University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hills of Dreamland

SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857-1934) The Hills of Dreamland SOMMCD 271-2 The Hills of Dreamland Orchestral Songs The Society Complete incidental music to Grania and Diarmid Kathryn Rudge mezzo-soprano† • Henk Neven baritone* ELGAR BBC Concert Orchestra, Barry Wordsworth conductor ORCHESTRAL SONGS CD 1 Orchestral Songs 8 Pleading, Op.48 (1908)† 4:02 Song Cycle, Op.59 (1909) Complete incidental music to 9 Follow the Colours: Marching Song for Soldiers 6:38 1 Oh, soft was the song (No.3) 2:00 *♮ * (1908; rev. for orch. 1914) GRANIA AND DIARMID 2 Was it some golden star? (No.5) 2:44 * bl 3 Twilight (No.6)* 2:50 The King’s Way (1909)† 4:28 4 The Wind at Dawn (1888; orch.1912)† 3:43 Incidental Music to Grania and Diarmid (1901) 5 The Pipes of Pan (1900; orch.1901)* 3:46 bm Incidental Music 3:38 Two Songs, Op. 60 (1909/10; orch. 1912) bn Funeral March 7:13 6 The Torch (No.1)† 3:16 bo Song: There are seven that pull the thread† 3:33 7 The River (No.2)† 5:24 Total duration: 53:30 CD 2 Elgar Society Bonus CD Nathalie de Montmollin soprano, Barry Collett piano Kathryn Rudge • Henk Neven 1 Like to the Damask Rose 3:47 5 Muleteer’s Serenade♮ 2:18 9 The River 4:22 2 The Shepherd’s Song 3:08 6 As I laye a-thynkynge 6:57 bl In the Dawn 3:11 3 Dry those fair, those crystal eyes 2:04 7 Queen Mary’s Song 3:31 bm Speak, music 2:52 BBC Concert Orchestra 4 8 The Mill Wheel: Winter♮ 2:27 The Torch 2:18 Total duration: 37:00 Barry Wordsworth ♮First recordings CD 1: Recorded at Watford Colosseum on March 21-23, 2017 Producer: Neil Varley Engineer: Marvin Ware TURNER CD 2: Recorded at Turner Sims, Southampton on November 27, 2016 plus Elgar Society Bonus CD 11 SONGS WITH PIANO SIMS Southampton Producer: Siva Oke Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Booklet Editor: Michael Quinn Front cover: A View of Langdale Pikes, F. -

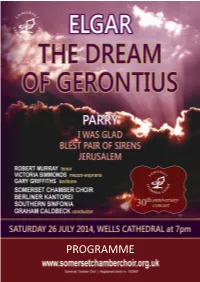

To View the Concert Programme

PROGRAMME Happy birthday Somerset Chamber Choir! Welcome to our 30th birthday party! We are delighted that our very special invited guests, our loyal choir ‘Friends’ and everyone here tonight could join us for this occasion. As if that weren’t enough of a nucleus for a wonderful party, the BERLINER KANTOREI have travelled from Berlin to celebrate with us too ... their ‘return match’ for an excellent time some of us enjoyed singing with them when they hosted us last autumn. This concert comes at the end of a week which their party of singers and supporters have spent staying in and sampling the delights of Somerset; we hope their experience has been a memorable one and we wish them bon voyage for their journey home. Ten years of singing together in the 1970s and 1980s under the inspirational direction of the late W. Robert Tullett, founder conductor of the Somerset Youth Choir, welded a disparate group of young people drawn from schools across Somerset, into a close-knit group of friends who had discovered the huge pleasure of making music together and who developed a passion for choral music that they wanted to share. The Somerset Chamber Choir was founded in 1984 when several members who had become too old to be classed as “youths” left the Youth Choir and, with the approval of Somerset County Council, drew together other like-minded singers from around the County. Blessed with a variety of complementary skills, a small steering group set about developing a balanced choir and appointed a conductor, accompanist and management team. -

Christoph Eschenbach Dirigiert Mahler 6

Eschenbach dirigiert Mahler 6 Samstag, 08.04.17 — 19.30 Uhr Lübeck, Musik- und Kongresshalle GUSTAV MAHLER Sinfonie Nr. 6 a-Moll ChristopH ESchenbAcH Dirigent „Glück flammt hoch am Rande des Grauens“ Am 20. Mai 1906 machte sich Gustav Mahler auf die Meine VI. wird Reise nach Essen, um die Uraufführung seiner Sechs Rätsel aufgeben, ten Sinfonie vorzubereiten – mit gemischten Gefüh len. Denn zum einen zweifelte er an der Leistungs an die sich nur fähigkeit des Essener Orchesters, das qualitativ dem eine Generation Kölner GürzenichOrchester, mit dem er zwei Jahre zuvor seine Fünfte erarbeitet hatte, klar unterlegen heranwagen darf, NDR ELbpHilharmoNiE war. Zum anderen hatte man aufgrund der großen die meine ersten Orchester Besetzung das Orchester der Stadt Utrecht zur Verstär kung holen müssen, über dessen Güte sich Mahler fünf in sich auf- zuvor bei seinem Freund Willem Mengelberg zwar genommen hat. ausführlich erkundigt hatte und beruhigt worden war. Doch würden sich beide Orchester problemlos zu Gustav Mahler im Jahr 1904 einem Klangkörper zusammenfügen lassen? Mahlers Bedenken sollten sich als unbegründet erweisen. „Sehr zufrieden von der 1. Probe!“, heißt es Gustav Mahler (1860 – 1911) in einem Brief an Alma Mahler vom 2. Mai 1906. Sinfonie Nr. 6 aMoll „Orchester hält sich famos und klingen thut Alles, Entstehung: 1903 – 04 | Uraufführung: Essen, 27. Mai 1906 | Dauer: ca. 85 Min. wie ich es wünschen kann.“ Dennoch wurde die Pre I. Allegro energico, ma non troppo. miere am 27. Mai 1906 im Essener Saalbau nur ein Heftig, aber markig Achtungserfolg, bei dem laut den Erinnerungen des II. Scherzo. Wuchtig – Trio. Altväterisch, grazioso damals anwesenden Dirigenten Klaus Pringsheim III. -

International Choral Bulletin Is the Official Journal of the IFCM

2011-2 ICB_ICB New 5/04/11 17:49 Page1 ISSN 0896 – 0968 Volume XXX, Number 2 – 2nd Quarter, 2011 ICB International CIhoCral BulBletin First IFCM International Choral Composition Competition A Great Success! Results and Interview Inside Dossier Choral Music in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Macau 2011-2 ICB_ICB New 5/04/11 17:49 Page2 International Federation for Choral Music The International Choral Bulletin is the official journal of the IFCM. It is issued to members four times a year. Managing Editor Banners Dr Andrea Angelini by Dolf Rabus on pages 22, 66 & 68 Via Pascoli 23/g 47900 Rimini, Italy Template Design Tel: +39-347-2573878 - Fax: +39-2-700425984 Marty Maxwell E-mail: [email protected] Skype: theconductor Printed by Imprimerie Paul Daxhelet, B 4280 Avin, Belgium Editor Emerita Jutta Tagger The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of IFCM. Editorial Team Michael J. Anderson, Philip Brunelle, Submitting Material Theodora Pavlovitch, Fred Sjöberg, Leon Shiu-wai Tong "When submitting documents to be considered for publication, please provide articles by CD or Email. Regular Collaborators The following electronic file formats are accepted: Text, Mag. Graham Lack – Consultant Editor RTF or Microsoft Word (version 97 or higher). ([email protected] ) Images must be in GIF, EPS, TIFF or JPEG format and be at Dr. Marian E. Dolan - Repertoire least 350dpi. Articles may be submitted in one or more of ([email protected] ) these languages: English, French, German, Spanish." Dr. Cristian Grases - World of Children’s and Youth Choirs ( [email protected] ) Reprints Nadine Robin - Advertisement & Events Articles may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes ([email protected] ) once permission has been granted by the managing Dr. -

Vol. 18, No. 1 April 2013

Journal April 2013 Vol.18, No. 1 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2013 Vol. 18, No. 1 Editorial 3 President Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Julia Worthington - The Elgars’ American friend 4 Richard Smith Vice-Presidents Redeeming the Second Symphony 16 Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Tom Kelly Diana McVeagh Michael Kennedy, CBE Variations on a Canonical Theme – Elgar and the Enigmatic Tradition 21 Michael Pope Martin Gough Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Music reviews 35 Leonard Slatkin Martin Bird Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Donald Hunt, OBE Book reviews 36 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Frank Beck, Lewis Foreman, Arthur Reynolds, Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE D reviews 44 Martin Bird, Barry Collett, Richard Spenceley Chairman Letters 53 Steven Halls Geoffrey Hodgkins, Jerrold Northrop Moore, Arthur Reynolds, Philip Scowcroft, Ronald Taylor, Richard Turbet Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago 57 Treasurer Clive Weeks The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Secretary nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Helen Petchey Front Cover: Julia Worthington (courtesy Elgar Birthplace Museum) Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Editorial required, are obtained. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

78R1 MF 0518.Pdf

CONTENTS CONCERTS ARTISTS 38 Verdi REQUIEM: Friday May 18 19 Juanjo Mena, Principal Conductor 21 Robert Porco, Director of Choruses 46 Bernstein MASS: Saturday May 19 22 May Festival Chorus May Festival Youth Chorus, SING HALLELUJAH: Sunday May 20 27 56 James Bagwell, director 59 JUANJO MENA’S DEBUT: 30 Guest Conductor, Guest Artists Friday May 25 36 Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Handel MESSIAH: Saturday May 26 67 FEATURES 12 Bernstein’s MASS, Then and Now 15 Celebrating the Musical Legacy of Leonard Bernstein 16 About Otxote Txanbela 17 Q&A with Juanjo Mena 22 Q&A with Robert Porco 29 Q&A with James Bagwell 57 Q&A with Creative Partner Rollo Dilworth DEPARTMENTS 7 Greetings from the Principal Conductor 8 Your Concert Experience 11 Greetings from the Board Chair and Executive Director 75 In Memoriam 76 Choral Student Fund and ArtsWave Partners 76 Special Thanks 77 Cincinnati Musical Festival Association 79 Annual Fund 81 2017 ArtsWave Community Campaign 82 May Festival Subscribers 84 Administration 2 | MAY FESTIVAL 2018 | mayfestival.com MAY FESTIVAL PROGRAM BOOK STAFF: Vice President of Communications Chris Pinelo Director of Communications Diana Maria Lara Communications Assistant Kayla Moore Editor/Layout McKibben Publications Graphic Designer Regina Kuhns All contents © 2018. The contents cannot be reproduced in any manner, whole or in part, without written permission from the May Festival. CINCINNATI MAY FESTIVAL Music Hall Geraldine V. Chavez Center for the Choral Arts ON THE COVER 2018 marks a true 1241 Elm Street homecoming for the May Festival, as it returns to Cincinnati, OH 45202 the beautifully renovated Music Hall—a treasured Administrative Offices: 513.621.1919 National Historic Landmark that was originally [email protected] constructed for the May Festival. -

November 10 - 13, 2015 Thank You to Organizations and Individuals Whose Support Made This Event Possible

November 10 - 13, 2015 Thank You to Organizations and Individuals Whose Support Made this Event Possible Event Sponsors Fairchild Books and Bloomsbury Publishing Fashion Supplies Lectra Paris American Academy Award Sponsors Alvanon ATEXINC Cotton Incorporated Eden Travel International Educators for Responsible Apparel Practices Fashion Supplies Intellect Books Lectra Optitex Regent’s University London Vince Quevedo and ITAA Members who have contributed to ITAA Development Funds Conference Chairs especially want to thank the following individuals: Laurie McAlister Apple Kim Hiller Young-A Lee Ellen McKinney Genna Reeves-DeArmond Diana Saiki Mary Ruppert-Stroescu and all the dozens of ITAA volunteers! Conference Program Sponsored by Paris American Academy Introduction Headings Link to Detailed Information WELCOME TO THE ITAA 2015 ANNUAL CONFERENCE CONFERENCE MEETING SPACE ITAA 2015 DISTINGUISHED FACULTY AWARD WINNERS ITAA 2015 KEYNOTE LECTURERS ITAA 2015 THEME SESSION SPEAKERS ITAA SPONSOR PAGES ITAA MEMBER PROGRAM PAGES CONFERENCE SCHEDULE (details & links on following pages) RESOURCE EXHIBITOR LIST CAREER FAIR PARTICIPANT LIST REVIEW AND PLANNING COMMITTEES 2015 ITAA COUNCIL MEMBERS Tuesday at a Glance 7:30am-7:00pm Registration Open Concourse 8:00am-6:00pm Projector Practice and Poster Preparation De Vargas 9:00am-5:00pm Accreditation Commission Meeting Chaparral Boardroom, 3rd floor 8:30am-12:30pm Workshop: Leadership in Academia Zia B 9:00am-4:00pm Tour: Taos: Fashion, Pueblo, and a Unique Resident 10:00am-3:00pm Tour: Museum of International -

First Weekend of 2016 May Festival (May 20-22) Features Award

Chris Pinelo Vice President of Communications [email protected] (513) 744-3338 Meghan Berneking Director of Communications [email protected] (513) 744-3258 mayfestival.com For Immediate Release First weekend of 2016 May Festival (May 20-22) features award- winning soloists, two world premieres, rich choral music 2016 Festival honors Maestro James Conlon’s extraordinary 37-year tenure CINCINNATI, OH – The 2016 May Festival, which celebrates and concludes Music Director James Conlon’s 37-year tenure, kicks off on Friday, May 20 (8 p.m.) at Cincinnati Music Hall with Mozart’s exquisite “Great” Mass in C minor. With its grandiose choruses, pristine virtuosity for soloists and soaring expressiveness, this is one of the composer’s most-beloved works. Also on the program are Mozart’s Ave verum corpus and Exsultate jubilate. Soprano Lisette Oropesa, mezzo-soprano Elizabeth DeShong (who has recently received rave reviews for her recent performances as Calbo in Maometto at the Canadian Opera Company), tenor Ben Bliss and baritone John Cheek bring their artistry to these masterpieces along with the May Festival Chorus (professionally-trained chorus composed primarily of dedicated volunteer singers from around the Tri-state) and Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, all led by Maestro Conlon. On the second day of the Festival (8 p.m. Saturday, May 21 at Music Hall), jealousy, deceit and passion fuel Verdi’s epic Otello. Mr. Conlon has long held an affinity for Verdi’s operas, and first conducted a complete Otello with the May Festival in 1987. Bringing Shakespeare’s characters to life alongside the May Festival Chorus and CSO are tenor Gregory Kunde (Otello), soprano Tamara Wilson (Desdemona), baritone Egils Silins (Iago), tenor Ben Bliss (Cassio), mezzo-soprano Sara Murphy (Emilia), tenor Rodrick Dixon (Roderigo) and baritone John Cheek (Lodovico, Montano, the Herald). -

View/Download Liner Notes

HUBERT PARRY SONGS OF FAREWELL British Choral Music remarkable for its harmonic warmth and melodic simplicity. Gustav Holst (1874-1934) composed The Evening- 1 The Evening-Watch Op.43 No.1 Gustav Holst [4.59] Watch, subtitled ‘Dialogue between the Body Herbert Howells (1892-1983) composed his Soloists: Matthew Long, Clare Wilkinson and the Soul’ in 1924, and conducted its first memorial anthem Take him, earth, for cherishing 2 A Good-Night Richard Rodney Bennett [2.58] performance at the 1925 Three Choirs Festival in late 1963 as a tribute to the assassinated 3 Take him, earth, for cherishing Herbert Howells [9.02] in Gloucester Cathedral. A setting of Henry President John F Kennedy, an event that had moved Vaughan, it was planned as the first of a series him deeply. The text, translated by Helen Waddell, 4 Funeral Ikos John Tavener [7.41] of motets for unaccompanied double chorus, is from a 4th-century poem by Aurelius Clemens Songs of Farewell Hubert Parry but only one other was composed. ‘The Body’ Prudentius. There is a continual suggestion in 5 My soul, there is a country [3.52] is represented by two solo voices, a tenor and the poem of a move or transition from Earth to 6 I know my soul hath power to know all things [2.04] an alto – singing in a metrically free, senza Paradise, and Howells enacts this by the way 7 Never weather-beaten sail [3.22] misura manner – and ‘The Soul’ by the full his music moves from unison melody to very rich 8 There is an old belief [4.52] choir. -

FLORIDA Fulton Ma^Rae, a Broker the M^Rrl-Sj and Gustaviv! of Utcllcsl Tales Rv»R No

5 NEW-YORK DAILY TRIBI M;, MONOVV, FEBRUARY 2t 1010. we find there is not even a loaf ef bread j in th- house." In «M case a member of j U.S. COURTS CHOKED noFAxrrr decried. cupboard literally | CLINCH RLEF CASE Of Interest to Women this branch found the WASHINGTON bare- She left a trifle, and th* husband. j Clergyman to Na- had earned f*> cents that day. cam" In Washington carved a consti- Sees Danger who th«y PUSHED. and said. "Wak» up. the children." for tution out of chaos. WISE HJED PROSEC to .«upperles.«. 'Hi- wife re- tion in Its Spread. AIM OF TTOF. WHITE CLOTH SUITS had gone bed bequeathed to his M they *af | He also The n^v Dr. William Carter, in his morn- plied. "I>t them sleep, because ms be nothing *i»-morrow." countrymen this advice: sermon yesterday at the Madison Ave- to-night there will j Only One Judge Prose- nue Reformed that irrev- The president of No. 11 branch pay* on* "To be prepared for war is for Church declared Now Nothing brace?, to 'vrwrfl and blasphemy have emptied the Seeks Indictments for Smarter Has Been of her nursery children \u25a0•«•* most effectual means hard one of the cutor's 260 Cases. churches and are threatening to wreck the straighten its legs. Th" mother iia preserving peace." Health Laic Violation*. woman, pay , of nation. Shown This Season. working who -will somethin*. of H»nry A. Wise, United States Attorney "This the whole expense. An- That is an elaboration the hi a light, flippant and frivolous The presentation of the f°r but cannot meet District of New York, 1* age.*' indictments Nothing i3i3 nursery able la j says prevention for th» Southern said Dr. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec.