Regional Development in Ukraine: Priority Actions in Terms of Decentralization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Book Progeo 2Ed 20

Abstract Book BUILDING CONNECTIONS FOR GLOBAL GEOCONSERVATION Editors: G. Lozano, J. Luengo, A. Cabrera Internationaland J. Vegas 10th International ProGEO online Symposium ABSTRACT BOOK BUILDING CONNECTIONS FOR GLOBAL GEOCONSERVATION Editors Gonzalo Lozano, Javier Luengo, Ana Cabrera and Juana Vegas Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 2021 Building connections for global geoconservation. X International ProGEO Symposium Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 2021 Lengua/s: Inglés NIPO: 836-21-003-8 ISBN: 978-84-9138-112-9 Gratuita / Unitaria / En línea / pdf © INSTITUTO GEOLÓGICO Y MINERO DE ESPAÑA Ríos Rosas, 23. 28003 MADRID (SPAIN) ISBN: 978-84-9138-112-9 10th International ProGEO Online Symposium. June, 2021. Abstracts Book. Editors: Gonzalo Lozano, Javier Luengo, Ana Cabrera and Juana Vegas Symposium Logo design: María José Torres Cover Photo: Granitic Tor. Geosite: Ortigosa del Monte’s nubbin (Segovia, Spain). Author: Gonzalo Lozano. Cover Design: Javier Luengo and Gonzalo Lozano Layout and typesetting: Ana Cabrera 10th International ProGEO Online Symposium 2021 Organizing Committee, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Juana Vegas Andrés Díez-Herrero Enrique Díaz-Martínez Gonzalo Lozano Ana Cabrera Javier Luengo Luis Carcavilla Ángel Salazar Rincón Scientific Committee: Daniel Ballesteros Inés Galindo Silvia Menéndez Eduardo Barrón Ewa Glowniak Fernando Miranda José Brilha Marcela Gómez Manu Monge Ganuzas Margaret Brocx Maria Helena Henriques Kevin Page Viola Bruschi Asier Hilario Paulo Pereira Carles Canet Gergely Horváth Isabel Rábano Thais Canesin Tapio Kananoja Joao Rocha Tom Casadevall Jerónimo López-Martínez Ana Rodrigo Graciela Delvene Ljerka Marjanac Jonas Satkünas Lars Erikstad Álvaro Márquez Martina Stupar Esperanza Fernández Esther Martín-González Marina Vdovets PRESENTATION The first international meeting on geoconservation was held in The Netherlands in 1988, with the presence of seven European countries. -

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

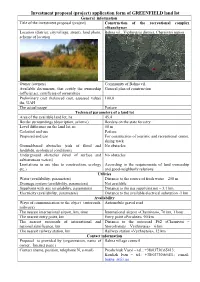

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

Ukraine Grain Ports Outlook - 2018 the History of Grain Is the History of Odessa 2018- Population Sensus 1892

Ukraine grain ports outlook - 2018 The history of grain is the history of Odessa 2018- Population sensus 1892 1794-1917 1991- 1917 1917 1918-1920 1941-1944 1918 1918-1920 1920-1991 1794-2018 Humble beginnings – but not much change Comparison of cost – America vs Ukraine 1880 America - Ukraine River transport 7 22 Railroad 5 31 Transshipment 3 40 ‘’Kopek’’ per 360 pounds The port of Odessa is of particular disadvantage since only one railway line ties to the interior 1871 – 71% of grain reach Odessa by rail ‘’French Consul Odessa 1907’’ Grain export 1911 Odessa second rail line opens 1913 Odessa-Bakhmach Odessa – 1.6 mill tons Nikolaev – 1.5 mill tons Odessa is the only deep sea port and the other ports Nikolaev and Kherson have Kherson – 1 mill tons To send their grain in barges to Ochakov and Odessa to be loaded onto vessel ‘’United States Consul Odessa 1913’’ 1890 – First Grain Elevator is built 1860 Dreyfuss establish branch in Odessa Inland transport was (still is) a major problem – the cost of There is no roads outside Odessa transporting grain from suburbs of Odessa to port ‘’Italian 1905’’ was same as from Chicago to New York 1 silver penny sterling = 32 wheat grains ‘’French Consul Odessa 1879’’ 1 Sumerian shekel = weight of 180 wheat grains 1 Inch = 3 medium sized barley corns places end to end (2.54 cm) Challenges in 19th Century and today • Lack of Grain Quality control and standards • Poor infrastructure – roads and rail • High inland cost on railroad and lack of capacity • Transshipment rates high versus elsewhere • Buying -

Local and Regional Government in Ukraine and the Development of Cooperation Between Ukraine and the EU

Local and regional government in Ukraine and the development of cooperation between Ukraine and the EU The report was written by the Aston Centre for Europe - Aston University. It does not represent the official views of the Committee of the Regions. More information on the European Union and the Committee of the Regions is available on the internet at http://www.europa.eu and http://www.cor.europa.eu respectively. Catalogue number: QG-31-12-226-EN-N ISBN: 978-92-895-0627-4 DOI: 10.2863/59575 © European Union, 2011 Partial reproduction is allowed, provided that the source is explicitly mentioned Table of Contents 1 PART ONE .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction..................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Overview of local and regional government in Ukraine ................................ 3 1.3 Ukraine’s constitutional/legal frameworks for local and regional government 7 1.4 Competences of local and regional authorities............................................... 9 1.5 Electoral democracy at the local and regional level .....................................11 1.6 The extent and nature of fiscal decentralisation in Ukraine .........................15 1.7 The extent and nature of territorial reform ...................................................19 1.8 The politics of Ukrainian administrative reform plans.................................21 1.8.1 Position of ruling government ..................................................................22 -

Epidemiology of Parkinson's Disease in the Southern Ukraine

— !!!cifra_MNJ_№5_(tom16)_2020 01.07. Белоусова 07.07.Евдокимова ОРИГІНАЛЬНІ ДОСЛІДЖЕННЯ /ORIGINAL RESEARCHES/ UDC 616.858-036.22 DOI: 10.22141/2224-0713.16.5.2020.209248 I.V. Hubetova Odessa Regional Clinical Hospital, Odesa, Ukraine Odessa National Medical University, Odesa, Ukraine Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease in the Southern Ukraine Abstract. Background. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a slowly progressing neurodegenerative disease with accumulation of alpha-synuclein and the formation of Lewy bodies inside nerve cells. The prevalence of PD ranges from 100 to 200 cases per 100,000 population. However, in the Ukrainian reality, many cases of the disease remain undiagnosed, which affects the statistical indicators of incidence and prevalence. The purpose of the study is to compare PD epidemiological indices in the Southern Ukraine with all-Ukrainian rates. Material and methods. Statistical data of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, public health departments of Odesa, Mykolaiv and Kherson regions for 2015–2017 were analyzed. There were used the methods of descriptive statistics and analysis of variance. Results. Average prevalence of PD in Ukraine is 67.5 per 100,000 population — it is close to the Eastern European rate. The highest prevalence was registered in Lviv (142.5 per 100,000), Vinnytsia (135.9 per 100,000), Cherkasy (108.6 per 100,000) and Kyiv (107.1 per 100,000) regions. The lowest rates were in Luhansk (37.9 per 100,000), Kyrovohrad (42.5 per 100,000), Chernivtsi (49.0 per 100,000) and Ternopil (49.6 per 100,000) regions. In the Southern Ukraine, the highest prevalence of PD was found in Mykolaiv region. -

Perception of Local Geographical Specificity by the Population of Podolia

88 ЕКОНОМІЧНА ТА СОЦІАЛЬНА ГЕОГРАФІЯ PERCEPTION OF LOCAL GEOGRAPHICAL SPECIFICITY BY THE POPULATION OF PODOLIA Oleksiy GNATIUK Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine [email protected] Abstract: The article reveals the perception of local geographical specificity by the population of Podolia. Attention is focused on five elements of the local geographical specificity: natural, historical and cultural monuments; prominent personalities; trademarks and producers of goods and services; the origin settlement names; figurative poetic names of settlements. The tasks were the following: to determine basic qualitative and quantitative parameters of regional image-geographical systems, to find the main regularities of their spatial organization, and, finally, to classify administrative-territorial units of the region according to the basic properties of image-geographic systems using specially worked out method. Analysis made it clear that the population of Podolia is characterized by a high level of reflection of the local geographic specificity. Local image-geographical systems from different parts of the region have different structure and level of development. In particular, image-geographical systems in Vinnytsia and Ternopil oblasts are well developed, stable and hierarchized, in Khmelnitskyi oblast it is just developing, dynamic and so quite unstable. To further disclosure the regularities and patterns of local geographical specificity perception, it is advisable to carry out case studies of image-geographic systems at the level of individual settlements. Key words: territorial identity, local geographical specificity, geographic image UDC: 911.3 СПРИЙНЯТТЯ МІСЦЕВОЇ ГЕОГРАФІЧНОЇ СПЕЦИФІКИ НАСЕЛЕННЯМ ПОДІЛЛЯ Олексій ГНАТЮК Київський національний університет імені Тараса Шевченка, Україна [email protected] Анотація: У статті розглянуто сприйняття місцевої географічної специфіки населенням Подільського регіону. -

Geographic Information System Development (Data Collection And

Geographic Information System Development (Data collection and processing) Deliverable No.: D.02.01 GA 2. Geographic Information System Development, activities 2.1 – 2.2 RESPONSIBLE: TEI Kentrikis Makedonias (ENPI Beneficiary) INVOLVED PARTNERS: ALL Black Sea JOP, “SCInet NatHaz” Data collection and processing Project Details Programme Black Sea JOP Priority and Measure Priority 2 (Sharing resources and competencies for environmental protection and conservation), Measure 2.1. (Strengthening the joint knowledge and information base needed to address common challenges in the environmental protection of river and maritime systems) Objective Development of a Scientific Network A Scientific Network for Earthquake, Landslide and Flood Hazard Prevention Project Title Project Acronym SCInet NatHaz Contract No MIS-ETC 2614 Deliverable-No. D.02.01 Final Version Issue: I.07 Date: 31st January 2014 Page: 2of 28 Black Sea JOP, “SCInet NatHaz” Data collection and processing Lead Partner TEI OF KENTRIKI MAKEDONIA, GREECE Total Budget 700.000,00 Euro (€) Time Frame Start Date – End Date 01/05/2013 – 30/04/2015 Book Captain: K. PAPATHEODOROU (TEI KENTRIKIS MAKEDONIAS) Contributing K. Papatheodorou, K. Ntouros, A. Tzanou, N. Klimis, S. Authors: Skias, H. Aksoy, O. Kirca, G. Celik, B. Margaris, N. Theodoulidis, A. Sidorenko, O. Bogdevich, K. Stepanova, O. Rubel, N. Fedoronchuk, L. Tofan, M.J. Adler, Z. Prefac, V. Nenov, H. Yermendjiev, A. Ansal, G. Tonuk, M. Demorcioglou Deliverable-No. D.02.01 Final Version Issue: I.07 Date: 31st January 2014 Page: 3of 28 Black Sea JOP, “SCInet NatHaz” Data collection and processing Document Release Sheet Book captain: K. PAPATHEODOROU (TEI Sign Date KENTRIKIS MAKEDONIAS) 31.01.2014 Approval K. -

Odessa Intercultural Profile

City of Odessa Intercultural Profile This report is based upon the visit of the CoE expert team on 30 June & 1 July 2017, comprising Irena Guidikova, Kseniya Khovanova-Rubicondo and Phil Wood. It should ideally be read in parallel with the Council of Europe’s response to Odessa’s ICC Index Questionnaire but, at the time of writing, the completion of the Index by the City Council is still a work in progress. 1. Introduction Odessa (or Odesa in Ukrainian) is the third most populous city of Ukraine and a major tourism centre, seaport and transportation hub located on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. Odessa is also an administrative centre of the Odessa Oblast and has been a multiethnic city since its formation. The predecessor of Odessa, a small Tatar settlement, was founded in 1440 and originally named Hacıbey. After a period of Lithuanian control, it passed into the domain of the Ottoman Sultan in 1529 and remained in Ottoman hands until the Empire's defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1792. In 1794, the city of Odessa was founded by decree of the Empress Catherine the Great. From 1819 to 1858, Odessa was a free port, and then during the twentieth century it was the most important port of trade in the Soviet Union and a Soviet naval base and now holds the same prominence within Ukraine. During the 19th century, it was the fourth largest city of Imperial Russia, and its historical architecture has a style more Mediterranean than Russian, having been heavily influenced by French and Italian styles. -

QUARTERLY REPORT for the Implementation of the PULSE Project

QUARTERLY REPORT for the implementation of the PULSE Project APRIL – JUNE, 2020 (²I² QUARTER OF US FISCAL YEAR 2020) EIGHTEENTH QUARTER OF THE PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION QUARTERLY REPORT for the implementation of the PULSE Project TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations 4 Resume 5 Chapter 1. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN THE REPORTING QUARTER 5 Chapter 2. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 7 Expected Result 1: Decentralisation enabling legislation reflects local government input 7 1.1. Local government officials participate in sectoral legislation drafting 8 grounded on the European sectoral legislative principles 1.1.1. Preparation and approval of strategies for sectoral reforms 8 1.1.2. Preparation of sectoral legislation 24 1.1.3. Legislation monitoring 33 1.1.4. Resolving local government problem issues and promotion of sectoral reforms 34 1.2. Local governments and all interested parties are actively engaged and use 40 participatory tool to work on legislation and advocating for its approval 1.2.1 Support for approval of drafted legislation in the parliament: 40 tools for interaction with the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 1.2.2 Support to approval of resolutions and directives of the Cabinet of Ministers: 43 tools for interaction with the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine 1.3. Local governments improved their practice and quality of services 57 because of the sound decentralised legislative basis for local governments 1.3.1. Legal and technical assistance 57 1.3.2. Web-tools to increase the efficiency of local government activities 57 1.3.3. Feedback: receiving and disseminating 61 Expected Result 2: Resources under local self-governance authority increased 62 2.1. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Wildcat (Felis Silvestris Schreber, 1777) in Ukraine: Modern State of the Populations and Eastwards

WILDCAT (FELIS SILVESTRIS SCHREBER, 1777) IN UKRAINE: MODERN STATE OF THE POPULATIONS AND EASTWARDS... 233 UDC 599.742.73(477) WILDCAT (FELIS SILVESTRIS SCHREBER, 1777) IN UKRAINE: MODERN STATE OF THE POPULATIONS AND EASTWARDS EXPANSION OF THE SPECIES I. Zagorodniuk1, M. Gavrilyuk2, M. Drebet3, I. Skilsky4, A. Andrusenko5, A. Pirkhal6 1 National Museum of Natural History, NAS of Ukraine 15, Bohdan Khmelnytskyi St., Kyiv, 01601, Ukraine e-mail: [email protected] 2 Bohdan Khmelnitsky National University of Cherkasy 81, Shevchenko Blvd., Cherkasy 18031, Ukraine 3 National Nature Park “Podilski Tovtry” 6, Polskyi Rynok Sq., Kamianets-Podilskyi 32301, Khmelnytsk Region, Ukraine 4 Chernivtsi Regional Museum, 28, O. Kobylianska St., Chernivtsi 58002, Ukraine 5 National Nature Park “Bugsky Hard” 83, Pervomaiska St., Mygia 55223, Pervomaisky District, Mykolaiv Region, Ukraine 6 Vinnytsia Regional Laboratory Centre, 11, Malynovskyi St., Vinnytsya 21100, Ukraine Modern state of the wildcat populations in Ukraine is analyzed on the basis of de- tailed review and analysis of its records above (annotations) and before (detailed ca- dastre) 2000. Data on 71 modern records in 10 administrative regions of Ukraine are summarized, including: Lviv (8), Volyn (1), Ivano-Frankivsk (2), Chernivtsi (31), Khmelnyts kyi (4), Vinnytsia (14), Odesa (4), Mykolaiv (4), Kirovohrad (2) and Cherkasy (1) regions. Detailed maps of species distribution in some regions, and in Ukraine in gene ral, and the analysis of the rates of expansion as well as direction of change in species limits of the distribution are presented. Morphological characteristics of the samples from the territory of Ukraine are described. Keywords: wildcat, state of populations, geographic range, expansion, Ukraine.