After Yellow Ribbons: Providing Veteran-Centered Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lawyer in Society" Will Be Published by Texasbarbooks in February 2012

IN THE ARENA: THEODORE ROOSEVELT AND THE LAW TALMAGE BOSTON, Shareholder Winstead PC 1201 Elm Street 5400 Renaissance Tower Dallas, Texas 75270 (214) 745-5462 (Direct) [email protected] State Bar of Texas 28TH ANNUAL LITIGATION UPDATE INSTITUTE January 19-20, 2012 Dallas CHAPTER 21 Talmage Boston is a shareholder in the Dallas office of Winstead PC. He is a past Director of the SBOT, and has served as Chairman of the SBOT's Litigation Section, its Council of Chairs, and its Annual Meeting Committee. He has been the recipient of the SBOT's Presidential Citation every year from 2005-2011. Talmage practices in the area of commercial litigation, and is certified (and has been recertified many times) in both Civil Trial Law and Civil Appellate Law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization. He currently serves on the editorial board of the Texas Bar Journal, and In the last 3 years, has written 3 featured articles in the Texas Bar Journal on Abraham Lincoln, Atticus Finch, and Theodore Roosevelt. His book "Raising the Bar; The Crucial Role of the Lawyer in Society" will be published by TexasBarBooks in February 2012. In the Arena: Theodore Roosevelt and the Law Chapter 21 TABLE OF CONTENTS INSPIRATION .................................................................................................................................................................................1 ROOSEVELT AND THE LAW .......................................................................................................................................................1 -

Nominations Before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Second Session, 109Th Congress

S. HRG. 109–928 NOMINATIONS BEFORE THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE, SECOND SESSION, 109TH CONGRESS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF HON. PRESTON M. GEREN; HON. MICHAEL L. DOMINGUEZ; JAMES I. FINLEY; THOMAS P. D’AGOSTINO; CHARLES E. McQUEARY; ANITA K. BLAIR; BENEDICT S. COHEN; FRANK R. JIMENEZ; DAVID H. LAUFMAN; SUE C. PAYTON; WILLIAM H. TOBEY; ROBERT L. WILKIE; LT. GEN. JAMES T. CONWAY, USMC; GEN BANTZ J. CRADDOCK, USA; VADM JAMES G. STAVRIDIS, USN; NELSON M. FORD; RONALD J. JAMES; SCOTT W. STUCKY; MARGARET A. RYAN; AND ROBERT M. GATES FEBRUARY 15; JULY 18, 27; SEPTEMBER 19; DECEMBER 4, 5, 2006 Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services ( VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:22 Jun 28, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 36311.TXT SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 NOMINATIONS BEFORE THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE, SECOND SESSION, 109TH CONGRESS VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:22 Jun 28, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 36311.TXT SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 S. HRG. 109–928 NOMINATIONS BEFORE THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE, SECOND SESSION, 109TH CONGRESS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF HON. PRESTON M. GEREN; HON. MICHAEL L. DOMINGUEZ; JAMES I. FINLEY; THOMAS P. D’AGOSTINO; CHARLES E. McQUEARY; ANITA K. BLAIR; BENEDICT S. COHEN; FRANK R. JIMENEZ; DAVID H. LAUFMAN; SUE C. PAYTON; WILLIAM H. TOBEY; ROBERT L. WILKIE; LT. GEN. -

MEETING of the FULL BOARD Friday, June 4, 2021 1:15 – 3:00

MEETING OF THE FULL BOARD Friday, June 4, 2021 1:15 – 3:00 p.m. Pavilion Ballroom, Boar’s Head Resort PAGE A. Approval of the Minutes of the March 3-5, 2021 Regular Meeting, April 13, 2021, and May 17, 2021 Special Meetings of the Board of Visitors (The Rector) 1 B. Consent Agenda Items (The Rector) 1. Resolution to Approve Additional Agenda Items 1 2. Assignment of Pavilion VI 1 3. Assignment of Montebello 1 4. Miller Center Governing Council Appointments 1 5. Reappointment of William G. Crutchfield Jr. to the Health System Board 3 6. Appointment of Kenneth Botsford, M.D. to the Health System Board 3 C. Action Items 1. Memorial Resolution for Robert G. Butcher Jr. 3 2. Memorial Resolution for Thomas F. Farrell II 4 3. Commending Resolution for John A. Griffin 6 4. Commending Resolution for Ellen M. Bassett 7 D. Leadership Discussion 1. ACTION ITEM: Free Speech Principles 8 2. Strategic Plan Progress 3. Thomas Jefferson Awards E. Remarks/Reports: 1. Remarks by the Rector 2. Remarks by the Student Member (Ms. Sarita Mehta) 3. Remarks by the Faculty Senate Chair (Mr. Joel Hockensmith) 4. Gifts and Grants Report (Written Report) 12 A. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES OF THE MARCH 3-5, 2021 REGULAR MEETING, APRIL 13, 2021 AND MAY 17, 2021 ELECTRONIC MEETINGS OF THE BOARD OF VISITORS RESOLVED, the Board of Visitors approves the minutes of the March 3-5, 2021 Regular Meeting, April 13, 2021 and May 17, 2021 Electronic Meetings of the Board of Visitors. # # # B.1. RESOLUTION TO APPROVE ADDITIONAL AGENDA ITEMS RESOLVED, the Board of Visitors approves the consideration of addenda to the published Agenda. -

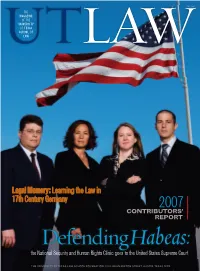

Fall 2007 Issue of UT Law Magazine

FALL 2007 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SCHOOL OF UTLAW LAW 2007 CONTRIBUTORS’ REPORT Defending Habeas: the Nationalational Security and Human Rights CCliniclinic ggoesoes ttoo tthehe United States SuSupremepreme CCourtourt THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS LAW SCHOOL FOUNDATION, 727 E. DEAN KEETON STREET, AUSTIN, TEXAS 78705 UTLawCover1_FIN.indd 2 11/14/07 8:07:37 PM 22 UTLAW Fall 2007 UTLaw01_FINAL.indd 22 11/14/07 7:46:29 PM InCamera Immigration Clinic works for families detained in Taylor, Texas The T. Don Hutto Family Residential Facility in Taylor, Texas currently detains more than one hundred immigrant families at the behest of the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. The facility, a former medium security prison, is the subject of considerable controversy regarding the way detainees are treated. For the past year, UT Law’s Immigration Clinic has worked to improve the conditions at Hutto. In this photograph, (left to right) Farheen Jan,’08, Elise Harriger,’08, Immigration Clinic Director and Clinical Professor Barbara Hines, Matt Pizzo,’08, Clinic Administrator Eduardo A Maraboto, and Kate Lincoln-Goldfi nch, ’08, stand outside the Hutto facility. Full story on page 16. Photo: Christina S. Murrey FallFall 2007 2007 UT UTLAWLAW 23 1 UTLaw01_FINAL.indd 23 11/14/07 7:46:50 PM 6 16 10 4 Home to Texas 10 Legal Memory: 16 Litigation, Activism, In the Class of 2010—students who Learning the Law in and Advocacy: entered the Law School in fall 2007— thirty-eight percent are Texas residents 17th-Century Germany Immigration Clinic works who left the state for their undergradu- ate educations and then returned for One of the remarkable books in the for detained families law school. -

Bloch Rubin ! ! a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of The

! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making. And, in tracing the development of intraparty organization through several well-known examples of party infighting, I will demonstrate that intraparty organizations have played pivotal — yet largely unrecognized — roles in critical legislative battles, including turn-of-the-century economic struggles, midcentury battles over civil rights legislation, and contemporary debates over national health care policy. -

![[Publish] in the United States](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5861/publish-in-the-united-states-2785861.webp)

[Publish] in the United States

[PUBLISH] IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT FILED ________________________ U.S. COURT OF APPEALS ELEVENTH CIRCUIT No. 09-14657 JUNE 28, 2011 JOHN LEY ________________________ CLERK D. C. Docket No. 07-00001 MD-J-PAM-JRK In Re: MDL-1824 TRI-STATE WATER RIGHTS LITIGATION ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3:07-cv-00249 STATE OF ALABAMA, ALABAMA POWER COMPANY, STATE OF FLORIDA, Plaintiffs-Appellees, versus UNITED STATES ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS, JOHN M. McHUGH, Secretary of the Army, et al., Defendants-Appellees Cross-Appellants. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3:07-cv-00252 STATE OF GEORGIA, GWINNETT COUNTY, GEORGIA, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants Cross-Appellees, versus UNITED STATES ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS, JOHN M. McHUGH, in his official capacity as Secretary of the United States Army, et al., Defendants-Appellees Cross-Appellants. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3:08-cv-233 CITY OF APALACHICOLA, FLORIDA, Plaintiff-Appellee, versus UNITED STATES ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS, JOHN M. McHUGH, Secretary of the Army, et al., Defendants-Appellees Cross-Appellants ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3:08-cv-640 SOUTHEAST FEDERAL POWER CUSTOMERS, INC., CITY OF APALACHICOLA, FLORIDA, Plaintiffs-Appellees, versus UNITED STATES ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS, JOHN -

AFA National Convention 2005

Air Force Association National Convention 2005 Delegates at the 2005 AFA National Convention gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to participate in a memorial service honoring AFA members who died during the previous year and to observe a wreath-laying ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknowns. Below, AFA’s Chairman of the Board Stephen P. “Pat” Condon (left) and National President Robert E. “Bob” Largent salute as a bugler plays Taps. Photos by Guy Aceto and Joe Orlando 7676 AIR FORCE Magazine // NovemberNovember 20052005 Air Force Association National Convention 2005 By Tamar A. Mehuron, Associate Editor HE entire Class of 2006 from USAF’s Air Command and Staff College, Maxwell AFB, Ala., attended the Air Force Association’s Air & Space Conference and Technology Exposition, held in mid-September at the Marriott Wardman Park Hotel in Washington, D.C. It was the first-ever Tventure of its type for ACSC. The class of some 570 airmen, accompanied by faculty members, arrived Sunday, Sept. 11, and stayed through Wednesday, Sept. 14. The students’ attendance was made possible by a grant from Boeing Co. and AFA. Their presence meant these future Air Force leaders got to know AFA, meet and talk with current USAF leaders, and acquaint themselves with defense and aerospace industry representatives, including executives. The students also at- tended a wide variety of Air & Space Conference panels and seminars and AIRAIR FORCEFORCE MagazineMagazine // NovemberNovember 20052005 7777 visited the Aerospace Technology Exposition’s samplings of advanced technology developments. The students were joined by more than 6,300 attendees registered for the Air & Space Conference, along with hundreds of AFA members and delegates who gathered Saturday, Sept. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, JANUARY 13, 1995 No. 8 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The message also announced that the f A message from the Senate by Mr. Chair announces the following two ap- Hallen, one of its clerks, announced pointments made by the Democratic PRAYER that the Senate had passed with an leader, Mr. Mitchell, during the sine die adjournment: The Chaplain, Rev. James David amendment in which the concurrence Pursuant to Public Law 103±236, the Ford, D.D., offered the following pray- of the House is requested, a bill of the er: House of the following title: appointment of Mr. MOYNIHAN and Samuel P. Huntington of New York, as During these days when our memo- H.R. 1. An act to make certain laws appli- members of the Commission on Pro- ries are filled with the life and work of cable to the legislative branch of the Federal Martin Luther King, Jr., we recall, O Government. tecting and Reducing Government Se- crecy. God, the works of justice that he did The message also announced that the Pursuant to section 114(b)(1) of Pub- and inspired others to do and we re- Senate had passed a bill of the follow- lic Law 100±458, the reappointment of dedicate ourselves to what we should ing title, in which the concurrence of be and to the good works that we can William Winter to a 6-year term on the the House is requested: Board of Trustees of the John C. -

H. Doc. 108-222

ONE HUNDRED SECOND CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1991 TO JANUARY 3, 1993 FIRST SESSION—January 3, 1991, to January 3, 1992 SECOND SESSION—January 3, 1992, to October 9, 1992 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—J. DANFORTH QUAYLE, of Indiana PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ROBERT C. BYRD, of West Virginia SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—WALTER J. STEWART, of Washington, D.C. SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MARTHA S. POPE, 1 of Connecticut SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—THOMAS S. FOLEY, 2 of Washington CLERK OF THE HOUSE—DONNALD K. ANDERSON, 2 of California SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JACK RUSS, 3 of Maryland; WERNER W. BRANDT, 4 of New York DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JAMES T. MALLOY, 2 of New York POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—ROBERT V. ROTA, 2 of Pennsylvania DIRECTOR OF NON-LEGISLATIVE AND FINANCIAL SERVICES 5—LEONARD P. WISHART III, 6 of New Jersey ALABAMA John S. McCain III, Phoenix Pete Wilson, 9 San Diego 10 SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John Seymour, Anaheim Dianne Feinstein, 11 San Francisco Howell T. Heflin, Tescumbia John J. Rhodes III, Mesa Richard C. Shelby, Tuscaloosa Morris K. Udall, 7 Tucson REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Ed Pastor, 8 Phoenix Frank Riggs, Santa Rosa Wally Herger, Rio Oso Sonny Callahan, Mobile Bob Stump, Tolleson William L. Dickinson, Montgomery Jon Kyl, Phoenix Robert T. Matsui, Sacramento Glen Browder, Jacksonville Jim Kolbe, Tucson Vic Fazio, West Sacramento Tom Bevill, Jasper Nancy Pelosi, San Francisco Bud Cramer, Huntsville ARKANSAS Barbara Boxer, Greenbrae George Miller, Martinez Ben Erdreich, Birmingham SENATORS Claude Harris, Tuscaloosa Ronald V. Dellums, Oakland Dale Bumpers, Charleston Fortney Pete Stark, Oakland ALASKA David H. -

Nattrass How 08-06-2010

Tilburg University How are we to go on together? Dialogues on the social construction of sustainability Altomare Nattrass, M.E. Publication date: 2010 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Altomare Nattrass, M. E. (2010). How are we to go on together? Dialogues on the social construction of sustainability. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. sep. 2021 HOW ARE WE TO GO ON TOGETHER? DIALOGUES ON THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF SUSTAINABILITY Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Tilburg op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Ruth First zaal van de Universiteit op dinsdag 8 juni 2010 om 14.15 uur door Mary Elizabeth Altomare Nattrass, geboren op 8 maart 1950 te Concord, New Hampshire, USA. -

TCU DAILY SKIFF Vol

TCU DAILY SKIFF Vol. 87, No. 22 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 9, 1986 Fort Worth, Texas Forum will host opposing views By Kevin Marks House is insuring a fair presentation of positions opposed to apartheid." Staff Writer Another bill introduced during last This week was productive for the week's House meeting made it back to Student House of Representatives, as the floor Tuesday. A bill to support members pushed through various government publications was passed pieces of legislation during the meet- with less controversy than the apar- ing Tuesday afternoon. theid lectures bill. The House Finance Committee The House voted to allocate $979 approved a bill to allocate $500 to in- from the Special Projects Fund to vite a member of the African National send the co-editors-in-chief and spon- Congress to speak at an upcoming sor of the yearbook to the Associated TCU forum featuring Helen Suzman. College Press National Convention in Suzman is a member of the South Washington, DC. According to the African Parliament. bill's author, the bill will provide the Steve Partain, a town representa- opportunity to learn important skills tive, asked that the House attach an and practices necessary to the year- amendment to the bill requesting that book staff, the Forums Committee be consulted In other House action, a bill to concerning the format of the Helen establish student recognition of Suzman lecture. teaching excellence was introduced to "Forums wants to insure a profes- members before being sent to the sional and non-hostile atmosphere Elections and Regulations Com- mittee. with both presentations," Partain said. -

Honoring the Victims of the June 25, 1996, Terrorist Bombing in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia R E P O R T Committee on National Security

1 104TH CONGRESS REPORT 2nd Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 104±805 "! HONORING THE VICTIMS OF THE JUNE 25, 1996, TERRORIST BOMBING IN DHAHRAN, SAUDI ARABIA R E P O R T OF THE COMMITTEE ON NATIONAL SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON H. CON. RES. 200 [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] SEPTEMBER 17, 1996.ÐOrdered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 29±006 WASHINGTON : 1996 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON NATIONAL SECURITY ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS FLOYD D. SPENCE, South Carolina, Chairman BOB STUMP, Arizona RONALD V. DELLUMS, California DUNCAN HUNTER, California G.V. (SONNY) MONTGOMERY, Mississippi JOHN R. KASICH, Ohio PATRICIA SCHROEDER, Colorado HERBERT H. BATEMAN, Virginia IKE SKELTON, Missouri JAMES V. HANSEN, Utah NORMAN SISISKY, Virginia CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania JOHN M. SPRATT, JR., South Carolina ROBERT K. DORNAN, California SOLOMON P. ORTIZ, Texas JOEL HEFLEY, Colorado OWEN PICKETT, Virginia JIM SAXTON, New Jersey LANE EVANS, Illinois RANDY ``DUKE'' CUNNINGHAM, California JOHN TANNER, Tennessee STEVE BUYER, Indiana GLEN BROWDER, Alabama PETER G. TORKILDSEN, Massachusetts GENE TAYLOR, Mississippi TILLIE K. FOWLER, Florida NEIL ABERCROMBIE, Hawaii JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York CHET EDWARDS, Texas JAMES TALENT, Missouri FRANK TEJEDA, Texas TERRY EVERETT, Alabama MARTIN T. MEEHAN, Massachusetts ROSCOE G. BARTLETT, Maryland ROBERT A. UNDERWOOD, Guam HOWARD ``BUCK'' MCKEON, California JANE HARMAN, California RON LEWIS, Kentucky PAUL MCHALE, Pennsylvania J.C. WATTS, JR., Oklahoma PETE GEREN, Texas MAC THORNBERRY, Texas PETE PETERSON, Florida JOHN N. HOSTETTLER, Indiana WILLIAM J. JEFFERSON, Louisiana SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia ROSA L. DELAURO, Connecticut VAN HILLEARY, Tennessee MIKE WARD, Kentucky JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida PATRICK J. KENNEDY, Rhode Island WALTER B.