Arxiv:0902.1137V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 6 Feb 2009 02Frareview)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Nebulae

Planetary Nebulae A planetary nebula is a kind of emission nebula consisting of an expanding, glowing shell of ionized gas ejected from old red giant stars late in their lives. The term "planetary nebula" is a misnomer that originated in the 1780s with astronomer William Herschel because when viewed through his telescope, these objects appeared to him to resemble the rounded shapes of planets. Herschel's name for these objects was popularly adopted and has not been changed. They are a relatively short-lived phenomenon, lasting a few tens of thousands of years, compared to a typical stellar lifetime of several billion years. The mechanism for formation of most planetary nebulae is thought to be the following: at the end of the star's life, during the red giant phase, the outer layers of the star are expelled by strong stellar winds. Eventually, after most of the red giant's atmosphere is dissipated, the exposed hot, luminous core emits ultraviolet radiation to ionize the ejected outer layers of the star. Absorbed ultraviolet light energizes the shell of nebulous gas around the central star, appearing as a bright colored planetary nebula at several discrete visible wavelengths. Planetary nebulae may play a crucial role in the chemical evolution of the Milky Way, returning material to the interstellar medium from stars where elements, the products of nucleosynthesis (such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and neon), have been created. Planetary nebulae are also observed in more distant galaxies, yielding useful information about their chemical abundances. In recent years, Hubble Space Telescope images have revealed many planetary nebulae to have extremely complex and varied morphologies. -

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Für Astronomie Nr

für Astronomie Nr. 28 Zeitschrift der Vereinigung der Sternfreunde e.V. / VdS DAS WELTALL Orionnebel DU LEBST DARIN – ENTDECKE ES! Computerastronomie Internationales Jahr der Astronomie INTERNATIONALES ISSN 1615 - 0880 www.vds-astro.de I/ 2009 ASTRONOMIEJAHR [email protected] • www.astro-shop.com Tel.: 040/5114348 • Fax: 040/5114594 Eiffestr. 426 • 20537 Hamburg Astroart 4.0 The Night Sky Observer´s Guide Photoshop Astronomy Die aktuellste Version Dieses hilfreiche Werk Der Autor arbeitet seit fast 10 Jahren mit Photo- des bekannten Bildbe- dient der erfolg- shop, um seine Astrofotos zu bearbeiten. Die arbeitungspro- reichen Vorbereitung dabei gemachten Erfahrungen hat er in diesem grammes gibt es jetzt einer abwechslungs- speziell auf die Bedürfnisse des Amateurastro- mit interessanten reichen Deep-Sky- nomen zugeschnitte- neuen Funktionen. Nacht. Sortiert nach nen Buch gesammelt. Moderne Dateifor- Sternbildern des Die behandelten The- men sind unter ande- mate wie DSLR-RAW Sommer- und Win- rem: die technische werden unterstützt, terhimmels nden Ausstattung, Farbma- Bilder können sich detaillierte NEU nagement, Histo- durch automa- Beschreibungen Südhimmel gramme, Maskie- 3. Band tische Sternfelderken- zu hunderten rungstechniken, nung direkt überlagert werden, was die Bild- Galaxien, Nebeln, Oenen Stern- und Addition mehrerer feldrotation vernachlässigbar macht. Auch die Kugelhaufen. Der Teleskopanblick jedes Bilder, Korrektur von Bearbeitung von Farbbildern wurde erweitert. Objekts ist beschrieben und mit einem Hin- Vignettierungen, Besonderes Augenmerk liegt auf der Erken- weis bezüglich der verwendeten Optik verse- Farbhalos, Deformationen oder nung und Behandlung von Pixelfehlern der hen. 2 Bände mit insgesamt 446 Fotos, 827 überbelichteten Sternen, LRGB und vieles Aufnahme-Chips. Zeichnungen, 143 Tabellen und 431 Sternkar- mehr. Auf der beigefügten DVD benden sich 90 alle im Buch besprochenen und verwendeten Update ten. -

A New Radio Spectral Line Survey of Planetary Nebulae: Exploring Radiatively Driven Heating and Chemistry of Molecular Gas

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 12-18-2017 A New Radio Spectral Line Survey of Planetary Nebulae: Exploring Radiatively Driven Heating and Chemistry of Molecular Gas Jesse Bublitz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Bublitz, Jesse, "A New Radio Spectral Line Survey of Planetary Nebulae: Exploring Radiatively Driven Heating and Chemistry of Molecular Gas" (2017). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A New Radio Spectral Line Survey of Planetary Nebulae: Exploring Radiatively Driven Heating and Chemistry of Molecular Gas Jesse Bublitz AThesisSubmittedinPartialFulfillmentofthe Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in in Astrophysical Sciences & Technology School of Physics and Astronomy College of Science Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, NY December 18, 2017 Abstract Planetary nebulae contain shells of cold gas and dust whose heating and chemistry is likely driven by UV and X-ray emission from their central stars and from wind-collision-generated shocks. We present the results of a survey of molecular line emissions in the 88 - 235 GHz range from nine nearby (<1.5 kpc) planetary nebulae using the 30 m telescope at the Insti- tut de Radioastronomie Millim´etrique. Rotational transitions of nine molecules, including the well-studied CO isotopologues and chemically important trace species, were observed and the results compared with and augmented by previous studies of molecular gas in PNe. -

OCTOBER 2013 OT H E D Ebn V E R S E R V EOCTOBERR 2013

THE DENVER OBSERVER OCTOBER 2013 OT h e D eBn v e r S E R V EOCTOBERR 2013 P H O T O O P P S G A L O R E — G E A R U P ! ! SISTER GALAXY—THE ANDROMEDA GALAXY (M31 OR NGC 224) The Andromeda galaxy is one of the closest galaxies to our own. At only 2.5 million light-years away, it Calendar spans about 170 arc-minutes of sky which is over three times the diameter of the moon! Although that distance in light years equates to 393,121,310,400,000,000 km, it is still close enough to see in incredi- 4.......................................... New moon ble detail. Because of its close proximity, Andromeda is fairly easy to image because it is bright enough to capture in short exposures. The images that comprise this image were taken on November 1, 2008 at 11............................ First quarter moon the CSAS site near Gardner, CO. with a Canon EOS Digital Rebel XTi using a Canon 200 mm f/4L lens 18......................................... Full moon riding atop a Meade 10-inch LX200GPS on an equatorial wedge. There are a total of 13 60-second im- ages stacked together to render this image. Stacking and editing was accomplished using Images Plus. 26........................... Last quarter moon Image © Scott Leach Inside the Observer OCTOBER SKIES by Dennis Cochran he Canadian astronomy magazine Sky News (from comet Giacobini-Zinner) on the 8th, then on President’s Message......................... 2 T informs us that on October 11, there will be the 10th we’ll see the Southern Taurids (from comet three—count ’em—three moon shadows on Enke). -

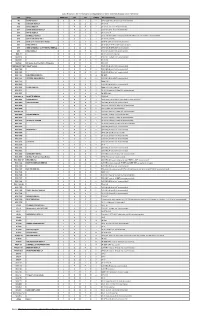

Catalogue of Excitation Classes P for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae

Catalogue of Excitation Classes p for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae Name p Name p Name p Name p NeC 40 1 Nee 6072 9 NeC 6881 10 IC 4663 11 NeC 246 12+ Nee 6153 3 NeC 6884 7 IC 4673 10 NeC 650-1 10 Nee 6210 4 NeC 6886 9 IC 4699 9 NeC 1360 12 Nee 6302 10 Nee 6891 4 IC 4732 5 NeC 1501 10 Nee 6309 10 NeC 6894 10 IC 4776 2 NeC 1514 8 NeC 6326 9 Nee 6905 11 IC 4846 3 NeC 1535 8 Nee 6337 11 Nee 7008 11 IC 4997 8 NeC 2022 12 Nee 6369 4 NeC 7009 7 IC 5117 6 NeC 2242 12+ NeC 6439 8 NeC 7026 9 IC 5148-50 6 NeC 2346 9 NeC 6445 10 Nee 7027 11 IC 5217 6 NeC 2371-2 12 Nee 6537 11 Nee 7048 11 Al 1 NeC 2392 10 NeC 6543 5 Nee 7094 12 A2 10 NeC 2438 10 NeC 6563 8 NeC 7139 9 A4 10 NeC 2440 10 NeC 6565 7 NeC 7293 7 A 12 4 NeC 2452 10 NeC 6567 4 Nee 7354 10 A 15 12+ NeC 2610 12 NeC 6572 7 NeC 7662 10 A 20 12+ NeC 2792 11 NeC 6578 2 Ie 289 12 A 21 1 NeC 2818 11 NeC 6620 8 IC 351 10 A 23 4 NeC 2867 9 NeC 6629 5 Ie 418 1 A 24 1 NeC 2899 10 Nee 6644 7 IC 972 10 A 30 12+ NeC 3132 9 NeC 6720 10 IC 1295 10 A 33 11 NeC 3195 9 NeC 6741 9 IC 1297 9 A 35 1 NeC 3211 10 NeC 6751 9 Ie 1454 10 A 36 12+ NeC 3242 9 Nee 6765 10 IC1747 9 A 40 2 NeC 3587 8 NeC 6772 9 IC 2003 10 A 41 1 NeC 3699 9 NeC 6778 9 IC 2149 2 A 43 2 NeC 3918 9 NeC 6781 8 IC 2165 10 A 46 2 NeC 4071 11 NeC 6790 4 IC 2448 9 A 49 4 NeC 4361 12+ NeC 6803 5 IC 2501 3 A 50 10 NeC 5189 10 NeC 6804 12 IC 2553 8 A 51 12 NeC 5307 9 NeC 6807 4 IC 2621 9 A 54 12 NeC 5315 2 NeC 6818 10 Ie 3568 3 A 55 4 NeC 5873 10 NeC 6826 11 Ie 4191 6 A 57 3 NeC 5882 6 NeC 6833 2 Ie 4406 4 A 60 2 NeC 5879 12 NeC 6842 2 IC 4593 6 A -

A Dynamo Mechanism As the Potential Origin of the Long Cycle in Double Periodic Variables Dominik R

A&A 602, A109 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201628900 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics A dynamo mechanism as the potential origin of the long cycle in double periodic variables Dominik R. G. Schleicher and Ronald E. Mennickent Departamento de Astronomía, Facultad Ciencias Físicas y Matemáticas, Universidad de Concepción, Av. Esteban Iturra s/n Barrio Universitario, Casilla 160-C, Concepción, Chile e-mail: [email protected] Received 11 May 2016 / Accepted 9 March 2017 ABSTRACT The class of double period variables (DPVs) consists of close interacting binaries, with a characteristic long period that is an order of magnitude longer than the corresponding orbital period, many of them with a characteristic ratio of approximately 35. We consider here the possibility that the accretion flow is modulated as a result of a magnetic dynamo cycle. Due to the short binary separations, we expect the rotation of the donor star to be synchronized with the rotation of the binary due to tidal locking. We here present a model to estimate the dynamo number and the resulting relation between the activity cycle length and the orbital period, as well as an estimate for the modulation of the mass transfer rate. The latter is based on Applegate’s scenario, implying cyclic changes in the radius of the donor star and thus in the mass transfer rate as a result of magnetic activity. Our model is applied to a sample of 17 systems with known physical parameters, 11 of which also have known modulation periods. In spite of the uncertainties of our simplified framework, the results show a reasonable agreement, indicating that a dynamo interpretation is potentially feasible. -

Annual Report 2010

Research Institute Leiden Observatory (Onderzoekinstituut Sterrewacht Leiden) Annual Report 2010 Sterrewacht Leiden Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences Leiden University Niels Bohrweg 2 Postbus 9513 2333 CA Leiden 2330 RA Leiden The Netherlands http://www.strw.leidenuniv.nl Cover: In the Sackler Laboratory for Astrophysics, the circumstances in the inter- and circumstellar medium are simulated. In 2010, water was successfully made on icy dust grains by H-atom bombardment, understanding was gained how complex molecules form under the extreme conditions that are typical for space, and experiments are now ongoing that investigate under which conditions the building blocks of life form. The picture shows the lab’s newest setup - MATRI2CES - that has been constructed with the aim to 'unlock the chemistry of the heavens'. An electronic version of this annual report is available on the web at http://www.strw.leidenuniv.nl/research/annualreport.php?node=23 Production Annual Report 2010: A. van der Tang, E. Gerstel, F.P. Israel, J. Lub, M. Israel, E. Deul Sterrewacht Leiden Executive (Directie Onderzoeksinstituut) Director K. Kuijken Wetenschappelijk Directeur Director of Education F.P. Israel Onderwijs Directeur Institute Manager E. Gerstel Instituutsmanager Supervisory Council (Raad van advies) Prof. Dr. Ir. J.A.M. Bleeker (Chair) Dr. B. Baud Drs. J.F. van Duyne Prof. Dr. K. Gaemers Prof. Dr. C. Waelkens CONTENTS Contents: Part I Chapter 1 1.1 Foreword 1 1.2 Obituary Adriaan Blaauw 5 1.3 Obituary Jaap Tinbergen 7 Chapter 2 2.1 Heritage 11 2.2 Extrasolar planets 13 2.3 Circumstellar gas and dust 15 2.4 Chemistry and physics of the interstellar medium 20 2.5 Stars 25 2.6 Galaxies of the Local Group 30 2.7 Nearby galaxies: observations and theory 37 2.8. -

Abstracts of Talks 1

Abstracts of Talks 1 INVITED AND CONTRIBUTED TALKS (in order of presentation) Milky Way and Magellanic Cloud Surveys for Planetary Nebulae Quentin A. Parker, Macquarie University I will review current major progress in PN surveys in our own Galaxy and the Magellanic clouds whilst giving relevant historical context and background. The recent on-line availability of large-scale wide-field surveys of the Galaxy in several optical and near/mid-infrared passbands has provided unprecedented opportunities to refine selection techniques and eliminate contaminants. This has been coupled with surveys offering improved sensitivity and resolution, permitting more extreme ends of the PN luminosity function to be explored while probing hitherto underrepresented evolutionary states. Known PN in our Galaxy and LMC have been significantly increased over the last few years due primarily to the advent of narrow-band imaging in important nebula lines such as H-alpha, [OIII] and [SIII]. These PNe are generally of lower surface brightness, larger angular extent, in more obscured regions and in later stages of evolution than those in most previous surveys. A more representative PN population for in-depth study is now available, particularly in the LMC where the known distance adds considerable utility for derived PN parameters. Future prospects for Galactic and LMC PN research are briefly highlighted. Local Group Surveys for Planetary Nebulae Laura Magrini, INAF, Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri The Local Group (LG) represents the best environment to study in detail the PN population in a large number of morphological types of galaxies. The closeness of the LG galaxies allows us to investigate the faintest side of the PN luminosity function and to detect PNe also in the less luminous galaxies, the dwarf galaxies, where a small number of them is expected. -

Free Astronomy Magazine May-June 2020

cover EN.qxp_l'astrofilo 27/04/2020 16:36 Page 1 THE FREE MULTIMEDIA MAGAZINE THAT KEEPS YOU UPDATED ON WHAT IS HAPPENING IN SPACE Bi-monthly magazine of scientific and technical information ✶ May-June 2020 BBiioofflluuoorreesscceenntt ppllaanneetsts The star S2 moves according to Einstein’s Relativity Do sub-relativistic meteors exist? www.astropublishing.com ✶✶www.facebook.com/astropublishing [email protected] colophon EN_l'astrofilo 27/04/2020 16:36 Page 2 colophon EN_l'astrofilo 27/04/2020 16:36 Page 3 S U M M A R Y BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION The star S2 moves according to Einstein’s Relativity FREELY AVAILABLE THROUGH Observations made with ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) have revealed for the first time that a star or- THE INTERNET biting the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way moves just as predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Its orbit is shaped like a rosette and not like an ellipse as predicted by... May-June 2020 4 Biofluorescent planets The closest potentially habitable rocky exoplanets all orbit around red dwarfs. These types of stars are particularly suitable for hosting Earth-sized planets, but they are also characterized by surface phenom- 10 ena very harmful to life as we know it. Some organisms, however, may be able to adapt to intense... ESO telescope observes exoplanet where it rains iron Researchers using ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) have observed an extreme planet where they suspect it rains iron. The ultra-hot giant exoplanet has a day side where temperatures climb above 2400 degrees 22 Celsius, high enough to vaporise metals. -

Zur Objektauswahl: Nummer Anklicken Sternbild- Übersicht NGC

NGC-Objektauswahl Cygnus NGC 6764 NGC 6856 NGC 6910 NGC 6995 NGC 7031 NGC 7082 NGC 6798 NGC 6857 NGC 6913 NGC 7037 NGC 7086 NGC 6801 NGC 6866 NGC 6914 NGC 6996 NGC 7039 NGC 7092 NGC 6811 NGC 6871 NGC 6916 NGC 6997 NGC 7044 NGC 7093 NGC 6819 NGC 6874 NGC 6946 NGC 7000 NGC 7048 NGC 7116 NGC 6824 NGC 6881 NGC 6960 NGC 7008 NGC 7050 NGC 7127 NGC 6826 NGC 6883 NGC 6974 NGC 7013 NGC 7058 NGC 7128 NGC 6833 NGC 6884 NGC 6979 NGC 7024 NGC 7062 NGC 6834 NGC 6888 NGC 6991 NGC 7026 NGC 7063 NGC 6846 NGC 6894 NGC 6992 NGC 7027 NGC 7067 Sternbild- Übersicht Zur Objektauswahl: Nummer anklicken Sternbildübersicht Auswahl NGC 6764 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6798 _6801_6824_Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6811 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6819 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6826 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6833 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6834 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6846_6857 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6856 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6866_6884 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6871_6883 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6874_6881_6888_6913 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6894 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6910_6914 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6916_6946 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6960_6974_6979_6992_6995_7013 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC6991_96_97_7000_26_39_48 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 7008_7031_7058_7086_7127_7128 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 7024_7027_7044 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl N 7037_7050_7063 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 7062_7067_7082_7092_7093 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 7116 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 6764_Übersichtskarte Aufsuch- Auswahl karte NGC 6798 Übersichtskarte Aufsuch- Auswahl karte NGC 6801 Übersichtskarte Aufsuch- -

Dave Knisely's Filter Performance Comparisons for Some Common Nebulae Quick Reference

Dave Knisely's Filter Performance Comparisons For Some Common Nebulae Quick Reference Ref Name DEEP-SKY UHC OIII H-BETA Recommendation M1 CRAB NEBULA 3 4 3 0 UHC/DEEP-SKY (H-beta *not* recommended) M8 LAGOON NEBULA 3 5 5 2 UHC/OIII M16 EAGLE NEBULA 2 4 4 2 UHC/OIII, but H-BETA hurts the view M17 SWAN (OMEGA) NEBULA 3 4 5 1 OIII/UHC (H-BETA not recommended) M20 TRIFID NEBULA 2 4 3 4 UHC/H-BETA M27 DUMBELL NEBULA 3 5 4 1 UHC (OIII also useful in showing some inner detail, but H-BETA is NOT recommended) M42 GREAT ORION NEBULA 3 5 4 3 UHC/OIII (near-tie) M43 North part of Great Orion Nebula 3 3 2 4 H-BETA (UHC and Deep-Sky also help) M57 RING NEBULA 2 4 4 0 UHC/OIII (H-BETA is NOT recommended!) M76 “MINI-DUMBELL” or BUTTERFLY NEBULA 2 4 3 0 UHC/OIII (H-BETA NOT recommended!) M97 OWL NEBULA 2 4 5 0 OIII/UHC (H-beta *not* recommended) NGC 40 3 3 2 2 DEEP-SKY/UHC (near tie) NGC 246 2 3 4 0 OIII/UHC. (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 281 3 4 4 2 UHC/OIII. NGC 604 HII region in galaxy M33 in Triangulum 2 3 4 2 OIII/UHC NGC 896/IC 1795 “Heart” nebula 3 4 4 1 UHC/OIII (H-beta *not* recommended) NGC 1360 2 4 4 0 OIII/UHC (H-beta *not* recommended) NGC 1491 3 5 4 0 UHC/OIII (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 1499 CALIFORNIA NEBULA 2 2 1 4 H-BETA NGC 1514 CRYSTAL-BALL NEBULA 2 4 4 0 OIII/UHC (H-Beta NOT recommended) NGC 1999 2 1 1 1 DEEP-SKY NGC 2022 3 4 5 0 OIII/UHC (H-Beta NOT recommended) NGC 2024 FLAME NEBULA 3 3 2 1 DEEP-SKY/UHC (near tie) NGC 2174 2 4 4 0 UHC/OIII (near tie) (H-Beta NOT recommended) NGC 2327 2 3 2 4 H-BETA/UHC NGC 2237-9 ROSETTE NEBULA 2 5 5 1 UHC/OIII NGC 2264 CONE NEBULA 2 3 2 1 UHC (other filters may be more useful in larger apertures) NGC 2359 THOR’S HELMET 2 4 5 0 OIII/UHC (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 2346 2 3 3 0 UHC/OIII (near tie) (H-beta *not* recommended) NGC 2438 2 3 4 0 OIII (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 2371-2 2 4 4 0 OIII/UHC (near tie) (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 2392 ESKIMO NEBULA 2 4 4 0 OIII/UHC.