Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download South Park Drawing Guide : Learn To

SOUTH PARK DRAWING GUIDE : LEARN TO DRAW KENNY, CARTMAN, KYLE, STAN, BUTTERS AND FRIENDS! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Go with the Flo Books | 100 pages | 04 Dec 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781519695369 | English | none South Park Drawing Guide : Learn to Draw Kenny, Cartman, Kyle, Stan, Butters and Friends! PDF Book Meanwhile, Butters is sent to a special camp where they "Pray the Gay Away. See more ideas about south park, south park anime, south park fanart. After a conversation with God, Kenny gets brought back to life and put on life support. This might be why there seems to be an air of detachment from Stan sometimes, either as a way to shake off hurt feelings or anger and frustration boiling from below the surface. I was asked if I could make Cartoon Animals. Whittle his Armor down and block his high-powered attacks and you'll bring him down, faster if you defeat Sparky, which lowers his defense more, which is recommended. Butters ends up Even Butters joins in when his T. Both will use their boss-specific skill on their first turn. Garrison wielding an ever-lively Mr. Collection: Merry Christmas. It is the main protagonists in South Park cartoon movie. Climb up the ladder and shoot the valve. Donovan tells them that he's in the backyard. He can later be found on the top ramp and still be aggressive, but cannot be battled. His best friend is Kyle Brovlovski. Privacy Policy.. To most people, South Park will forever remain one of the quirkiest and wittiest animated sitcoms created by two guys who can't draw well if their lives depended on it. -

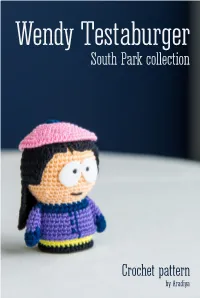

Eng Tutorial Wendy

Wendy Testaburger South Park collection Crochet pattern by Aradiya 1 Instruments and materials 1.25 and 2.00 mm hooks Purple, navy blue, pink, flesh-colored, yellow and black yarn Sewing needle Stung material A piece of white felt Image 1 Wendy Testaburger - character of the popular cartoon “South Park”. To create a toy with a height of 7.5 cm you must crochet with single yarn using a 2.00 mm hook. The arms, the hair and the hat are crocheted with single yarn using a 1.25 mm hook. The stung material used in this toy is polyester wadding. The piece of felt must be 1.5 mm thick. This pattern is for personal use only. Sharing information from this pattern is prohibited. If you publish photos of the toys that are crocheted following this pattern, it is better to mention the author of the pattern. You can also use hashtag #AradiyaToys at Twitter and Instagram to share your toy and see other toys that are created following AradiyaToys’ patterns. 2 Abbreviations Ch - chain Sl - slip stitch Sc - single crochet Dc - double crochet HDc - half double crochet INC - increase INVDEC - invisible decrease BLO - back loops only FLO - front loops only Tip 1 The toy must be All amigurumi toys crocheted with tight are crocheted with tight stitches. Avoid stitches, to be sure that small holes when there won't be any holes stretching crochet through which stung fabric, if there are material can some tiny holes, be seen. use a smaller size hook. To avoid seams, all details are crocheted in a spiral without slip stitch and lifting loops. -

Cartman Will Not Be Silenced in an All-New Episode of 'South Park' Premiering on Wednesday, November 11 at 10:00 P.M

Cartman Will Not Be Silenced in an All-New Episode of 'South Park' Premiering on Wednesday, November 11 at 10:00 p.m. on COMEDY CENTRAL(R) NEW YORK, Nov 09, 2009 -- Cartman has a daily forum for his agenda when he is chosen to do the morning announcements at school in an all-new "South Park" titled, "Dances with Smurfs," premiering on Wednesday, November 11 at 10:00 p.m. on COMEDY CENTRAL. Eric Cartman seizes the opportunity to become the voice of change at the school when he takes over the morning announcements. His target is South Park Elementary's Student Body President, Wendy Testaburger. Cartman is asking the tough questions and gaining followers. Launched in 1997, "South Park," now in its 13th season, remains the highest-rated series on COMEDY CENTRAL. "South Park" repeats Wednesdays at 12:00 a.m., Thursdays at 10:00 p.m. and 12:00 a.m. and Sundays at 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m. Co-creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone are executive producers, along with Anne Garefino, of the Emmy® and Peabody® Award-winning "South Park." Frank C. Agnone II is the supervising producer. Eric Stough, Adrien Beard, Bruce Howell, Vernon Chatman and Erica Rivinoja are producers. "South Park's" Web site is www.southparkstudios.com. COMEDY CENTRAL, the only all-comedy network, currently is seen in more than 95 million homes nationwide. COMEDY CENTRAL is owned by, and is a registered trademark of, Comedy Partners, a wholly-owned division of Viacom Inc.'s (NYSE: VIA and VIA.B) MTV Networks. -

Gruda Mpp Me Assis.Pdf

MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK ASSIS 2011 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo Trabalho financiado pela CAPES ASSIS 2011 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca da F.C.L. – Assis – UNESP Gruda, Mateus Pranzetti Paul G885d O discurso politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park / Mateus Pranzetti Paul Gruda. Assis, 2011 127 f. : il. Dissertação de Mestrado – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – Universidade Estadual Paulista Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo. 1. Humor, sátira, etc. 2. Desenho animado. 3. Psicologia social. I. Título. CDD 158.2 741.58 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM “SOUTH PARK” Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Data da aprovação: 16/06/2011 COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA Presidente: PROF. DR. JOSÉ STERZA JUSTO – UNESP/Assis Membros: PROF. DR. RAFAEL SIQUEIRA DE GUIMARÃES – UNICENTRO/ Irati PROF. DR. NELSON PEDRO DA SILVA – UNESP/Assis GRUDA, M. P. P. O discurso do humor politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park. -

409 - Flutschfinger on Tour

planearium.de 409 - Flutschfinger On Tour Mitgeschrieben von: Jesus (Lars Wassermann) Stan Marsh Kyle Broflovski Eric Cartman Kenny McCormick Wendy Testaburger Butters Stotch Timmy Randy, Sharon und Shelley Marsh Mr. Mackey Liane Cartman Kind am Klavier (Schröder) gestresster Manager vom Einkaufszentrum Alter und Junger Sicherheitswachmann Bebe und die anderen Mädchen Aufnahmeproduzent diverse Leute, die im Markt einkaufen Kleines Mädchen [Eine große Stadt, es ist Nacht. Scheinwerferlicht durchdringt die Luft. Eine riesige Menschenmenge hat sich vor einem großen Gebäude versammelt.] Ansager: Stellar Productions präsentiert DIE Boygroup des Jahrzehnts! [Frauen schreien, springen und kreischen. Einige halten Schilder hoch, wo draufsteht: "FINGERBANG RULES", "FINGER BANG", "WE LOVE FINGER BANG" und "FINGER BANG 4EVER".] Hier sind Flutschfinger, live aus dem Madison Square Garden! [Das Innere wird mit einer jubelnden Menschenmenge gezeigt. Ein Soundeffekt ist zu hören und Scheinwerfer flackern über die Bühne. Ein Feuerwerk leitet die Musik ein und die vertrauten Silhouetten von vier Jungs sind auf der Bühne zu sehen. Ein paar Frauen werden ohnmächtig.] Flutschfinger: [Die Lichter werden auf die Jungs gerichtet und es sind Kyle, Stan, Cartman und Kenny, die weiße Outfits anhaben. Auch ihre Mützen sind allesamt weiß. Kyle trägt zusätzlich ein grünes, Stan ein blaues Shirt. Kenny hat ein oranges Visir über seine weiße Kapuze gezogen. Alle tragen Headsets.] Fingerpop! [jeder dreht sich zur Menge hin und stoppt] Pop-pop! Fingerpop-pop! [sie drehen sich zu ihrer ursprünglichen Position zurück] Pop-pop-pop! [alle machen einen Schritt nach vorn und tanzen dann nach ihrem Song] Ich mach den Fingerpop-pop, da stehst du voll drauf Mädchen, das ist was du brauchst, ich hör nicht auf. -

South Park's Ambiguoues Satiric Expression

SOUTH PARK'S AMBIGUOUES SATIRIC EXPRESSION MICHAEL ADRIAAN VITTALI This Master Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at the University of Agder and is therefore approved as a part of this education. However, this does not imply that the University answers for the methods that are used or the conclusions that are drawn. University of Agder, May 2010 Faculty of Humanities and Education Department of Foreign Languages and Translation Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my advisor Michael J. Prince. He shares my fascination with South Park, and as such he has been a great help. Thank you pointing me in the right direction and giving me great advice and encouragement. Thanks for letting me write about one of my favorite shows. Second, thanks must also be given to “The Mexican” for showing me a lot of excess fat which needed to be trimmed in my thesis. Thanks for the “editing”. Lastly, I would like to thank my girlfriend Maren, who stuck by me while I analyzed South Park against her will every time it came on TV. She has also been a great help in showing me the usefulness of the comma. Table of Contents Introduction and Background........................................................….1 Chapter 1: The Inner Workings of South Park ………………........ .6 The Animation ………………………………………………..….....6 Satire and the Carnivalesque Nature of South Park …………..…. 11 Chapter 2: What’s So Funny? ……………………………….….... 20 South Park in Action …………………………………………..… 21 Chapter 3: South Park and the War on Terror ………………...… 26 Chapter 4: Voting and the Rights of Cows ………………….…... 37 Summing Up: South Park’s Ambiguous Satire ……..……….…. -

DAY WENDY Stan, You Know It's Almost Valentines Day... STAN I

ACT I INT. CLASSROOM - DAY WENDY Stan, you know it's almost Valentines day... STAN I know. WENDY Maybe we should go on a cruise or something. STAN I can't afford a cruise, dude! WENDY (Sweet) I know, but we could make a little boat out of cardboard, and pretend it's a cruise! Cartman hears this and just starts laughing his ass off. STAN Shut up Cartman! CARTMAN HOO, HOO! HOH THAT IS SO LAME HA HA HOO HOO! WENDY And then we could dress up in little costumes and pretend like we're getting married. Cartman hears this and just starts laughing his ass off again. CARTMAN Stop, seriously. You're killing me over here. Principal Victoria steps in front of the class. PRINCIPAL VICTORIA Children, I have some difficult news for you... Mr. Garrison won't be teaching for a while. He has to have surgery. The kids all cheer. PRINCIPAL VICTORIA (CONT'D) So you're going to have a substitute teacher. And I want you to show the substitute the SAME respect you show for Mr. Garrison... Yes, little boy? KYLE (Flatly) We don't have respect for Mr. Garrison. PRINCIPAL VICTORIA Oh. The kids just sit there. PRINCIPAL VICTORIA (CONT'D) Anyhoo, I want you all to meet your new substitute... Ms. Ellen. MS. ELLEN walks in, she is beautiful and classy. MS. ELLEN Hello, children. STAN AND KYLE Woa... CARTMAN Wow, she's PRETTY!! KENNY Mph rmph rm rmph!! STAN You can say that again! KENNY Mph rmph rm rmph!! PRINCIPAL VICTORIA Good Luck, Ms. -

Practice Midterm Examination

Math364 (Spring 2019): Practice Midterm 1 Principles of Optimization (Spring 2019) Practice Midterm Examination Name: WSU ID: • There are six problems in this exam. • The total points (given in parentheses) add to 105. You will be graded for 100. • Space given here should be sufficient to do all necessary work, but in case you use any extra sheets of paper for rough work, write your name on each such sheet, and attach all such sheets to this exam before submitting. • Time is precious|try to first finish problems that you are sure of. Good luck! 1. (18) Suppose we have obtained the following tableau for a minimization LP. z x1 x2 x3 x4 x5 x6 rhs ∗ 1 c1 c2 0 c3 c4 c5 z 0 3 a1 1 0 a2 a3 1 0 -1 -2 0 a4 -1 a5 b 0 a6 -4 0 0 -3 a7 3 ∗ State conditions on a1; : : : ; a7; c1; : : : ; c5; b and z required to make the following state- ments true. (a) The current solution is optimal, and there are alternative optimal basic feasible solutions. (b) The LP is unbounded. 2. (18) Solve the following LP using tableau simplex method. max z = 2x1 − x2 + 2x3 s.t. 3x1 + 2x2 + x3 ≤ 6 − 4x2 + 2x3 ≤ 2 x1; x2; x3 ≥ 0 3. (18) Solve the following LP graphically. max z = 3x1 − 2x2 s.t. 2x1 + x2 ≤ 6 2x1 + 5x2 ≥ 6 −2x1 + 3x2 ≤ 10 Math364 (Spring 2019): Practice Midterm 2 4. (18) Kyle just solved an LP with two constraints. Cartman wants to solve the same LP, but Kyle would not give it to him. -

THE TUFTS DAILY Est

Where You Read It First Sunny 52/35 THE TUFTS DAILY Est. 1980 VOLUME LX, NUMBER 31 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 22, 2010 TUFTSDAILY.COM Somerville named one of 100 top communities for youth BY SMRITI CHOUDHURY Somerville Superintendent of Daily Staff Writer Schools Tony Pierantozzi. America’s Promise Alliance, Somerville last month a nation-wide partnership nabbed a top spot in a nation- organization of business- wide competition seeking es and non-profits aimed the best neighborhoods for at improving youths’ lives, youth. spearheaded the competi- The 100 Best Communities tion. The group received for Young People list, spon- more than 350 community sored by financial institution nominations from across the ING, is designed to recognize nation. The winning commu- communities that concen- nities demonstrated efforts to trate on the future of youth improve educational oppor- by decreasing high school tunities for youth and imple- dropout rates and prepar- mented initiatives focused on ing youth for college and the youth health care and civic workforce. engagement. This marks the second time Somerville spokesperson that Somerville came out as Jaclyn Rossetti said the city’s one of the nation’s “100 Best.” second recognition in the The city also earned the dis- tinction in 2008, according to see SOMERVILLE, page 3 DILYS ONG/TUFTS DAILY The MBTA is increasing its presence at a number of trouble stations, including Kendall and Central Square on the Red Line. Above, the Red Line’s Harvard Square station. MBTA cracks down on fare evaders, steps up enforcement across system BY LAINA PIERA can be at any gate at any time.” “While Davis is not high on Contributing Writer Fare evasion most often our list, problem stations in occurs when individuals follow the area include Kendall and The Massachusetts Bay other riders through the turn- Central,” Lenehan said. -

Perpustakaan.Uns.Ac.Id Digilib.Uns.Ac.Id Commit to User 44

perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id BAB II DESKRIPSI OBYEK PENELITIAN A. Deskripsi Umum 1. Serial Animasi South Park Serial animasi South Park merupakan salah satu sitcom yang berasal dari Amerika. Sitcom merupakan singkatan dari situation comedy yang berarti salah satu jenis komedi yang memiliki ciri-ciri berupa penggambaran lingkungan pada umumnya, seperti rumah atau tempat kerja, dengan dialog berupa humor. Pencipta serial kartun ini adalah dua orang laki-laki bernama Matt Stone dan Trey Parker yang berasal dari almamater yang sama, yaitu University of Colorado at Boulder. Walaupun visualisasi serial ini berupa animasi yang berwarna-warni, namun audien yang ditargetkan bukan anak-anak, melainkan audien dewasa karena mengandung konten humor untuk dewasa. Matt Stone dan Trey Parker mengawali karir dalam bidang film pada tahun 1989 dengan cara berkolaborasi. Pada tahun 1992, muncul film pendek bertema komedi berjudul Jesus Vs. Frosty, kemudian diikuti munculnya karya serupa yang berjudul Jesus Vs. Santa pada tahun 1995, yang mana keduanya merupakan karya mereka berdua sekaligus sebagai cikal bakal munculnya South Park. Sejalan dengan karir pada bidang penyiaran, Comedy Central melirik karya-karya mereka lalu menyewa mereka untuk mengembangkannya menjadi serial, dengan penayangan commit to user 44 perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id perdana serial animasi South Park pada tanggal 13 Agustus 1997. Comedy Central adalah distributor program televisi asal Amerika, khususnya bidang komedi, dengan berbasis televisi kabel yang merupakan bagian dari MTV Networks Entertainment Group. Serial animasi South Park dirilis melalui urutan musim (season) yang mana dari masing-masing season tersebut rata-rata terdiri dari 14 episode, sedangkan masing-masing episode memiliki durasi rata-rata sekitar 22 menit. -

'South Park' Çizgi

T.C. FIRAT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ İLETİŞİM BİLİMLERİ ANA BİLİM DALI ‘SOUTH PARK’ ÇİZGİ DİZİSİNDEKİ TOPLUMSAL NORM MESAJLARININ GÖSTERGEBİLİMSEL ANALİZİ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN HAZIRLAYAN Yrd. Doç. Dr. Işıl HORZUM Songül DEMİR ELAZIĞ-2014 T.C. FIRAT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ İLETİŞİM BİLİMLERİ ANABİLİM DALI ‘SOUTH PARK’ ÇİZGİ DİZİSİNDEKİ TOPLUMSAL NORM MESAJLARININ GÖSTERGEBİLİMSEL ANALİZİ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN HAZIRLAYAN Yrd. Doç. Dr. Işıl HORZUM Songül DEMİR Jürimiz,……………… tarihinde yapılan yüksek lisans tezini oy birliği / oy çokluğu ile başarılı saymıştır. Jüri Üyeleri: 1. 2. 3. F.Ü. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Yönetim Kurulu’nun …………. Tarih ve ………… sayılı kararıyla bu tezin kabulü onaylanmıştır. Prof. Dr. Zakir KIZMAZ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürü II ÖZET Yüksek Lisans Tezi ‘South Park’ Çizgi Dizisindeki Toplumsal Norm Mesajlarının Göstergebilimsel Analizi Songül DEMİR Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü İletişim Bilimleri Anabilim Dalı Elazığ-2014, Sayfa: XII + 123 Bir toplumda insanların belli olaylar karşısında nasıl davranmaları gerektiğini belirleyen, onları belirli şekilde davranmaya zorlayan kurallara sosyal norm denir. Toplumlar bunu, siyaset ve medyayla ağırlıklı olarak yapar. Toplumu sürükleyen bu kurallar bütünü zamanla insanların tektipleşmesine sebebiyet verir. Bunu anlamak ya da bu gerçeğin farkında olmak için bu çizgi diziyi analiz etmek, bir sonraki sosyolojik çalışmalara katkı sağlamanın yanı sıra South Park isimli çizgi dizisi üzerine yazılmış metinlerin dışında, dizi üzerine yapılacak çalışma olarak tek olacağından, bu alandaki diğer araştırmalara da öncülük edecek olması açısından önemlidir. Araştırma kapsamında South Park çizgi dizisinin yanı sıra toplumsal normların insanla etkileşimi ve popüler kültür emperyalizmi ele alınmış olacaktır. İletişimin en etkili rollerinden biri olan görüntü sanatını sosyolojiyle kaynaştıran bu çizgi dizi, bizlere toplumsal şekillenme ve yönlenmeyi gösterecektir. -

South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut

South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut By Trey Parker Matt Stone & Pam Brady Eighth Draft January 21, 1999 FADE IN: Very happy, Disneyesque MUSIC swirls in. PAN DOWN from a pretty blue sky, to a small quaint town nestled in the hills. A wooden sign tells us this is South Park. EXT. SOUTH PARK AVENUE - DAY Birds fly into the air, TOWNSPEOPLE smile to each other as they walk by. It is a scene reminiscent of, if not directly ripped off from, the opening number of 'Beauty and the Beast'. A little eight year old boy walks happily down the street. He is STAN MARSH, a noble looking boy with piercing blue eyes and a strong chin. As he walks, he sings a happy song. STAN I'm going to the movies To see the brighter side of life! I'm going to the movie Everything's gonna be alright! Forget all my troubles Put my own life on hold Let a studio tell me how I should view the world Where everything works out I love it that way I'm going to the movies The movies today! Stan merrily walks up to a crappy looking house. INT. BEDROOM - MORNING We are in a young boy's bedroom, just as his alarm clock goes off. BRRRRRTTT!!! RADIO ANNOUNCER Good morning South Park! It's five-thirty a.m. on Sunday!! Time to feed the horses and water the cows!! From the back, we see the blond haired kid sit up from his bed. He stretches, and then walks over to his closet.