The Ophicleide As an Orchestral Instrument: Past and Future Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Care & Maintenance

Care and Maintenance of the Euphonium and Piston-Valve Tuba You Will Need: 1) Soft cloth (cotton or flannel) 4) Valve brush 2) Flexible brush (also called a “snake”) 5) Tuning slide grease 3) Mouthpiece brush 6) Valve Oil Daily Care 1) Never leave your instrument unattended. It takes very little time for someone to take it. 2) The safest place for your instrument is in the case. Leave it there when you’re not playing. 3) Do not let other people use your instrument. They may not know how to hold and care for it. 4) Do not use your case as a chair, foot rest or step stool. It is not designed for that kind of weight. 5) Lay your case flat on the floor before opening it. Do not let it fall open. 6) Do not hit your mouthpiece, it can get stuck. 7) Do not lift your instrument by the valves. Use the bell and any large tubes on the outside edge. 8) No loose items in your case. Anything loose will damage your instrument or get stuck in it. 9) Do not put music in your case, unless space is provided for it. If you have to fold it or if it touches the instrument, it should NOT be there. 10) Avoid eating or drinking just before playing. If you do, rinse your mouth with water before playing. 11) You may not need to do it every day, but keep your valves running smooth with valve oil. Put the oil directly on the exposed valve, not in the holes on the bottom of the casings. -

A Lament for Sam Hughes the Last Great Ophicleidist by Trevor Herbert

A Lament for Sam Hughes The last great ophicleidist By Trevor Herbert On 1st April 1898, Sam Hughes died in a small terraced house at Three Mile Cross on the outskirts of Reading. His widow, in grief and poverty, petitioned the Royal Society of Musicians for a small grant to pay for his funeral. The Society, which had treated him kindly in the closing years of his life, responded benevolently once more, for it was known that his passing marked the end of a significant, if brief, era. Sam Hughes was the last great ophicleide player. He was perhaps the only really great British ophicleide player. Many great romantic composers including Mendelssohn, Wagner and Berlioz wrote for the instrument, which was invented by a man called Halary in Paris in 1821 - three years before Sam Hughes was born. For the next half century it was widely used but few played it well. George Bernard Shaw regularly referred to it as the "chromatic bullock" but even he, whose caustic indignation was often vented on London's brass players, had been moved by a rendering of O Ruddier than the Cherry by Mr Hughes. The fate of the ophicleide and the story of Sam Hughes provide a neat illustration of the pace and character of musical change in Britain in the Victorian period. One product of this change was the brass band "movement" - a movement which, if the untested claims of most authors on the subject are to be believed, had its origins in Wales. Despite Shaw's claims that the ophicleide had been "born obsolete", it died because it was consumed by the irresistible forces of technological invention and commercial exploitation. -

The Sackbut and Pre-Reformation English Church Music

146 HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL THE SACKBUT AND PRE-REFORMATION ENGLISH CHURCH MUSIC Trevor Herbert n the mid-1530s the household account books of the Royal Court in London showed that as many as twelve trombone players were in receipt of regular fees. If these accounts /signify all expenditure on Court music at that time, it can be estimated that an eighth of the wages bill for this part of its activities went to trombone players. The 1530s were something of a high point in this respect, but it remains the case that for the whole of the 16th century a corps of trombonists were, in effect, salaried members of the royal musical establishment.1 Yet, not a single piece of English music from this period is explicitly linked to the trombone. This in itselfis not significant, as the labelling of parts at this time was rare,2 but the illustration draws historians of brass instruments to a neat focus. Throughout the 16th century trombonists occupied a regular and important place in English musical life. The players were professionals, probably fine and distinguished performers: What did they play and when did they play it? In this article I address some issues concerning the deployment of trombones in the first half of the 16th century. It is worth stressing that musical practice in England in the 16th century was sufficiently different from the rest of Europe to merit special attention. As I explain below, the accession of Henry VII marks what many historians recognize as a watershed in British history. The death of his son Henry VIII in 1547 marks another. -

Tutti Brassi

Tutti Brassi A brief description of different ways of sounding brass instruments Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2018 The author’s moral rights have been asserted Hataf Segol Publications 2018 Typeset in XƎLATEX by Simon Montagu Why Mouthpieces 1 Cornets and Bugles 16 Long Trumpets 19 Playing the Handhorn in the French Tradition 26 The Mysteries of Fingerhole Horns 29 Horn Chords and Other Tricks 34 Throat or Overtone Singing 38 iii This began as a dinner conversation with Mark Smith of the Ori- ental Institute here, in connexion with the Tutankhamun trum- pets, and progressed from why these did not have mouthpieces to ‘When were mouthpieces introduced?’, to which, on reflection, the only answer seemed to be ‘Often’, for from the Danish lurs onwards, some trumpets or horns had them and some did not, in so many cultures. But indeed, ‘Why mouthpieces?’ There seem to be two main answers: one to enable the lips to access a tube too narrow for the lips to access unaided, and the other depends on what the trumpeter’s expectations are for the instrument to achieve. In our own culture, from the late Renaissance and Early Baroque onwards, trumpeters expected a great deal, as we can see in Bendinelli’s and Fantini’s tutors, both of which are avail- able in facsimile, and in the concert repertoire from Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo onwards. As a result, mouthpieces were already large, both wide enough and deep enough to allow the player to bend the 11th and 13th partials and other notes easily. The transition from the base of the cup into the backbore was a sharp edge. -

Douglas Yeo: Historical Instruments Vitae

Douglas Yeo Serpent ~ Ophicleide ~ Buccin ~ Bass Sackbut Historical Instruments Vitae Primary Positions • Professor of Trombone, Arizona State University (2012 – ) • Bass Trombonist, Boston Symphony Orchestra (1985 – 2012) • Faculty, New England Conservatory of Music (1985 – 2012) Historical Instruments Used • Church serpent in C by Baudouin, Paris (c. 1812). Pearwood, 2 keys. • Church serpent in C by Keith Rogers, Christopher Monk Instruments, Greenwich (1996). Walnut, 1 key. • Church serpent in C by Keith Rogers, Christopher Monk Instruments, Forest Hills (1998). Plum wood, python skin, 2 keys. • Church serpent in D by Christopher Monk. Sycamore. • English military serpent in C by Keith Rogers, Christopher Monk Instruments, Yaxham (2007). Sycamore, 3 keys. • Ophicleide in C by Roehn, Paris (c. 1855). 9 keys. • Buccin in B flat by Sautermeister, Lyon (c. 1830); modern hand slide after historical models by James Becker (2005) • Bass sackbut in F by Frank Tomes, London (2000). Performances with Early Instrument Orchestras 2001 Bass sackbut. Monteverdi: “L’Orfeo” (Boston Baroque) 2001 Serpent. Handel: “Music for the Royal Fireworks” (Boston Baroque) 2002 Ophicleide. Berlioz: “Symphonie Fantastique” (Handel & Haydn Society) 2002 Bass sackbut. Monteverdi: “Vespers of 1610” (Handel & Haydn Society) 2005 Ophicleide. Berlioz: “Romeo et Juliette” (Chorus Pro Musica) 2005 Serpent. Purcell: “Dido and Aeneas” (Handel & Haydn Society) 2006 Bass sackbut. Monteverdi: “L’Orfeo” (Handel & Haydn Society) 2006 Serpent and Ophicleide: Berlioz: “Symphonie Fantastique” (Handel & Haydn Society) 2008 Serpent. Handel: “Music for the Royal Fireworks” (Handel & Haydn Society) 2009 Ophicleide. Mendelssohn: Incidental music to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (Philharmonia Baroque, San Francisco, CA) 1 Performances with Modern Instrument Orchestras 1994 Serpent. Berlioz: “Messe solennelle” (Boston Symphony Orchestra – Ozawa) 1998 Serpent. -

Journal of the Conductors Guild

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 2015-2016 19350 Magnolia Grove Square, #301 Leesburg, VA 20176 Phone: (646) 335-2032 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.conductorsguild.org Jan Wilson, Executive Director Officers John Farrer, President John Gordon Ross, Treasurer Erin Freeman, Vice-President David Leibowitz, Secretary Christopher Blair, President-Elect Gordon Johnson, Past President Board of Directors Ira Abrams Brian Dowdy Jon C. Mitchell Marc-André Bougie Thomas Gamboa Philip Morehead Wesley J. Broadnax Silas Nathaniel Huff Kevin Purcell Jonathan Caldwell David Itkin Dominique Royem Rubén Capriles John Koshak Markand Thakar Mark Crim Paul Manz Emily Threinen John Devlin Jeffery Meyer Julius Williams Advisory Council James Allen Anderson Adrian Gnam Larry Newland Pierre Boulez (in memoriam) Michael Griffith Harlan D. Parker Emily Freeman Brown Samuel Jones Donald Portnoy Michael Charry Tonu Kalam Barbara Schubert Sandra Dackow Wes Kenney Gunther Schuller (in memoriam) Harold Farberman Daniel Lewis Leonard Slatkin Max Rudolf Award Winners Herbert Blomstedt Gustav Meier Jonathan Sternberg David M. Epstein Otto-Werner Mueller Paul Vermel Donald Hunsberger Helmuth Rilling Daniel Lewis Gunther Schuller Thelma A. Robinson Award Winners Beatrice Jona Affron Carolyn Kuan Jamie Reeves Eric Bell Katherine Kilburn Laura Rexroth Miriam Burns Matilda Hofman Annunziata Tomaro Kevin Geraldi Octavio Más-Arocas Steven Martyn Zike Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado Frederick Fennell Robert Shaw Maurice Abravanel Bernard Haitink Leonard Slatkin Marin Alsop Margaret Hillis Esa-Pekka Salonen Leon Barzin James Levine Sir Georg Solti Leonard Bernstein Kurt Masur Michael Tilson Thomas Pierre Boulez Sir Simon Rattle David Zinman Sir Colin Davis Max Rudolf Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 (2015-2016) Nathaniel F. -

Dr. Davidson's Recommendations for Trombones

Dr. Davidson’s Recommendations for Trombones, Mouthpieces, and Accessories Disclaimer - I’m not under contract with any instrument manufacturers discussed below. I play an M&W 322 or a Greenhoe Optimized Bach 42BG for my tenor work, and a Courtois 131R alto trombone. I think the M&W and Greenhoe trombones are the best instruments for me. Disclaimer aside, here are some possible recommendations for you. Large Bore Tenors (.547 bore) • Bach 42BO: This is an open-wrap F-attachment horn. I’d get the extra light slide, which I believe is a bit more durable, and, if possible, a gold brass bell. The Bach 42B was and is “the gold standard.” Read more here: http://www.conn-selmer.com/en-us/our-instruments/band- instruments/trombones/42bo/ • M&W Custom Trombones: Two former Greenhoe craftsman/professional trombonists formed their own company after Gary Greenhoe retired and closed his store. The M&W Trombones are amazing works of art, and are arguably the finest trombones made. The 322 or 322-T (T is for “Tuning-in Slide”) models are the tenor designations. I’m really a fan of one of the craftsman, Mike McLemore – he’s as good as they come. Consider this. These horns will be in-line, price-wise, with the Greenhoe/Edwards/Shires horns – they’re custom made, and will take a while to make and for you to receive them. That said, they’re VERY well-made. www.customtrombones.com • Yamaha 882OR: The “R” in the model number is important here – this is the instrument designed by Larry Zalkind, professor at Eastman, and former principal trombonist of the Utah Symphony. -

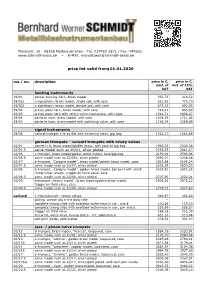

Price List Valid From: 01.01.2020

Mosenstr. 10 - 08258 Markneukirchen - Tel. 037422 2871 / Fax -749631 www.schmidt-brass.de - E-Mail: [email protected] price list valid from: 01.01.2020 mo./ no. description price in €, price in €, excl. of incl. of 19% VAT VAT hunting instruments 19/01 pocket hunting-horn, brass model 351,72 418,52 19/021 c-signalhorn, brass model, single coil, with case 651,92 775,73 19/022 c-signalhorn, brass model, double coil, with case 674,33 802,39 19/02 prince pless horn, brass model, with case 716,91 853,06 19/03 prince pless horn with rotary valve mechanism, with case 1544,71 1838,07 19/04 parforce horn, brass model, with case 1438,29 1711,44 19/05 parforce horn, brass model with switching valve, with case 1756,34 2089,89 signal instruments 19/08 natural trumpet in b-es flat with switching valve, gig bag 1062,17 1263,89 german trumpets – concert trumpets with rotary valves 20/01 cornet in b, brass model/golden brass, with case or gig bag 1965,35 2338,56 20/01 S same model such as 20/01, silver plated 2236,53 2661,27 20/05 c-trumpet, brass model/golden brass model, case/gig-bag 2159,04 2569,06 20/05 S same model such as 20/051, silver plated 2696,07 3208,08 20/07 b-trumpet, “Cologne model”, brass model/golden brass model, case 1923,88 2289,24 20/07 S same model such as 20/07, silver plated 2202,29 2620,53 20/08 b-trumpet, „Cologne model”, golden brass model, bell joint with small 2429,81 2891,25 nickel silver wreath, trigger on third valve, case 20/08 S same model such as 20/08, silver plated 2707,95 3222,21 20/09 b-trumpet „Heckel model“, brass model/golden brass model, 2501,22 2976,22 trigger on third valve, case 20/09 S same model such as 20/09, silver plated 2779,73 3307,63 optional J. -

Mouthpiece Catalog

14 A CUP DIAMETER RIM CONTOUR CUP VOLUME 4 a BACKBORE Model mm inches Description A small cup diameter with shallow “A” cup 5A4 15.84 .624 and semi-flat rim offers comfort and resistance in the upper register. A shallow “A” cup with cushion #4 rim for 6A4a 15.99 .630 extreme high register work. Excellent for the player with thin lips. A #4 rim 7B4 16.08 .633 provides good endurance with a brilliant tone. The slightly funnel-shaped cup at the entrance 8A4 16.25 .640 to the throat provides a good tone and the #4 semi-flat rim gives superior endurance. The deep funnel-shaped cup provides 8E2 16.15 .636 a smooth tone and is very flexible in all registers. Recommended for cornet players. Standard characteristics allow for a full 9 16.33 .643 penetrating tone quality. Like the 9, however the #4 semi-flat rim 9C4 16.36 .644 provides excellent endurance. The combination of the shallow “A” cup, semi- 10A4a 16.43 .647 flat #4 rim and tight “a” backbore assists with upper register work. Same as the 10A4a but with a standard “c” 10A4 16.43 .647 backbore, which offers less resistance. A medium-small funnel-shaped “B” cup offers 10B4 16.43 .647 both a quality sound and support in the upper register. This rim size and contour is similar to the 11 11A 16.51 .650 but with a shallower “A” cup. This model was developed for the Schilke piccolo trumpets. The “x” backbore improves the 11Ax 16.51 .650 ease of playing and opens up the sound on the piccolo.