Azhar Hussin Vice-President Dr Kok Chin Leong Secretary Assoc Prof Dr Tang Swee Fong Asst Secretary Dr Thiyagar Nadarajaw Treasurer Dato’ Dr Musa Mohd Nordin Committee Members Datuk Dr Zulkifli Ismail Dr Koh Chong Tuan Dr Hung Liang Choo Dr Ariffin Nasir Dr Selva Kumar Sivapunniam Joining in Sarawak cultural dance. Datuk Dr Soo Thian Lian Co-opted Committee Members Prof Datuk Mohd Sham Kasim Dato’ Dr Hussain Imam Haji Mohd Ismail The 14th Asia Pacific Congress book store, IPA Congress 2013 in Dato’ Dr Zakaria Zahari of Pediatrics and 4th Asia Pacific Melbourne, ACPID in Sri Lanka, and Affiliated to: Congress of Pediatric Nursing ended Habitat for Humanity Malaysia. • Malaysian Council For Child on 12th September after attracting Welfare 1284 registered delegates and MPA and APPA contribution to • ASEAN Pediatric Federation speakers, almost 60% of whom Sarawak were international delegates. The • Asian Pacific Pediatric Prior to the 14th APCP, the committee delegates came from 36 countries Association visited a house that was built by the excluding Malaysia and Singapore. – APPA (Previously Association of local Chapter of Habitat for Humanity Pediatric Societies of the South The Philippines and Thailand provided for a family to have a roof over -

Cruise Tourism : Malaysia's Experience

CRUISE TOURISM : MALAYSIA’S EXPERIENCE YONG EE CHIN Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Malaysia GLOBAL CRUISE KEY FIGURES CLIA Global Ocean Cruise Passengers 27.2 million (in millions) 27.2 passengers 25.8 24.7 22.34 23.06 expected to 21.3 cruise in 2018 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017p 2018p Capacity Share by Region South America 4.3% Alaska Others 4.3% 13.9% Caribbean Australia / New 35.6% Zealand / Pacific 6.0% Mediterranean 15.5% (Source: CLIA’s State of Asia Cruise Industry & Research Findings, Aug 2017) Cruise tourism in Asia Growing Strong Passenger Capacity Passenger Up to (million) cruise in 4.5 mil SEA by +29%* 4.24 2035 (Source: ASEAN’s Report on Cruise Development in Southeast Asia 2017) 1.51 Cruise Ships +11%* 66 43 2013 Cruises & Voyages 2017 +25%* 2,086 2013 861 2017 76%* 2013 2017 * = Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) (Source: CLIA’s State of Asia Cruise Industry & Research Findings, Aug 2017) 2017 TOTAL PORT CALLS BY DESTINATION 2378 1156 737 468 407 Port Calls Port Calls Port Calls Port Calls Port Calls JAPAN CHINA SOUTH KOREA MALAYSIA VIETNAM 393 509 263 295 187 Port Calls Port Calls Port Calls Port Calls Port Calls SINGAPORE THAILAND TAIWAN HONG KONG INDONESIA (Source: CLIA’s State of Asia Cruise Industry & Research Findings, Aug 2017) 2017 MOST VISITED ASIA PORTS 581 341 477 393 FUKUOKA/ 263 BAOSHAN/ JEJU ISLAND SINGAPORE HONG KONG SHANGHAI HAKATA CHINA SOUTH KOREA SINGAPORE JAPAN HONG KONG 237 213 207 247 KEELUNG/ NAHA/ GEORGETOWN/ 205 NAGASAKI PUSAN/BUSAN TAIPEI OKINAWA PENANG JAPAN TAIWAN JAPAN MALAYSIA SOUTH KOREA (Source: