Run to Glory and Profits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

Tony Adamle: Doctor of Defense

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 24, No. 3 (2002) Tony Adamle: Doctor of Defense By Bob Carroll Paul Brown “always wanted his players to better themselves, and he wanted us known for being more than just football players,” Tony Adamle told an Akron Beacon Journal reporter in 1999. In the case of Adamle, the former Cleveland Browns linebacker who passed away on October 8, 2000, at age 76, his post-football career brought him even more honor than captaining a world championship team. Tony was born May 15, 1924, in Fairmont, West Virginia, to parents who had immigrated from Slovenia. By the time he reached high school, his family had moved to Cleveland where he attended Collinwood High. From there, he moved on to Ohio State University where he first played under Brown who became the OSU coach in 1941. World War II interrupted Adamle’s college days along with those of so many others. He joined the U.S. Air Force and served in the Middle East theatre. By the time he returned, Paul Bixler had succeeded Paul Brown, who had moved on to create Cleveland’s team in the new All-America Football Conference. Adamle lettered for the Buckeyes in 1946 and played well enough that he was selected to the 1947 College All-Star Game. He started at fullback on a team that pulled off a rare 16-0 victory over the NFL’s 1946 champions, the Chicago Bears. Six other members of the starting lineup were destined to make a mark in the AAFC, including the game’s stars, quarterback George Ratterman and running back Buddy Young. -

Nagurski's Debut and Rockne's Lesson

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 20, No. 3 (1998) NAGURSKI’S DEBUT AND ROCKNE’S LESSON Pro Football in 1930 By Bob Carroll For years it was said that George Halas and Dutch Sternaman, the Chicago Bears’ co-owners and co- coaches, always took opposite sides in every minor argument at league meetings but presented a united front whenever anything major was on the table. But, by 1929, their bickering had spread from league politics to how their own team was to be directed. The absence of a united front between its leaders split the team. The result was the worst year in the Bears’ short history -- 4-9-2, underscored by a humiliating 40-6 loss to the crosstown Cardinals. A change was necessary. Neither Halas nor Sternaman was willing to let the other take charge, and so, in the best tradition of Solomon, they resolved their differences by agreeing that neither would coach the team. In effect, they fired themselves, vowing to attend to their front office knitting. A few years later, Sternaman would sell his interest to Halas and leave pro football for good. Halas would go on and on. Halas and Sternaman chose Ralph Jones, the head man at Lake Forest (IL) Academy, as the Bears’ new coach. Jones had faith in the T-formation, the attack mode the Bears had used since they began as the Decatur Staleys. While other pro teams lined up in more modern formations like the single wing, double wing, or Notre Dame box, the Bears under Jones continued to use their basic T. -

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects an Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) By Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2004 May 8, 2004 Abstract The history of baseball in the United States during the twentieth century in many ways mirrors the history of our nation in general. When the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left New York for California in 1957, it had very interesting repercussions for New York. The vacancy left by these two storied baseball franchises only spurred on the reason why they left. Urban decay and an exodus of middle class baseball fans from the city, along with the increasing popularity of television, were the underlying causes of the Giants' and Dodgers' departure. In the end, especially in the case of Brooklyn, which was very attached to its team, these processes of urban decay and exodus were only sped up when professional baseball was no longer a uniting force in a very diverse area. New York's urban demographic could no longer support three baseball teams, and California was an excellent option for the Dodger and Giant owners. It offered large cities that were hungry for major league baseball, so hungry that they would meet the requirements that Giants' and Dodgers' owners Horace Stoneham and Walter O'Malley had asked for in New York. These included condemnation of land for new stadium sites and some city government subsidization for the Giants in actually building the stadium. Overall, this research shows the very real impact that sports has on its city and the impact a city has on its sports. -

Eagles' Team Travel

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019-2020 EDITIOn PHILADELPHIA EAGLES Team History The Eagles have been a Philadelphia institution since their beginning in 1933 when a syndicate headed by the late Bert Bell and Lud Wray purchased the former Frankford Yellowjackets franchise for $2,500. In 1941, a unique swap took place between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh that saw the clubs trade home cities with Alexis Thompson becoming the Eagles owner. In 1943, the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh franchises combined for one season due to the manpower shortage created by World War II. The team was called both Phil-Pitt and the Steagles. Greasy Neale of the Eagles and Walt Kiesling of the Steelers were co-coaches and the team finished 5-4-1. Counting the 1943 season, Neale coached the Eagles for 10 seasons and he led them to their first significant successes in the NFL. Paced by such future Pro Football Hall of Fame members as running back Steve Van Buren, center-linebacker Alex Wojciechowicz, end Pete Pihos and beginning in 1949, center-linebacker Chuck Bednarik, the Eagles dominated the league for six seasons. They finished second in the NFL Eastern division in 1944, 1945 and 1946, won the division title in 1947 and then scored successive shutout victories in the 1948 and 1949 championship games. A rash of injuries ended Philadelphia’s era of domination and, by 1958, the Eagles had fallen to last place in their division. That year, however, saw the start of a rebuilding program by a new coach, Buck Shaw, and the addition of quarterback Norm Van Brocklin in a trade with the Los Angeles Rams. -

Bee Gee News August 6, 1947

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 8-6-1947 Bee Gee News August 6, 1947 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "Bee Gee News August 6, 1947" (1947). BG News (Student Newspaper). 826. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/826 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. O'HH •<>!• ( "- N LIBRARY All IJM News that. Wc Print Bee Qee ^IIMOTIII ,0**- Official Stad«l PubJtcatWn M BuwS»g Green State OalTenrrr VOLUME XXXI BOWLING GREEN, OHIO, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 6, 1947 NUMBER 11 Speech Department Enrollment Record Adds Graduate Work Predicted For Fall Dr. C. H. Wesley Speaks To Fall Curriculum Four thousand to 4,200 students are expected to set an all-time en- At Commencement Friday A graduate program has been rollment record this fall, John W. established for next year which Bunn, registrar, said this week. Dr. Charles H. Wesley, president of the state-sponsored will result in changes in the cur- The previous high for the Uni- College of Education and Industrial Arts at Wilberforce Uni- riculum of the speech department. versity was 3,9,18. versity, will be the Commencement speaker for the summer- term graduation to be held Friday, Aug. -

Bill Willis: Dominant Defender

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 16, No. 5 (1994) BILL WILLIS: DOMINANT DEFENDER By Bob Carroll Bill Willis was one of the most dominant defensive linemen to play pro football after World War II. His success helped open the doors of the pro game for other Afro-Americans. William K. Willis was born October 5, 1921 in Columbus, Ohio, the son of Clement and Willana Willis. His father died when he was four, and he was raised by his grandfather and mother. He attended Columbus East High School and at first was more interested in track than football. "I had a brother, Claude, who was about six years older than me," Willis says. "He was an outstanding football player, a fullback in high school and I was afraid I would be compared with him." When he finally went out for football, he chose to play in the line despite the great speed that seemingly destined him for the backfield. He was a three-year regular at Columbus East, winning Honorable Mention All-State honors in his senior year. After working a year, Willis entered Ohio State University in 1941 and quickly caught the eye of Coach Paul Brown. At 6-2 but only 202 pounds, he was small for a tackle on a major college team, but his quickness made him a regular as a sophomore. At season's end, the 9-1 Buckeyes won the 1942 Western Conference (Big 10) championship and were voted the number one college team in the country by the Associated Press. Wartime call-ups hurt the team in Willis' final two years as most of OSU's experienced players as well as Coach Brown went into the service, but his own reputation continued to grow. -

On Arrest of Sit-Ins

Fair, cold tonight. Low !• to 24. Increasing ^oudiaess Tnssdajr, Highest temperatare In 40s. Manchester— A City of Village Charm -------------- ■ VDL. LXXX, NO. 143 TOURTEEN PAGES— PLUS TWELVE PAGE TABLOID MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, MARCH 20, 1961 (ClMiUied Advertltlng on Page IS) PRICE FIVE CENTS Blacks, Whites Riot State News Kennedy Seeks Roundup $500 Million In Johannesburg as Budget Bpifet I Autopsy Shows Washington, March 20 (/P) Voerwoerd Returns —President Kennedy, askeci Driver, 60, Died Congress today to boost ne.xt Johannesburer, South Afri-t At the same time, security po Of Lung Injury year’s budget by nearly $500 ca, March 20 (/P)— Fighting lice in nationwide raids arrested million. broke out between blacks and 10 African NationaUst leaders to He sought', among other things, On Arrest of Sit-ins head off possible demonstrations Groton, March 20 (^)—The additional, funds to step up State whites outside Johannesburg tomorrow, first anniversary of the death of a motorist who was Department activities in Africa, City Hall today as Prime Min day white police killed 60 Africans being held in a cell at the strengthen the U.S. Information ister Hendrik F. Verwoerd re and wounded 180 others at Sharpe- Agency’s program in Africa and vllle. State Police Troop here has Latin America and expand the Louisiana’s turned from a conference in Verwoerd was met at Jan Smuts been attribnted to a build-up U.S. staff at the United Nations. London during which he an Airport, 15 miles outside Johanes- of fluid in his lungs as a re Kennedy also proposed increases nounced South Africa is leav burg, by lieveral thousand whites. -

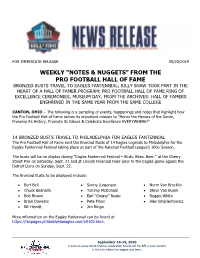

“Notes & Nuggets” from the Pro

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 09/20/2019 WEEKLY “NOTES & NUGGETS” FROM THE PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME BRONZED BUSTS TRAVEL TO EAGLES FANTENNIAL; BILLY SHAW TOOK PART IN THE HEART OF A HALL OF FAMER PROGRAM; PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME RING OF EXCELLENCE CEREMONIES; MUSEUM DAY; FROM THE ARCHIVES: HALL OF FAMERS ENSHRINED IN THE SAME YEAR FROM THE SAME COLLEGE CANTON, OHIO – The following is a sampling of events, happenings and notes that highlight how the Pro Football Hall of Fame serves its important mission to “Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE!” 14 BRONZED BUSTS TRAVEL TO PHILADELPHIA FOR EAGLES FANTENNIAL The Pro Football Hall of Fame sent the Bronzed Busts of 14 Eagles Legends to Philadelphia for the Eagles Fantennial Festival taking place as part of the National Football League’s 100th Season. The busts will be on display during “Eagles Fantennial Festival – Birds. Bites. Beer.” at the Cherry Street Pier on Saturday, Sept. 21 and at Lincoln Financial Field prior to the Eagles game agains the Detroit Lions on Sunday, Sept. 22. The Bronzed Busts to be displayed include: • Bert Bell • Sonny Jurgensen • Norm Van Brocklin • Chuck Bednarik • Tommy McDonald • Steve Van Buren • Bob Brown • Earl “Greasy” Neale • Reggie White • Brian Dawkins • Pete Pihos • Alex Wojciechowicz • Bill Hewitt • Jim Ringo More information on the Eagles Fantennial can be found at https://fanpages.philadelphiaeagles.com/nfl100.html. September 16-19, 2020 A once-in-every- other-lifetime celebration to kick off the NFL’s next century in the city where the league was born. -

Hrizonhhighways February • 1951

HRIZONHHIGHWAYS FEBRUARY • 1951 . THIRTY-FIVE CENTS , l /jJI I\fj Spring has a good press. The poets make much ado about birds, bees, flowers and the sprightliness of the season. They neglect such mundane subjects as spring house cleaning and overlook the melancholy fact that armies with evil intentions march when the snow melts. We hope our only concern is with flowers, bees and birds and things like that. As for spring house cleaning, just open the doors and let the house air out. Why joust with vacuum cleaners and mops when spring beckons? Spring does a good job of beckoning in the desert land. It is our pleasure to show you some panoramas of the desert and desert plateau country when nature's fashion calls for spring dress. We wish we could promise the most colorful spring ever but the effiorescence of spring depends on the rainfall. We have had a darned dry "dry spell" hereabouts, broken only by a good rain in late January. If the rains keep on, then we can predict a real pretty March, April and May, but who the heck is going to be silly enough to try to tell whether it'll rain. Anyway, we'll promise you grand weather. An Arizona spring can't be beat. The weather had better be perfect! Sometime this month a group of wonderfully agile and extremely well paid young men who answer to the roll call of the Cleveland Indians, and another group of even more agile and even better paid young men who form the New York Yankees baseball team arrive in Tucson and Phoenix for spring training, the latter to get ready to defend the World's Championship, the former to try to bring it to Cleveland. -

Football Hall Selects Another Marine

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 22, No. 5 (2000) Football Hall selects another Marine By John Gunn Camp Lejeune Globe/ 5-5 On the football field, he was a hawk, not a dove. As a result, former Marine Bob Dove of Notre Dame and NFL fame was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame. He is at least the 45th former Marine so honored. The hall's Honor Committee, which reviews accomplishments of players of more than 50 years ago, selected Dove, a three-year starter at end for the Fighting Irish from 1940-42, a two-time All-American and winner of the Knute Rockne Trophy in 1942. "It had been over 50 years. I almost forgot about it," Dove said. (Similar efforts have been unsuccessful to honor back George Franck, a Minnesota All-American who was third in the 1940 Heisman Trophy voting and a Marine aviator in the South Pacific during WW II.) THIRTEEN OTHER PLAYERS and two coaches whose selections were announced April 25 at a South Bend, Ind., news conference will be inducted into the hall at a Dec. 12 banquet in New York and formally enshrined at South Bend in August 2001. Dove, who played nine seasons with the Chicago Rockets, Chicago Cardinals and Detroit Lions, also starred for the El Toro Flying Marines in 1944 and '45 -- the "Boys of Autumn" and strongest Leatherneck teams ever fielded. The '44 team won eight, lost one and was ranked 16th in The Associated Press poll even though the base was barely a year and a half old. -

Vol. 10, No. 2 (1988) JACK FERRANTE: EAGLES GREAT

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 10, No. 2 (1988) JACK FERRANTE: EAGLES GREAT By Richard Pagano Reprinted from Town Talk, 1/6/88 In 1933, Bert Bell and Lud Wray formed a syndicate to purchase the Frankford Yellowjackets' N.F.L. franchise. On July 9 they bought the team for $2,500. Bell named the team "The Eagles", in honor of the eagle, which was the symbol of the National Recovery Administration of the New Deal. The Eagles' first coach was Wray and Bell became Philadelphia's first general managers. In 1936, Bert Bell purchased sole ownership of the team for $4,000. He also disposed of Wray as head coach, and took on the job himself. From 1933 until 1941, the Philadelphia Eagles never had a winning season. Even Davey O'Brien, the All-American quarterback signed in 1939, could not the Eagles out of the Eastern Division cellar. Bert Bell finally sold the Eagles in 1941. He sold half the franchise to Alexis Thompson of New York. Before the season, Rooney and Bell swapped Thompson their Philadelphia franchise for his Pittsburgh franchise. The new owner hired Earle "Greasy" Neale to coach the team. In 1944, the Eagles really started winning. They finished with a record of 7-1-2 and ended the season in second place in the Eastern Division. From 1944 until 1950, the Philadelphia Eagles enjoyed their most successful years in the history of the franchise. They finished second in the Eastern Division three times and also won the Eastern Division championship three times. The Eagles played in three consecutive N.F.L.