Nest Architecture and Avian Systematics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds Along Lehi's Trail

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 15 Number 2 Article 10 7-31-2006 Birds Along Lehi's Trail Stephen L. Carr Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Carr, Stephen L. (2006) "Birds Along Lehi's Trail," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 15 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol15/iss2/10 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Birds Along Lehi’s Trail Author(s) Stephen L. Carr Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 15/2 (2006): 84–93, 125–26. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract When Carr traveled to the Middle East, he observed the local birds. In this article, he suggests the possi- bility that the Book of Mormon prophet Lehi and his family relied on birds for food and for locating water. Carr discusses the various birds that Lehi’s family may have seen on their journey and the Mosaic law per- taining to those birds. Birds - ALOnG LEHI’S TRAIL stephen l. cARR 84 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 2, 2006 PHOTOGRAPHy By RICHARD wELLINGTOn he opportunity to observe The King James translators apparently ex- birds of the Middle East came to perienced difficulty in knowing exactly which me in September 2000 as a member Middle Eastern birds were meant in certain pas- Tof a small group of Latter-day Saints1 traveling in sages of the Hebrew Bible. -

The First Mangrove Swallow Recorded in the United States

The First Mangrove Swallow recorded in the United States INTRODUCTION tem with a one-lane unsurfaced road on top, Paul W. Sykes, Jr. The Space Coast Birding and Wildlife Festival make up the wetland part of the facility (Fig- USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center was held at Titusville, Brevard County, ures 1 and 2). The impoundments comprise a Florida on 13–17 November 2002. During total of 57 hectares (140 acres), are kept Warnell School of Forest Resources the birding competition on the last day of the flooded much of the time, and present an festival, the Canadian Team reported seeing open expanse of shallow water in an other- The University of Georgia several distant swallows at Brevard County’s wise xeric landscape. Patches of emergent South Central Regional Wastewater Treat- freshwater vegetation form mosaics across Athens, Georgia 30602-2152 ment Facility known as Viera Wetlands. open water within each impoundment and in They thought these were either Cliff the shallows along the dikes. A few trees and (email: [email protected]) (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) or Cave (P. fulva) aquatic shrubs are scattered across these wet- Swallows. lands. Following his participation at the festival, At about 0830 EST on the 18th, Gardler Gardler looked for the swallows on 18 stopped on the southmost dike of Cell 1 Lyn S. Atherton November. The man-made Viera Wetlands (Figure 2) to observe swallows foraging low are well known for waders, waterfowl, rap- over the water and flying into the strong 1100 Pinellas Bayway, I-3 tors, shorebirds, and open-country passer- north-to-northwest wind. -

Migratory Birds of Ladakh a Brief Long Distance Continental Migration

WORLD'S MIGRATORY BIRDS DAY 08 MAY, 2021 B R O W N H E A D E D G U L L MIGRATORY BIRDS OF LADAKH A BRIEF LONG DISTANCE CONTINENTAL MIGRATION the Arctic Ocean and the Indian Ocean, and comprises several migration routes of waterbirds. It also touches “West Asian- East African Flyway”. Presence of number of high-altitude wetlands (>2500 m amsl altitude) with thin human population makes Ladakh a suitable habitat for migration and breeding of continental birds, including wetlands of very big size (e.g., Pangong Tso, Tso Moriri, Tso Kar, etc.). C O M M O N S A N D P I P E R Ladakh provides a vast habitat for the water birds through its complex Ladakh landscape has significance network of wetlands including two being located at the conjunction of most important wetlands (Tso Moriri, four zoogeographic zones of the world Tso Kar) which have been designated (Palearctic, Oriental, Sino-Japanese and as Ramsar sites. Sahara-Arabian). In India, Ladakh landscape falls in Trans-Himalayan Nearly 89 bird species (long distance biogeographic zone and two provinces migrants) either breed or roost in (Ladakh Mountains, 1A) and (Tibetan Ladakh, and most of them (59) are Plateau, 1B). “Summer Migrants”, those have their breeding grounds here. Trans-Himalayan Ladakh is an integral part of the "Central Asian Flyway" of migratory birds which a large part of the globe (Asia and Europe) between Ladakh also hosts 25 bird species, during their migration along the Central Asian Flyway, as “Passage Migrants” which roost in the region. -

Wings Over Alaska Checklist

Blue-winged Teal GREBES a Chinese Pond-Heron Semipalmated Plover c Temminck's Stint c Western Gull c Cinnamon Teal r Pied-billed Grebe c Cattle Egret c Little Ringed Plover r Long-toed Stint Glacuous-winged Gull Northern Shoveler Horned Grebe a Green Heron Killdeer Least Sandpiper Glaucous Gull Northern Pintail Red-necked Grebe Black-crowned r White-rumped Sandpiper a Great Black-backed Gull a r Eurasian Dotterel c Garganey a Eared Grebe Night-Heron OYSTERCATCHER Baird's Sandpiper Sabine's Gull c Baikal Teal Western Grebe VULTURES, HAWKS, Black Oystercatcher Pectoral Sandpiper Black-legged Kittiwake FALCONS Green-winged Teal [Clark's Grebe] STILTS, AVOCETS Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Red-legged Kittiwake c Turkey Vulture Canvasback a Black-winged Stilt a Purple Sandpiper Ross' Gull Wings Over Alaska ALBATROSSES Osprey Redhead a Shy Albatross a American Avocet Rock Sandpiper Ivory Gull Bald Eagle c Common Pochard Laysan Albatross SANDPIPERS Dunlin r Caspian Tern c White-tailed Eagle Ring-necked Duck Black-footed Albatross r Common Greenshank c Curlew Sandpiper r Common Tern Alaska Bird Checklist c Steller's Sea-Eagle r Tufted Duck Short-tailed Albatross Greater Yellowlegs Stilt Sandpiper Arctic Tern for (your name) Northern Harrier Greater Scaup Lesser Yellowlegs c Spoonbill Sandpiper Aleutian Tern PETRELS, SHEARWATERS [Gray Frog-Hawk] Lesser Scaup a Marsh Sandpiper c Broad-billed Sandpiper a Sooty Tern Northern Fulmar Sharp-shinned Hawk Steller's Eider c Spotted Redshank Buff-breasted Sandpiper c White-winged Tern Mottled Petrel [Cooper's -

Kanha Survey Bird ID Guide (Pdf; 11

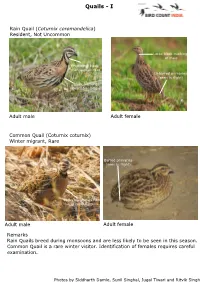

Quails - I Rain Quail (Coturnix coromandelica) Resident, Not Uncommon Lacks black markings of male Prominent black markings on face Unbarred primaries (seen in flight) Black markings (variable) below Adult male Adult female Common Quail (Coturnix coturnix) Winter migrant, Rare Barred primaries (seen in flight) Lacks black markings of male Rain Adult male Adult female Remarks Rain Quails breed during monsoons and are less likely to be seen in this season. Common Quail is a rare winter visitor. Identification of females requires careful examination. Photos by Siddharth Damle, Sunil Singhal, Jugal Tiwari and Ritvik Singh Quails - II Jungle Bush-Quail (Perdicula asiatica) Resident, Common Rufous and white supercilium Rufous & white Brown ear-coverts supercilium and Strongly marked brown ear-coverts above Rock Bush-Quail (Perdicula argoondah) Resident, Not Uncommon Plain head without Lacks brown ear-coverts markings Little or no streaks and spots above Remarks Jungle is typically more common than Rock in Central India. Photos by Nikhil Devasar, Aseem Kumar Kothiala, Siddharth Damle and Savithri Singh Crested (Oriental) Honey Buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) Resident, Common Adult plumages: male (left), female (right) 'Pigeon-headed', weak bill Weak bill Long neck Long, slender Variable streaks and and weak markings below build Adults in flight: dark morph male (left), female (right) Confusable with Less broad, rectangular Crested Hawk-Eagle wings Rectangular wings, Confusable with Crested Serpent not broad Eagle Long neck Juvenile plumages Confusable -

The First Record of Common House-Martin (Delichon Urbicum) for British Columbia. by Rick Toochin, Peter Hamel, Margo Hearne and Martin Williams

The First Record of Common House-Martin (Delichon urbicum) for British Columbia. By Rick Toochin, Peter Hamel, Margo Hearne and Martin Williams. Introduction and Distribution The Common House-Martin (Delichon urbicum) is a small passerine found in the Old World from Europe and Asia. There are 2 subspecies and most size differences between north and southern populations are clinal (Turner and Rose 1989). In Europe, the nominate subspecies (D. u. urbicum) is found breeding from Great Britain, to Russia, also in North Africa and across the Mediterranean Sea to Turkey and Israel and further east to central Asia (Mullarney and Zetterstrom 2009). This subspecies of the Common House-Martin winters throughout west and southeast Africa (Mullarney and Zetterstrom 2009). In Far East Asia, the subspecies (D. u. lagopodum) of Common-House Martin is a widespread breeding species from the Yenisei to North-east China, North-east Russia, Yakutia, Chukotka, north Koryakia coast and possibly in Kamchatka (Brazil 2009). The Common House-Martin is a rare migrant in Japan and Korea (Brazil 2009). This subspecies does winter in small numbers in South Eastern China, but the bulk of the population winters in Southeast Asia (Brazil 2009). In North America, the Common House-Martin is an accidental to casual vagrant (Dunn and Alderfer 2011). In Alaska, there is one specimen record of the Common House-Martin which belongs to the Asian subspecies (D. u. lagopodum), which is assumed to be the rest of the observations in Alaska, and this species is classified as casual with scattered records from Nome, St. Paul Island, Gambell, Buldir Island, St. -

Discovering the Migration and Non-Breeding Areas of Sand Martins and House Martins Breeding in the Pannonian Basin (Central-Eastern Europe)

Journal of Avian Biology 48: 114–122, 2017 doi: 10.1111/jav.01339 © 2016 The Authors. This is an Online Open article Guest Editor: Anders Hedenström. Editor-in-Chief: Jan-Åke Nilsson. Accepted 15 November 2016 Discovering the migration and non-breeding areas of sand martins and house martins breeding in the Pannonian basin (central-eastern Europe) Tibor Szép, Felix Liechti, Károly Nagy, Zsolt Nagy and Steffen Hahn T. Szép, Inst. of Environmental Science, Univ. of Nyíregyháza, Nyíregyháza, Hungary. – F. Liechti ([email protected]) and S. Hahn, Dept of Bird Migration, Swiss Ornithological Inst., Sempach, Switzerland. – K. Nagy and Z. Nagy, MME/BirdLife, Budapest, Hungary. The central-eastern European populations of sand martin and house martin have declined in the last decades. The driv- ers for this decline cannot be identified as long as the whereabouts of these long distance migrants remain unknown outside the breeding season. Ringing recoveries of sand martins from central-eastern Europe are widely scattered in the Mediterranean basin and in Africa, suggesting various migration routes and a broad non-breeding range. The European populations of house martins are assumed to be longitudinally separated across their non-breeding range and thus narrow population-specific non-breeding areas are expected. By using geolocators, we identified for the first time, the migration routes and non-breeding areas of sand martins (n 4) and house martins (n 5) breeding in central-eastern Europe. In autumn, the Carpathian Bend and northern parts of the Balkan Peninsula serve as important pre-migration areas for both species. All individuals crossed the Mediterranean Sea from Greece to Libya. -

Avifaunal Baseline Assessment of Wadi Al-Quff Protected Area and Its Vicinity, Hebron, Palestine

58 Jordan Journal of Natural History Avifaunal baseline assessment of Wadi Al-Quff Protected Area and its Vicinity, Hebron, Palestine Anton Khalilieh Palestine Museum of Natural History, Bethlehem University, Bethlehem, Palestine Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Birds of Wadi Al-Quff protected area (WQPA) were studied during the spring season of 2014. A total of 89 species of birds were recorded. Thirty species were found to breed within the protected area (24 resident and 6 summer breeders), while the others were migratory. Three species of raptors (Long legged Buzzard, Short-toed Eagle and the Hobby) were found to breed within man-made afforested area, nesting on pine and cypress trees. Within the Mediterranean woodland patches, several bird species were found nesting such as Cretzschmar's Bunting, Syrian Woodpecker, Sardinian Warbler and Wren. Thirteen species of migratory soaring birds were recorded passing over WQPA, two of them (Egyptian Vulture and Palled Harrier) are listed by the IUCN as endangered and near threatened, respectively. In addition, several migratory soaring birds were found to use the site as a roosting area, mainly at pine trees. Key words: Birds; Palestine; Endangered species. INTRODUCTION The land of historical Palestine (now Israel, West bank and Gaza) is privileged with a unique location between three continents; Europe, Asia, and Africa, and a diversity of climatic regions (Soto-Berelov et al., 2012). For this reason and despite its small area, a total of 540 species of bird were recorded (Perlman & Meyrav, 2009). In addition, Palestine is at the second most important migratory flyway in the world. Diverse species of resident, summer visitor breeders, winter visitor, passage migrants and accidental visitors were recorded (Shirihi, 1996). -

The 55 Species of Larger Mammal Known to Be Present in The

Birds of Lolldaiga Hills Ranch¹ Order and scientific name² Common name² Threat3 Comments Struthionidae Ostrich Struthio camelus Common ostrich LC Both S. c. camelus (LC) and S. c. molybdophanes (Somali ostrich) (VU) present. These considered species by some authorities. Numididae Guineafowl Numida meleagris Helmeted guineafowl LC Acryllium vulturinum Vulturine guineafowl LC Phasianidae Stone partridge, francolins, spurfowl, quails Ptilopachus petrosus Stone partridge LC Francolinus shelleyi Shelley’s francolin LC Francolinus sephaena Crested francolin LC Francolinus squamatus Scaly francolin LC Francolinus hildebrandti Hildebrandt’s francolin LC Francolinus leucoscepus Yellow-necked spurfowl LC Coturnix coturnix Common quail LC Coturnix delegorguei Harlequin quail LC Anatidae Ducks, geese Dendrocygna viduata White-faced whistling duck LC Sarkidiornis melanotos Knob-billed duck LC Alopochen aegyptiaca Egyptian goose LC Anas strepera Gadwall LC Anas sparsa African black duck LC Anas undulata Yellow-billed duck LC 1 Order and scientific name² Common name² Threat3 Comments Anas clypeata Northern shoveler LC Anas erythrorhyncha Red-billed teal LC Anas acuta Northern pintail LC Anas querquedula Garganey LC Anas crecca Eurasian teal LC Anas hottentota Hottentot teal LC Netta erythrophthalma Southern pochard LC Oxyura maccoa Maccoa duck NT Podicipedidae Grebes Tachybaptus ruficollis20 Little grebe LC Ciconiidae Storks Mycteria ibis Yellow-billed stork LC Anastomus lamelligerus African open-billed stork LC Ciconia nigra Black stork LC Ciconia abdimii -

Page 1 of 4 BIRDLIST Danube Delta – Dobrudja Spring Tour

BIRDLIST Page 1 of 4 Danube Delta – Dobrudja Spring Tour A list of possible birds on this tour follows. To give some idea of the probability of a particular species being seen at least once during this tour, species are marked as follows: No star signifies a high probability 1 star (*) signifies a moderate probability 2 star (**) signifies a low probability Common Quail Coturnix coturnix Grey Partidge Perdix perdix* Greylag Goose Anser anser Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea* Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope Gadwall Anas strepera Mallard Anas platyrchynchos Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina Common Pochard Aythya ferina Ferrugineous Duck Aythya nyroca Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis Great Crested Grebe Podiceps cristatus Black-necked Grebe Podiceps nigricollis Red-necked Grebe Podiceps grisegena Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan* Pygmy Cormorant Phalacrocorax pygmeus White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus Great Bittern Botaurus stellaris* Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus Night Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides Little Egret Egretta garzetta Great White Egret Egretta alba Grey Heron Ardea cinerea Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus Eurasian Spoonbill Platalea leucorodia Eurasian Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla Short-toed Eagle Circaetus gallicus Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus Pallid Harrier Circus macrourus* Montagu`s Herrier Circus pygargus Levant Sparrohawk Accipiter -

2019 Trip Report Available Here

Ronda and the Straits – the unknown Vulture spectacle! Friday 18th October – Thursday 24th October Report by Beth Aucott www.ingloriousbustards.com Friday 18th October After an early start we arrived at Malaga airport about midday where we met Niki and the first member of our group Margaret. After introductions, the four of us set off in one of the vehicles whilst Simon met the rest of the group and it wasn’t long before we were travelling in convoy on our way to our first base, Huerta Grande - a beautiful eco-lodge snuggled into cork-oak woodland. Over a light lunch, and a glass of wine, we met the rest of the group, Alexia, Glenn, Carla, Chris and Colin as we watched Crested Tits come into the feeders. It felt bizarre to be watching these funky little birds in shorts and t-shirt when then the only time I’d seen them before had been in the snow in Scotland! We had time to settle in and have a quick wander around the grounds. Our list started to grow with sightings of Nuthatch, Short-toed Treecreeper, Long-legged Buzzard, Booted Eagle, Sand Martin, House Martin, Barn and Red-rumped Swallow. Fleeting views of Two-tailed Pasha and Geranium Bronze also went down well as welcome additions to the butterfly list. We then headed out to Punta Carnero and spent some time at a little viewpoint on the coast. From here we watched a couple of Ospreys fishing as we looked across the straits to Africa. Red-rumped Swallows and Crag Martins whizzed overhead, sharing the sky with Hobby, Sparrowhawk and Peregrine. -

Western Birds

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 41, Number 2, 2010 NOTEWORTHY BIRD OBSERVATIONS FROM THE CAROLINE AND MARSHALL ISLANDS 1988–2009, INCLUDING FIVE NEW RECORDS FOR MICRONESIA H. DOUGLAS PRATT, North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences, 11 W. Jones St., Raleigh, North Carolina 27601; [email protected] MARJORIE FALANRUW, Yap Institute of Natural Science, P. O. Box 215, Yap, Federated States of Micronesia 96943 MANDY T. ETPISON, Etpison Museum, P. O. Box 7049, Koror, Palau 96940 ALAN OLSEN, Natural History Section, Belau National Museum, P. O. Box 666, Koror, Palau 96940 DONALD W. BUDEN, Division of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, College of Micronesia-FSM, P. O. Box 159, Kolonia, Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia 96941 PETER CLEMENT, 69 Harecroft Road, Wisbech, Cambridgeshire PE13 1RL, England ANURADHA GUPTA, HEATHER KETEBENGANG, and YALAP P. YALAP, Palau Conservation Society, P. O. Box 1811, Koror, Palau 96940 DALE R. HERTER, Raedeke Associates, Inc., 5711 NE 63rd Street, Seattle, Wash- ington 98115 DAVID KLAUBER, 7 Julian Street, Hicksville, New York 11801 PAUL PISANO, 628 18th Street S, Arlington, Virginia 22202 DANIEL S. VICE, U. S. Department of Agriculture, APHIS, Wildlife Services, Hawaii, Guam, and Pacific Islands, 233 Pangelinan Way, Barrigada, Guam 96913 GARY J. WILES, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 600 Capitol Way North, Olympia, Washington 98501-1091 ABSTRACT: We evaluate previously unpublished or semi-published reports of 61 migratory, 3 resident, and 1 failed introduced species or subspecies of birds in Micronesia